M ultiple sclerosis is the most common central nervous system disease affecting young and middle-aged adults. Depression and cognitive dysfunction are common neuropsychiatric symptoms in multiple sclerosis (MS). Lifetime risk of major depressive disorder in MS is around 50%,

1 and a 12-month prevalence of major depressive disorder is approximately 25%.

2 Although cognitive impairments occur across domains, deficits in executive functioning are commonly observed in approximately 33% of patients with MS.

3 Depression and executive dysfunction co-occur in MS,

4,

5 and both may result from lesions in underlying frontosubcortical brain regions. While there is evidence supporting the role of psychosocial factors resulting from the challenges of coping with a chronic and debilitating disease,

6 demyelinating brain lesions also appear to increase risk of depression significantly.

7 –

12 Furthermore, depression is more common among patients with MS than many other chronic or neurological conditions, including spinal cord injury and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

13Executive dysfunction has been associated not only with depression, but with response to treatment. The majority of the efforts evaluating the role of executive functioning as a moderator of outcomes for depression have been conducted in the domain of pharmacological treatment in late-life depression, where deficits in executive functioning predict poor response and increased relapse rates in clinical trials evaluating conventional antidepressant treatments.

14 –

16 In addition, Potter et al.

17 found that deficits in executive functioning predicted decreased rates of remission after 3 months of treatment among patients participating in a standardized open-treatment algorithm paradigm. In the general population, deficits in executive functions predicted decreased response to fluoxetine treatment in younger, otherwise healthy individuals with major depressive disorder.

18 In sum, executive functioning appears to play a role in predicting outcomes to antidepressant pharmacological treatments.

Although the pathophysiological mechanisms in late-life depression likely differ from potential mechanisms in MS (i.e., demyelinating lesions resulting in neural dysfunction), there are similarities in the resulting frontosubcortical pathology and impairment. Not only would frontosubcortical pathology precipitate both symptoms of depression and executive dysfunction,

19 it may influence antidepressant treatment response.

20,

21 Although one study published by our group

12 observed that an association between brain lesions and treatment outcome for depression in MS was mediated by global cognitive functioning, no studies have evaluated specific cognitive markers as predictors of treatment response in MS. In addition, no studies have evaluated cognitive markers in the context of nonpharmacological treatment interventions.

The present investigation is a secondary analysis of a comparative outcome trial for the treatment of depression in MS.

22 In this investigation, we evaluated measures of neuropsychological functioning as treatment predictors across three treatments for depression. We hypothesized that performance on measures of executive functioning would predict poorer treatment response to antidepressant therapy, compared to psychosocial treatment groups.

