The concept of postconcussional syndrome (PCS), which refers to a symptom cluster following traumatic brain injury (TBI),

1 has gained significance in light of recent data showing that incidence of mild TBI is much higher than previously thought. According to a 2003 report by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC),

2 mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) results in approximately 500,000 emergency department (ED) visits without hospitalization and almost 200,000 hospitalizations per year in the U.S. Given the high incidence of mild TBI and publication of diagnostic criteria for PCS,

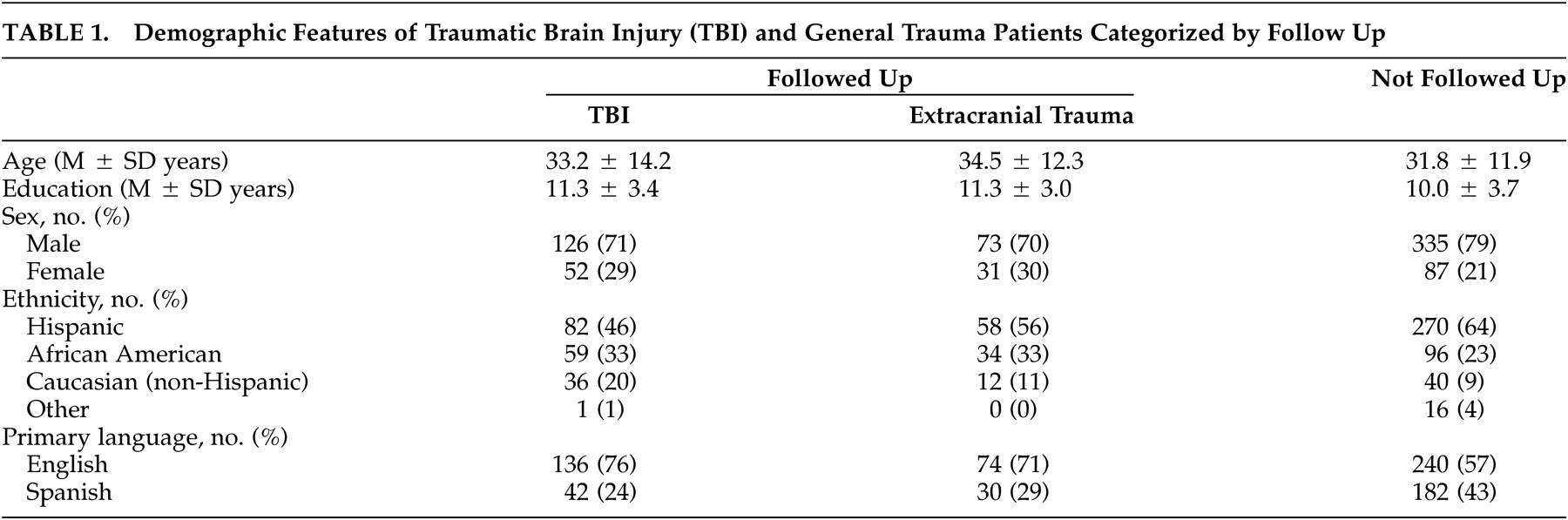

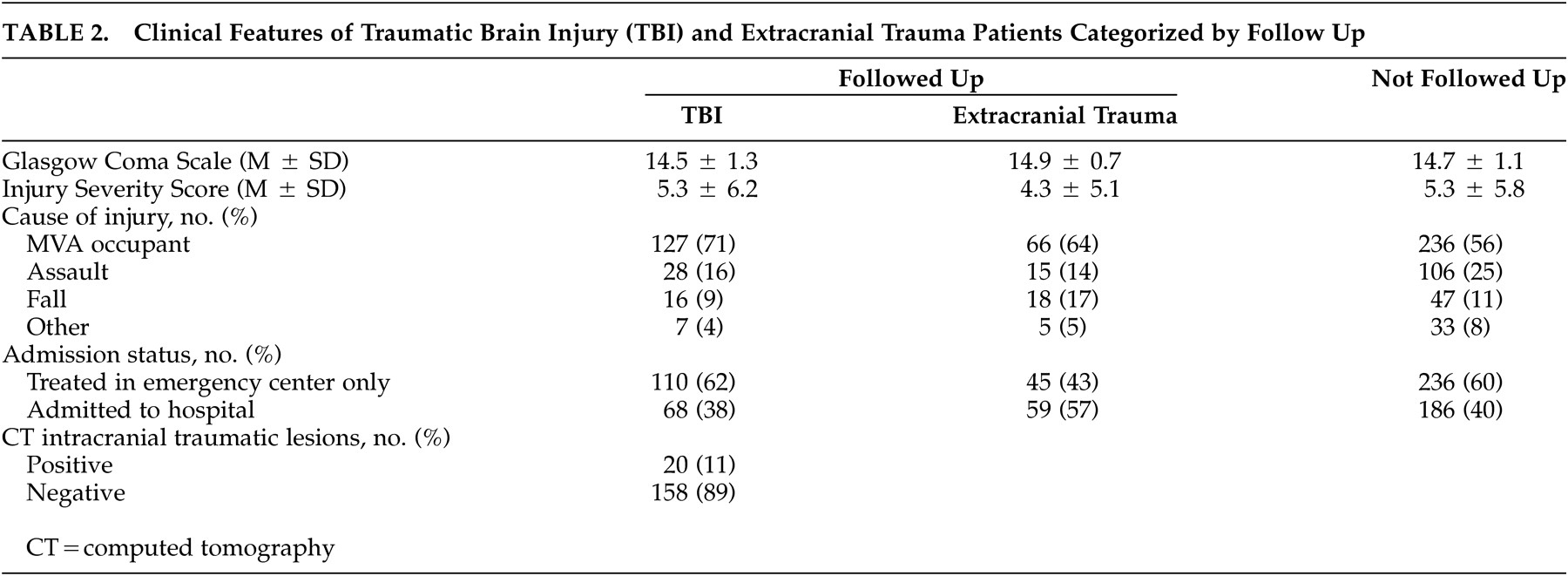

3–5 it is surprising that no prospective studies on the criteria-based diagnosis of PCS are available. To our knowledge, this study is the first to prospectively measure the prevalence of the criteria-based diagnosis of PCS and to evaluate the specificity of PCS diagnostic criteria to brain injury. Results of this study may be important in refining diagnostic criteria and to guiding clinical decision making.

Diagnostic criteria for PCS were first proposed in 1992 in the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), which included clinical and research criteria sets for PCS (Code F07.2).

3,4 ICD-10 clinical criteria

3 require a history of TBI and the presence of three or more of the following eight symptoms: 1) headache, 2) dizziness, 3) fatigue, 4) irritability, 5) insomnia, 6) concentration or 7) memory difficulty, and 8) intolerance of stress, emotion, or alcohol. During preparation of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV), the diagnosis of postconcussional disorder was proposed.

6 Criteria for this diagnosis were published in modified form in a DSM-IV appendix of provisional criteria sets designated as needing further research.

