Processing-deficits in the interpersonal sphere can constitute presenting symptoms and a prominent dimension of the natural history of brain diseases. Social impairments and their underlying bases have been a longstanding theme in neurobehavioral study of patients with frontal lobe syndromes.

1–4 These observations have become increasingly important with identification of frontotemporal dementia (FTD).

5 Progressive social impairments are a major clinical feature of FTD, principally in the subgroup manifesting significant behavioral, personality, and executive-functioning deficits (i.e., behavioral-variant FTD [bvFTD]).

6–8 In contrast to other prominent neurodegenerative diseases, bvFTD patients do not present with prominent speech, language, or general-knowledge disorders, as in progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA) and semantic dementia (SD), nor do they manifest progressive short-term memory deficits, such as in Alzheimer's disease, or progressive motor, apraxia, and sensory symptoms, as in corticobasal syndrome. Hence, their subtle, but progressively disabling, social deficits can go unrecognized or misdiagnosed for years.

Recent investigations of bvFTD have begun to evaluate their underlying deficits by using various correlates of social impairments.

9–14 In a neural-systems model of social cognition, we have proposed important interrelationships of social and cognitive domains in a

social executor framework of deficits in bvFTD,

15 drawing from social-cognitive studies in adult patients with acquired focal lesions of the frontal lobe.

16–18 Social executors encompass social knowledge

and executive resources (including self-awareness and self-regulation), as well as motivational and emotional components associated with interpersonal actions. Social knowledge elaborates the store of social perceptions, actions, experiences, and sequences that are bound by learned rules, conventions, and conditional probabilities, typically what is identified as social cognition. In this view, effective utilization of social knowledge is also constrained by several allied processing resources that are specific to the social domain (e.g., theory of mind, empathic sensitivity), by domain-neutral executive resources (e.g., cognitive flexibility, self-awareness, self-regulation), and by motivational and emotional influences that bias social perceptions and actions (e.g., social emotions).

19–21Empathy is an important domain of social emotion and cognition that influences interpersonal judgment, emotions, and behavior.

22,23 Cognitive (i.e., perspective-taking) and emotional (i.e., sensitivity, attachment) resources may be activated in empathy and serve to foster shared interpersonal experiences and understanding of other's experiences and mental states. Changes in empathy have been noted in clinical descriptions of FTD,

5 as well as in studies of focal frontal-lobe lesions.

17,24 A standardized survey of caregivers

25 identified cognitive-empathic changes in a frontal-variant FTD sample and decline in both cognitive and emotional empathy in a temporal-variant FTD sample. A second, larger sampling of caregivers reported both cognitive and emotional empathic changes in FTD patients with frontal-related behavioral changes and with features of semantic dementia (SD), although changes were not detected in patients with progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA).

26 When caregivers rated empathic behaviors pre- versus post-disease onset in a sample of frontal-variant FTD patients, significant decline was detected in both cognitive and emotional empathy.

9 Hence, we hypothesized that analysis of a standardized behavioral inventory would confirm significant cognitive and emotional empathic deficits in a bvFTD sample, although we were uncertain about empathic changes in an FTD aphasic sample (SD and PNFA), since we have not observed such changes in previous research or in clinical care. Although limited insight into their own social deficits has been documented in previous studies of bvFTD,

11,12 few studies have specifically compared ratings of empathy in bvFTD patients with the ratings of their caregivers.

Social disorders in bvFTD have been associated with predominantly right-sided pathophysiology.

27,28 Rankin et al.

26 directly related empathy and cortical atrophy in a large group of patients with various neurodegenerative conditions. They reported an association of overall empathy score with atrophy in the right temporal pole, right fusiform gyrus, and the right medial frontal region. In this mixed sample, emotional empathy was related to the right temporal pole, right subcallosal gyrus/caudate, and right inferior frontal gyrus, whereas cognitive empathy also was related to the right temporal pole, right subcallosal gyrus/caudate, and right fusiform gyrus. When subgroups of their sample were examined, total empathy score was related to the right subcallosal gyrus in bvFTD and to the right temporal pole in SD.

