The prevalence of schizophrenia is approximately 1%, and a chronic schizophrenia-like psychosis occurs in 3%–7%

1 among patients with epilepsy, particularly those with partial seizures arising from mesial temporal structures (temporal lobe epilepsy [TLE]). The phenomenology,

2 course, treatment response, and outcome of these two forms of chronic psychosis are not readily distinguishable. The schizophrenia-like psychosis of epilepsy (SLPE) offers a model of schizophrenia that is seemingly driven by temporal lobe pathology.

3 However, the similarities in structural

4 and spectroscopic

5 brain abnormalities should not be overemphasized. While these abnormalities are focal in TLE, they appear to be global in schizophrenia.

6 A comparison of the two disorders may make it possible to disaggregate those features of schizophrenia that are associated with temporal lobe pathology and those attributable to extratemporal abnormalities, most notably in the frontal regions.

A recent study from our group

7 compared cognitive performance in patients with schizophrenia and SLPE, nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy, and healthy comparison subjects. Patients with schizophrenia and SLPE had almost identical profiles. Impaired attention, executive function, and episodic—particularly verbal—memory characterized both groups. The nonpsychotic comparison subjects with epilepsy showed similar, though less marked, deficits. These findings did not support the concept of a separate SLPE syndrome.

Verbal

8–11 and visual

12 memory deficits, unrelated to specific symptoms or chronicity, have been reported in schizophrenia, but opinions are divided as to the precise pattern and underlying mechanisms. For some (e.g., McKenna et al.,

8 Saykin et al.,

13 and Duffy and O’Carrroll

14), the sparing of immediate recall relative to delayed recall points to a classic temporal amnesia. For others (e.g., Beatty et al.,

15 Paulsen et al.,

16 and Nathaniel-James et al.

17), the relative sparing of recognition memory with impaired immediate free recall suggests a pattern akin to that seen in patients with frontal lobe lesions. However, this dissociation between recall and recognition has not been consistently identified (e.g., Seidenberg et al.,

18 Blaxton and Theodore,

19 Helmstaedter et al.,

20 and Gleissner et al.

21). Only two studies

22,23 have compared the cognitive deficits of schizophrenia and TLE, although neither looked specifically at SLPE. Gold et al.

22 found that schizophrenic patients were impaired on tests of attention, motor speed, and executive function, while TLE patients performed worse on tests of memory and semantic knowledge. They concluded that temporal lobe dysfunction alone did not provide a satisfactory model for the deficits observed in schizophrenia. Seidman et al.,

23 on the other hand, reported greater similarities between the two groups, although schizophrenic subjects performed better on paired associate learning tests and benefited from retrieval cues, a pattern similar to that observed in patients with frontal lesions.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate further the differences and similarities in the cognitive performance of patients with SLPE, nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy, schizophrenic patients, and healthy comparison subjects. Subjects in the SLPE group and the nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy group participated in one of our previous studies,

7 but all were retested using a different range of neuropsychological tests that allowed us to explore the relationship between executive impairment and the pattern of memory deficits. In addition, recognition memory tests, not employed in the earlier study, were used in this study, which was intended to separate the contributions of psychosis and TLE to the pattern of cognitive deficits.

METHODS

Subjects

Four groups of subjects were examined, 12 patients with epilepsy (11 with TLE and 1 with primary generalized epilepsy) and psychosis (SLPE); 12 patients with epilepsy (11 with TLE and one with primary generalized epilepsy) without psychosis; 26 patients with schizophrenia, fulfilling RDC criteria; and 38 healthy comparison subjects. All subjects in the psychotic groups had taken part in our earlier studies.

