Epidemiological studies show that methamphetamine use has increased to the point that it is now a major national public health concern.

1 The increased prevalence and legal and social consequences of this problem have been well documented; however, other possible consequences, such as the neurocognitive impairment, have been largely neglected. A rich preclinical literature using animal models of methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity suggests that neurocognitive consequences can be expected in human subjects. Early studies showed that relatively large doses of methamphetamine produced marked neurophysiological changes, such as altered striatal dopamine function, which were evident even three to four years later.

2–5 Recent studies using relatively small doses over shorter periods have reported persistent changes in dopaminergic functioning

6–8 and deficits on measures of working memory.

9In studies of human subjects, the psychiatric

10–12 and neurological

13,14 consequences of methamphetamine use have received attention in the literature; in contrast, limited data are available on whether methamphetamine dependence is a risk factor for neurocognitive impairment. One recent study demonstrated that methamphetamine dependence is associated with memory deficits and motor slowing in individuals who were abstinent for up to one year.

15 Another study suggested that methamphetamine-dependent subjects resembled patients with frontal lobe damage in their performance on a novel test of decision making.

16 Although the study was informative, it used a single neurocognitive measure. Another study recruited an unusually young sample of methamphetamine-dependent individuals (mean age, 19 years) and used a battery that was relatively insensitive to frontal, temporal, and subcortical impairments.

17Hence, key questions remain unanswered, including the effects of methamphetamine dependence across neurocognitive domains. The purpose of this study was to determine whether methamphetamine dependence is associated with neurocognitive impairment across a range of measures in users whose abstinence was continuously monitored.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows that the methamphetamine-dependent individuals and the non-drug-using control subjects did not differ in terms of age, education, estimated level of premorbid intellectual functioning, or severity of self-reported depressive symptomatology. Therefore, covariates were not included in subsequent group comparisons.

