Physicians working in inpatient neurorehabilitation settings are often asked to evaluate the cognitive status of persons with recent traumatic brain injury (TBI) and to give opinions on likely rehabilitation outcomes. Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS)

1 scores and/or estimates of posttraumatic amnesia duration, when available, may be useful toward these ends.

2,3 Unfortunately, these assessments are not consistently present in medical records.

4 Formal neuropsychological assessment also may be used for these purposes.

5 However, access to neuropsychological assessment services in the inpatient neurorehabilitation setting varies widely.

6 Also, the timing, content, and advisability of performing of such assessments during acute inpatient TBI neurorehabilitation are matters of debate.

5 Physicians therefore often rely on assessments such as the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE)

7 or clock-drawing tests

8 when performing bedside cognitive evaluations and developing preliminary TBI neurorehabilitation outcome predictions.

Clock-drawing is a relatively time-efficient cognitive screening assessment that is useful in the evaluation of patients with a broad range of cognitive abilities and is easily performed by physicians.

9 For these reasons, clock-drawing is generally included in the Behavioral Neurology & Neuropsychiatry (BNNP) consultations we perform on our inpatient TBI neurorehabilitation service. To our knowledge, however, clock-drawing has not been described as a cognitive assessment or outcome predictor among persons receiving inpatient neurorehabilitation after TBI.

RESULTS

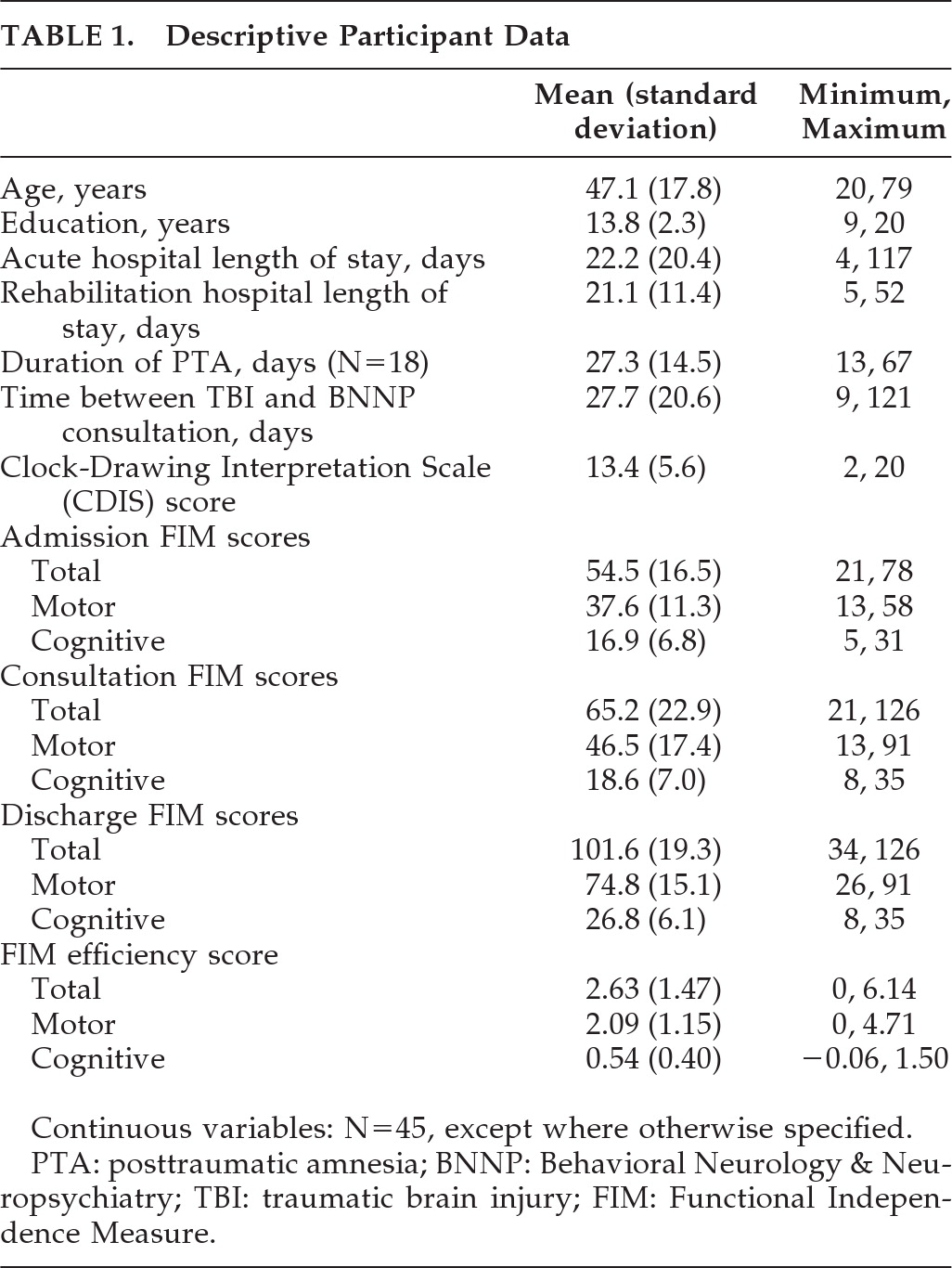

A total of 45 participants (10 women) met study inclusion criteria; these patients are described in

