Essential tremor (ET) is perhaps the most common adult-onset movement disorder.

1,2 It is a sporadic or familial disorder characterized by postural-action tremor, with a frequency of 5–8 Hz. ET predominantly involves the hands but may also spread to the head, the vocal cords, the lips, and, rarely, the lower extremities.

3,4 Clinically, ET progresses slowly. In some cases in the advanced stage, daily living activities, such as eating and writing, may become impaired.

5,6 Although postural-action tremor is the most common symptom of ET, other extrapyramidal symptoms (e.g., rigidity, bradykinesia, rest tremor, gait abnormalities) and cerebellar dysfunction (e.g., intentional tremor) have been reported in patients with ET.

7–13The pathophysiological basis of ET is still controversial.

14 Neuropathological studies have not identified any evidence of morphological and biochemical abnormalities in the brains of ET patients.

15 However, some clinical and brain metabolic imaging studies suggest that cerebello-thalamo-cortical loops may have a role in the pathophysiology of ET. For example, lesions of cerebellum, pons and thalamus have been reported to abolish or reduce ET.

16–19 Positron emission tomography studies have demonstrated bilateral cerebellar hyperactivity in ET. Furthermore, magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies have revealed cerebellar neuronal damage or loss in patients with ET.

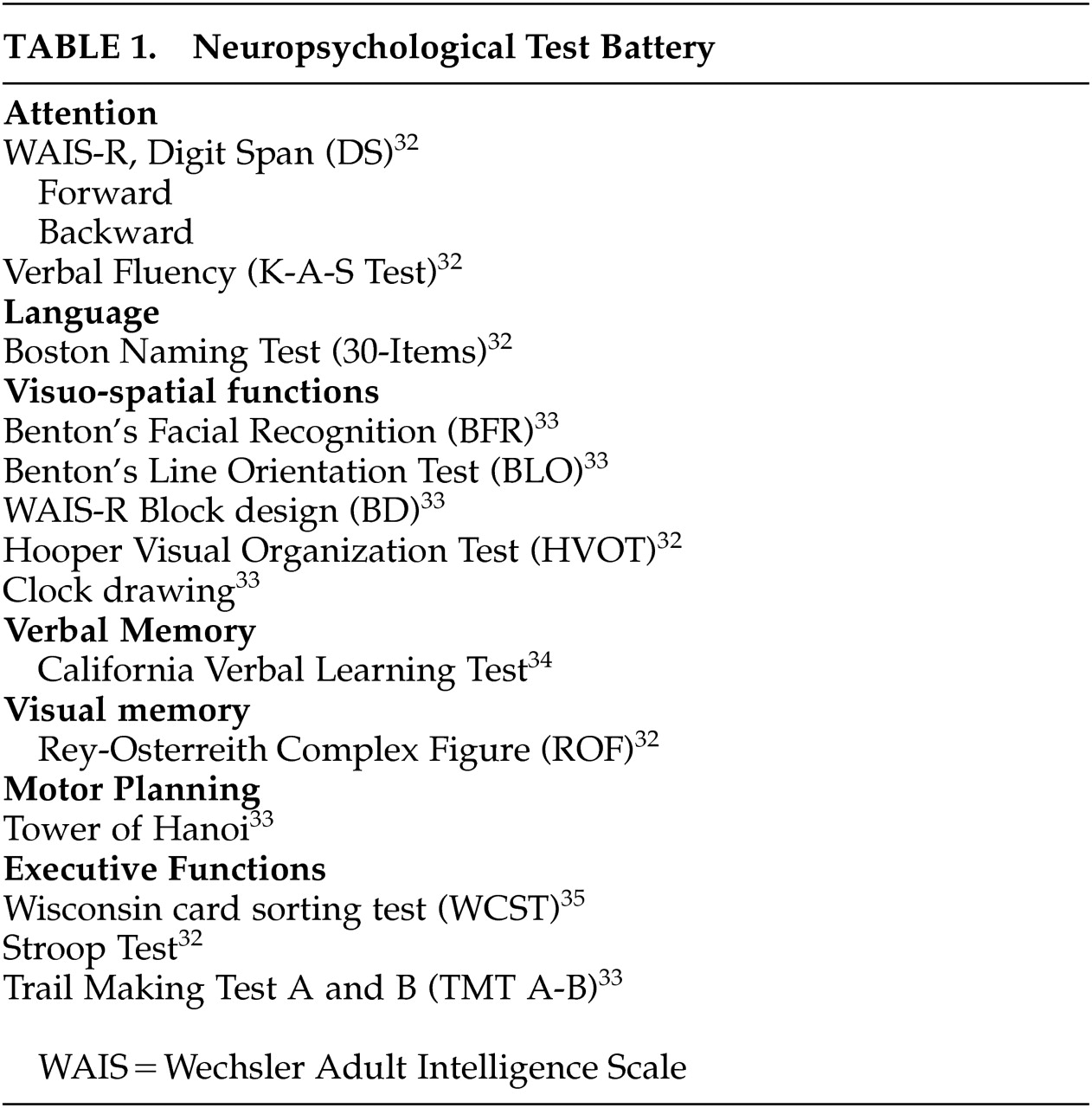

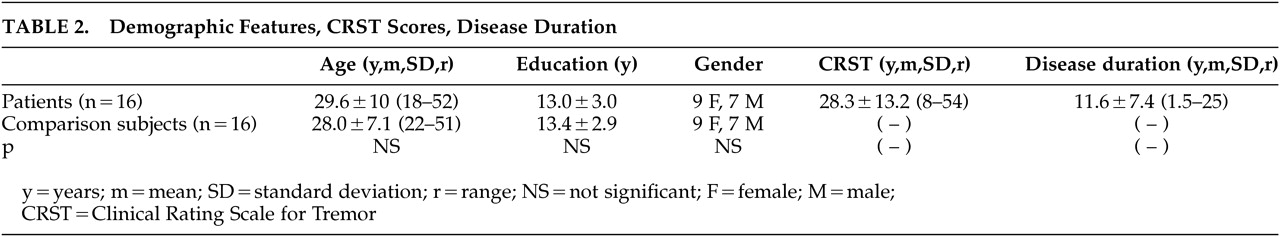

20–24Unlike the studies mentioned above, we examined cognitive functions in a newly diagnosed, nonmedicated, relatively young patient group with ET and comparison subjects using a comprehensive neuropsychological test battery in order to eliminate confounders.