METHOD

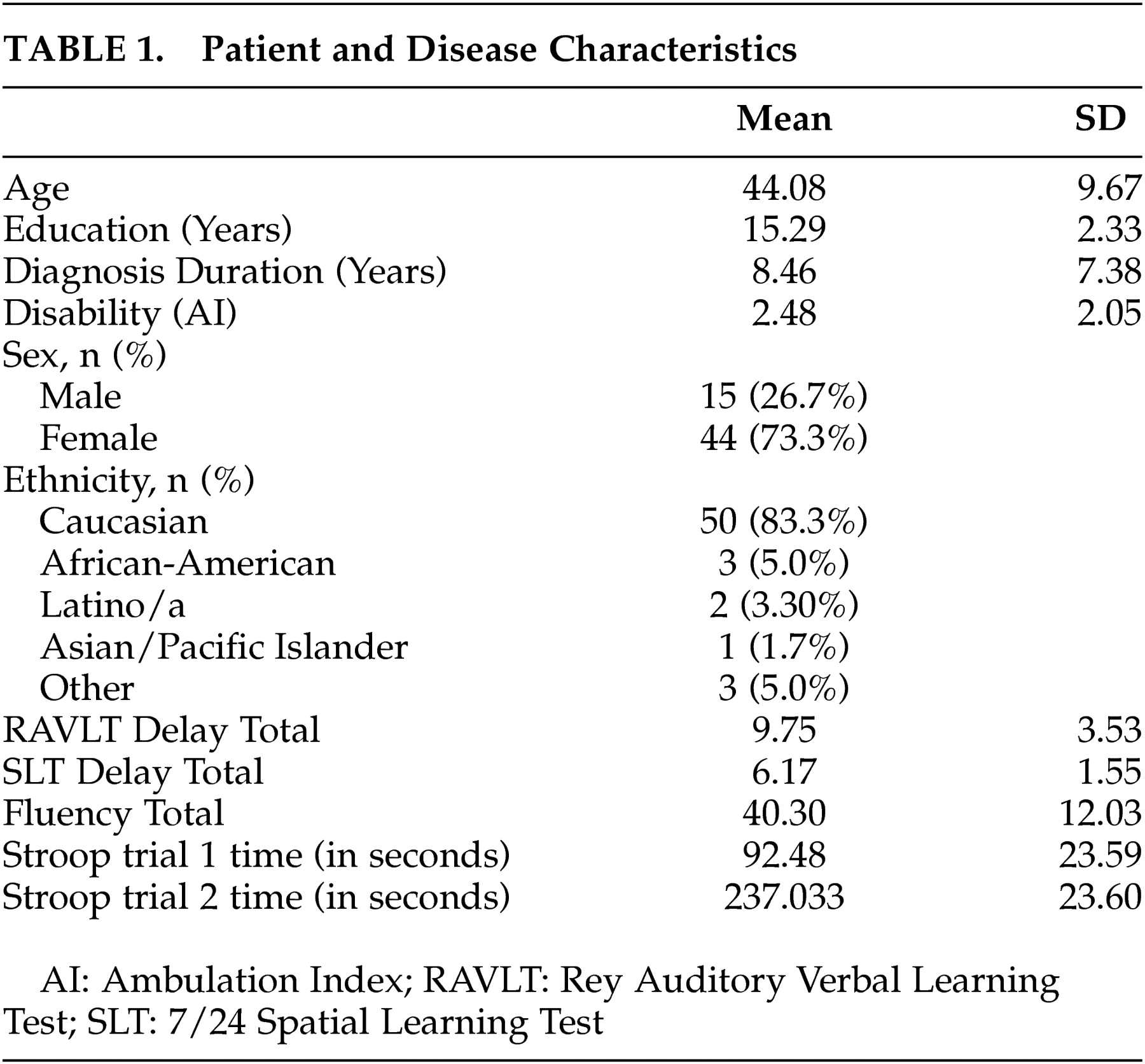

Participants

All procedures of the larger clinical trial are described in detail in Mohr et al.

22 Fifty-nine moderately depressed patients with MS participated in a clinical trial that compared three commonly used treatments for depression among medical patients. After a complete description of the study to participants, written informed consent was obtained under the guidelines of the University of California, San Francisco, Committee on Human Research.

Study participants met inclusion and exclusion criteria described below as evaluated by a study psychologist, psychometrist, and board-certified neurologist. Inclusion criteria were: a) a clinically definite diagnosis of MS using the Poser et al.

23 criteria); b) a relapsing-remitting or secondary progressive disease course confirmed by a neurologist;

23 c) a diagnosis of current major depressive disorder based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID);

24 d) a score of 16 or more on the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D);

25 e) a score of 16 or more on the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI);

26 and f) a willingness to abstain from psychological or pharmacological treatment other than that provided in the study during the treatment period.