5,7,17The diagnosis of TLE was based on the semiology of seizure description. When possible, the laterality of the focus in the 24 epileptic patients was determined by pooling data from EEG studies performed as part of their clinical assessment. The subjects in the two epileptic groups were matched for side of focus, gender, and age. The seizure frequency in the 12 months prior to entry was also matched in the two groups and ranged from 0 to 120 seizures per month. All had complex partial seizures, apart from one subject in each group who had primary generalized epilepsy. The overall mix of right- and left-sided abnormalities as detected by EEG was similar in the two groups. In the SLPE group, four had bilateral epileptiform activity (generalized and/or nonspecific) with no focal abnormalities; two had bilateral focal temporal lobe abnormalities with no clear left/right predominance; five had bilateral abnormalities, four with a left-sided and one with a right-sided predominance; five of the nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy had bilateral epileptic activity with no detectable foci; the remaining seven had bilateral abnormalities, four with a left-sided and three with a right-sided predominance. The age at onset of epilepsy was similar in the two groups: 11.3 years (SD=5.8) in patients with SLPE and 13.9 years (SD=12.6) in the nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy. All SLPE patients had chronic interictal psychosis with onset many years after the epilepsy (mean age at onset of psychosis=26.8 years, SD=6.4). Patients with epilepsy were on long-term anticonvulsants, and those with schizophrenia and SLPE were receiving neuroleptics.

Healthy comparison subjects were recruited from various sources and matched to the other groups for premorbid intelligence quotient (IQ) and gender. All subjects were right handed as assessed by the Annett Handedness Questionnaire.

24 Those drinking more than 80 gr of alcohol per week or regularly using recreational drugs were excluded, as were those with head injury leading to unconsciousness or with other neurological or systemic illness. Comparison subjects with past or present psychiatric disorders were also excluded. Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Neuropsychological Assessment

Premorbid and current intellectual functioning were estimated using the National Adult Reading Test

25 and the Raven’s Progressive Matrices (advanced set 1),

26 respectively. Verbal learning and memory were assessed using the California Verbal Learning Test.

27 Subjects were required to recall a list of 16 words (list A), which consisted of four words from each of four semantic categories, over five trials. Following an interference list presented for one trial, subjects were tested for free recall (short-delay free recall) and category-cued recall (short-delay cued recall) of list A. Following a 20-minute break, during which some of the executive function tests were administered, free and cued recall (long-delay free and cued recall) and recognition of list A were assessed. Semantic and serial clustering scores were also calculated for initial learning.

Executive function was assessed using a range of measures. First, the Verbal Fluency Test was conducted to determine fluency for the letters F, A, and S.

28 The score was the sum of all valid words within 60 seconds per trial and was corrected for gender, age, and education according to existing norms.

29 Next, subjects completed the Modified Card Sorting Test,

30 in which they were required to sort 48 cards on the basis of three categories (color, number, and shape). The total number of errors, categories achieved, and perseverative errors were recorded. The percentage of perseverative errors was also calculated. Finally, they performed the Hayling Sentence Completion Test,

31 which is a response initiation and suppression test consisting of two stimulus conditions of 15 sentences each. In the response initiation condition (condition 1), 15 sentences were read omitting the last word. Subjects were required to give a word that would plausibly complete the sentence. In the response suppression condition (condition 2), subjects were asked to produce a word unrelated to each sentence. The sum of response latencies in condition 1 and an error score based on the quality of responses in condition 2 were scored. A “correct” completion response received an error score of 3. A word semantically related to a word in the sentence received a score of 1 and a related word a score of 0.

Statistical Analyses

Analysis of variance using general factorial or repeated measures approaches appropriately was used. For simplicity, only the main effects and interactions involving the group variable are reported in detail. Age and current intellectual status, as measured by the Raven’s Matrices, were used as constant covariates in all analyses. These variables, which differed significantly between the groups (see below), might either mask or accentuate group differences in the memory and executive measures that were the focus of this study. Although the unadjusted group mean data are provided in the tables, estimated adjusted means are shown in the figures as these provide a more meaningful illustration of the results. In interpreting significant group and interaction effects, post hoc tests were performed using Bonferroni correction throughout.

