Parkinson's disease (PD) is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by the prominent loss of dopamine neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta. Although first recognized as a purely motor disorder featuring resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and postural instability, PD is increasingly being conceptualized as a neuropsychiatric disorder because of the high prevalence of nonmotor symptoms.

1 Psychiatric features include depression, apathy, anxiety, psychosis, and sleep disturbance.

Recent studies have identified a subpopulation of PD patients who exhibit impulsive and compulsive behaviors, such as pathological gambling, hypersexuality, compulsive shopping, punding, and binge-eating.

2 Many consider impulse-control disorders (ICDs) to result purely from iatrogenic factors, and symptoms often subside when dopaminergic medications are reduced or replaced. However, several patient factors have been variably linked to ICD manifestation, including male sex, younger age at PD onset, personal or family history of substance abuse or other psychiatric disorders, and a personality style characterized by impulsiveness.

3,4 True prevalence rates for ICDs in Parkinson's disease are not well established;

4 however, preliminary evidence supports the idea that that ICDs are more common in Parkinson's disease than in the general population or in healthy-control subjects. Prevalence estimates range from 0.4% to 10%, depending on the specific ICD.

5 Although several authors have described the phenomenon of binge-eating among PD patients, no reliable point-prevalence estimates have been reported.

4 With regard to the general population, a recently completed, multi-national study identified binge-eating disorder in 1.12% of over 20,000 European participants.

6DSM-IV defines binge-eating disorder as eating an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would eat during the same period of time under similar circumstances, coupled with a perceived lack of control over one's eating (criterion A). Patients with binge-eating disorder must exhibit marked distress regarding binge-eating (criterion C), and three out of five associated features (criterion B). Binge-eating episodes must occur at least twice weekly for a 6-month period (criterion D), and individuals must not engage in inappropriate compensatory behaviors, such as purging or fasting (criterion E). Many researchers have recently supported the consideration of subthreshold eating disorders in the case of individuals who fail to meet all of the above DSM-IV criteria.

6,7 The purpose of the present prospective study was to determine the prevalence of and factors associated with binge-eating disorder and subthreshold binge-eating in Parkinson's disease.