Exclusion criteria included: a) DSM-IV Axis I psychiatric disorders, other than major depressive disorder or generalized anxiety disorder (using SCID); b) severe cognitive impairment falling below the fifth percentile in three of six areas of neuropsychological functioning (i.e., attention, concentration, speed of processing, executive functioning, verbal memory, and visual processing); c) severe suicidal ideation, plan, and/or intent; d) corticosteroid treatment within 30 days; e) initiation of treatment with an interferon medication within the previous 2 months; f) current MS exacerbation (criteria: enrollment occurred at least 3 months after onset of symptoms of exacerbation, cessation of steroid treatment for 4 weeks prior to enrollment, and patient no longer reports symptoms related to exacerbation); g) head injury or CNS disorder other than MS; h) current or planned pregnancy; i) impairment in visual acuity precluding assessment using visual neuropsychological stimuli (as evaluated by a neurologist using the Snellen visual acuity chart); and j) current psychological or pharmacological treatment for depression.

Treatments

Participants were randomized to one of three 16-week treatments for depression. This was a single-site clinical trial. After the initial screening evaluation, eligible patients who met criteria were screened again 1 to 4 weeks later. This waiting procedure served as a method of blocking patients. When accrual over a 4-week period exceeded six patients, these patients were assigned to group therapy. When accrual was less than six patients, patients were randomly assigned to either cognitive behavior therapy or sertraline. Although this procedure was not strictly random, it adequately met the need to initiate treatment within a reasonable time period and facilitate enrollment in both individual and group treatments.

Individual cognitive behavior therapy consisted of 16 weekly, 50-minute meetings between the individual and a Ph.D.-level psychologist. This treatment included standard procedures

27 and specific skills for the management of MS-related symptoms and problems (e.g., disability, fatigue management, mild cognitive impairment).

Supportive-expressive group psychotherapy is a model of group therapy for people with medical diagnoses originally developed and validated as an intervention for women with breast cancer.

28 Groups of five to nine patients and two Ph.D.-level psychologists met for 16 weekly 90-minute sessions, which focused on enhancing emotional expression, particularly related to MS, and the social and personal sequelae of the disease.

Sertraline is a commonly used antidepressant medication for MS patients.

29 Treatment was initiated at 50 mg per day. The dosage was increased by 50 mg every 4 weeks until a dosage of 200 mg was reached, or until full remission was achieved as judged by the clinicians. Medication dosage and side effects were evaluated by clinical psychologists in conjunction with neurologists. Participant visits were approximately 10 to 15 minutes every 4 weeks.

Assessment Measures

Neuropsychological Functioning

Brief neuropsychological assessments were conducted on an individual basis by trained evaluators blind to group assignment at the beginning of treatment.

Evaluators assessed memory functioning with the delayed recall trial of the Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test (RAVLT)

30 and the 7/24 Spatial Learning Test (SLT).

31They assessed executive functioning using the total number of correct answers on the verbal fluency test,

32 and the Stroop color-word test interference time from the word reading trial subtracted from the interference trial.

33 This Stroop index was created in order to control for speed of reading or articulation, and to provide a purer interference measure.

Depression

Symptoms of depression were assessed in a structured interview using the HAM-D,

25 which we used because it represents clinical assessment as opposed to self-report (i.e., the BDI). Interrater reliabilities were consistently above 0.90.

Data Analytic Strategy

Preliminary analyses examined patient characteristics as well as the presence of group differences across demographic, neuropsychological, and depression measures. Repeated measures analyses of variance (rANOVAs) were utilized to determine time (pre- versus post-treatment) by treatment (cognitive behavior therapy versus supportive-expressive group therapy versus sertraline) effects, using an intent-to-treat approach, by including participant data with at least one follow-up assessment.

