P osttraumatic stress disorder is one of several psychiatric disorders that may increase suffering and disability among people with traumatic brain injury (TBI).

1,

2 As many as 17% to 30% of people with traumatic brain injury (TBI) meet DSM-IV

3 criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

4 –

6 PTSD has been studied more extensively among people with mild TBI; however, PTSD has also been documented among people with moderate to severe TBI where there is definite loss of consciousness and little or no conscious memory of the event.

7,

8 It has been hypothesized that PTSD symptoms can be mediated by classically conditioned fear responses or other nondeclarative memory mechanisms.

9 Among those with moderate to severe TBI, the prevalence of PTSD varies widely and the validity of the diagnosis remains controversial.

10 Bryant et al.

4 reported that among 96 patients with severe TBI, 27% met DSM-III-R criteria for PTSD 6 months after injury. In contrast, three smaller studies of more severe TBI found PTSD to be infrequent

8 or absent in their samples.

11,

12Research in this area has been limited by modest sample sizes and the use of clinical, referral, or survey samples that may be biased toward a greater psychopathology.

10 Several studies assessed PTSD symptoms at irregular periods and over a wide range of time post-injury. Studies have not assessed the potential impact of overlapping PTSD and TBI symptoms on PTSD prevalence rates. Information on psychiatric vulnerability or comorbidity has been absent or very limited.

For the present study, we examined the rates of PTSD symptoms during the first 6 months after injury in consecutive patients hospitalized with complicated-mild to severe TBI. Our primary research questions were: 1) What is the incidence, prevalence and natural history of meeting DSM-IV PTSD symptom criteria in this population? 2) Do factors found to be predictive of PTSD in other patient populations increase the risk of meeting PTSD symptom criteria in this population? These theoretical predictors include: female gender,

13,

14 little education,

15,

16 history of anxiety or depression,

17 less severe brain injury,

7,

8 being assaulted,

13 strong emotional reactions to the incident,

18 and being under the influence of stimulant drugs.

14 3) To what extent is meeting symptom criteria for PTSD associated with other current or past psychiatric disorders? 4) Are PTSD symptoms associated with significant psychosocial impairments or poor subjective health?

