H ispanics now comprise the largest ethnic minority group in the United States, and the majority of Hispanics are of Mexican descent. Forty percent of the increase in the United States’ population between 1990 and 2000 has been accounted for by its 35.3 million Hispanic residents, and the number of Hispanics in the United States aged 65 and older is expected to grow at a rate five times greater than that of non-Hispanic whites in the 21

st century.

1,

2 Yet, little is known concerning patterns of life-cycle cognitive function for this ethnic group. A few reports in the dementia research literature suggest that both the prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer’s type dementia is higher in Hispanics of Caribbean origin relative to non-Hispanic whites, but little cognitive epidemiology has been published for Mexican-Americans.

3 –

5 It is difficult to select the proper instruments for cognitive screening research among the Mexican-American population. The Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) has not been fully standardized on Mexican-American samples.

6 –

9 In addition, the MMSE correlates strongly with educational attainment, which could confer bias in studies of Mexican-American ethnicity and cognitive function.

7 –

10 Clock-drawing tests are relatively simple screening tests that access somewhat separate cognitive functional domains from the MMSE and appear less vulnerable to sociocultural influences.

11 Clock-drawing has been shown to improve the sensitivity of the MMSE to mild cognitive impairment syndromes in non-Alzheimer’s type dementias.

12 CLOXI and CLOXII tests are specific types of clock drawing tests and have separate assessments. CLOXI is sensitive to executive control function. CLOXII was designed to test constructional praxis.

13 CLOX has been translated into Spanish and validated in multiple elderly populations, including Mexican-Americans.

14 –

16 Executive control functions are cybernetic processes that control the sequencing, initiation, and monitoring of complex goal-directed activities that are mediated by the frontal lobes and their connections to other brain areas by white matter tracts.

17 CLOXI is more sensitive to executive control function than many other clock drawing tests.

14 Previous research indicates that only a small proportion of the variance in CLOX failure rates is specifically attributable to the combined effects of education, socioeconomic status, acculturation, language, and gender.