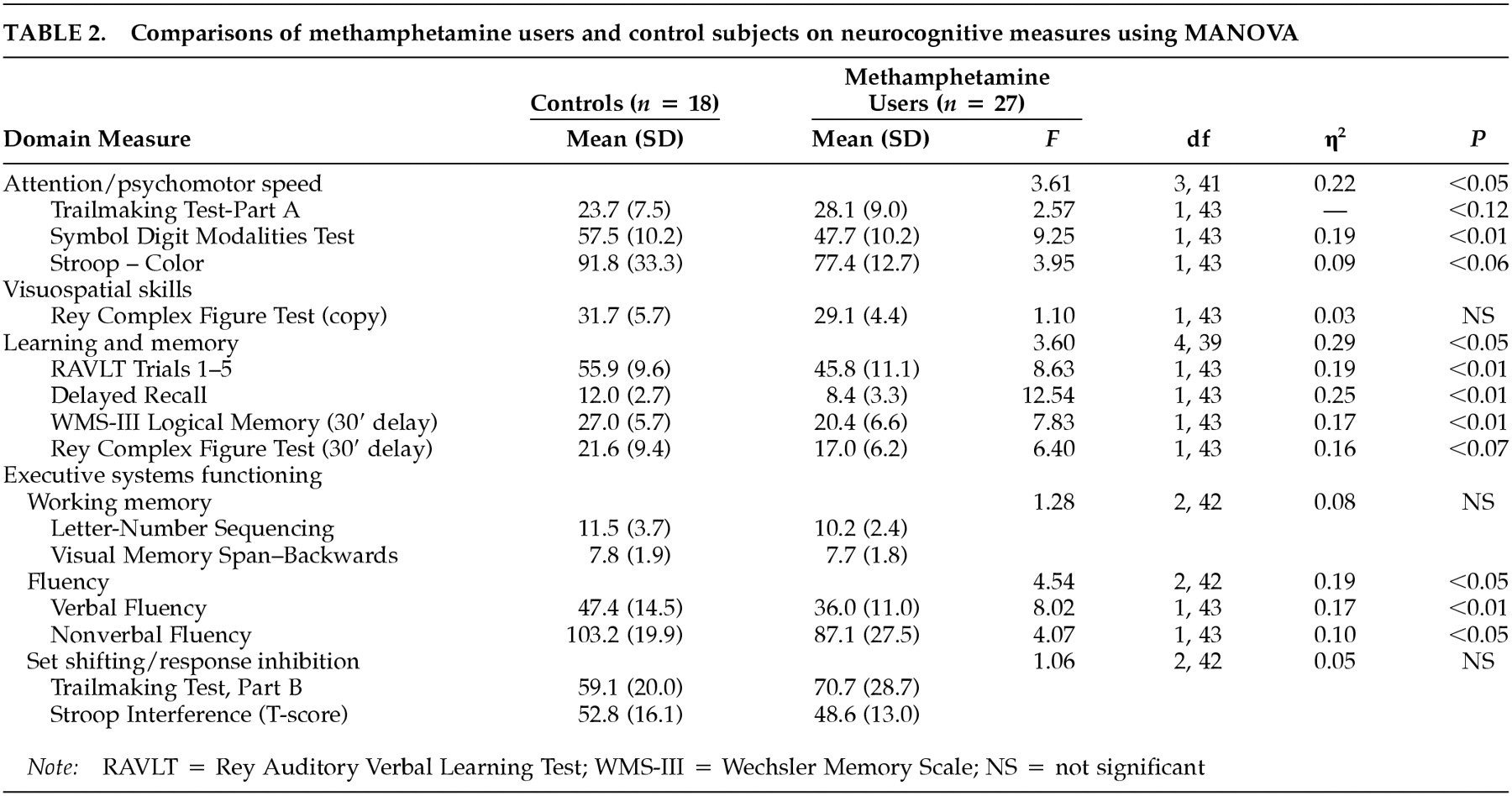

Table 2 reveals that methamphetamine users showed significantly poorer performance than control subjects on measures of attention/psychomotor speed, on measures of verbal learning and memory, and on fluency-based measures of executive systems functioning (i.e., fluency, set shifting/inhibition). On a measure of nonverbal learning and memory, a trend was observed indicating that methamphetamine-dependent individuals performed poorly relative to non-drug-using controls. The groups did not differ on a measure of visuospatial skills, untimed tests of working memory, or measures of set shifting/response inhibition. The magnitudes of the significant associations ranged from moderate (η

2>0.19) to large (η

2>0.29).

Table 2 also shows consistency in the effects across the neurocognitive tests that constituted each domain.