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics and Symptom Endorsement

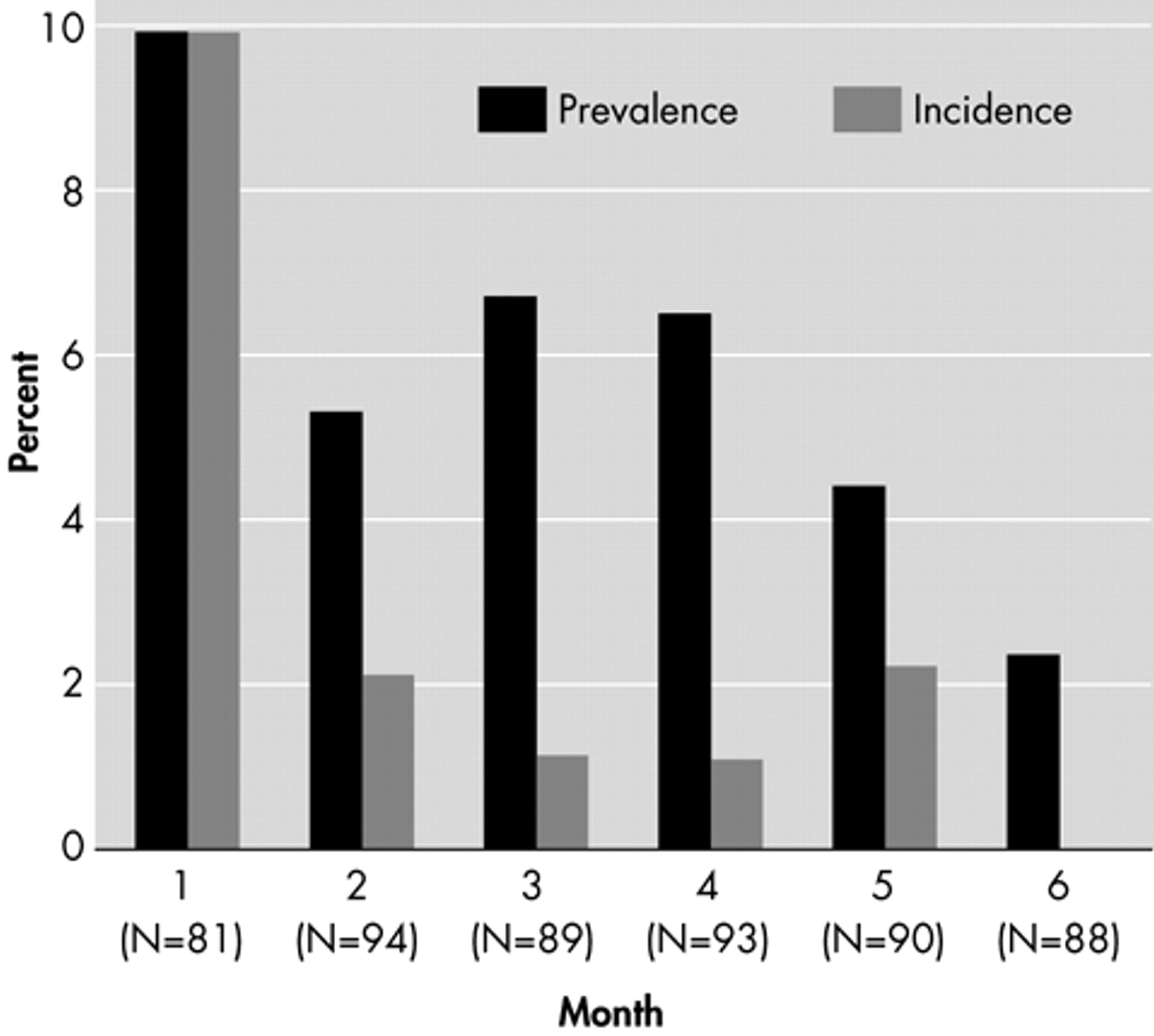

During the period from May 25, 2001, to January 1, 2003, we identified 211 eligible cases among consecutive admissions. Of these, 41 declined consent, 18 verbally consented but did not return the signed consent form, seven withdrew their consent, two never passed the orientation assessment and two could not be contacted. Of the 141 who consented, 16 did not complete the PCL-C. A total of 125 subjects were assessed at least once during the 6-month period. The number assessed at each time point is displayed at the bottom of

Figure 1 . Of the 125 subjects, 14 subjects only had one assessment and this occurred at the first month in six of these subjects.

Subjects were on average 43 years old (SD=18.6), 77% were male and 92% were Caucasian, while 6% were African-American and 2% were Asian-American. Forty-three percent of the sample was married and 85% had completed high school or earned a GED. The most common mechanism of injury was a moving vehicle accident (49%), followed by falls (32%), assault (7%), and other (12%). Based on GCS scores, 44% of brain injuries were complicated-mild, 30% were moderate, and 27% were severe. Ten percent of the sample had a positive toxicology screen for amphetamines or cocaine. Subjects did not differ significantly from the group that was eligible but not enrolled on any of the demographic or injury-related variables.

Incidence, Prevalence, and Natural History of PTSD Symptoms

The incidence and prevalence of patients who met PTSD symptom criteria each month are displayed in

Figure 1 . Overall, 14 cases (11.3%) of the total sample met PTSD symptom criteria some time during the first 6 months. The overall trend was toward decreased prevalence over time, suggesting a relatively short duration of PTSD. Ten of 14 subjects (71.4%) who met PTSD symptom criteria also met Criterion F, that is, reported that these symptoms made it at least somewhat difficult for them to function at work or home, or to get along with people. Only seven subjects (5.6%) met all self-reported aspects of DSM-IV criteria (A2, B, C, D and F).

