A large and rapidly growing literature in magnetic resonance imaging has shown that several regional brain volumes differ between schizophrenia patients and healthy comparison subjects.

1 Many of these studies have found that regional parenchymal volumes, such as medial temporal and inferior parietal regions, are larger in healthy subjects than in schizophrenia patients. However, the reverse is also found, especially in the basal ganglia.

The meaning of larger regional brain volumes in schizophrenia is unclear. Larger volumes in patients may reflect larger numbers of neurons, increased neuronal size, reduced neuronal density with an equivalent number of neurons, edema, or other pathological processes.

However, no prior study addresses the specific relationship between caudate volumes and aggression in treatment-resistant schizophrenia patients. Given the findings described above, variations in caudate volumes might have implications for the pathophysiology of aggression. We chose to examine these relationships in exploratory analyses.

RESULTS

As noted above, 43% of patients had at least one aggressive incident during the 14-week study period. The subjects had a mean TAS score of 6.83 (SD=17.6), a mean PANSS Impulse Control score of 1.67 (SD=1.04), and a mean PANSS Hostility score of 2.05 (SD=1.28).

Patients had a mean brain volume of 1,204.04 (SD=113.88) cc, with a mean white matter volume of 429.25 (SD=39.7) cc, a mean gray matter volume of 608.2 (SD=62.6) cc, and a mean CSF volume of 167.5 (SD=27.8) cc. Patients had a left caudate volume of 4.0 (SD=0.6) cc, a right caudate volume of 4.2 (SD=0.6) cc, and a total caudate volume of 8.2 (SD=1.1) cc.

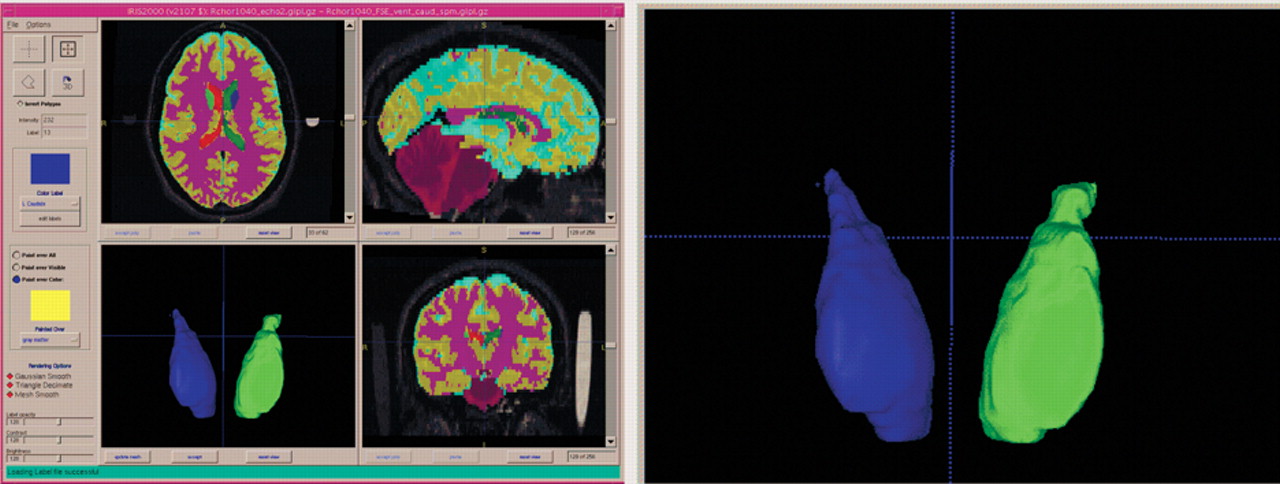

Relationships between caudate volumes and aggression are shown in

Table 1 . Larger left caudate volumes were associated with higher TAS scores during the study period. Moreover, regarding the incident status, patients who had any aggressive incident had larger caudate volumes than did those who had no such incidents. This pattern seemed particularly prevalent on the left. Finally, left caudate volumes were larger in patients with lesser degrees of impulse control, with a similar trend for total caudate volumes.

Left caudate volumes were inversely correlated with age (r=−0.30, p=0.04). However, caudate volumes did not correlate significantly with the duration of illness. Finally, controlling for age and intracranial volume, ESRS scores did not correlate with caudate volumes.

We conducted additional analyses with gender, substance use disorder, and alcohol use disorder as covariates. The results using these covariates were essentially unchanged from those discussed above.

DISCUSSION

The primary finding of this study was that larger caudate volumes were associated with aggressive behavior. These results were independent of effects due to age, alcohol use disorders, or substance use disorders.

Previous work suggested that treatment with typical antipsychotic drugs increases caudate volumes. Basal ganglia volumes are increased in patients with schizophrenia in vivo (using MRI)

21,

22 and post-mortem.