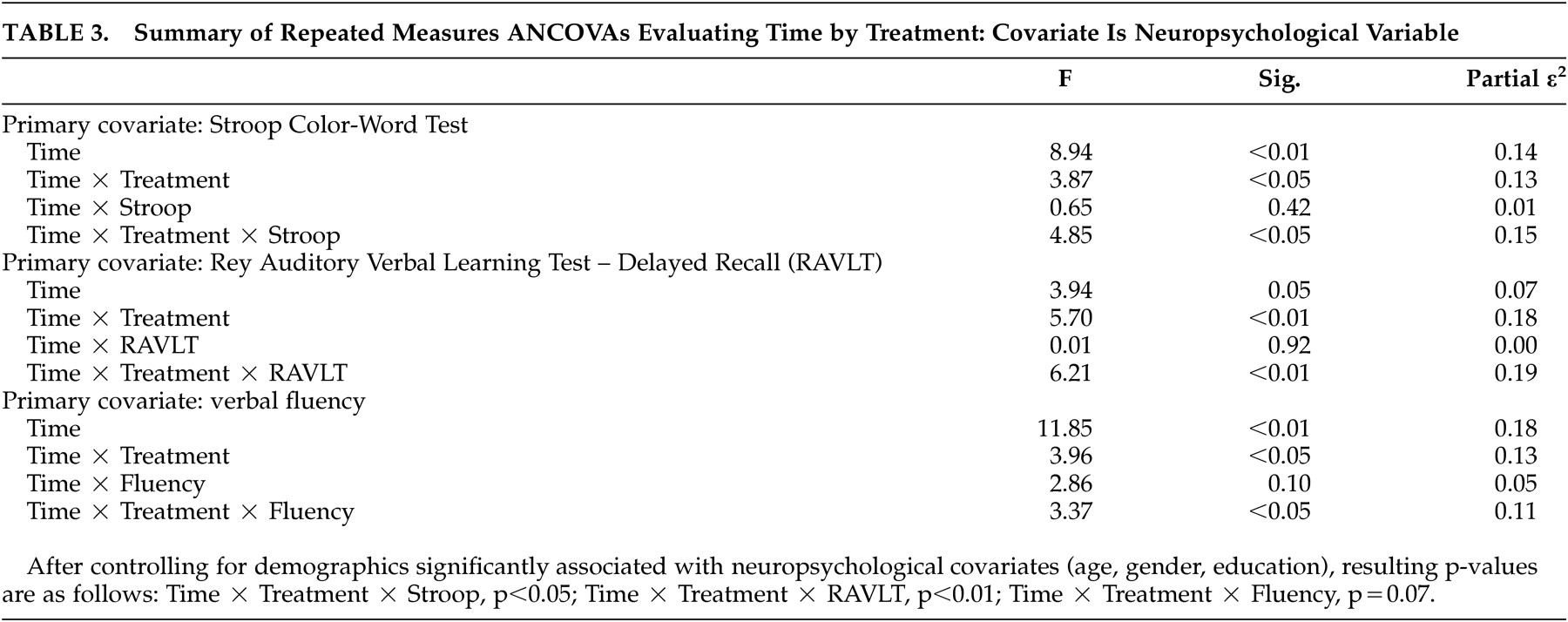

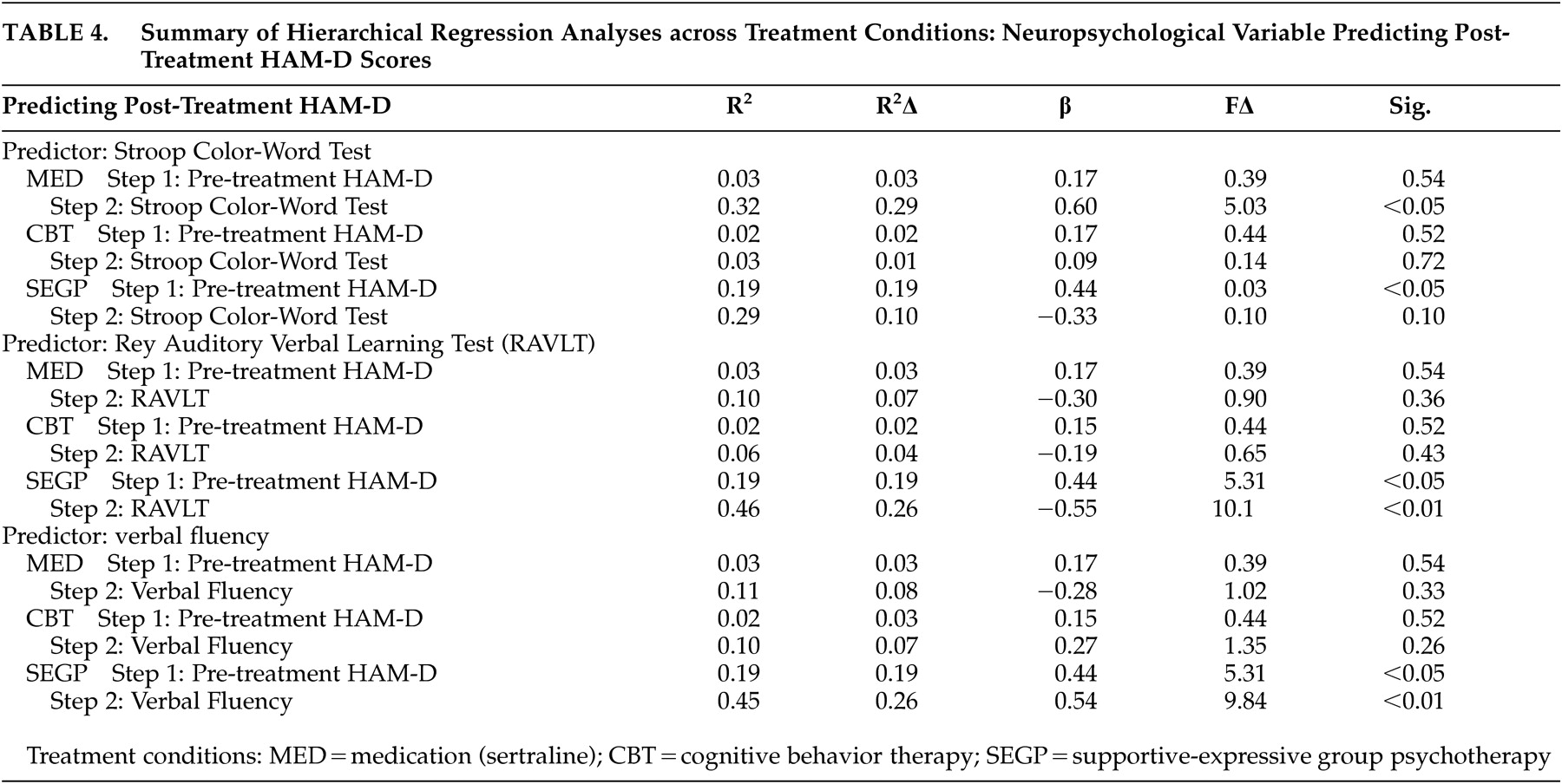

For the primary analyses, we used repeated measures analyses of covariance (rANCOVAs) with neuropsychological performance as the covariate to determine a possible time (pre- versus post-treatment) x treatment (cognitive behavior therapy versus supportive-expressive group therapy versus sertraline) x covariate (neuropsychological performance) interaction for the neuropsychological performance covariates. To explicate these interactions, we performed within-group hierarchical regression analyses using post-treatment HAM-D as the dependent variable. Pre-treatment HAM-D was entered as the first predictor, followed by those neuropsychological variables that resulted in significant rANCOVA interaction effects.

DISCUSSION

Our primary hypothesis, that performance on measures of executive functioning would predict poorer treatment response to a 16-week course of antidepressant treatment, was partially supported. This effect was specific to executive functions as measured by Stroop tasks relative to other areas of executive (verbal fluency) or other neuropsychological functioning (memory). These results suggest that there may be differential executive function predictors for treatment response, and that this effect may be specific to cognitive processes evaluated by Stroop tasks, which include response inhibition, conflict resolution, and general complex cognitive processing.

These preliminary findings are largely consistent with investigations in geriatric depression and younger patients with major depressive disorder, finding measures of executive functioning as predictors of antidepressant treatment response.