RESULTS

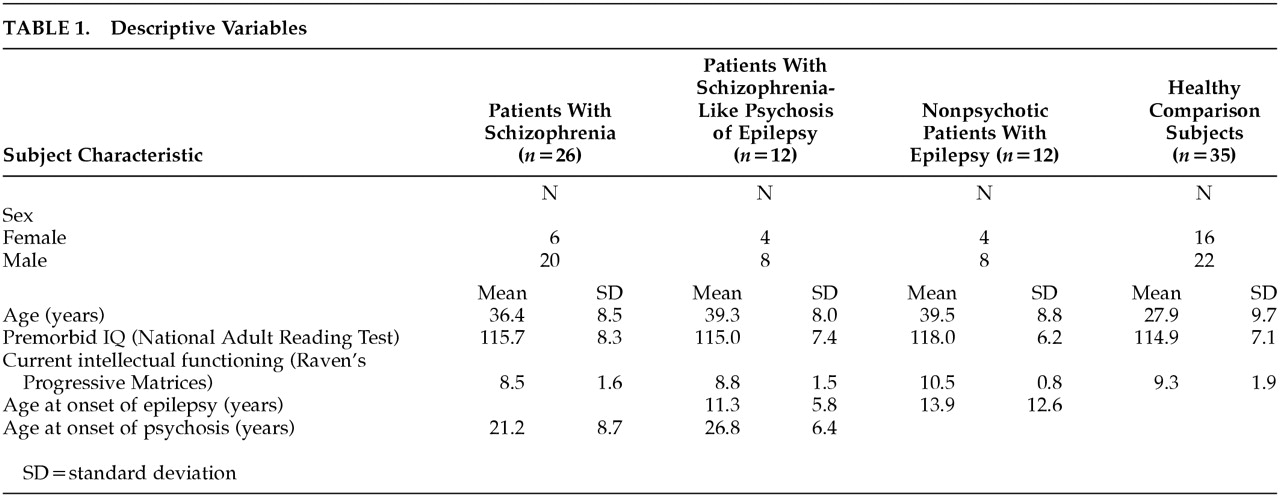

The groups did not differ in gender ratio or estimated premorbid IQ. There were significant differences between the groups in age (

F=12.5, df=3, 72,

p<0.001) and current level of intellectual functioning (

F=4.3, df=3, 72,

p<0.01) (

Table 1).