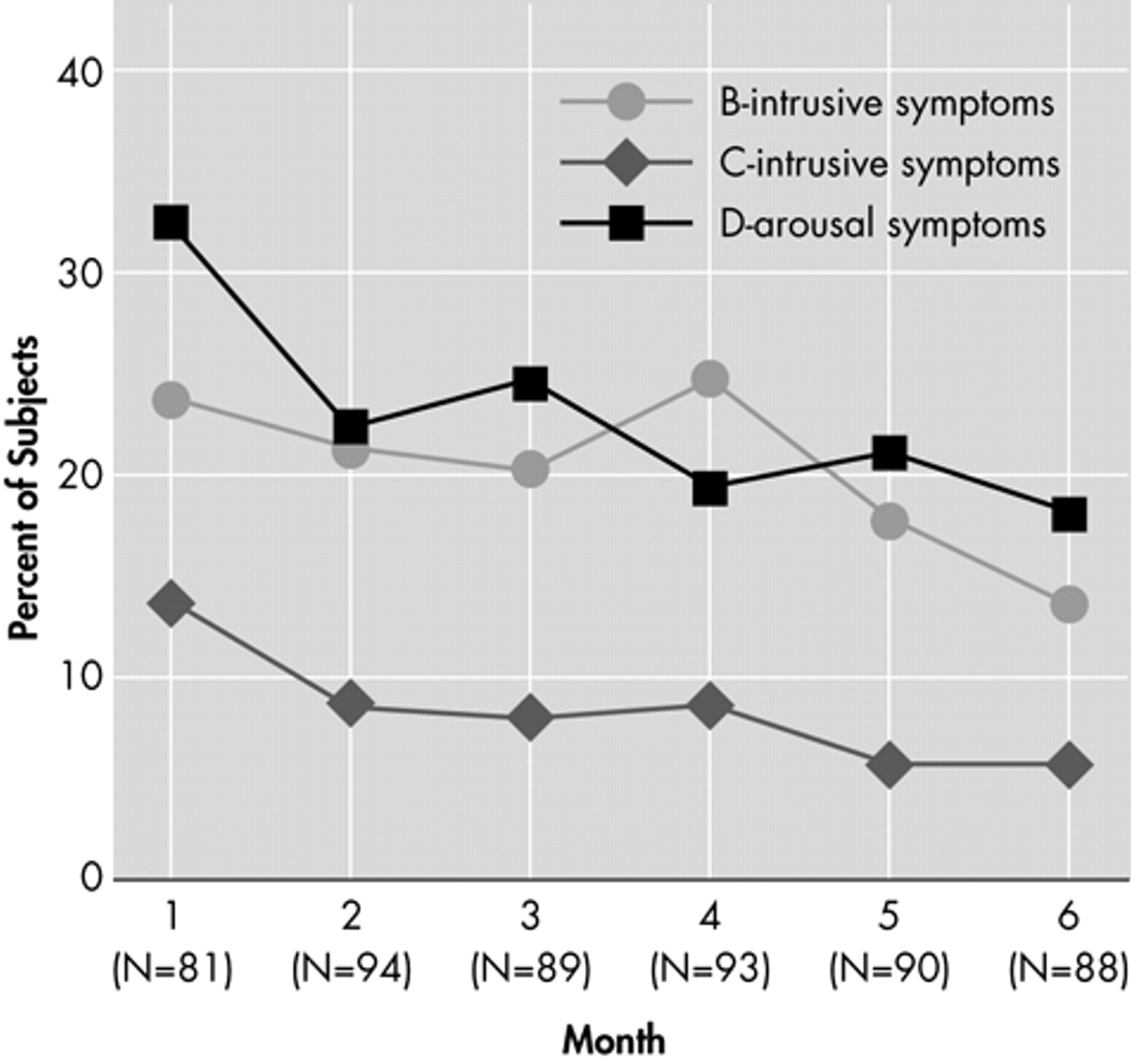

Figure 2 shows the proportion of subjects that met PTSD B, C, and D criteria over the 6-month period. Intrusive and arousal symptoms were more prominent relative to avoidant symptoms. This graph also demonstrates the downward trend in all three symptom domains over time. The proportion of the total sample that met the A2 criteria (recalled feeling helpless or terrified) when asked during their first monthly interview was 12.1%.

As described above, we wanted to compare three ways of scoring amnesia for important parts of the traumatic event. The lower bound estimate (coding Item J as missing when there was no recall) was the basis for the data already reported. The upper and intermediate bound estimates resulted in 18 (14.5%) and 14 (11.3%) cases, respectively, meeting PTSD symptom criteria over 6 months.