RESULTS

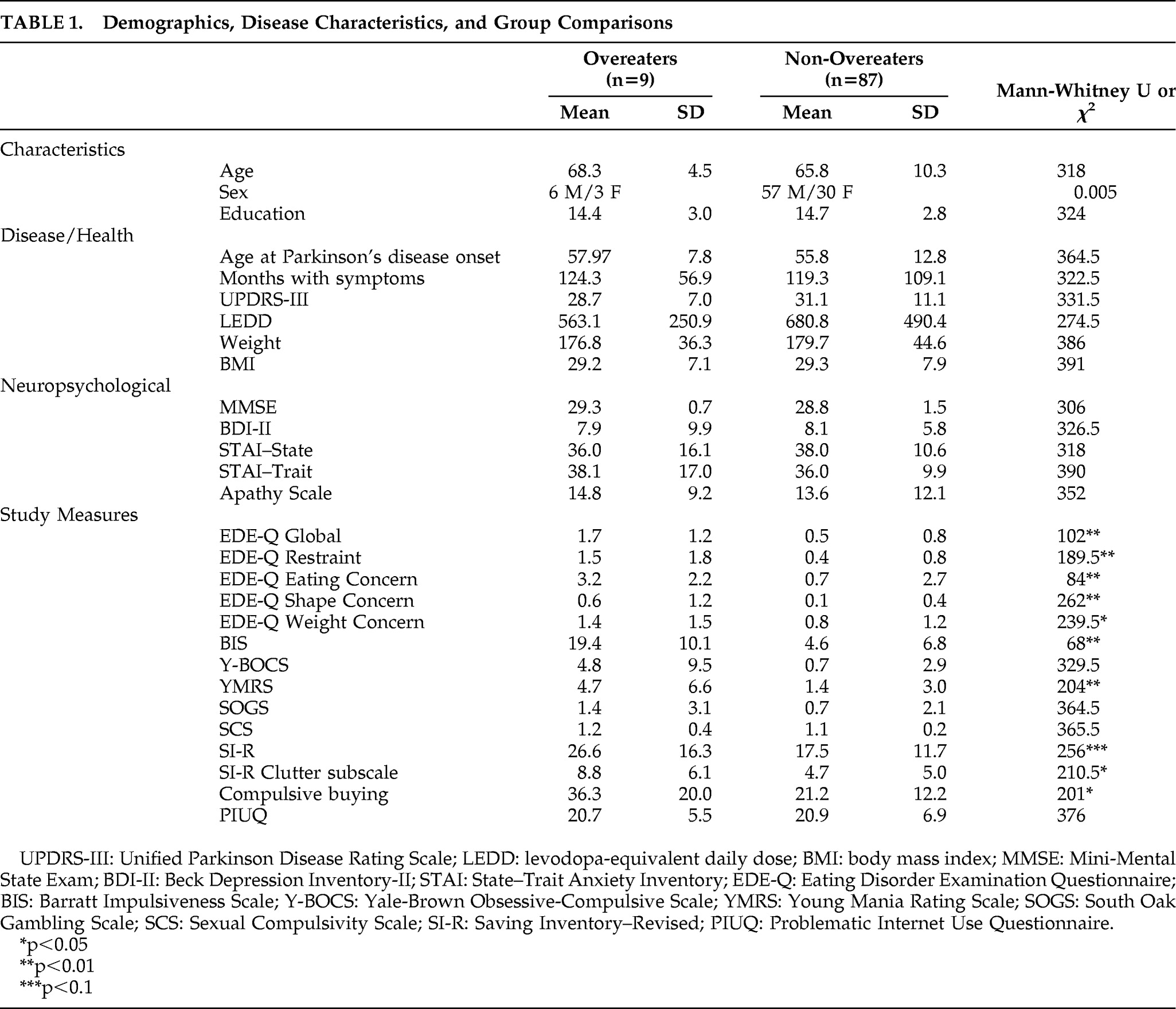

Of 100 consecutive patients approached, 96 patients completed the study. The four patients who declined to participate all cited the number of questionnaires as their reason for refusal. Demographic and disease characteristics of the sample are shown in

Table 1. Of these 96 patients, 22 (22.9%) had previously undergone deep brain stimulation (DBS) surgery in either the internal globus pallidus (6%) or the subthalamic nucleus (17%), whereas 74 (77.1%) were exclusively medically managed. Approximately 42% of patients were taking a dopamine agonist when assessed. On average, patients did not have dementia or depression. Only one patient scored below the cutoff for dementia (MMSE score <24). Seventeen patients evidenced mild-to-moderate depression (BDI score >14).

According to responses on the Eating Disorder Diagnostic Scale, one patient met full diagnostic criteria for binge-eating disorder (1%). An additional 8 patients (8.3%) exhibited subthreshold binge-eating in that they all met criteria A and E for binge-eating disorder. Five patients did not meet criterion B; 2 patients did not meet criterion C; and 1 patient did not meet criteria B, C, or D. This latter individual reported weekly episodes over the last 6 months.

The severity of disordered eating habits was quantified using Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire global scores. In the entire sample, disordered eating correlated with general impulsiveness (r=0.585; p<0.001) and mania (r=0.366; p<0.001). No significant correlations were noted between disordered eating and any of the demographic, disease, or psychological variables.

Table 1 shows that overeaters (N=9) did not differ from non-overeaters (N=87) on any demographic, motor, or mood variables. However, overeaters endorsed greater amounts of overall disordered eating, impulsivity, mania, and clutter behaviors than non-overeaters.

Using psychometric criteria described by the individual scales' developers, the prevalence of impulse control behaviors other than binge eating was determined. Note that DSM-IV clinical criteria were not used to categorize individuals, as a complete diagnostic interview for these other impulse controls disorders was not part of the present protocol. Six patients (6.25%) were identified as probable pathological gamblers; an additional 11 patients (11.5%) had problematic gambling. Eight patients (8.3%) had compulsive hoarding; 11 patients (11.5%) had compulsive buying; one patient (1.0%) had hypersexuality; and one patient (1.0%) had clinically significant manic symptoms. No pathologic Internet use, anorexia nervosa, or bulimia nervosa was found.