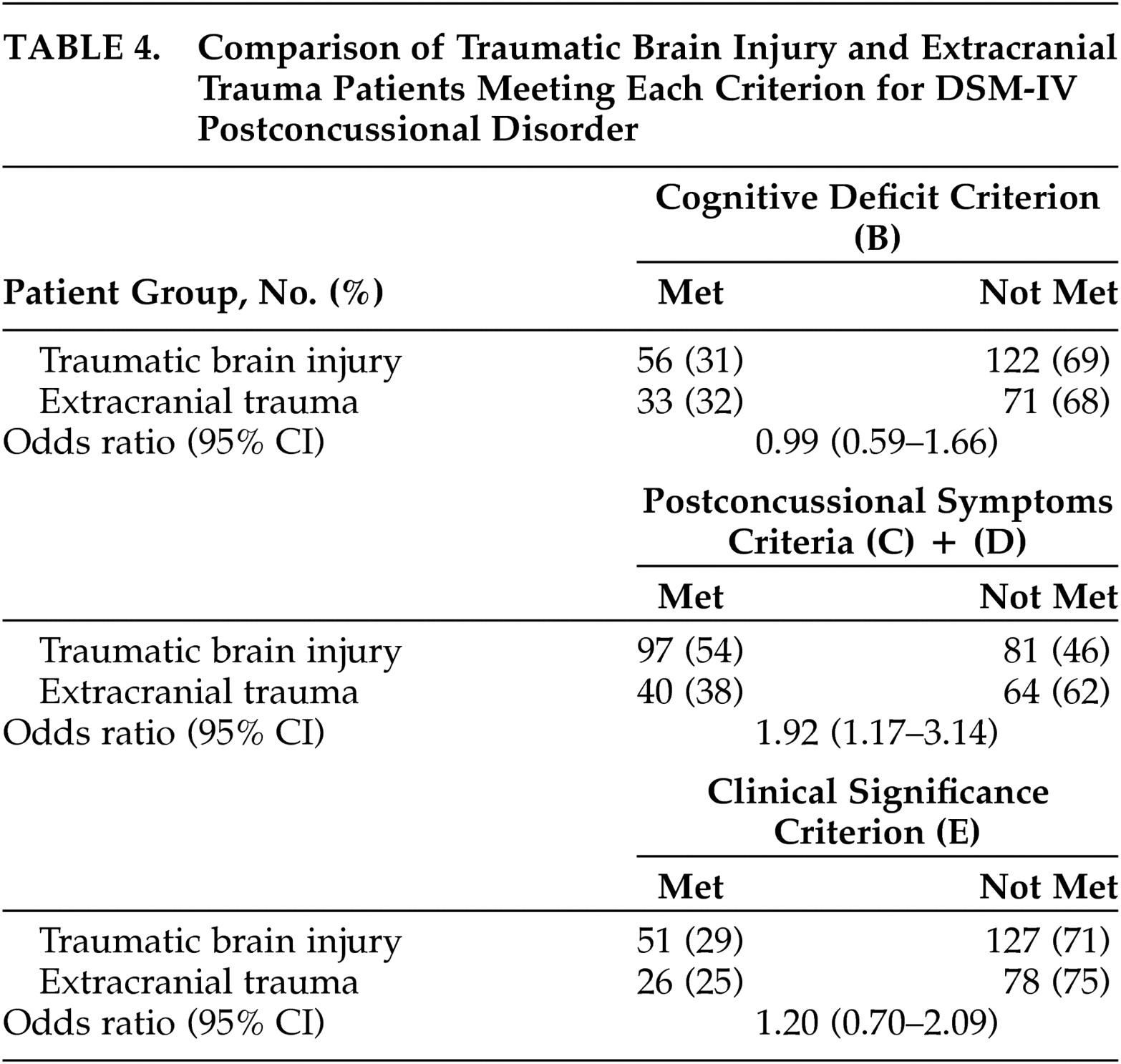

5 DSM-IV criteria are: A) history of TBI causing “significant cerebral concussion;” B) cognitive deficit in attention and/or memory; C) presence of at least three of eight symptoms (e.g., fatigue, sleep disturbance, headache, dizziness, irritability, affective disturbance, personality change, apathy) that appear after injury and persist for ≥3 months; D) symptoms that begin or worsen after injury; E) interference with social role functioning; and F) exclusion of dementia due to head trauma and other disorders that better account for the symptoms. Criteria C and D set a symptom threshold that requires symptom onset or worsening to be contiguous to the injury, distinguishable from pre-existing symptoms, and have a minimum duration.

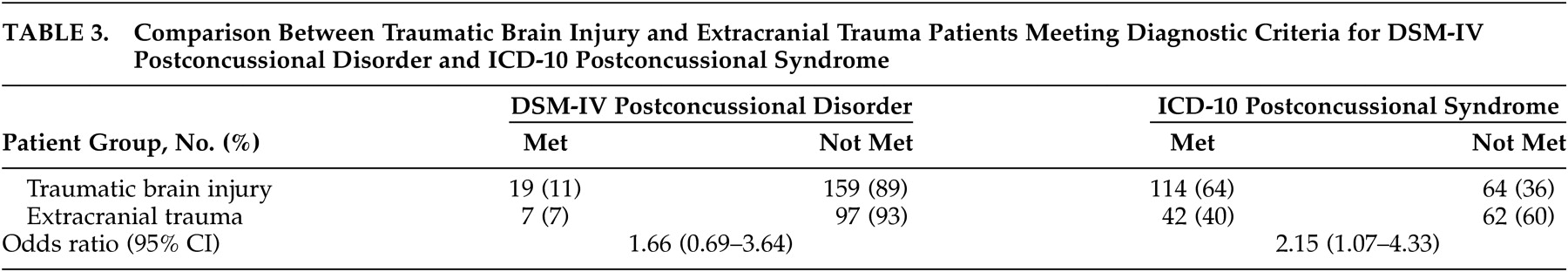

We hypothesized that ICD-10 criteria would be more inclusive than DSM-IV criteria, that both ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria would be fulfilled more often by patients with brain injury than by those with extracranial trauma, and that DSM-IV criteria would have greater specificity to TBI.

DISCUSSION

This is the first prospective study to describe the prevalence and specificity of the criteria-based diagnosis of PCS and to compare between DSM-IV postconcussional disorder and ICD-10 PCS. The results address the recommendations by CDC for research on symptoms following mild TBI

2 and by the World Health Organization (WHO) Task Force on Mild TBI

15 for studies to prospectively compare outcomes after mild TBI with appropriate control groups. The major findings are that there was a large difference between the prevalence of PCS using DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria, that ICD-10 criteria were the more inclusive of the two criteria sets, and that the DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria sets both had limited specificity to brain injury because PCS criteria can be met after trauma whether or not the brain is injured.

