The incidence of psychiatric diseases in epileptics is significantly higher than in the general population.

1–4 Depressive and anxiety disorders are the most common psychiatric diseases in this patient group.

1 Diagnosis and treatment of depressive disorders are very important because of the significantly higher suicide rate in epileptics.

5 Although the suicide incidence reported in the literature varies significantly, it is four to five times higher than in the general population.

6,7 In an overview of the causes of death in epileptics, Robertson reported a nine- to ten-fold higher suicide rate in this group compared with the general population. Risk factors for suicide include a history of self-injuries, a family history of suicide, emotional stress-causing events, psychiatric diseases such as depression or psychosis, and alcoholism.

5,8 The available data show the urgent necessity of treating depressive disorders in epileptics. This article provides an overview of mood disorders in epileptics and their treatment.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLASSIFICATION

According to most authors dealing with this subject, depression is the most common psychiatric disease in patients with epilepsy,

5,9–11 and a significant cause of admission to a psychiatric clinic.

12 Data on the prevalence vary, depending on the patient population. An average incidence of 30%–40% is, however, assumed. In general, depression in epileptics is more frequent and more severe than in patients with other neurological disorders or chronic organic diseases.

3,13,14Obtaining precise data on depression in epileptics is difficult because the groups investigated were very heterogeneous. In particular, data from hospitalized patients and patients in tertiary facilities are not representative of the majority of epileptics. Furthermore, the interpretation of data from the literature is difficult because some studies do not distinguish between depressive symptomatology and depressive disorder.

5 However, in a Swedish study with patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy, the incidence of depressive disorders was seven times higher for these epileptics than for individuals in the comparison group. In the group of patients with focal epilepsy, a 17-fold increase of the incidence of depressive disorders was observed.

15 Four other controlled studies

16–19 showed a significantly increased incidence of depressive disorders in epileptics compared with a comparison group of subjects without epilepsy. Mania and disinhibition have been reported, but frequently have been quoted as being rare.

20,21 To date, there are only case reports and retrospective reviews with small numbers of patients regarding mania and bipolar disorder; therefore no prevalence rate for these disorders is given in the literature.

Mood disorders include major depression, mania, bipolar disorder, and dysthymia, according to ICD-10

22 and DSM-IV.

23 The clinical picture of depressive disorders in epileptics does not, however, always correspond with the criteria listed in operationalized classification systems.

11 When diagnosing a depressive disorder in epileptics, the chronological relation to the seizures must be taken into consideration. Therefore, the classification into peri-ictal, ictal, postictal, and interictal depression was established.

Peri-Ictal Depression

This depression is called preictal depression by some authors

5 who relate it to the premonitory dysphoria. Since dysphoric symptoms are observed before and after the seizure, the term “peri-ictal depression” is now used in the literature.

Depressive syndromes frequently precede the seizure. They may last hours to days and are characterized by a depressive-anxious mood, or, sometimes, by dysphoria. With the occurrence of the seizure, the symptoms often come to an end.

24 They may, however, continue for hours or days after the seizure. It is not yet known whether these premonitory depressive symptoms are a subclinical part of the seizure or if neurobiological processes, which are responsible for the depressive symptoms, induce a decrease of the convulsive threshold.

25,26 In a recent study,

27 one-third of the patients with focal seizures had peri-ictal depressive symptoms, whereas patients with generalized seizures did not show these symptoms.

Ictal Depression

Depressive symptoms may be a part of the seizure. Although anxiety is the most common affective symptom of a seizure, depressive symptoms of an aura have been observed in 1% of 2000 patients with simple focal seizures.

28 Ictal depression seems to be more common in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy; in the literature, an incidence of 10% is reported.

24,29 There was no association with the lateralization of the epileptic focus.