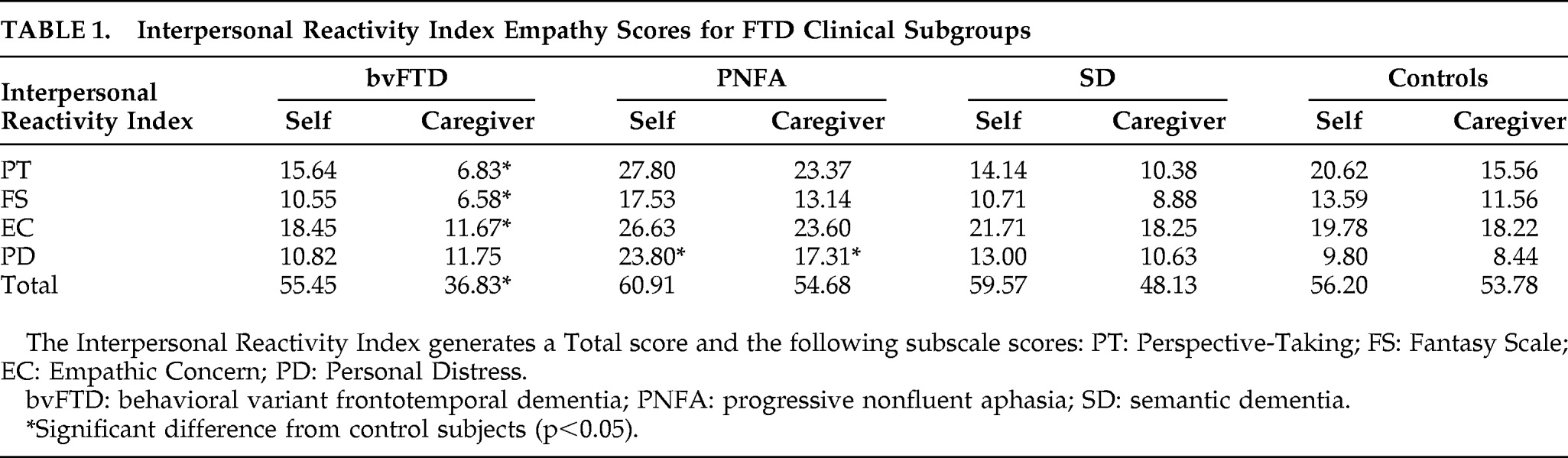

The present study was designed to characterize interpersonal deficits in bvFTD more clearly, by investigating multiple dimensions of empathy from the social executor perspective. Specifically, we investigated empathy-related behavioral changes in FTD samples (bvFTD, PNFA, SD) and healthy-control participants, utilizing patient ratings and caregiver ratings, on a standardized survey scale, the Interpersonal Reactivity Index (IRI).

22 We were particularly interested in determining the contribution of social and executive factors to empathic changes, including cognitive (i.e., social perspective-taking) and emotional (i.e., social-emotional concern) aspects of empathic behaviors. We also investigated the neural correlates of empathic deficits in bvFTD by use of voxel-based morphometry. We expected that cognitive and emotional deficits in empathy in bvFTD would be related to distinct impairments of executive resources and emotional knowledge. Moreover, we expected changes in cognitive and emotional forms of empathy to be associated with distinct neural substrates.

DISCUSSION

Results support a model of multiple associations among social-cognition, empathy, and executive functioning resources that break down in multivariate, convergent fashion in FTD patients with prominent social and executive impairments. Standardized caregiver ratings of empathy-related behavioral changes in FTD identified marked decrements in both cognitive (i.e., perspective-taking) and emotional (i.e., emotional concern) aspects in bvFTD patients. These results parallel the findings of previous work.

9,26 The lack of empathy in bvFTD is extraordinarily disturbing to caregivers.

14 Such changes were not evident in the caregiver ratings for the PNFA and SD samples, supporting the specificity of the results for the consensus diagnosis of bvFTD disorders and presumed frontal-limbic involvement. The lack of observed empathic changes in SD patients, as seen by Rankin et al.,

26 may be related in part to an ascertainment bias. That is, patients referred to our center may have comparatively less prominent social features than patients referred to the center where Rankin et al. completed their study. Additional multicenter studies are needed to resolve issues such as the nature and severity of social disorders in patients with progressive aphasia.