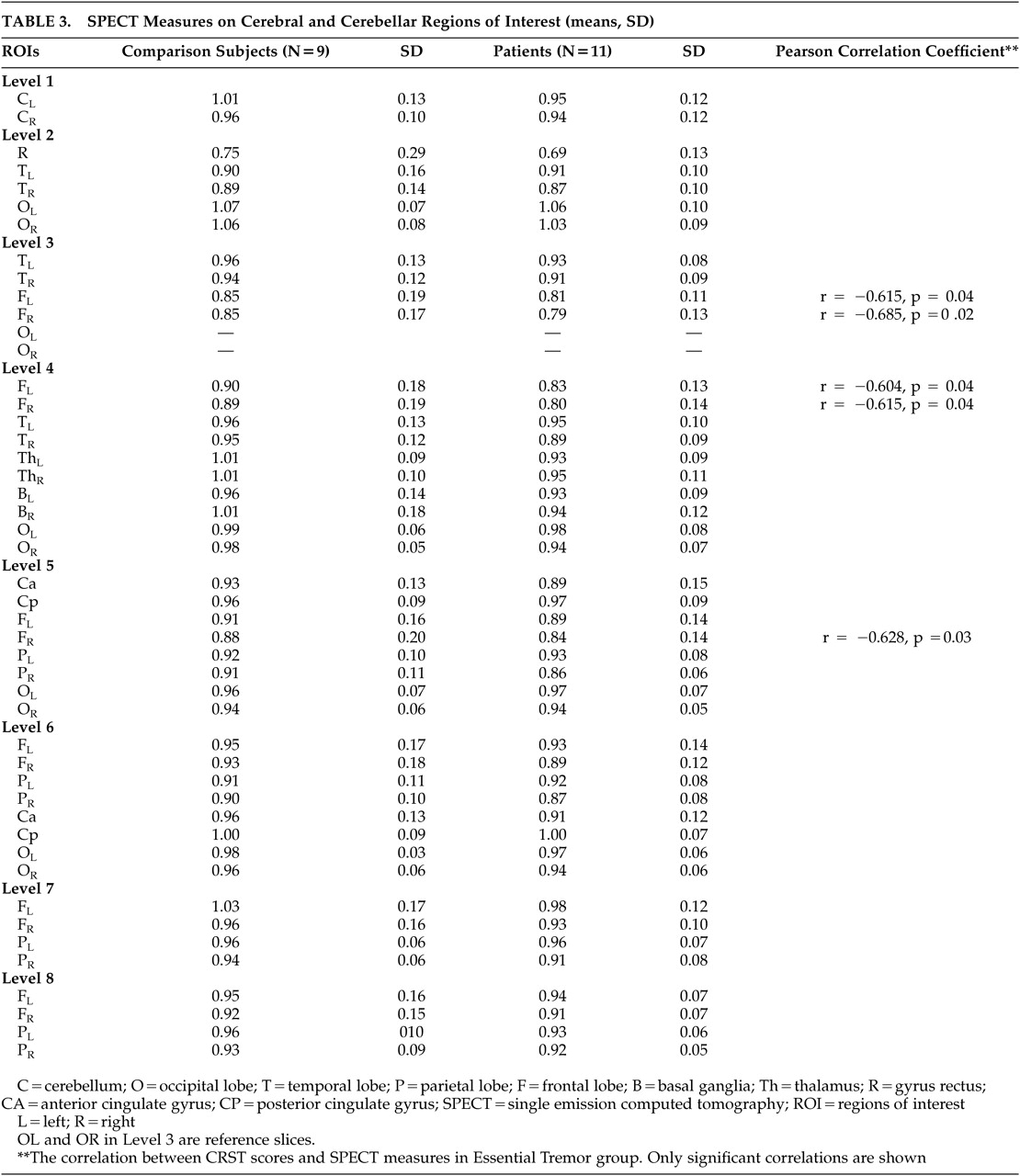

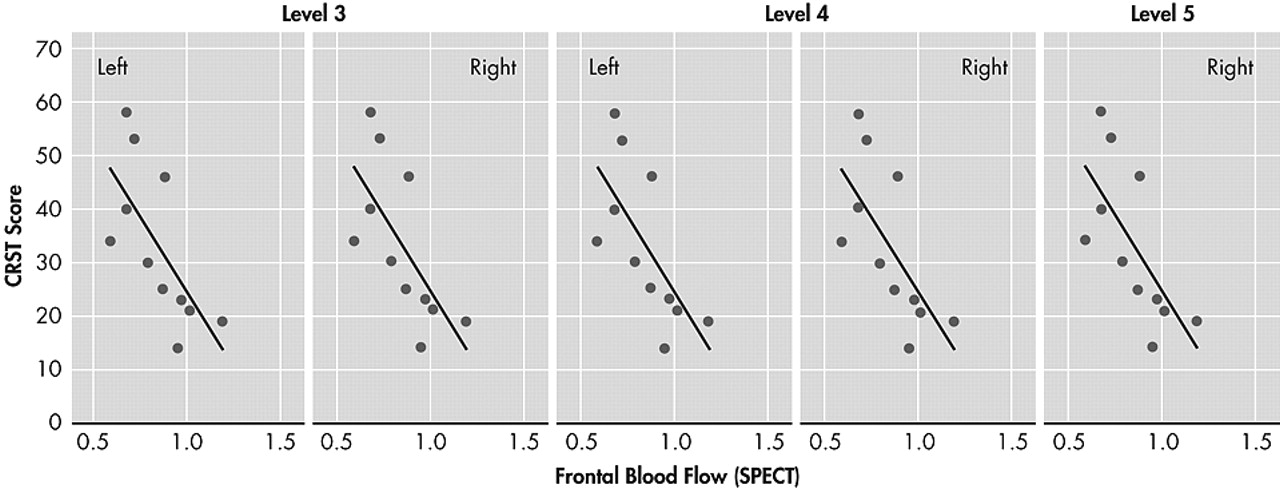

Previous studies reported inverse correlation between the regional brain blood flow by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and the poor performance on the neuropsychological tests.