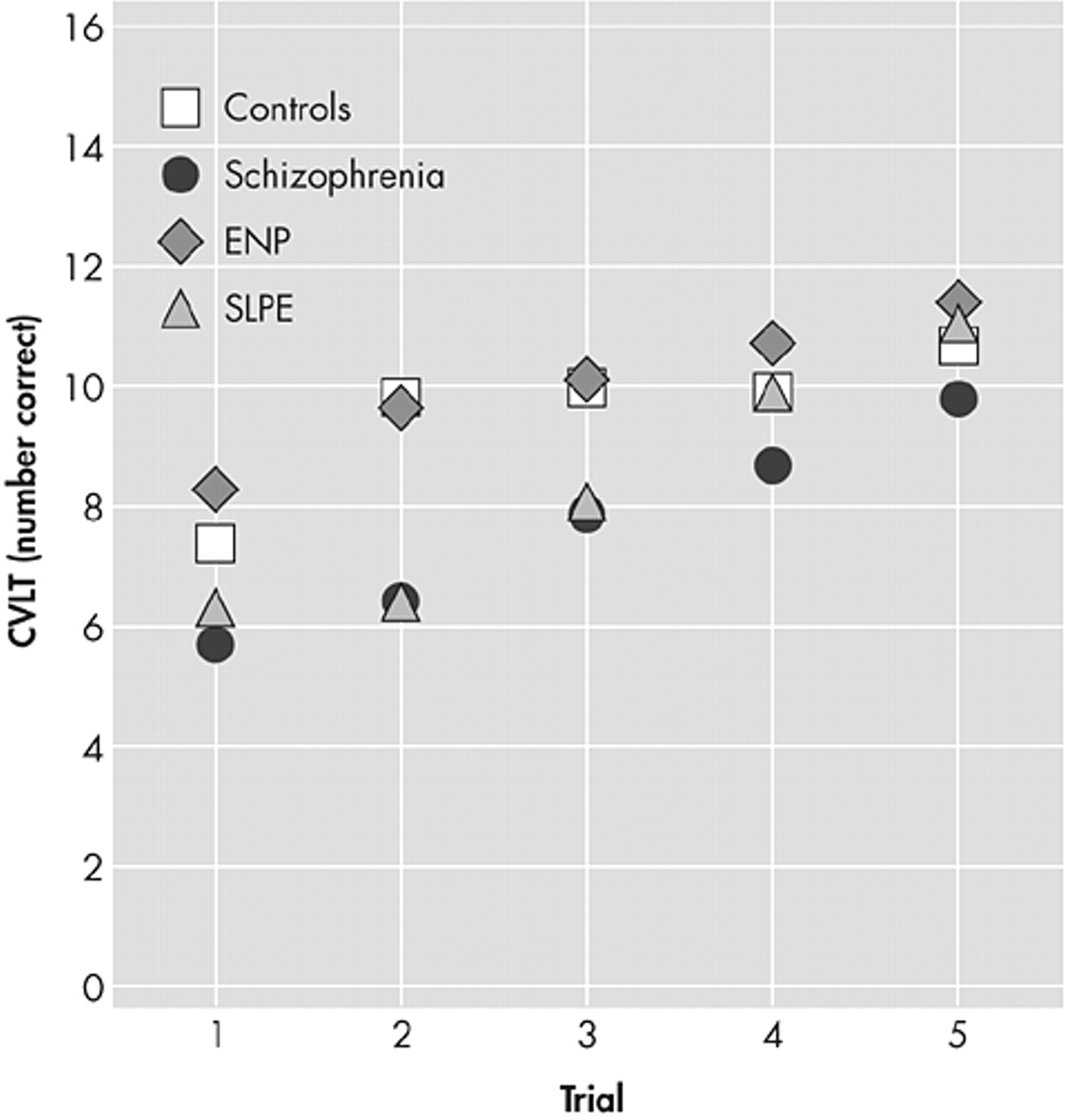

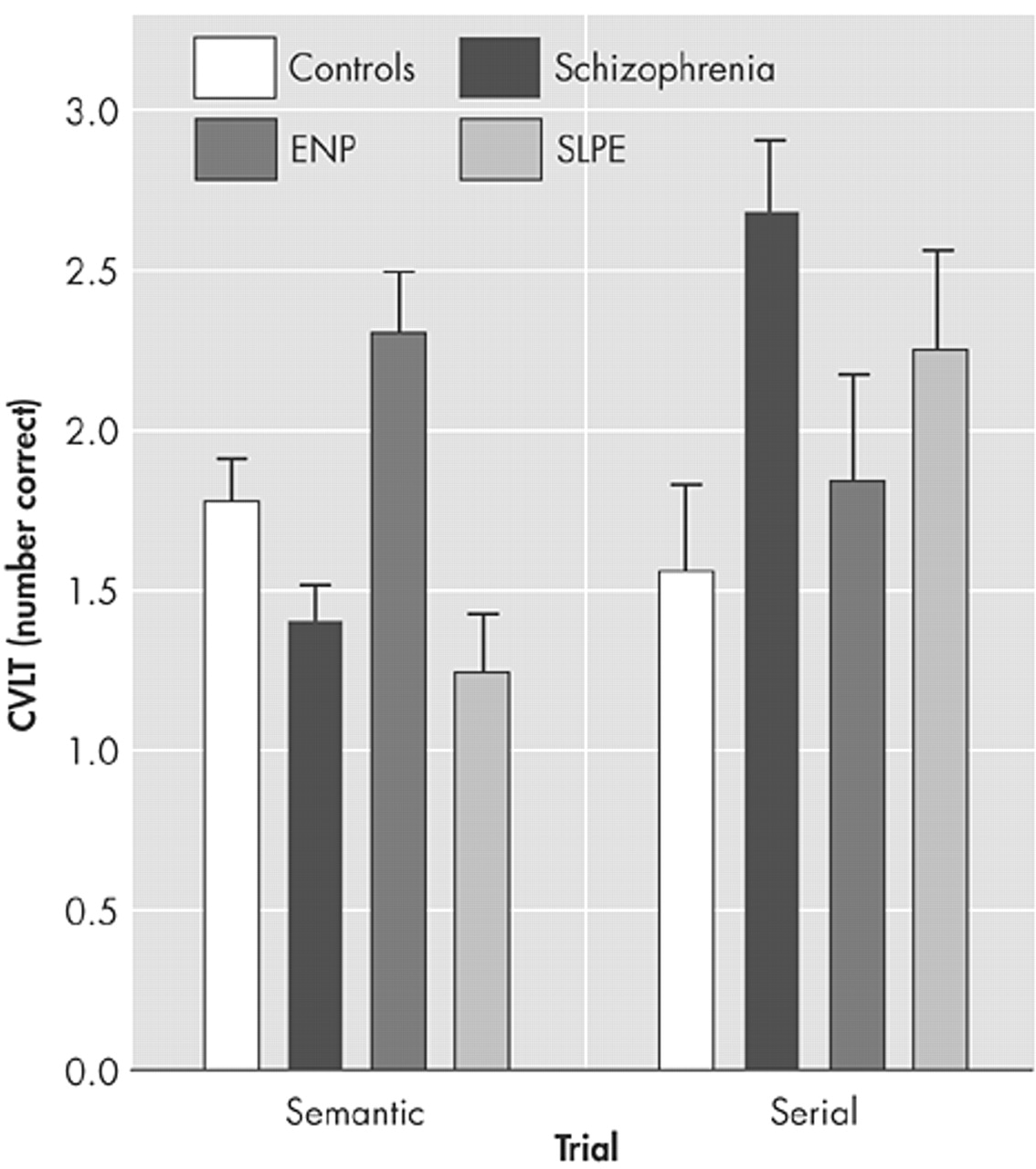

Analysis of recall over the five learning trials indicated a significant group-by-trial interaction (

F=2.8, df=12, 268,

p<0.005), arising from impaired performance of the two psychotic groups over the initial trials. Group differences during learning were found for both the semantic cluster score (

F=6.9, df=3, 66,

p<0.001) and the serial cluster score (

F=6.9, df=3, 66,

p<0.001). The healthy comparison subjects and the nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy tended to use more semantic than serial strategies, while the two psychotic groups tended to use more serial strategies (

Figure 2). However, these differences were significant (

p<0.05) for the paired comparisons of nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy and patients with schizophrenia only.