24,28–30 Typically, ictal depression is characterized by a sudden onset of symptoms, with no relation of the symptoms to outside stimuli. In a few case reports, depressive-psychotic symptoms are described as symptoms of a nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

31 In some cases, impulsive suicidality was observed during such an episode.

32,33Postictal Depression

This type of depressive disorder has been repeatedly described in the literature, but prevalence figures are still not available. In a recently published American study conducted in a tertiary epilepsy center, the authors observed postictal depressive symptoms with an average duration of 37 hours in 56 of 100 patients with difficult-to-control simple focal seizures.

34 In a further investigation, the authors found, in many patients with postictal depression, unilateral frontal or temporal foci, without evidence of dominance in one hemisphere.

1 After a seizure, depressive symptoms may last for up to 2 weeks.

35,36 and may also lead to suicide.

33,37–39 Blumer proposed the hypothesis that postictal depression is a consequence of the inhibitory mechanisms, which are responsible for the completion of the seizure.

40 Psychiatric diseases and a seizure frequency of less than one seizure per month were significantly associated with postictal depressions.

41Interictal Depression

Interictal depression is the most common type of depression in epileptics.

5,11,41 The clinical picture may be that of major depression, dysthymia, or bipolar affective disorder. The exact prevalence is not known. In the literature, it is estimated as 20%–70% depending on the patient group investigated.

42 Bipolar affective symptoms are very rare, whereas episodic major depression and dysthymia are common. Most authors agree that interictal depression in epileptics cannot, in most cases, be classified according to the operationalized diagnostic systems.

5,11,41 A chronic depressive course is observed in most cases. Some symptoms resemble those of dysthymia other symptoms are specific for interictal depression (

Table 1). American authors

43 suggested calling this affective disorder interictal mood disorder. Besides chronic depressive symptoms, pleomorphic symptoms are observed. These may include atypical pain and phases during which a euphoric or dysphoric affect, anxiety or phobias are predominant. Short symptom-free phases may also occur. In an investigation by Kanner, criteria for an interictal mood disorder were met in 70% of patients with interictal depression.

41 Episodes of major depression may also occur in patients with interictal mood disorder. During a chronic depressive course, patients may get accustomed to the depressive state, which may be considered natural and may therefore not be reported to the physician. Since the symptoms are not as pronounced as those of major depression, the physician may not recognize them as depressive symptoms, and treatment is not initiated. In a recently published study,

44 major depression was diagnosed in 30% of subjects, and interictal mood disorder in 25%. None of the patients received antidepressive therapy when symptoms were first reported to the physician.

Mania

Mania has been reported in patients with orbitofrontal and basotemporal cortical lesions of the right hemisphere,

9 but manic symptoms seem to be rare in patients with epilepsy.

20,21 Epileptic patients with psychotic symptoms are more easily described in the literature as schizophrenic rather than as having an affective disorder.

9 In the reported cases mania is mostly related to peri-ictal state, improved seizure control and with an epileptic focus in the nondominant hemisphere.

20,21 To our knowledge, as mentioned above, no sufficient data about the prevalence of mania and bipolar disorder in epilepsy currently exists. There have been some reports about an incidence of 1.5% for mania in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.

9PATHOGENESIS

At the present time, there is no uniform explanatory model for the pathogenesis of mood disorders in epileptic patients. A multifactorial genesis seems to be most likely. Epilepsy-specific variables such as seizure frequency, or duration of disease, are not associated with the occurrence of depression.

5,11,41On the other hand, there are indications of an increased incidence of depressive disorders in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and complex partial seizures.

45–47 The incidence of interictal depression was found to be increased, particularly when limbic structures were involved in the seizure occurrence (e.g., in mesial temporal lobe and frontal lobe epilepsy). In these cases, interictal depression was observed in 19%–65%.

48–50 In this patient group, the incidence of depressive disorders is significantly higher than in patients with generalized seizures.

8,48 Furthermore, in patients with an aura of mostly psychological symptoms, the incidence of depression is higher than in patients with other or no aura symptoms.