The higher prevalence of ICD-10 PCS, which was predicted based on the smaller ICD-10 criteria set, was observed in patients with and without brain injury. The lower prevalence of DSM-IV postconcussional disorder can probably be explained by the exclusion of the majority of patients by the DSM-IV cognitive deficit and clinical significance criteria. Although the DSM-IV criteria define a higher symptom threshold, requiring a 3-month duration and discriminability from preexisting symptoms, inequality of symptom thresholds was not a major discriminating factor.

The limited specificity of both PCS criteria sets to brain injury can probably be explained by the fact that PCS criteria (other than the history of TBI criterion) were often fulfilled by trauma patients who did not have injury to the brain. Because the DSM-IV cognitive deficit and clinical significance criteria were not specific to TBI, they did not improve the specificity of the DSM-IV criteria set. Future research could compare symptom reports to neuropsychological test results in order to determine if the TBI and extracranial trauma patients differ in over- or underestimating their true impairments. Our findings do not necessarily imply that the ICD-10 criteria have greater specificity to TBI, because a direct comparison between the DSM-IV and ICD-10 odds ratios did not reach conventional statistical significance. In addition, the relatively low prevalence of the DSM-IV postconcussional disorder would have curtailed the power of statistical tests with this criteria set.

To implement the DSM-IV cognitive deficit and exclusion criteria, some ad hoc decisions were necessary. First, in order to maximize detection of cognitively impaired patients, we set the threshold for cognitive deficit to be very low. The alternative strategy would have been to set the cognitive deficit threshold higher, for example by requiring a greater number of abnormal test scores. This alternative strategy would have reduced the prevalence of cognitive deficit in all patients, without changing the difference in prevalence of cognitive deficit between the TBI and extracranial trauma groups. Additional problems of the DSM-IV cognitive deficit criterion are that cognitive impairment after TBI tends to resolve by 3 months postinjury, as concluded by the recent WHO task force,

16 and that the criterion is incompatible with ICD-10 research criteria.

4 There is a structural incompatibility between the DSM-IV cognitive impairment criterion and the ICD-10 criteria for research (different from the ICD-10 clinical criteria used in this study) which exclude the diagnosis of PCS in the presence of cognitive impairment.

4The diagnosis of DSM-IV postconcussional disorder is to be excluded when a patient meets criteria for Dementia Due to Head Trauma, which is probably rare after mild TBI, and when another mental disorder better accounts for the symptoms.

5 In this study we decided to allow the diagnosis of postconcussional disorder in patients who met criteria for other anxiety and mood disorders, since DSM-IV does not exclude this possibility. Exclusion of postconcussional disorder in these cases would have further widened the discrepancy between the prevalence of DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria.

Strengths of this study include the prospective cohort design, defined source population and sampling frame, appropriate comparison group, sample size, inclusion of nonhospitalized patients, and evaluation of attrition bias.

15 Limitations of the study are, first, that attrition was substantial and was associated with demographic background. However, attrition bias for injury severity was not detected and there was no evidence that attrition influenced the prevalence or specificity of PCS criteria. Second, prevalence of PCS could have been overestimated in brain-injured patients because the purpose of the study was disclosed to patients and because injury history was not concealed from the interviewers. Third, the single follow-up evaluation at 3 months postinjury did not allow for change in PCS prevalence to be measured. Requiring a shorter symptom duration in patients evaluated before 3 months after injury might have caused the prevalence of DSM-IV postconcussional disorder to be overestimated. Fourth, recruitment was confined to a single trauma center, excluding patients who were untreated or who were treated in nonhospital settings. Finally, by excluding patients with GCS scores <8, the results do not address PCS after severe brain injury.

Our finding of a large difference in prevalence between the DSM-IV and ICD-10 diagnoses, if confirmed in future research, would imply that the two PCS criteria sets will often result in diagnostic disagreement. The observed frequency of PCS symptoms in patients without brain injury supports the recommendation of the CDC report

2 that complaints of postconcussional symptoms are not sufficient to make the diagnosis of mild TBI. The findings also support the WHO task force

16 criticism that in diagnosing PCS, linking residual symptoms to TBI is the major problem. These difficulties suggest that refinement of the PCS diagnostic criteria of DSM-IV and ICD-10 is needed before the criteria can be recommended for routine use.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by grants R49/CCR612707-01 (Depression after Mild to Moderate Traumatic Brain Injury, Principal Investigator: Harvey S. Levin) from the Centers for Disease Control and H133A70015 (Traumatic Brain Injury Model System of TIRR; Principal Investigator: Walter M. High, Jr.) from the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research.

This study was also presented in part at the meeting of the International Neuropsychological Society, Toronto, Ontario, Canada, February 13–16, 2002.