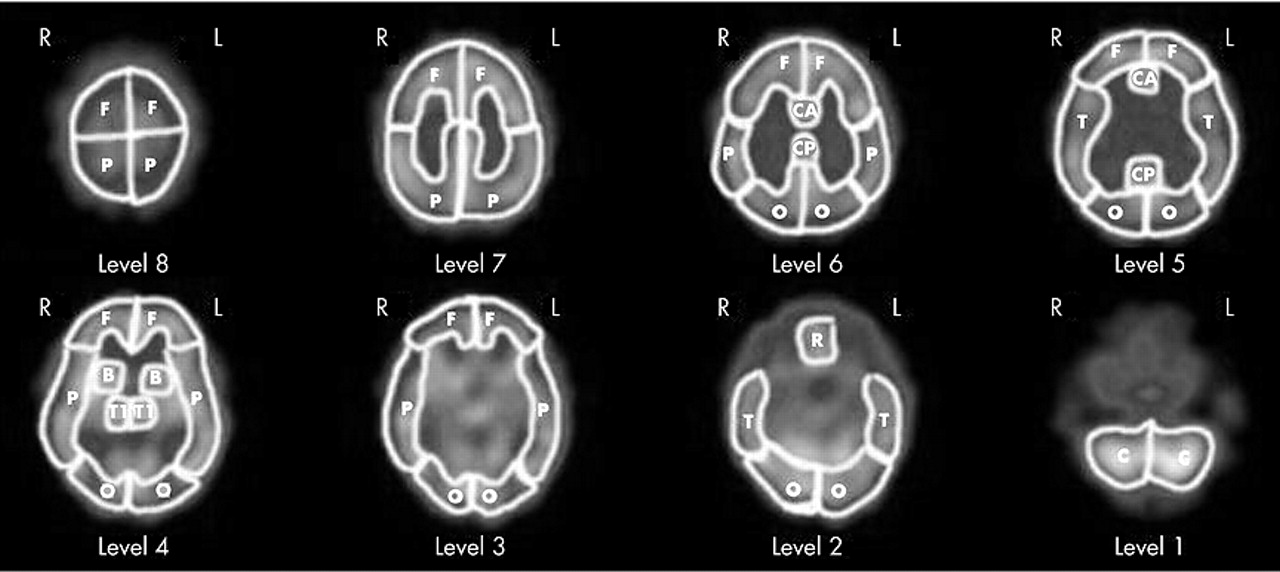

Additionally, we investigated the regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF) of both groups by technetium-99m-HexaMethyl Propylene Amine Oxime-Single photon emission computed tomography (technetium-99m-HMPAO SPECT).

DISCUSSION

Recently, it has been reported that the cognitive functions subserved by prefrontal cortex and frontocerebellar network were impaired in patients with ET.

Gasparini et al.

25 found that the group with ET and a family history of ET showed poorer performences on frontal lobe tasks involving conceptualization and set-shifting, than those of Parkinson’s disease (PD) and comparison subjects. Lombardi et al.

26 reported that impairments in working memory-attention, verbal fluency, visual confrontation naming and verbal learning and memory. Also, they demonstrated that the levels of depression of patients with ET were higher. Lacritz et al.

27 found mild cognitive impairment characterized with executive dysfunction in the subject with severe ET.