Predictors of PTSD Symptoms

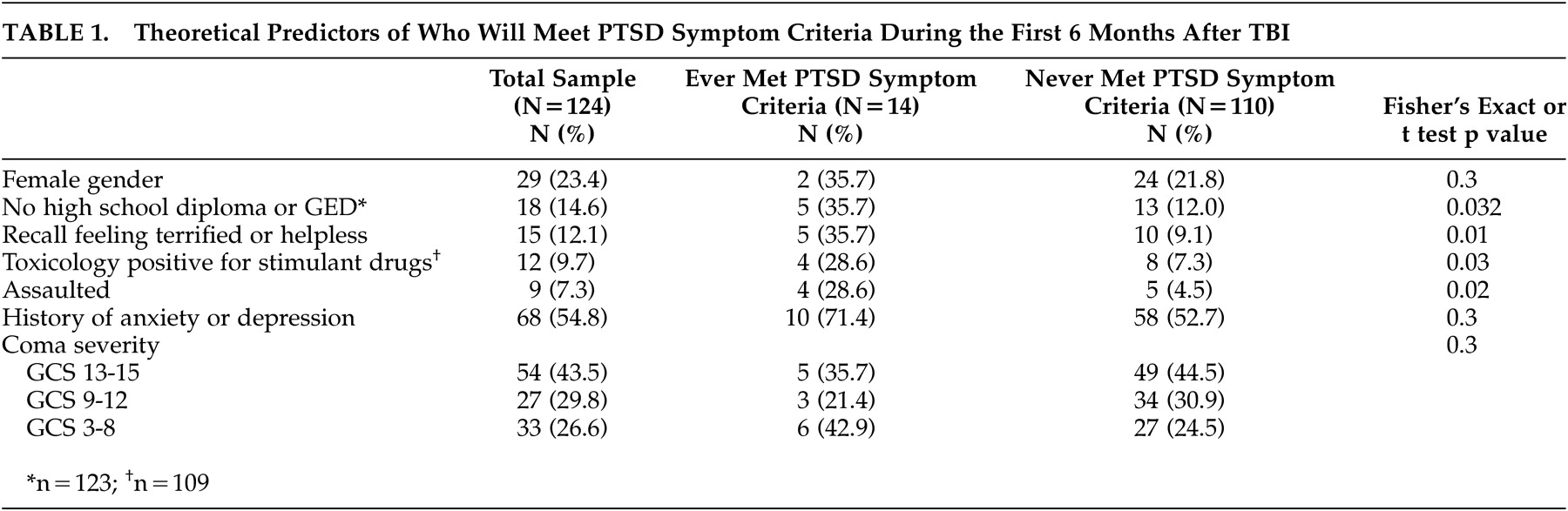

The relationship of theoretical predictor variables to the development of PTSD symptoms is reported in

Table 1 . A low level of education and several injury-related factors were associated with increased risk of PTSD symptoms. Coma severity was not related to PTSD symptom criteria.