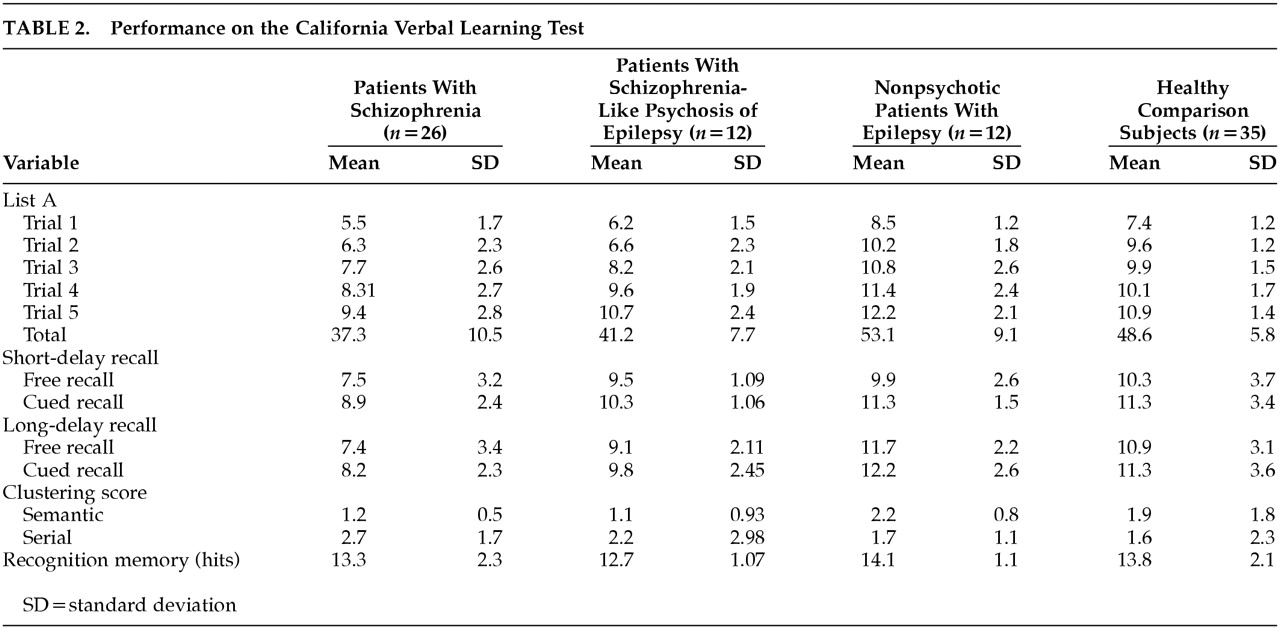

Free recall was unaffected by a short delay (

F<1, df=1, 67), while cueing led to differential improvement in recall (

F=4.0, df=3, 67,

p<0.05), with the greatest gains seen in the schizophrenia group. A differential effect was also observed in the effect of longer delays on free recall (

F=5.6, df=3, 67,

p<0.01) (

Figure 3), where a significant deterioration was observed in the schizophrenic group (

p<0.001) but not for the other groups. However, as before, the schizophrenia group was able to benefit from cueing to improve their performance relative to the other groups.

Finally, there was no significant difference between recognition memory performance in the four groups (

F=1.7, df=3, 67,

p>0.10) (

Table 2).

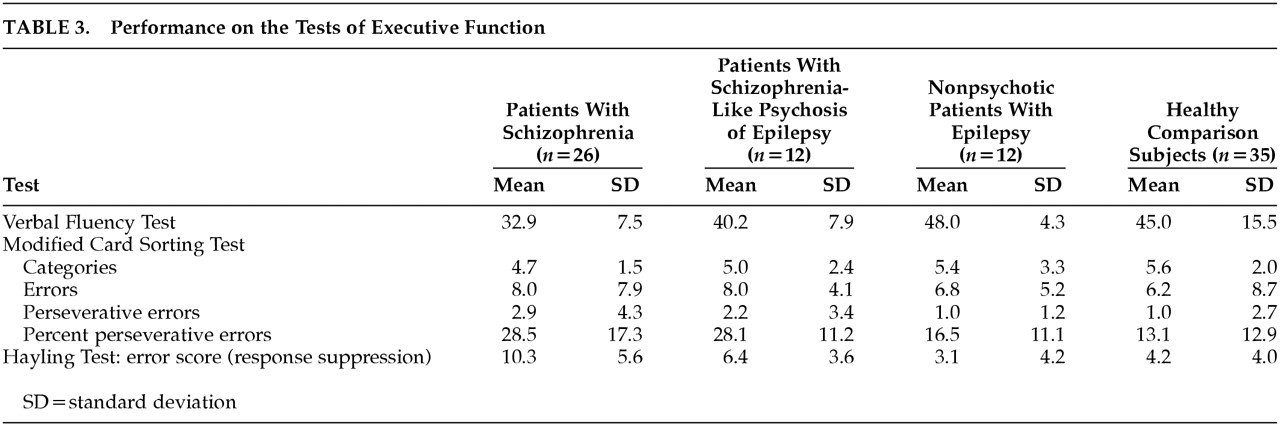

Executive Function (Table 3)

The groups differed in their performance on the Verbal Fluency Test (F=6.57, df=3, 66, p<0.01), with the schizophrenic group performing worse than the healthy comparison subjects and the nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy. On the Modified Card Sorting Test, no difference was found in the total number of categories or the total number of errors (F<1, df=3, 66). The groups differed in the number of perseverative errors (F=3.3, df=3, 66, p<0.05), with the two psychotic groups tending to perform worse, although post hoc paired comparisons failed to reveal any significant paired differences. Similar results were found with percentage of perseverative errors.