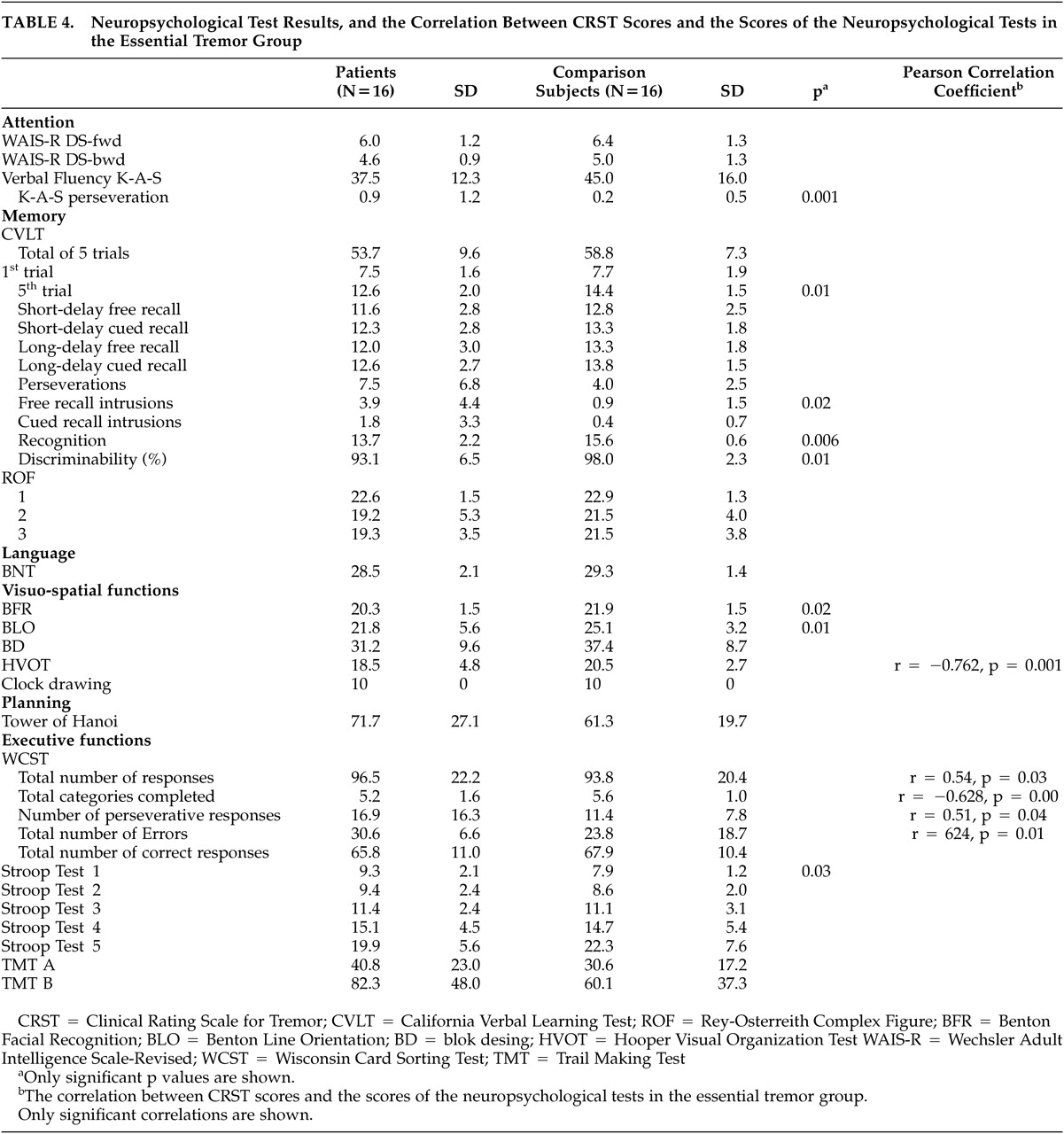

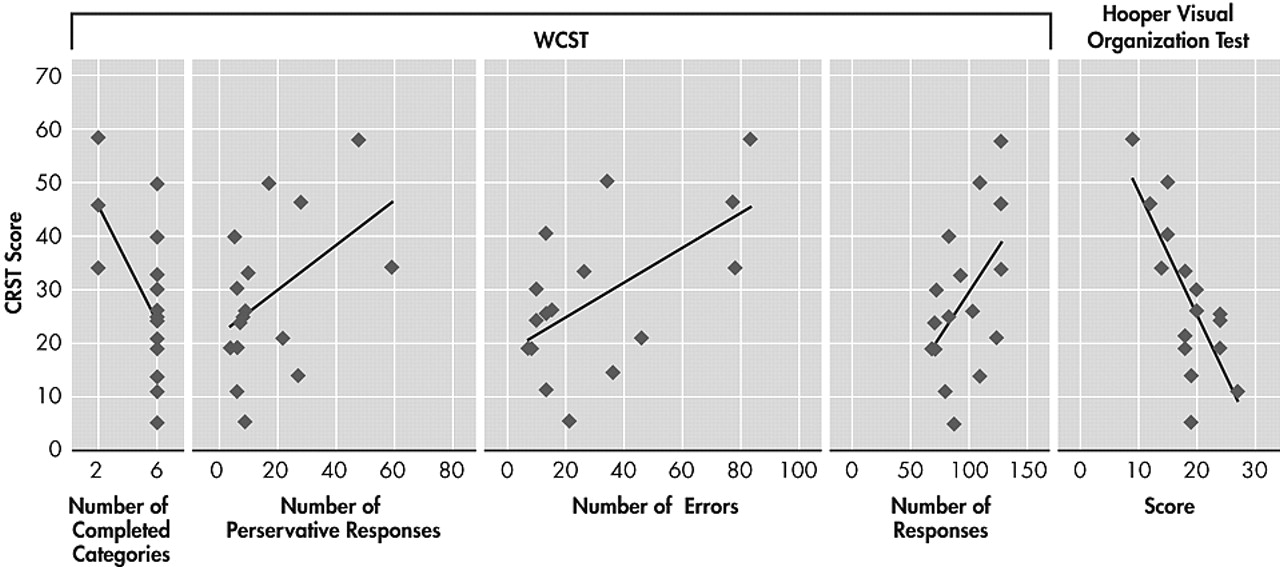

In the present study, we found significant differences between performances of the patients with ET and comparison subjects in neuropsychological tests assessing visuospatial functions and some measures of verbal memory. There were no significant differences in other tests assessing attention, visual memory, language and executive functions, except the the number of perseverations in verbal fluency, between two groups. However, we found that CRST scores of patients with ET were correlated with poorer performance on some WCST measures and HVOT.

It has been shown by clinical and experimental studies that WCST is a sensitive test of the frontal network functions such as working memory, set shifting, mental flexibility, problem solving, and conceptualization.

36,37 In our study, the total number of responses, completed categories, perseverative responses and errors on WCST in ET group were inversely correlated with tremor severity. All the studies that investigated neuropsychological functions in patients with ET demonstrated that the performance on WCST of the patients with ET is poorer than normal group or normative data. Our results are similar to those of the other studies.

According to our results, the impairments in visuospatial functions were revealed by tests requiring visual processing such as BLO, BFR, HVOT, but not requiring manipulation and construction such as block design (BD) and Hanoi tower. These findings may suggest that the poor performance in patients with ET arises from pure visuoperceptual deficits but not from a motor problem caused by tremor. Tröster et al.

28 showed that visuoperceptual abilities as measured by BFR and HVOT were significantly less than average. Lacritz et al.

27 found that the constructional abilities of patients with ET are within normal limits by BD. The posterior parietal cortex receives afferent connections from cerebellum via pons and thalamus. Visuospatial dysfunction following cerebellar damage may reflect the involvement of cerebello-ponto-thalamo-parietal pathways.

38,39 It has been known that the cerebellum plays a role in pathophysiology of ET.

4,8,9 Visuospatial disturbances in patients with ET may be due to the involvement of afferent pathways from cerebellum to posterior parietal lobe.

Although the performance of the patient group was poorer in almost all the measures of the CVLT than that of the comparison group, the differences between groups reached statistical significance on fifth learning trial, free recall intrusions, recognition hits and discriminability.

In contrast to Gasparani et al., Lombardi et al., and Lacritz et al., we did not find significant differences between ET and comparison groups in the verbal fluency.

25,26,27 However, we observed significantly higher number of perseverations on the verbal fluency in ET group. This finding is also in accordance with the hypothesis of an executive dysfunction.