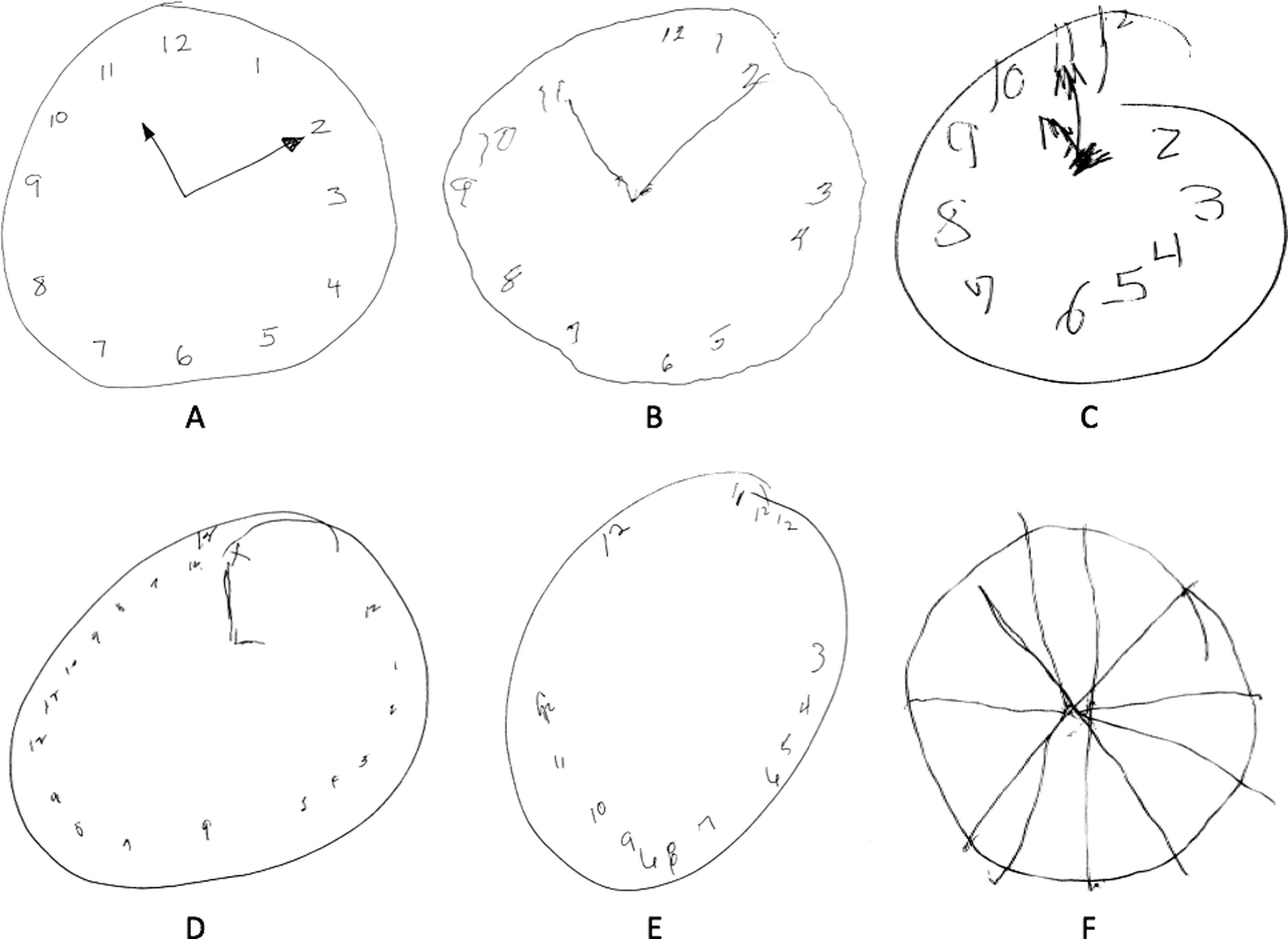

Table 1 and examples of the clock drawings produced by this patient group are presented in

Figure 1. Among these patients, causes of TBI included motor vehicle accidents (44.4%), falls (35.6%), sports/recreation (13.3%), and assaults (6.7%). At the time of rehabilitation admission, 18 patients (45.0%) were in posttraumatic amnesia; 11 (24.4%) were still in posttraumatic amnesia at the time of BNNP consultation (usually 5–6 days after rehabilitation admission). Mean CDIS score was 13.4 (standard deviation [SD]: 5.6), with a range of 2 to 20 (with a possible range of 0 to 20); these scores were normally distributed (Kolmogorov-Smirnov

d=0.19, NS).