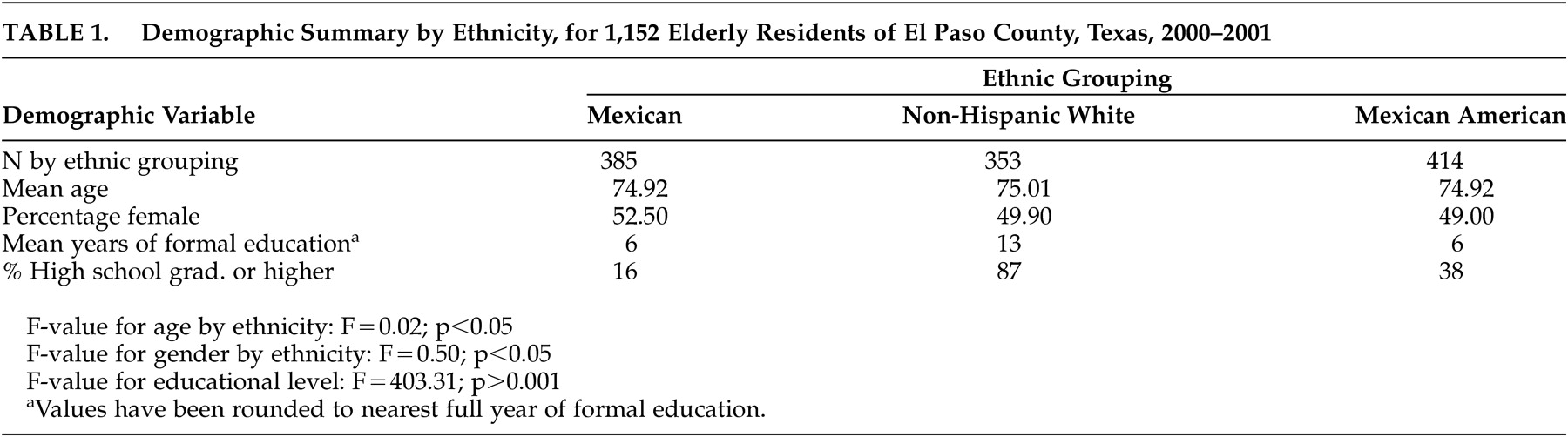

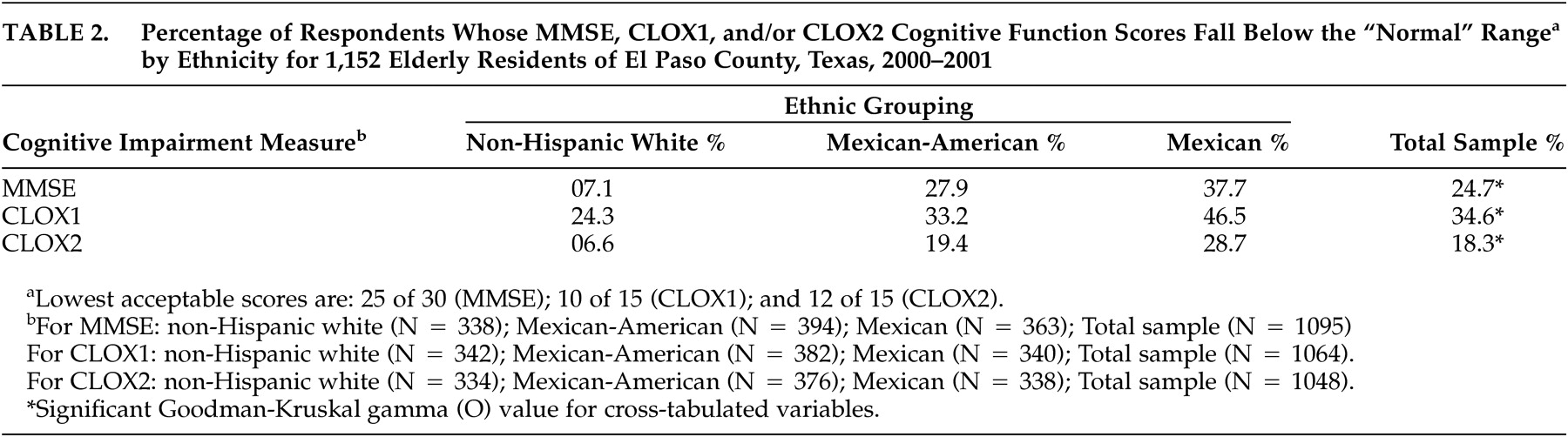

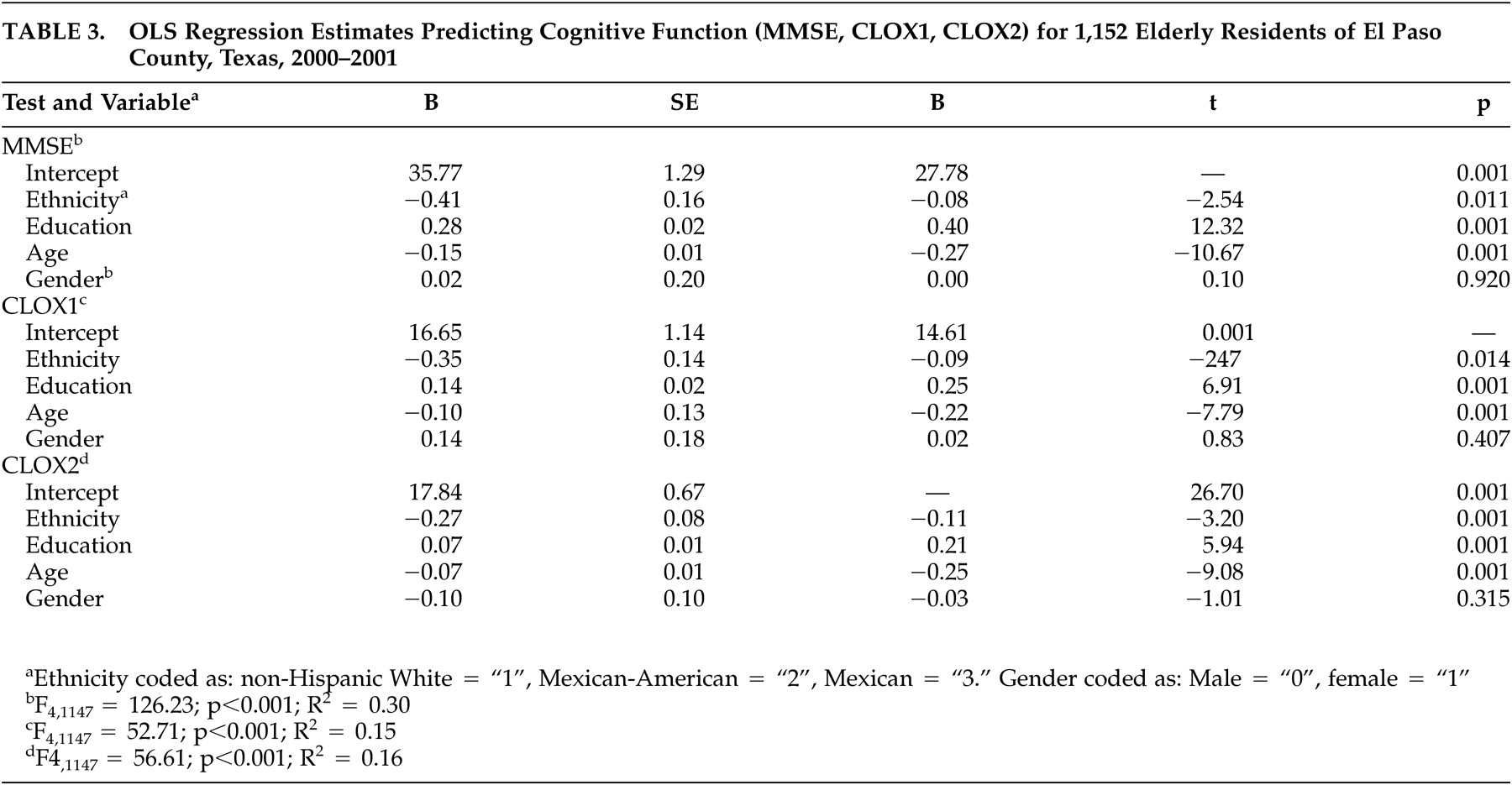

16 We designed a screening study of cognitive functions in elderly samples of noninstitutionalized Mexican-American and non-Hispanic white populations in El Paso County, Texas. We administered the MMSE, CLOXI and CLOXII to a stratified, random sample of Mexican-American and non-Hispanic whites. We sought to determine whether patterns of cognitive function in this sample are associated with education, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that in a stratified, random sample of 1,152 Mexican-American and non-Hispanic white elderly residents of El Paso County, Mexican-American ethnicity is a significant variable associated with poor cognitive functioning on a battery of screening tests. The performance impairments occur across a variety of functional cognitive domains, including domains associated with frontal/executive functions. This finding persists after controlling for effects of education, age, and gender. There is additional evidence in this study that impairment in cognitive function has negative functional implications for activities of daily life. High rates of “nondementing” cognitive impairment have previously been reported in Hispanic populations. Gurland et al.

4 reported that cognitive impairment was more common in a group of Caribbean Hispanics in New York City than among non-Hispanic whites. Most of the cognitively impaired persons in this study did not meet formal criteria for “dementia,” but were labeled “borderzone not-demented” instead. Less than half of the study population were rated free of cognitive impairment. Similar results were reported by Fitten, Ortiz, and Ponton.