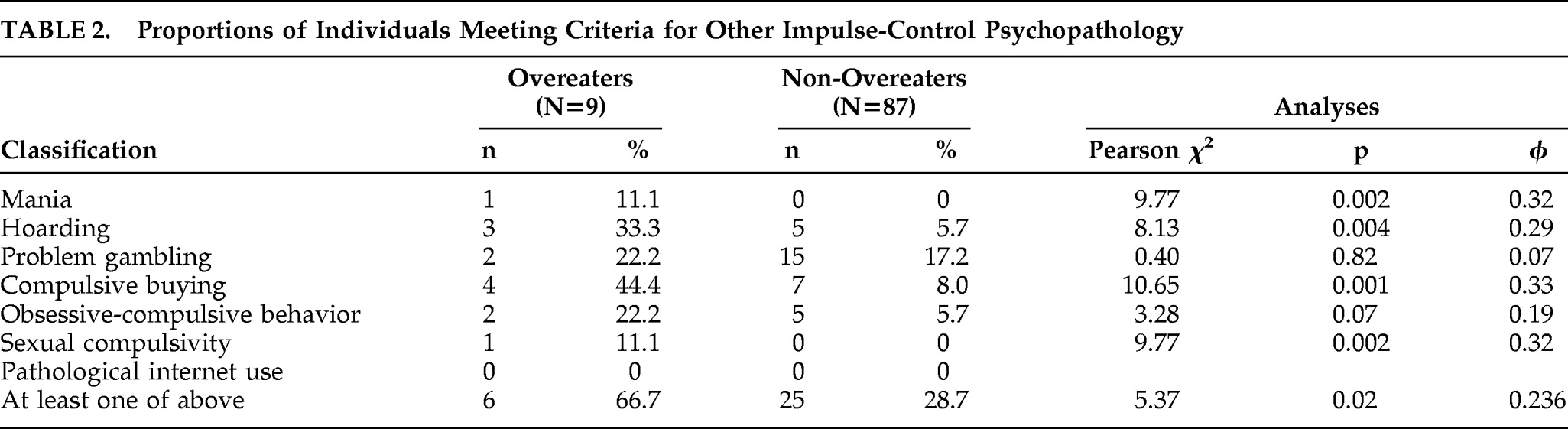

Next, we examined whether overeaters were more likely than non-overeaters to demonstrate other impulse-control behaviors.

Table 2 displays the number of overeaters and non-overeaters who met psychometric criteria in one or more of these domains. As shown, overeaters were more likely than non-overeaters to report mania, hoarding, hypersexuality, and compulsive buying. There was a trend for overeaters to be more likely than non-overeaters to exhibit significant obsessive-compulsive features. Six of the nine overeaters (67%) met psychometric criteria for

at least one other ICD, versus 25 out of 87 non-overeaters (29%). This difference was significant (χ

2=5.367; df=1; φ=0.236; p=0.02).

Four of the nine overeaters (44%) were currently on an agonist, versus 41% of control subjects, and this difference was not statistically significant. Four out of nine overeaters (44%) had undergone subthalamic nucleus DBS surgery, and 0 had undergone internal globus pallidus DBS. Twelve (14%) and six (7%) non-overeaters had undergone DBS in the subthalamic nucleus and internal globus pallidus, respectively. The association between overeating and DBS history (subthalamic nucleus, internal globus pallidus or no DBS) was at trend level (χ2=5.82; df=2; Cramer's V=0.246; p=0.055).