Observations of empathy changes similar to our study findings underscore the profound and wide-ranging empathic deficits in bvFTD, involving both cognitive and emotional forms of empathy. Also, we sought to investigate the basis for the empathic deficit in bvFTD by analyzing close associations. According to the social executor model, social knowledge as well as social and domain-neutral executive resources contribute to complex processes like empathy. From this perspective, we were particularly interested in determining whether social and executive resources are related to empathic limitations in bvFTD. We found that decline in the cognitive or perspective-taking aspects of empathy correlated significantly with social-cognitive (i.e., Theory of Mind and Cartoon Predictions) and executive (i.e., Cognitive Flexibility) measures. Decline in emotional empathy correlated only with executive functioning. These observations suggest an ideational association between social-cognitive resources and empathy, and, moreover, suggest that resources may be shared across social-interpersonal and executive cognitive processing. Such correlations have been suspected in bvFTD patients on the basis of results of clinical studies, and overlapping pathophysiology that has been identified in focal frontal lesion cases

17 and in previous assessments of social cognition in bvFTD.

12,15 For example, during a three-alternative, forced-choice, social problem-solving task, we identified a significant deficit in bvFTD. Correlational analyses revealed that performance was related to theory of mind, empathy, and cognitive flexibility measures.

12 A regression analysis demonstrated that the measure of cognitive flexibility accounted for the largest portion of the variance in social judgment performance. Observations such as these and the findings of the present study provide support for the social executor model.

Previous work has examined the relationship between disorders of social functioning and executive-resource limitations in bvFTD. The results have been inconsistent across studies, and likely related to differences in the tasks used to probe empathy and cognition in the patients and caregivers being probed. Similar to Rankin and colleagues, we used the IRI to determine whether distinct forms of empathy may be identified in bvFTD. We found confirmatory evidence that the correlation between cognitive and emotional forms of empathy can make it difficult to dissociate these two easily in bvFTD patients. On the other hand, the subgroup of patients with bvFTD have significant executive-function deficits,

42,43 and it is reasonable to propose that the social disorder in bvFTD is due in part to their executive-resource limitations. Although we demonstrated this in our previous assessments of social problem-solving and self-awareness,

12,15 such associations between social-emotional and executive-cognitive functioning may not have been seen in other work because of limited ascertainment of cognitive measures, such as assessment of a partial range of relevant measures. For example, Lough and coworkers

9,41 examined a limited range of executive measures requiring cognitive estimation, but did not assess measures of mental flexibility that may be a more pertinent cognitive component of empathy. Alternately, there may be qualitative or quantitative differences between the patients assessed in different studies. There may be differences in the severity of disease across bvFTD patients participating in different studies. This is difficult to ascertain since there is no universally accepted measure of severity for patients with FTD. On the basis of disease duration, our patients were mildly-to-moderately impaired. A second, patient-related issue is concerned with the qualitative nature of bvFTD. Previous criteria were not necessarily reliable at identifying these patients,

45 and there is an ongoing effort to improve diagnostic criteria for bvFTD.

13,46 Moreover, the bvFTD phenotype does not differentiate between the subgroup of FTD patients with predominantly frontal disease and predominantly temporal disease. Recent work has associated social knowledge more prominently with right anterior temporal regions,

20,47 although resource-dependent social functioning may be mediated more by the right frontal lobe. It may be that patients participating in studies are not equated in the burden of frontal and temporal disease. From this perspective, the presence of frontal disease critically interferes with implementing social knowledge in a flexible and adaptive manner in social situations, and the patients we examined in the present study have sufficient frontal disease to interfere with this component of empathy.

Lough et al.

9 emphasized the importance of the informant report for detection of empathy-related changes in FTD, since the comparison of patient and caregiver behavioral ratings provides important observations about the degree of self-awareness changes in FTD. The degree of discrepancy we evaluated was based on comparison with healthy-controls and their informants, ensuring a conservative analysis that considered naturally-occurring differences between participants and their informants. Furthermore, PNFA and SD samples showed virtually no significant discrepancies from their informants. The single exception was higher Personal Distress ratings in PNFA patients, also identified by their informants, and this may have been related to their highly frustrating speech impairments. It is noteworthy that bvFTD patients and their caregivers appeared to agree on their normal range of Personal Distress ratings. This may reflect the fact that the patients had little insight into their difficulties and thus were not evidently distressed, resembling control subjects who were not distressed, in the context of having no neurodegenerative disease. The predominant pattern of the bvFTD patients was not to identify any empathy-related behavioral changes, in marked contrast to caregiver observations. This loss of social self-awareness, which is a key domain of social executors,

18 is consistent with systematic observations from other measures,

11,12 as well as clinical correlation to right-frontal hypoperfusion.