24 We found that as many as 40% of 100 community-dwelling Caribbean Hispanics age 55 and older, not previously diagnosed with dementia, developed dementia over a period of 3 years. Our report from a Mexican-American data set suggests that this phenomenon of widespread, age-related poor cognitive performance is not limited to Hispanics of Caribbean ancestry.

3 –

4 From the data reported here, we cannot be sure of the neuropsychiatric determinants which underlie the finding of disproportionately poor cognitive functioning among persons of Mexican-American ethnicity. Acculturation variables alone do not seem to be the answer. Our results do not contain clinical information sufficient to allow formal diagnoses of dementia syndromes, so we do not know whether these results are driven by a high prevalence of late-life neuropsychiatric disease in this population. At this time we must say that there seem to be unspecified determinants of later life cognitive impairment in these populations, and we do not know what they are. The data are consistent with a wide range of developmental or neurobiological operating variables, and only future studies will help us understand what these variables might be. Of course, our ultimate goal will be to intervene appropriately, either with prevention or therapeutics.

In conclusion, we here report significant associations between the degree of Mexican-American ethnicity and patterns of cognitive impairment in a large El Paso sample of subjects 65 years of age and older. This pattern of cognitive impairments appears on culturally unbiased measures and is generally independent of age and educational attainment. We are not sure of the explanation for these results, and we hope to plan further studies that will help us understand them better.