23 This increase may vary with treatment history. Schizophrenia patients who had been treated with typical antipsychotic drugs showed increases in the volume of the caudate.

24,

25 In a post-mortem study in rats, chronic treatment with haloperidol was associated with increased striatal volumes.

26 Thus, the effect of haloperidol on striatal volumes in patients may be related to treatment rather than to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia. In further support of this argument, when patients were switched to clozapine, an atypical antipsychotic drug, caudate volumes were reduced.

27,

28 Interestingly, clozapine has well-known antiaggressive effects in schizophrenia.

3,

29The duration of typical antipsychotic drug treatment may be related to increases in volume of the basal ganglia,

30 suggesting that the effects of such treatment may be cumulative. However, in the current study, duration of illness did not account for the relationships between caudate and ventricular volumes and outcome. It is possible that long-term treatment with typical antipsychotic drugs had a nonlinear relationship with the volume increase we measured. The effects may plateau after a certain period of exposure to typical neuroleptics, with no further progression.

The mean duration of patients’ treatment with typical antipsychotic drugs (estimated by the time elapsed since first hospitalization) was 18.6 years. Treatment resistance to antipsychotic drugs was an eligibility criterion for participation in this study. In the past, treatment resistant patients, particularly those showing persistent aggressive behavior, were treated with ever increasing doses of typical antipsychotic drugs. Clinically unsuccessful as it was, such high-dose treatment may have resulted in cumulative effects on the caudate. Thus, the relation between caudate size and aggression we observed could have arisen as an epiphenomenon: patients failed to respond, were aggressive, therefore received high-dose long-term treatment with antipsychotic drugs, and that treatment coincidentally resulted in caudate volume increase. If this was true, the caudate volume increase was a consequence (rather than an antecedent) of aggression, and it was mediated by treatment with antipsychotic drugs.

However, this iatrogenic mechanism may not fully explain the observed relation between caudate size and aggression. Long-term treatment of nonresponding aggressive patients is not necessary for a caudate volume increase: the caudate volume was reported to increase early in the first year of treatment even in first-episode patients responding to pharmacotherapy.

24 Consistent with that observation,

24 an increase in striatal blood flow was reported in first-episode, neuroleptic-naïve schizophrenia patients after the initiation of pharmacotherapy.

31 Our lack of finding a significant relationship between caudate volume increase and duration of illness also points to other contributing factors. Striatal blood flow may be related to antipsychotic

31 treatment as well as to aggression.

9Caudate dysfunction, perhaps independently of its origin (pharmacological or otherwise), may interfere with the normal functioning of the frontal-subcortical circuitry. Cummings

5 proposed a prefrontal-subcortical circuit, including the caudate, corresponding to the orbitofrontal lobe neurobehavioral syndromes. Empirical observations indicate that penetrating brain wounds causing frontal medial lesions were associated with more aggressive behavior than lesions to other brain areas.

32 Consistent with these ideas, Hoptman et al.

33,

34 found significant negative correlations between white matter integrity, as measured using diffusion tensor imaging, and both impulsivity and aggression in a variety of areas, including the caudate. Because white matter tracts play an important role in the connectivity of the brain, the disruptions of white matter integrity in the regions mentioned may well have implications for the orbitofrontal syndrome.

The current findings have implications for the interpretation of studies in which the relationship between functional outcome and brain volumes is studied. Thus, for volumetric studies of schizophrenia, it is important to know the patients’ treatment history.

The study has some important limitations. The subjects who received the MRI may not be representative of treatment-resistant schizophrenia patients, or even of the small sample from which they were selected. In addition, the sample was not specifically sampled for a high rate of aggressive incidents. Finally, we did not have information on head injury or criminal history in these patients.

In conclusion, in this sample of patients with treatment-resistant schizophrenia, larger caudate volumes were associated with aggression. This association may be due to treatment with antipsychotic drug, to the pathophysiology of schizophrenia, or to a combination of these two mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIMH grant (R10 MH53550). Additional support was provided by the UNC-Mental Health and Neuroscience Clinical Research Center (MH MH33127). The authors also acknowledge the Stanley Medical Research Institute, Grant # 01-109, for supporting the development of improved methods and application to this clinical study. The authors thank Janssen Pharmaceutica Research Foundation, Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, and Merck and Co., Inc., for their generous gifts of medications. Eli Lilly and Company contributed supplemental funding. However, overall experimental design, data acquisition, statistical analyses, and interpretation of the results were implemented without any input from any of the pharmaceutical companies. MJH received additional support from R01 MH064783 and from a NARSAD Young Investigator Award. JAL is now the Director of New York State Psychiatric Institute, NY, NY and Chairman, Department of Psychiatry, College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, NY, NY