11,41 In an Italian study, depressive disorders were significantly more common in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy as compared with patients with juvenile myoclonus epilepsy (Janz syndrome) or diabetes.

51The significance of laterality of an epileptic focus as a possible pathogenetic factor for the occurrence of depression is controversial. Some authors believe that a focus in the left hemisphere is a predisposing factor for the occurrence of interictal depression.

2,46,52–54 In patients with complex focal seizures and interictal depression, images of single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography showed hypoperfusion and decreased glucose metabolism in the left hemisphere as compared with the right hemisphere.

50,55 Nevertheless, the significance of laterality for the occurrence of depression is still not sufficiently investigated. In another study,

56 no evidence for a pronounced depressive syndrome was found in patients with left-sided foci. However, patients with left-sided foci and contralateral temporal and bilateral frontal hypoperfusion in the SPECT showed depressive symptoms that were more severe than those in patients without alterations of perfusion.

Abnormal neurotransmission has long been considered a significant factor in the pathogenesis of depressive disorders. In particular, the role of norepinephrine, serotonin, and dopamine deficiency in the etiopathogenesis of major depression is currently being discussed.

57 In animal models for the investigation of epilepsy pathogenesis, it was demonstrated that norepinephrine deficiency caused an increased seizure frequency, whereas increased norepinephrine levels had an anticonvulsive effect.

58–61 For serotonin, the opposite (high serotonin levels: increased seizure frequency, low serotonin levels: decreased seizure frequency) has been demonstrated in animal models.

58,61 Although the role of neurotransmitters in the pathogenesis of epilepsy is not yet clear, there are indications that neurochemical processes are possibly involved in the comorbidity of epilepsy and depression. Jobe et al.

62 provided a detailed overview of this interesting topic.

It has long been known that pharmacological antiepileptic treatment may induce negative psychotropic effects.

63–65 Phenobarbital and phenytoin may induce depressive symptoms; an increased, sometimes impulsive, suicidality is sometimes observed under treatment with primidone.

66 The risk of depression is increased with administration of newer antiepileptics such as tiagabine,

67 vigabatrin,

68 topiramate,

69 and felbamate.

70 Anticonvulsants may also have positive psychotropic effects. The mood-stabilizing effects of carbamazepine and the antimanic effects of valproate have been described in detail.

57,71 Lamotrigine, gabapentin, and topiramate have been used successfully in the treatment of bipolar affective disorders.

69,72,73 There are reports about the induction of mania with zonisamide

74 and topiramate.

75Included in the multifactorial genesis are hereditary factors, which play an important role. A British investigation demonstrated that half of all patients with epilepsy and depression had a family history of affective diseases.

76After a surgical procedure for treatment of epilepsy, the risk of developing a depressive disorder is increased for a period of 3 to 6 months. Patients with a history of affective diseases are particularly at risk.

5,43 Depression is most commonly associated with persistent seizures but may also develop as alternative symptoms in successfully treated patients.

5,77 In patients with an improved quality of life due to a reduced seizure frequency after surgery, depression is significantly less common.

78Psychosocial factors play a significant role in the genesis of depressive symptoms as seizure prodromes. To suffer from a potentially chronic disease that requires pharmacological treatment for many years and is still associated with pronounced social stigmatization, is a considerable burden. In particular, the loss of autonomy (driving restrictions, occupational limitations, problems regarding insurance), the high unemployment rate of epileptics, family difficulties, and problems with partners due to drug-induced decrease in libido may lead to depression and dysphoria.

32,79In summary, mood disorders in epileptics have a multifactorial pathogenesis which includes neurobiological, pharmacological, and psychosocial factors.

TREATMENT

Despite the high prevalence of depressive disorders in epileptics, there are very few controlled studies on antidepressive treatment. There exists only one double-blind, placebo-controlled study on the effectiveness of two antidepressants in the treatment of major depression in patients with epilepsy.