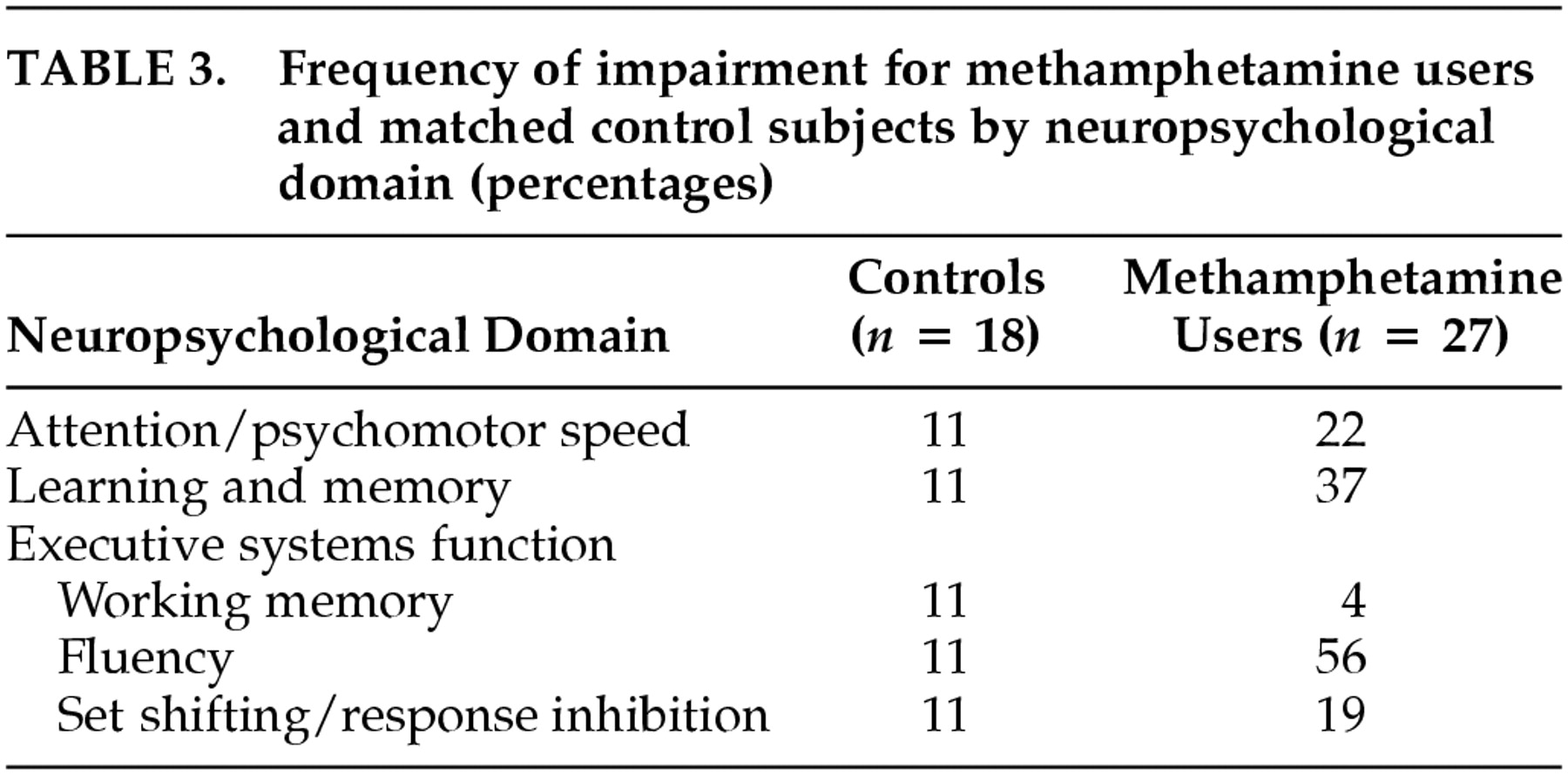

A separate set of analyses determined whether the groups differed in the number of individuals who would be classified as impaired. Participants were considered to be impaired within a particular neurocognitive domain if their score was at least two standard deviations below the mean (according to published norms) on at least one test. For each test, this determination was based on scores adjusted for age, education, and gender. Miller and colleagues have used a similar algorithm.

30Table 3 lists the percentage of individuals in each group who met criteria for impairment in each neurocognitive domain. Although the groups did not differ on untimed measures of working memory or set shifting/response inhibition, moderate group differences in classification rates of impairment were observed on measures of attention/psychomotor speed and learning and memory. Methamphetamine-dependent individuals were much more likely than non-drug-users to be classified as impaired on measures of fluency.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, these findings are the first to demonstrate that methamphetamine dependence is associated with impairments across a range of neurocognitive domains, including attention/psychomotor speed, learning and memory, and fluency-based measures of executive systems functioning, in a sample of users whose abstinence was monitored with urine screening. Moreover, methamphetamine-dependent individuals were more likely than non-drug-users to be classified as impaired in the areas of attention/psychomotor speed, learning and memory, and executive systems functioning. Furthermore, the differential performance across the test and control groups was not attributable to demographic profile, estimated premorbid IQ, and level of self-reported depression.

The degree of impairment in this sample of methamphetamine users is substantial, and it is greater than has been observed in neurocognitive studies of cocaine dependence

31,32 and even alcohol dependence (without Korsakoff's syndrome).

33 Because this study used a cross-sectional design, however, causality cannot be inferred. It is also possible that a single factor that we did not measure produced a liability to develop methamphetamine dependence and neurocognitive impairment.

34Although it is possible that the observed neurocognitive deficits were the result of a transient “crash” phase or the residual symptoms of withdrawal, we used a number of precautions to reduce the likelihood that such factors would affect test performance. For example, urine screening was used to monitor abstinence from drug use. Furthermore, methamphetamine-dependent study participants reported only minimal levels of dysphoric mood, agitation, insomnia, or slowness of movement—the cardinal symptoms of stimulant withdrawal—on the day on which the neurocognitive measures were administered. The latter finding is consistent with a recently published report showing that symptoms of methamphetamine withdrawal resolve to minimal levels by the 5th day of abstinence.

19It is important to note that no controlled studies have documented the time course of methamphetamine withdrawal in human subjects. Although we considered a host of factors that potentially moderate performance on neurocognitive tests, preclinical research has shown that the dopaminergic system is affected for months after cessation of methamphetamine use.

6,7 Therefore, undetected factors related to withdrawal might have affected test performance for this sample. Conversely, in a sample of 15 detoxified methamphetamine-dependent individuals, Volkow and colleagues reported that methamphetamine-dependent individuals demonstrate poor test performance even after 12 months of abstinence.

15 Their work suggests that the impairments observed during the early phases of abstinence are relatively stable.

While these findings preliminarily show that methamphetamine dependence is associated with neurocognitive impairment, several limitations should be noted. The sample size was not large enough to identify risk factors or protective factors that might distinguish between impaired and nonimpaired methamphetamine-dependent subjects. Likely factors that should be considered in future studies include the amount, frequency, and duration of use of methamphetamine, and demographic factors, such as age, education, and socioeconomic status. The sample size also limits the degree to which these findings are generalizable to methamphetamine-dependent individuals with different demographic and drug use profiles. The period of abstinence for our study subjects, 5 to 14 days, constitutes another potential limitation. Furthermore, although the SCID-IV was used to rule out comorbid psychiatric illness, it is possible that the interview did not detect abuse of other substances. In addition, it is possible that subclinical withdrawal symptoms might have affected test performance. Longitudinal assessment of abstinent methamphetamine-dependent individuals will provide important data on the durability of these deficits.

It is likely that the severity of the neurocognitive impairment observed in this sample is associated with worse functional outcomes, including poorer vocational functioning and an elevated risk of relapse to dependence. Although the association between neurocognition and functional outcomes has not been examined in methamphetamine-dependent individuals, or in users of any drugs, it has been documented in other disorders. For example, in individuals with HIV, neurocognitive deficits have been linked to poor vocational functioning.

35,36 Similar findings have been reported for samples of individuals diagnosed as having schizophrenia.

37 In the schizophrenia literature, these deficits are associated with an inability to learn skills during the course of rehabilitation or to implement learned skills. Neurocognitive impairment may undermine the effectiveness of psychosocial treatments for methamphetamine dependence as well, suggesting that this concern is an important area of study.