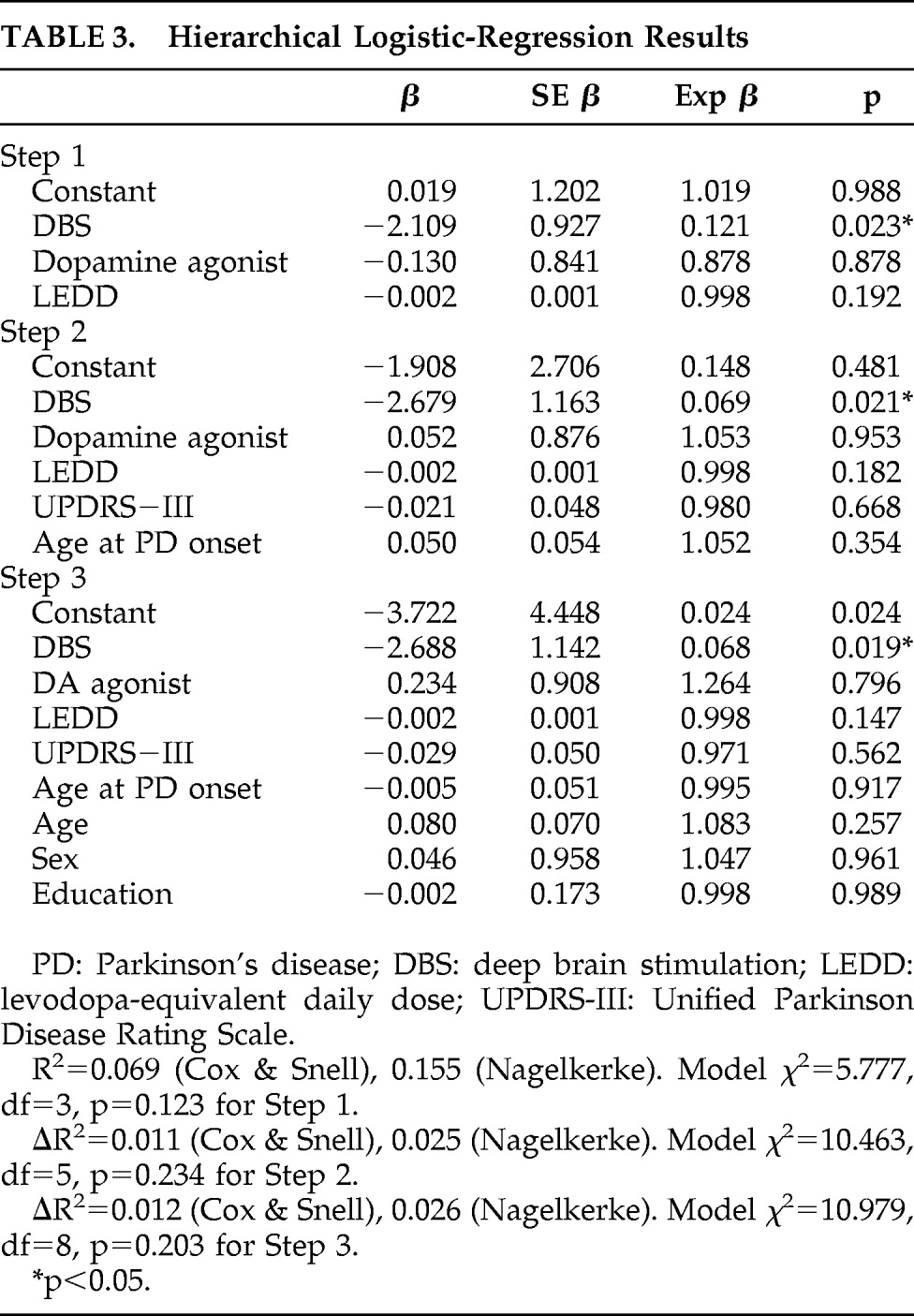

In order to determine the relative contributions of demographic, disease, and iatrogenic variables to overeating, a hierarchical logistic regression was conducted, in which the dependent variable was eating status (Overeater versus Non-overeater). Based on previous research, the first block comprised iatrogenic variables (DBS, dopamine-agonist therapy,

l-dopa equivalent daily dose [LEDD]). The second block comprised disease characteristics (age at PD onset, UPDRS-III total score), and the third block comprised demographic characteristics (age, sex, education). Results are shown in

Table 3. Although the model did not reach significance at any of the three steps, DBS emerged as the only independent predictor of being Overeater status at all three steps (p=0.023 after Step 1; p=0.021 after Step 2; and p=0.019 after Step 3).

DISCUSSION

Our study is cross-sectional, with all of its inherent weaknesses. Nonetheless, the present report describes results from the first prospective study on the point prevalence of binge-eating disorder in Parkinson's disease patients in the United States. It provides further support for a relationship between binge-eating and other behaviors on the impulsive-compulsive spectrum. Results also suggest that future research should explicitly examine the contribution of deep brain stimulation in the subthalamic nucleus to binge-eating behaviors.

We identified the presence of binge-eating disorder in only 1% of our unselected sample of 96 consecutive PD patients, which is comparable to the 1.12% prevalence estimate reported in a recent multinational study.

6 In the future, a larger sample size should be used to confirm this prevalence value. The current estimate of binge-eating disorder prevalence is lower than those reported for pathological gambling and hypersexuality and higher than that reported for compulsive buying in PD.