A highly significant difference was found between groups for errors on the Hayling Response Suppression Test (

F=7.6, df=3, 66,

p<0.001) (

Table 3). Post hoc tests revealed a significant impairment in the schizophrenic group that was relative to all other groups. The other three groups did not differ significantly.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study suggest a consistent pattern of cognitive deficits in the groups with schizophrenia and SLPE, with patients with schizophrenia showing the greatest impairment on executive and memory tasks. Patients with schizophrenia performed poorly on tasks of verbal learning and short and long delayed retention and benefited more from cued recall. The performance of the SLPE group on verbal learning was intermediate, between the schizophrenia group and the other groups. Both psychotic groups used serial in preference to semantic strategies, while the reverse was true for the nonpsychotic groups. All groups scored within the normal range on tests of recognition. Schizophrenic subjects scored worse on executive tasks, while the SLPE group occupied an intermediate position between patients with schizophrenia and the comparison groups.

Cognitive impairment in schizophrenia is now widely accepted, with memory and executive functions bearing the brunt.

32,33 A metaanalysis

34 has reported verbal and nonverbal memory deficits, with recall more severely impaired than recognition, suggesting poor retrieval. Furthermore, others

35 have reported a dissociation between impaired declarative and preserved nondeclarative memory, a pattern found in patients with frontosubcortical pathology. There is also recent evidence indicating deficits in working memory

36 and aberrant activation of prefrontal cortex during working memory performance.

37 These observations suggest that some aspects of memory impairment in schizophrenia may be due to deficits in executive function. The findings of this study are broadly in agreement. Schizophrenic subjects performed poorly on recall tasks and less so on recognition, and although this difference may be explained partially by differences in task difficulty, the improvement with cueing suggests a failure of retrieval mechanisms. The failure to make use of semantic strategies would also favor a dysexecutive component.

Few studies

22,23,38 have directly compared memory function in schizophrenia and TLE. Gold et al.

22,38 examined the contribution of left and right temporal pathology. Their schizophrenic group performed better on tasks of verbal memory than epileptics with left temporal lobe pathology. In these studies, as in Mellers et al.,

7 TLE subjects with and without psychosis performed better than schizophrenic subjects on tests of new verbal learning. This may reflect the fact that the TLE groups contained as many right-sided as left-sided patients in these studies. The conclusion of the study by Mellers et al.,

7 as of this study, was that temporal lobe dysfunction alone does not provide an adequate explanation for the cognitive impairment of schizophrenia. Seidman et al.

23 reported mildly impaired verbal and nonverbal memory in schizophrenic patients, as compared with those with TLE and normal control groups. Schizophrenic subjects performed best on cued verbal tests such as the paired associate learning, in which new information was nonsupraspan.

Some limitations to this study must be considered. Patients with SLPE and nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy were well matched for laterality of EEG abnormalities, but a more accurate lesion and language lateralization would have required more invasive procedures (e.g., those used in presurgical assessment) not warranted in our patients. The small size of the SLPE group, determined by the rarity of these patients, requires caution in the interpretation of the results. Similarly, the high estimated premorbid IQ of all our subjects might make our results less applicable to other populations. In addition, the small number of nonpsychotic patients with epilepsy may have obscured potential differences between patients and comparison subjects.

In conclusion, our findings support the view that cognitive decline in schizophrenia is characterized by memory impairment and executive dysfunction. The profile of cognitive impairment in SLPE resembles that of schizophrenia, but it is less pronounced. This finding does not support the concept of SLPE as a nosological entity sui generis. Rather, it argues for epilepsy as a risk factor for the development of an exogenous and relatively benign form of schizophrenia.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Professor Michael Trimble for allowing them to approach some of his patients. Dr. D.A. Nathaniel-James was supported by a grant from the Rayne Foundation and Professor M.A. Ron was partly supported by the Scarfe Trust. Finally, the authors thank all the patients and healthy volunteers for their time and effort in helping to carry out this work.