Psychiatric Comorbidity

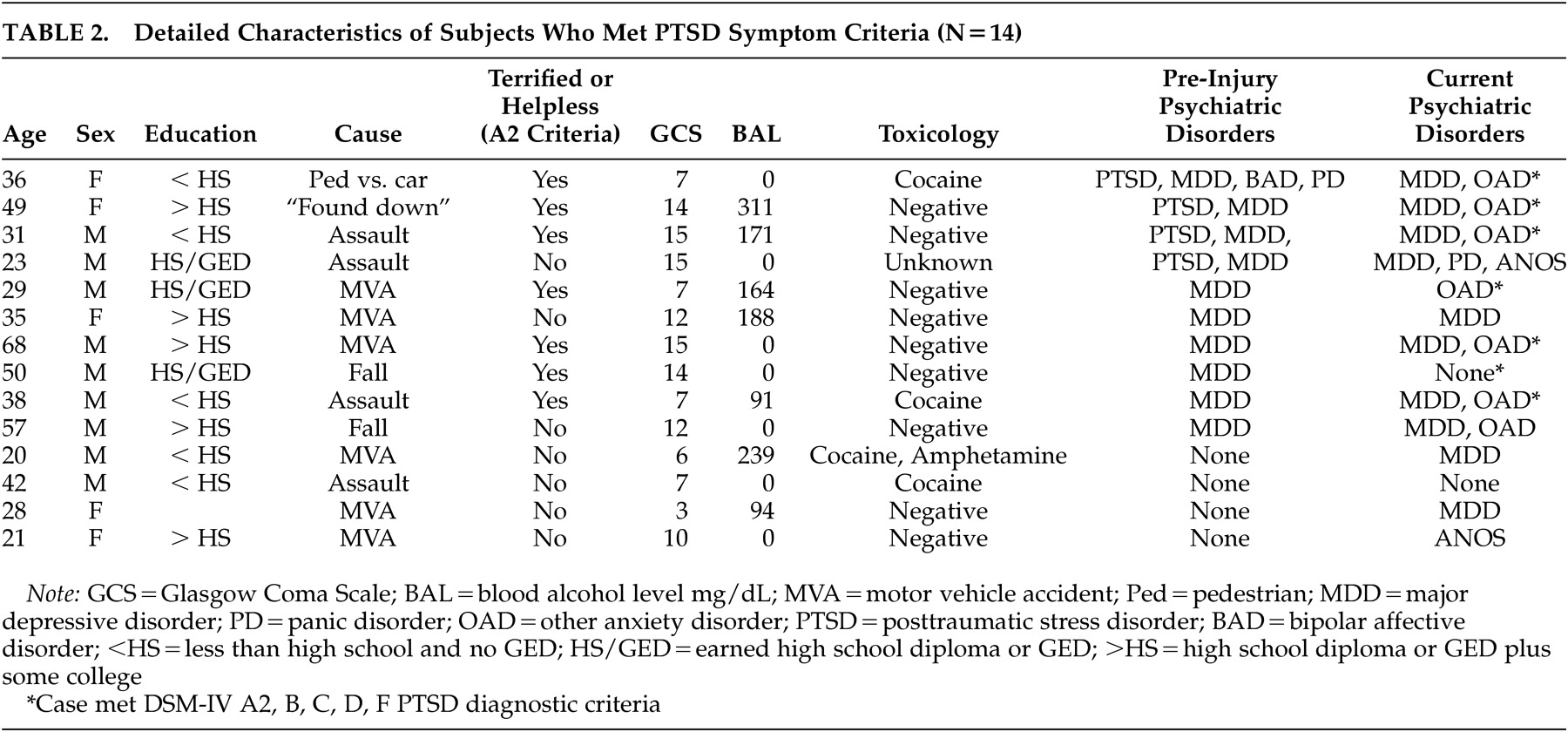

Twelve of 14 cases (85.7%) that met PTSD symptom criteria also reported symptoms of at least one other current psychiatric disorder. Compared to the remainder of the sample, those who met PTSD symptom criteria were significantly more likely to meet criteria for current major depressive disorder (71.4% versus 15.5%; Fisher’s Exact p<0.001), panic disorder (21.4% versus 4.5%; Fisher’s Exact p=0.046) and other anxiety disorders (71.4% versus 18.2%; Fisher’s Exact p<0.001).

Ten cases met criteria for at least one pre-injury psychiatric disorder, but only a history of PTSD was significantly associated with meeting symptom criteria for PTSD (28.6% versus 1.9%; Fisher’s Exact p=0.001). Demographic, risk, and comorbidity data are displayed in

Table 2 for all cases that met PTSD symptom criteria.

Relationship to Subjective Health and Functioning

The odds of reporting that PTSD symptoms made it very or extremely difficult to function at home, work, or with people were significantly higher (OR = 1.28; 95% CI: [1.02, 1.61] p=0.036) among those who met PTSD symptom criteria versus those with less severe symptoms. There was a nonsignificant trend toward reporting subjective health as only fair or poor in those who met PTSD symptom criteria versus those who did not meet these criteria (OR = 1.34; 95% CI [0.99, 1.81] p=0.055).

DISCUSSION

The cumulative incidence of those meeting PTSD symptom criteria was 11.3% in a representative sample of people with complicated mild to severe TBI during the first 6 months following injury. These data suggest that PTSD is less common than the 27% prevalence rate reported by Bryant et al.,

4 possibly because we recruited an unselected sample while Bryant et al. studied a referral sample, almost all of which was involved in litigation. Our data also diverge from two smaller studies that detected no cases that met full symptom criteria for PTSD among people with moderate to severe TBI.

11,

12Though the present data confirm that people with moderate to severe TBI can develop the entire constellation of PTSD symptoms, only seven (5.6%) of our sample met DSM-IV A2, B, C, D and F criteria. Moreover, prevalence data over the 6-month period suggest an attenuation of symptoms over time in all three symptom clusters.

These data are consistent with the idea that more severe TBI may be protective with regard to the development of PTSD. For example the incidence of DSM-IV PTSD during the first 6 months after motor vehicle crash, excluding people with TBI, is at least 34% in two independent studies.

18,

33 Prospective cohort studies of injury survivors with versus without TBI are needed to more rigorously evaluate the protective hypothesis.