48 Thus, bvFTD patients exhibit not only significant social-cognitive, executive, and empathic alterations, but also a lack of awareness of their social insensitivity

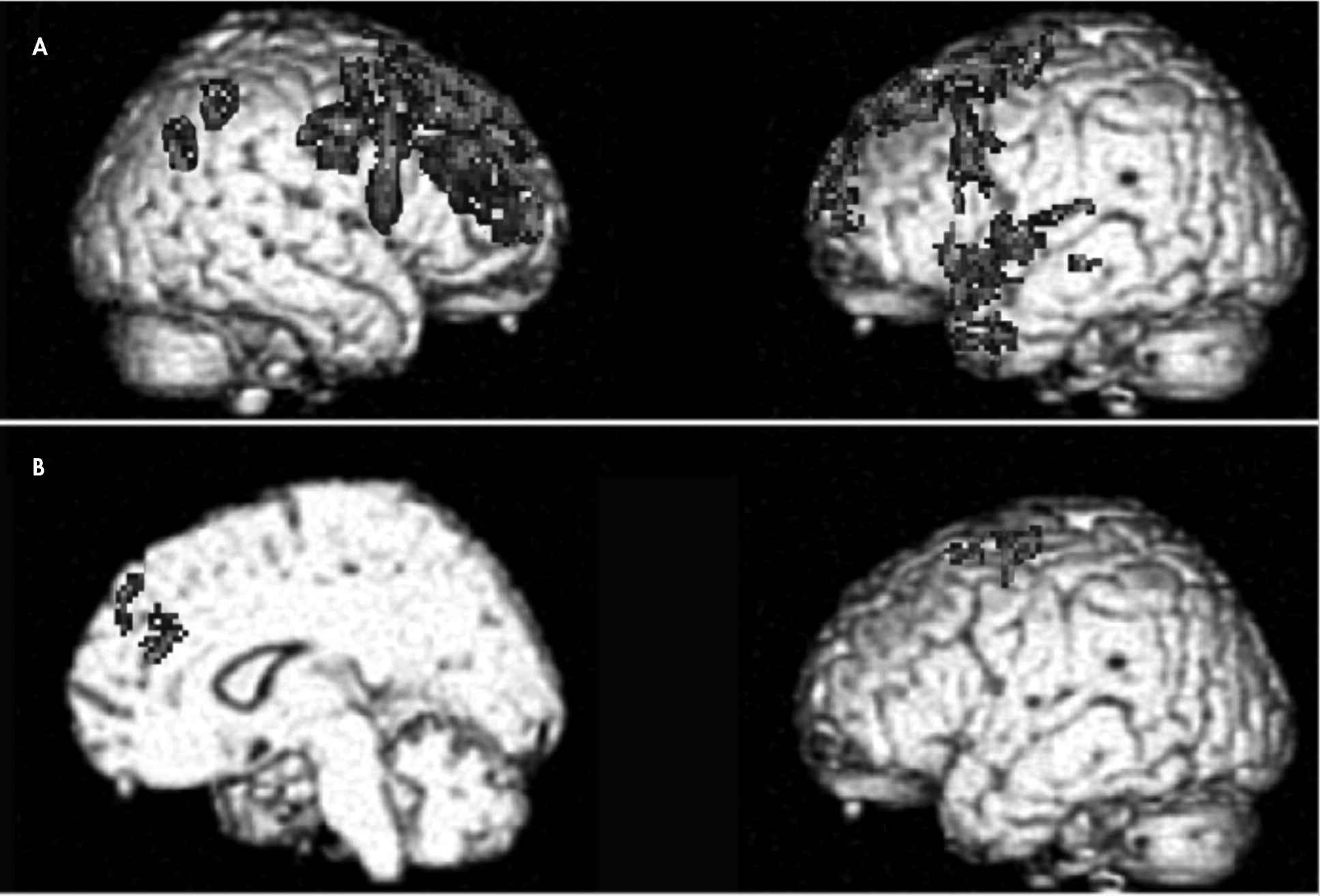

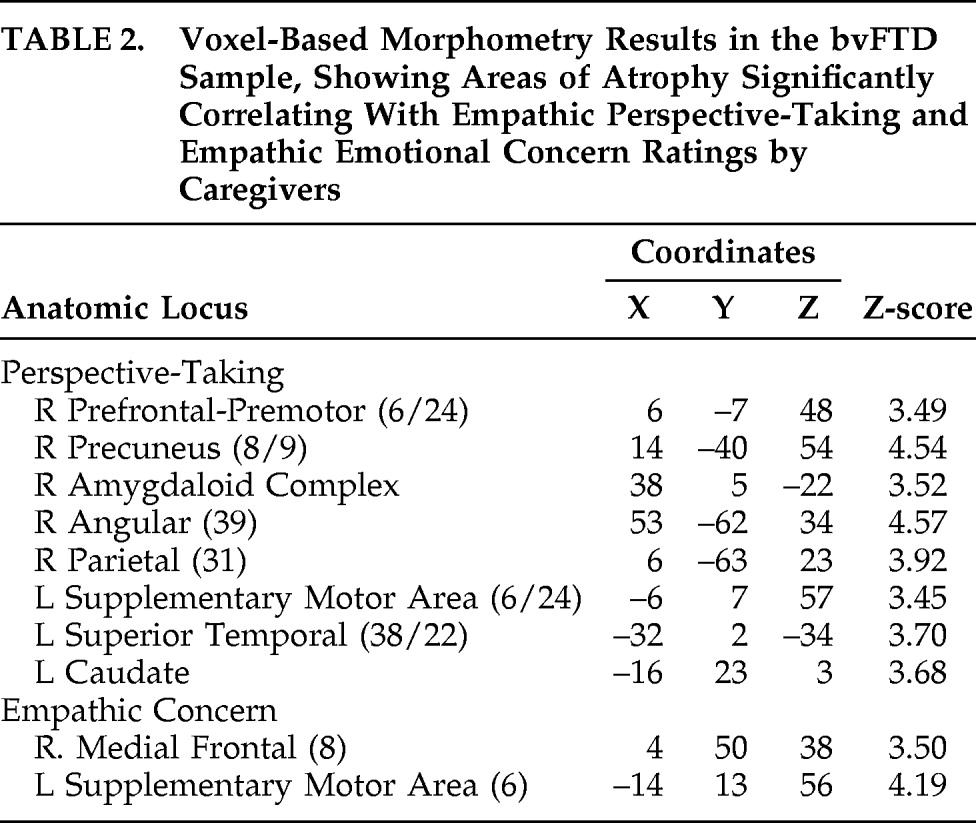

As might be expected on the bases of lesion and functional-imaging studies,

23,49 cognitive and emotional empathic changes were associated with pathophysiology in different cortical and subcortical regions. Empathic perspective-taking was correlated with widespread areas of the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, extending from premotor to polar regions, left superior mesial prefrontal-premotor cortices, right parietal regions, and left superior temporal gyrus and temporal pole, as well as subcortical areas of the right amygdala and left caudate. These cortical areas have been associated with theory-of-mind processing, executive functions of planning, cognitive flexibility and foresight, social knowledge, multiple cognitive aspects of empathy (e.g., valuation of thoughts, social emotions, one's own behavior and the behavior of others, recognition of alternative actions), and cognitive–emotional integration.

50–55 In contrast, empathic emotion was correlated with more restricted right superior mesial cortex changes, an area implicated in shared self–other representations, as well as self-referencing of emotion and volition.

49,56 These results are also consistent with the suggestion by Mendez