15,

16,

36 Although fluency measures using perseverative error rates also predicted reduced remission rates among patients enrolled in a standardized treatment algorithm,

17 we did not find an effect for fluency in this investigation. However, we evaluated total fluency scores in our sample and did not conduct error analyses which may prove more sensitive. A recent study evaluating a nongeriatric cohort with major depressive disorder found that performance on cognitively complex tasks predicted treatment response to antidepressant therapies.

37 Although Stroop tasks were not used in this investigation, the complex nature of the Stroop may partially explain our effect. In sum, the findings from this investigation extend previous findings by suggesting that neuropsychological deficits may be a similar prognostic indicator in other populations, such as MS. This phenomenon may be independent of specific disease state or syndrome and more strongly related to underlying neuropathology common to these disparate disorders.

Our finding that performance on the Stroop task is related to depression and treatment prognosis is hypothesis-generating regarding potential pathophysiological contributions. Dysfunction in fronto-subcortical brain regions is associated with both depressive symptoms and executive dysfunction.

38 Performance on Stroop tasks can indicate dysfunction in frontal regions, including anterior cingulate circuitry,

39 an area currently under study as a potential mediator of antidepressant response.

Imaging studies also provide clues regarding the role of the anterior cingulate in treatment response. In late-life depression, structural imaging studies found that among poor treatment responders, performance on response inhibition tasks was associated with microstructural abnormalities in the anterior cingulate.

36 Anterior cingulate dysfunction may influence treatment effects by disrupting necessary cortical-limbic functions required to facilitate response to pharmacotherapy.

20,

21 In psychotherapy, response to treatment may depend less on the integrity of the anterior cingulate, but rely on other neural systems,

40 which may explain why performance on response inhibition tasks failed to predict outcomes in our psychotherapy conditions.

Our findings that poorer performance on other executive measures (i.e., fluency) and that verbal memory predicted improved treatment response in the supportive-expressive group therapy condition is both novel and unexpected. It is possible that this finding is unique to our sample; however, the consistency across measures suggests that this effect on psychotherapy outcomes is worthy of further study. As a result of cognitive deficits, these patients may be particularly responsive to emotional support available in group treatments as compared to conceptually difficult treatment strategies (e.g., cognitive interventions). The group treatment relied upon emotional expression and social support as the vehicle for change.

28 We also speculate that the greater improvement among patients with cognitive deficits is rooted in the social consequences of these impairments. As cognitive dysfunction increases among MS patients, social support deteriorates.

31 Therefore, a treatment providing social support can significantly improve well-being for cognitively impaired patients without adequate support.

41 This argument may also apply to the medication treatment group, as they received far less social contact than the group treatment condition. Therefore, the role of social support in mediating treatment response in patients with cognitive impairments deserves further investigation.

There are several limitations to this study. First, the sample sizes are small, and further investigations replicating these preliminary findings are warranted. An additional limitation is the “post-hoc” nature of this investigation. Prospective investigations of cognitive predictors of depression treatments in MS are necessary. In addition, we were unable to fully characterize depressive disorders in our cohort, including data on family history and onset of depressive disorder in relation to onset of MS. Frontosubcortical structural alterations are associated with MS lesions, but also with familial major depression.

42 These structural changes may precipitate and predispose patients to developing depressive disorders, and may influence response to antidepressant medications.

43,

44 Future studies better characterizing depressive disorders in MS will help to elucidate etiological factors and predictors of treatment response among MS patients with depression.

To our knowledge, this is the first investigation evaluating depression and neuropsychological predictors of depression treatment outcomes in MS. We hypothesize that both depression and the executive dysfuction may be precipitated by an underlying brain dysfunction contributing to poor antidepressant response. The relationship among executive dysfunction and antidepressant effects in MS needs to be studied prospectively, along with further evaluation of specific brain regions associated with executive functioning, depression, and treatment, in order to clarify these hypothesized brain-behavior relationships.