2 Despite the lack of higher prevalence of binge-eating disorder in this sample of PD patients, we identified subclinical binge-eating disorder in 8% of the sample, which is similar to or higher than rates of other ICDs.

2 Using psychometric criteria, we also identified relatively high levels of problem gambling (11.5%), compulsive buying (11.5%), and hoarding (8.3%) within our sample.

We found substantial support for the co-occurrence of ICD behaviors among individuals with Parkinson's disease. Binge-eating severity correlated with measures of impulsivity and mania. More overeaters met psychometric criteria for at least one other ICD than did non-overeaters. This overlap is consistent with the current view of a common pathophysiological mechanism underlying these behaviors in PD that involve mesocorticolimbic sensitization. Recent neurobiological experiments show enhanced dopaminergic activity within the ventral striatum of PD patients displaying pathological gambling or dopamine dysregulation syndrome (DDS).

23Previous studies have variably identified male sex, younger age at PD onset, and depression as risk factors for ICDs.

2 In our sample, overeaters and non-overeaters did not differ on any of these variables. However, most previous studies focused on pathological gambling. Many have failed to identify these variables as independent risk factors when using multivariate analyses.

4,5 No study has yet examined the contributions of these variables exclusively to binge-eating in Parkinson's disease. Of note, a recent mail-survey study involving 312 PD patients similarly failed to identify male sex, mean daily

l-dopa dose, or age at Parkinson's disease onset as statistically significant predictors of ICD behaviors.

24 These results suggest that additional risk factors for these symptoms must be explored.

Surprisingly, we did not find any association between the use of dopamine agonists and the presence of binge-eating. Multiple studies have implicated dopamine agonists acting on D3 receptors in the pathophysiology of ICDs and repetitive behavior in Parkinson's disease.

4,5,24,25 However, confounding variables such as differing prescribing practices may have contributed to initial findings.

26 A recent meta-analysis failed to demonstrate a significant relationship between ICDs and individual dopamine agonists.

27 A significant percentage of our cohort underwent deep brain stimulation surgery, which could have altered the patients' medication regimen postsurgery.

This study identified a history of subthalamic nucleus DBS surgery as the only significant predictor of binge-eating in a nonselected sample of consecutive PD patients. Furthermore, there was a trend for an association between subthalamic nucleus DBS and being an overeater. However, because the present study did not systematically measure and compare ICD symptomatology before and after surgery, it cannot be concluded that DBS induced binge-eating in these patients. Identification of such a relationship requires future prospective studies with matched controls. None of the four overeaters with a history of subthalamic nucleus DBS carried a psychiatric diagnosis before surgery. However, it is not known whether they demonstrated subclinical symptoms. Of note, two of these four overeaters described an increase in their desire for sweets (i.e., candies and ice cream) after DBS.

Reports of the effects of DBS on impulsive and compulsive behaviors have been somewhat conflicting and have included descriptions of worsened, improved, and newly-developed ICDs after surgery.

28–31 All four overeaters with a history of DBS in the present study were implanted in the subthalamic nucleus, and it has been suggested that subthalamic nucleus DBS results in more nonmotor complications than DBS in other targets.

32,33 Further controlled studies are needed to determine the specificity of our findings to DBS in the subthalamic nucleus. Interestingly, recent experimental evidence has shown that high-frequency stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus modulates neurotransmission in limbic regions such as the nucleus accumbens shell, which has been implicated in the pathophysiology of ICDs.

34Weight-gain after DBS has been documented by numerous groups.

35 Bilateral and unilateral subthalamic nucleus stimulation have been associated with weight-gains of approximately 10 kg and 4 kg after 1 year, respectively.

35 Postsurgical weight-gain has been attributed to medication reduction, improved ability to eat, and/or decreased basal energy expenditure.

36 Despite reports of uncontrolled appetitive behaviors after DBS, the potential effect of increased frequency of binge-eating episodes has not yet been systematically evaluated.

The relatively high prevalence of clinical and subclinical symptomatology reported here suggests that physicians should be aware of binge-eating in their PD patients, especially considering the potential adverse consequences of prolonged occurrences. The relationship between binge-eating and weight-gain after DBS surgery should also be elucidated, as it is important for physicians and patients to be cognizant of potential surgical side effects during treatment planning.