80 Preictal and ictal depression do not usually require antidepressant treatment; improvement in seizure frequency should reduce the occurrence of these forms of depression.

5 Regarding post-ictal depression, Blumer

40,43 suggested from clinical observations that proconvulsive antidepressant medication in lower doses than usual, along with optimal control of the epilepsy, would be the treatment of choice. Usually antidepressant therapy will be necessary in patients suffering from interictal depression or comorbid depressive disorders.

5,11If depression occurs, it should be determined whether the patient takes an antiepileptic drug with a known depression-inducing effect, or if treatment with an antiepileptic drug with mood-stabilizing effects was discontinued. In the first case, replacement by an antiepileptic drug with mood-stabilizing effects such as carbamazepine, valproate, lamotrigine, gabapentin or topiramate can be considered. In the latter case, the discontinued agent should be readministered.

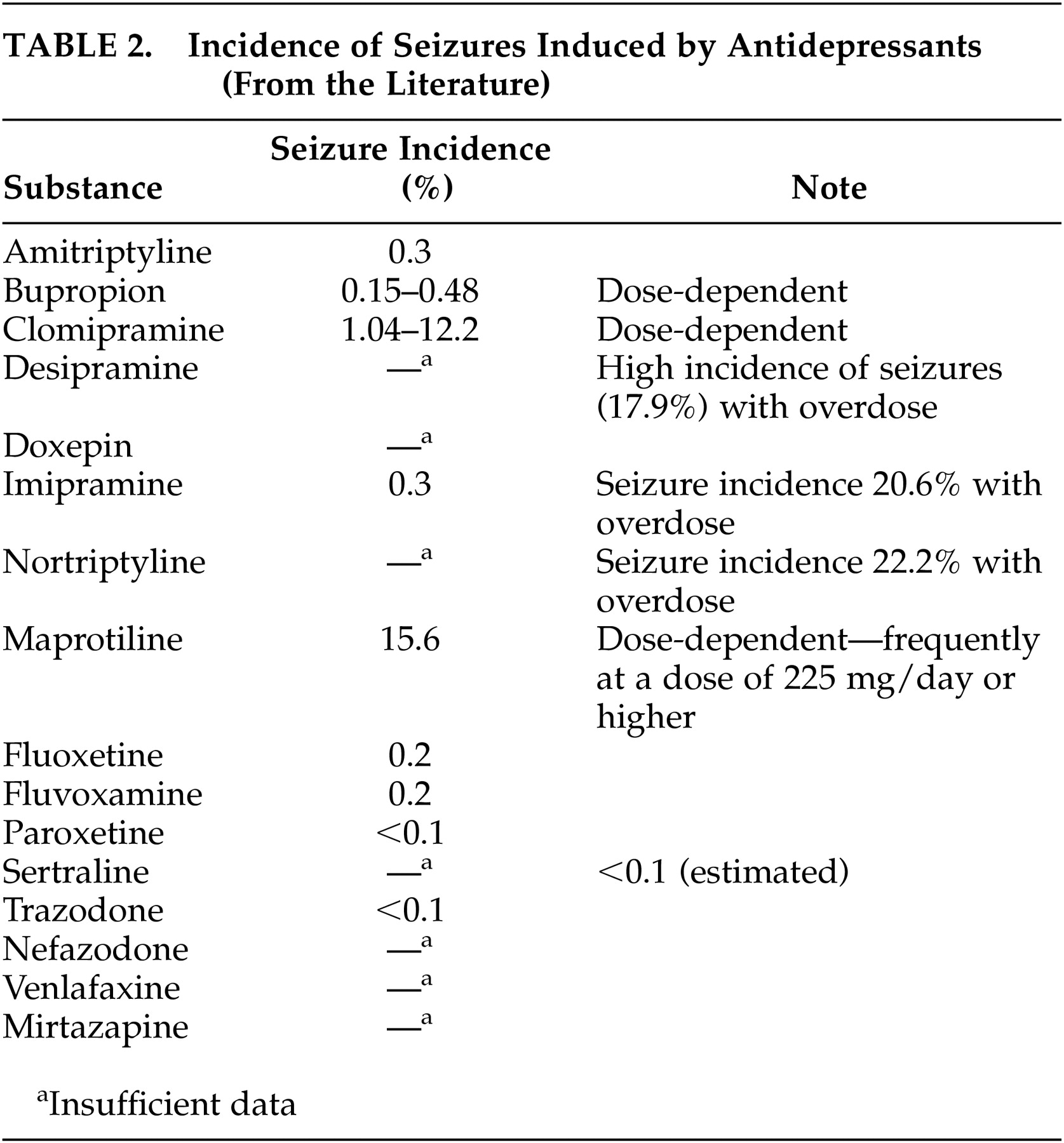

5,11,41Since antidepressants have proconvulsive properties, physicians frequently have doubts about treatment with these agents. An increased seizure rate has been described in patients without a history of epilepsy with virtually all antidepressants; the seizure incidence is 0.1% to 0.5%.

81 More frequent seizures were reported with higher doses of maprotiline, a tetracyclic antidepressant, and with clomipramine with a dose-dependent seizure incidence between 3.00% and 12.2%.

9 According to recent reviews

5,9,11 treatment with bupropion in patients with epilepsy can not be generally recommended, because of a seizure incidence of 0.15%–0.48%, especially with higher dosages. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors seem to have a lower epileptogenic potency, whereas older tricyclic substances induce seizures more frequently.

82 In a systematic investigation, Jabbari et al.

83 found a seizure incidence of 2.2% in patients without a history of seizures treated with different antidepressants. The seizures occurred after long-term treatment with high doses of tricyclic antidepressants or after rapid dosage increases (more than 25 mg/day). The seizure rate was higher in patients treated with noradrenergic antidepressants than in those receiving serotonergic agents. Under treatment with serotonin-selective antidepressants, seizures were only described in case reports.

84,85 Clinical investigations showed that venlafaxine