Caution is needed when diagnosing PTSD among people with significant TBI. As an example, estimates of PTSD may be inflated if brain injury-induced amnesia is equated with PTSD-related psychogenic amnesia or dissociation. Recent reviews have noted that overlapping symptoms as well as pain, medications, peri-traumatic experiences, self-selected or referral subject samples, and comorbid psychiatric disorders, can all complicate the diagnosis and prevalence estimates of PTSD in TBI and other injured populations.

10,

34Several factors seem to increase the risk of developing significant PTSD symptoms. People with less than a high school education were at higher risk than those with more education. We have reported similar findings with regard to risk of depression in an independent sample.

35 Nevertheless, it should be noted that those with low education were also likely to have had one or more of the other significant risk factors and, as in the National Comorbidity Study,

13 the relationship between education and PTSD may not remain after controlling for other risk variables. Those who recall feeling terrified or helpless were more likely to meet PTSD symptom criteria over the 6-month period,

36 and consistent with epidemiological studies of PTSD,

13 being assaulted was also associated with an increased risk of meeting PTSD symptom criteria relative to other types of trauma. Finally, those who had used stimulant drugs (cocaine or amphetamine) around the time of injury were more likely to meet PTSD symptom criteria. Cocaine intensifies fear conditioning in animals

37 and enhances or extends amygdala functioning in humans, resulting in traumatic memories being more easily triggered or recalled.

38 This risk factor merits further study because specific therapies may attenuate cocaine-induced fear sensitization.

39In our sample, meeting PTSD symptom criteria was significantly related to greater psychosocial impairment but not poorer subjective health. It should be noted that we used a rather blunt single question measure of health. Larger studies are needed that use more sensitive measures of health-related quality of life to adequately assess the impact of PTSD symptoms on this important outcome.

These results emphasize the importance of assessing other past and current psychiatric disorders when studying and treating PTSD and TBI. Twenty-nine percent of cases that met PTSD symptom criteria reported a pre-injury history of PTSD diagnosis. Consequently, PTSD symptoms reported after TBI frequently may reflect a continuation or exacerbation of a previous psychiatric illness in this population. Next, it is striking that symptoms consistent with major depressive disorder were present in 79% of the subjects who met symptom criteria for PTSD. Major depressive disorder is thought to amplify a variety of other aversive physical and psychological symptoms in people with TBI

40 or other medical conditions.

41 Major depression may play a role in elevating the risk of developing PTSD via this mechanism. Finally, the comorbidity of PTSD with other anxiety and panic disorders suggests there may be a generalized vulnerability to anxiety-related symptoms following TBI.

A number of limitations of the study should be discussed. The study was conducted at a single site consisting of mostly Caucasian men with complicated-mild to severe TBI. Our findings may not be generalizable to less severe injuries, women, or ethnic minorities. Although the PCL-C has demonstrated good diagnostic sensitivity and specificity in other populations

24,

25,

42 and we documented excellent interrater reliability, the question remains whether completing the measure with a telephone interview may have over- or underestimated the incidence of PTSD compared with a face-to-face administration of the measure or an in-person structured diagnostic assessment. The PCL-C administered as a telephone interview has been utilized in other populations.

43 In addition, even though the subjects had to pass a basic orientation test prior to participating, underlying cognitive impairments in subjects with more severe injuries may have altered the reliability of the responses on the telephone interview. Our measurement of other current and past psychiatric disorders has similar limitations in that our estimates are based on screening measures and not structured diagnostic assessments. Finally, we explored a relatively large number of a priori predictor variables with a sample size that precluded multivariate analyses of these potentially interrelated risk factors. Although each predictor was derived from the preexisting empirical literature, our findings should be considered preliminary until replicated.

This study highlights the complexity of studying PTSD in persons with TBI and how PTSD should be studied in the context of other demographic, injury related, psychiatric, and substance use-related vulnerabilities. While PTSD is not common in the range of brain injury severity investigated in this study, clinicians should remain alert to the possibility of PTSD following TBI in vulnerable individuals and assess the entire constellation of pre- and post-injury risk factors and psychiatric comorbidities that may increase the risk for PTSD symptoms. Finally, affected individuals should be directed toward effective treatment to reduce the magnitude of disabilities following TBI.

44,

45Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R0-1 HD39415 from the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH. Data from this paper were presented at the 51 st annual meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, Ft. Myers, Fla., November 2004.

We are grateful to Jason Barber for database management and data analysis, and to Audrey Jones, Carina Morningstar, Holly Rau, and Heather Romero for data gathering, data entry, and quality control.