57 that the decline in moral judgment in FTD patients with frontal-variant symptoms may arise in part from an empathic loss in emotionally identifying with others. In the only other study to date examining anatomical correlates of empathy changes in bvFTD, a combined empathy score was related to structural integrity of the right subcallosal gyrus, with scores from a larger, mixed neurodegenerative disease group associating empathy with atrophy in right frontal-temporal regions, particularly the temporal pole, subcallosal gyrus, and caudate and fusiform gyrus.

26 Our results suggested distinct differences between anatomical correlates for empathic perspective-taking and empathic emotional concern, although both showed strong frontal-lobe correlations. These cognitive and emotional empathic changes in our bvFTD sample are consistent with extensive literature based on clinical lesion analysis, functional brain imaging, and connectional anatomy in nonhuman primates, indicating that the prefrontal regions are involved in cognitive and emotional processing, and, quite likely, complex integration of cognition and emotion.

20,23,53,58–62The findings confirm and extend the observations regarding multiple behavioral, cognitive, and social-emotional symptoms and deficits in bvFTD patients. The results support the conclusion that several of these are interacting and synergistic effects of pathophysiology in the frontal, anterior temporal, and interconnected subcortical regions in this clinical group, giving rise to these clinical deficits. The measures used appear to provide both sensitive and quantitative assays of fronto-temporal functions affected in bvFTD patients, and these may constitute informative screening instruments.