41,86 and nefazodone

5 did not induce seizures, even in epileptics. Some authors

87 believe that the epileptogenic effects of antidepressants do not normally present a problem if appropriate antiepileptic agents are administered and that the occurrence of seizures is related to dose and plasma level.

Table 2 presents data from the literature on the incidence of seizures under treatment with individual antidepressants. The reported data were obtained from patients without a history of epilepsy. These data remind us again about the importance of controlled studies with epileptics to investigate the epileptogenic potency of the various antidepressant classes and develop pertinent regimens for the treatment of depressive disorders in epileptics. At the present time, recommendations for the pharmacological treatment of epileptics with depressive disorders, derived from the currently available data, include treatment with substances that rarely or never induced seizures in other patient groups. Based on this statement, treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) can be recommended as first-line treatment.

5,11,41 These substances are only slightly proconvulsive and are effective in the treatment of chronic dysthymic disorders. Citalopram and sertraline can be considered first-line SSRIs because of their minimal pharmacokinetic interactions with antiepileptic drugs.

9,11 In agitated patients who need treatment with sedative preparations, mirtazapine can be considered a treatment option. Seizures under treatment with this agent were, according to the literature, only observed in a few patients.

5,88 In general, dosages should be increased carefully and in small increments. Regular EEG recordings are recommended.

Besides proconvulsive properties, pharmacokinetic interactions of antidepressants with antiepileptic drugs must be considered. The metabolism of antidepressants may be significantly accelerated by concomitant administration of enzyme inducers such as carbamazepine, phenytoin, phenobarbital, or primidone. An insufficient antidepressant effectiveness may be due to antidepressant levels that are too low. On the other hand, some SSRIs are potent inhibitors of the cytochrome P-450 enzyme system and may significantly increase the serum levels of some antiepileptic drugs and therefore the risk of toxic side effects. Fluoxetine, fluvoxamine and paroxetine are known to have these effects. Sertraline and citalopram have, however, a lower potential for interactions.