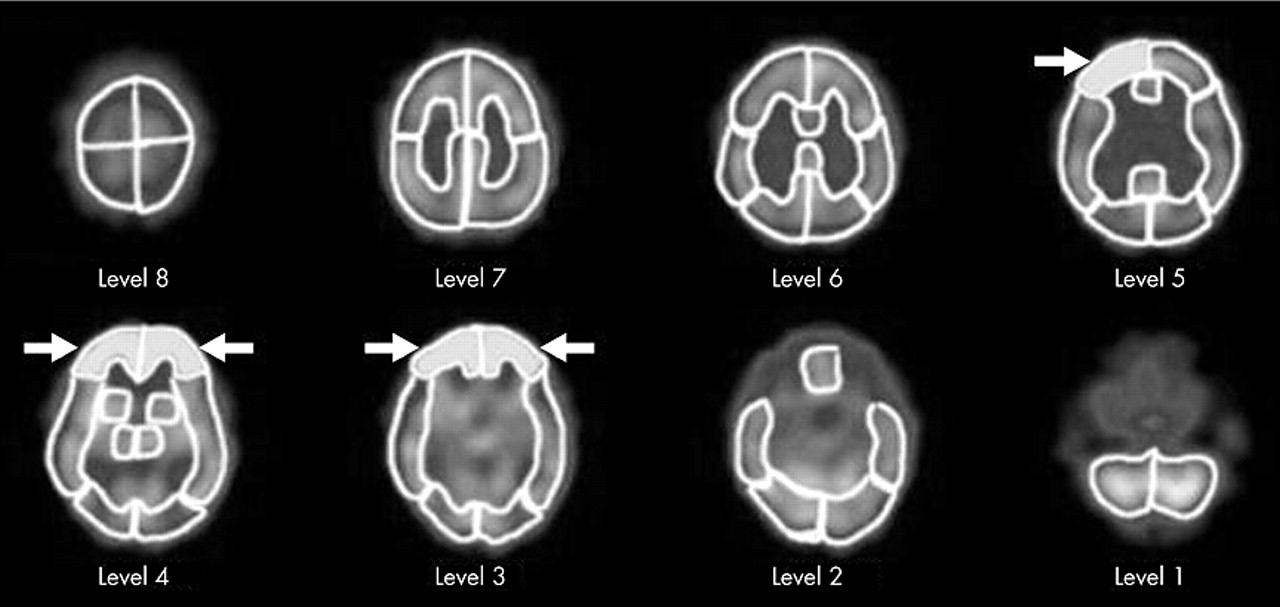

Furthermore, bilateral frontal hypoperfusion shown by SPECT scanning in the patient group correlates with both CRST scores and some of the neuropsychological test scores that are sensitive to frontal lobe functions (i.e., WCST). Higher CRST scores were associated with lower bilateral frontal blood flow. This result supports the frontal dysfunction in the patient with ET.

The results of our study, which was conducted in a relatively young sample of patients with ET, confirmed the results of the aforementioned studies that suggested a frontal network dysfunction.

The most important difference of the present study from the other three studies was the age of patients included to the study. The mean age of our cases was 29.6 years (range=18–52), whereas the mean ages of the cases in the studies of Gasparini et al., Lombardi et al., and Lacritz et al. was 68.8 years, 66.1(range=36–83), and 70 years (range=43–86), respectively.

25,26,27 Age effects on the frontal lobe functions are well known. Normal aging affects first and foremost the frontal lobes.

40,41 Thus, the confirmation of a frontal network involvement in a young patient group with ET may clarify the probable confounding age effect in the previous studies. Second, our group was comprised of nonmedicated patients that might be considered an additional advantage of the present study in terms of the confounders. Yet, relatively small sample size, especially in the SPECT component of the study could be seen as the weakness of our study. This might explain why the comparison of the rCBF’s did not reveal any differences between the two groups despite the significant inverse correlation between the ET severity and frontal rCBF in the patient group.

The present study shows that subclinical cognitive deficits, including frontal executive and visuospatial functions and verbal memory impairments, may be classified as clinical features of ET. These results support that the dysfunction of fronto-cerebellar circuits may have a role in ET pathophysiology.