41,86 Basically, serum levels of antidepressants and antiepileptics should be determined regularly in patients receiving these medications.

Administration of lithium in epileptics has a secondary place because of its known association with encephalopathy especially when used in combination with carbamazepine.

9 Lithium has been considered proconvulsant and induces EEG abnormalities

5,11 but has been safely used in studies by Shukla et al.

89 Considering their proven efficacy, antiepileptic drugs such as valproate, carbamazepine, lamotrigine, gabapentin and topiramate should be regarded as first choice drugs for the treatment of manic episodes or bipolar disorders in patients with epilepsy.

5,11,41 Lithium can be a second-line alternative treatment and may prove useful when part of an augmentation strategy.

9Interestingly, the use of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is not contraindicated in epileptics

90 and should be considered in patients with severe, treatment-resistant depression and sometimes can also be useful with manic episodes. The incidence of seizures after ECT is not increased in epileptics as compared to patients without a history of epilepsy.

90 Several studies demonstrated that ECT increases the convulsive threshold by 50%–100% (overview in reference 91). There are also reports of successful treatment of seizures by ECT in epileptics who did not respond to various antiepileptic drugs.

91,92 ECT is therefore a treatment option for epileptics with treatment-resistant depression.

In recent years, there have been increasing indications for successful treatment of major depression with repeated transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS).

93–95 Only rTMS with a frequency rate of 5–25 Hz seems to be effective. Single pulse technique, frequently used in neurological diagnostics, is not effective.

96 Data in the literature about the use of TMS in epileptics are not uniform.

97 With low-frequency stimulation, there were indications of inhibition of the excitability of the motor cortex.

98 On the other hand, epileptic seizures induced by rTMS were described in a few case reports. Dhuna et al.

99 reported on the induction of two grand mal seizures in a patient with temporal lobe epilepsy. In this case, the hemisphere contralateral to the epileptic focus was stimulated. Two reports describe generalized seizures induced by rTMS in healthy volunteers.

100,101 Based on these insufficient data, use of rTMS for treatment of depression in epileptics cannot be recommended.

According to studies published up to the present, vagus nerve stimulation seems to be another very promising procedure in the treatment of therapy-resistant depression.

102,103 There were indications of an antidepressive effectiveness in clinical observations of improved mood and cognition among epileptics in controlled studies on vagus nerve stimulation,

104,105 as well as in direct investigations of the effects of vagus nerve stimulation on affective symptoms.

106 The neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin play a significant role in the pathogenesis of depression, and increased noradrenergic and serotonergic neurotransmission caused by the stimulation of the locus caeruleus is assumed to be the antidepressive mechanism of action.

103 It was demonstrated in animal experiments that vagus nerve stimulation activates the locus caeruleus, the nucleus in the brain with the highest density of noradrenergic neurons.

107 In the cerebrospinal fluid of epileptics treated with vagus nerve stimulation, 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid, a metabolic product of serotonin, was significantly increased.

108 The antidepressive effectiveness of vagus nerve stimulation in epileptics may have been due to a reduced seizure frequency. Mood-improving effects were, however, also observed in patients with seizure rates that were not reduced.

106 The first controlled study included patients with treatment-resistant major depression and showed an antidepressive effect of vagus nerve stimulation, even in psychiatric patients without epilepsy. Further studies are needed before a general treatment recommendation can be given. Nevertheless, based on the reported literature, vagus nerve stimulation can be considered a potential treatment option in epileptics who suffer from depression and treatment-resistant seizures.

At the present time, data supporting a benefit of psychotherapy are not sufficient. However, supporting psychotherapy should be included in the basic therapy of epileptics with depression. With cognitive-behavioral treatment, dealing with the disease may become easier, and appropriate coping strategies may be developed.