Regression Modeling of FIM Scores and RLOS

CDIS score inversely correlated with patients' age (r = –0.41; p<0.005) but not education (r = –0.06; NS). After controlling for age, CDIS score predicted total FIM at consultation (adjusted R2=0.31; β=0.62; p<0.001) and discharge (adjusted R2=0.19; β=0.41; p<0.005) as well as Cognitive and Motor FIM subscale scores at consultation (adjusted R2=0.27; β=0.56; p<0.001 and adjusted R2=0.27; β=0.60; p<0.001, respectively) and discharge (adjusted R2=0.28; β=0.36; p<0.001 and adjusted R2=0.12; β=0.37; p<0.03, respectively). The combination of CDIS score and age predicts total FIM efficiency (adjusted R2=0.10; p<0.05). In this model, CDIS score contributed more strongly (β=0.30; p=0.06) than did Age (β = –0.13; NS). This combination predicts Motor, but not Cognitive, FIM efficiency (adjusted R2=0.11; p<0.04); CDIS score, but not age, contributed significantly to this model (β=0.34; p<0.04). Also, CDIS score predicts rehabilitation length of stay (adjusted R2=0.22; β = –0.53; p<0.002).

DISCUSSION

The CDIS performs well as a cognitive assessment in this population, yielding a broad and normally distributed set of values. CDIS predicts functional independence at the time of BNNP consultation as well as rehabilitation discharge, accounting for 31% and 19% of the variance in total FIM scores at these time-points, respectively. CDIS score accounted for 27% of the variance in both Motor and Cognitive FIM scores at the time of BNNP consultation as well as 12% of Motor FIM scores and 28% of Cognitive FIM scores at rehabilitation discharge. CDIS also predicts duration of inpatient rehabilitation hospitalization, accounting for 22% of the variance in rehabilitation length of stay. To our knowledge, this is the first report describing clock-drawing performance (and the CDIS, specifically) as a cognitive assessment and an outcome predictor among inpatients receiving neurorehabilitation after TBI.

The combination of CDIS and age predicts FIM efficiency—the rate of improvement in functional independence, defined as change in FIM score per day of rehabilitation—accounting for 10% of the variance in FIM efficiency score. In this model, CDIS trends toward independent prediction of FIM efficiency and independently predicts Motor FIM efficiency. It is likely that its failure to serve as an independent predictor of Cognitive FIM efficiency reflects inadequate power to do so as a result of this study's relatively modest sample size and the narrow distribution of Cognitive FIM efficiency scores.

Clock-drawing tests are used most often as qualitative assessments of cognition. However, this study suggests that there may be value to standardized administration and scoring of this test when assessing cognition and predicting functional status among persons with TBI in the inpatient rehabilitation setting. As reviewed and discussed by Shulman,

9 clock-drawing possesses many of the qualities of an ideal cognitive screening test. Among the most relevant of these qualities to the present study are ease of administration and scoring, tolerability and acceptability to patients, relative independence from the effects of culture, language, and education, and, with respect to functional status and rehabilitation lengths of stay, predictive validity. The clock-drawing test used in our neuropsychiatric consultations adheres strictly to a script,

8 in order to minimize examiner-specific influences on patient performance. When selecting a method for quantitative interpretation of clock-drawing performance, we sought one that provided easily-applied objective scoring anchors and, in light of our previous observations in this population,

14,15 emphasized assessment of impairments in frontally-mediated cognition. Among the measures we considered,

9 the CDIS

13 appeared to meet these needs. This characteristic, we believe, also offers the most likely explanation for the predictive relationship between CDIS score and inpatient rehabilitation outcomes observed in this group of subjects with TBI.

Limitations of the present study include its retrospective design and use of data collected originally for clinical rather than research purposes. The measure used to interpret clock-drawings in this clinical sample, the CDIS, was not developed originally as an assessment of posttraumatic cognitive impairment. We also did not perform formal data-driven comparison of the CDIS with other clock-drawing scoring methods before performing the study described here. However, the psychometric properties of the CDIS are well-established,

9 and its preliminary performance as a variable with which to test our study hypotheses was productive.

Although the CDIS was used in this study to predict functional status and rehabilitation outcomes among persons with TBI, we do not believe that this predictive relationship is specific to this population. Based on more than a decade of performing BNNP consultations in inpatient neurorehabilitation settings, we hypothesize that CDIS scores also will predict functional status and acute inpatient neurorehabilitation outcomes among persons with other recent-onset neurological disorders (e.g., stroke, hypoxic-ischemic brain injury, cerebral neoplasms). Testing this hypothesis will require prospective studies on these populations, the results of which will inform usefully on the merits of routinely incorporating the clock-drawing test into BNNP consultations performed in such settings.

The present study also does not inform fully on the cognitive and noncognitive contributors to clock-drawing performance in this population or their contributions to the variance in functional status and rehabilitation outcomes not accounted for by CDIS scores. Identification of the cognitive contributors to clock-drawing performance will require concurrent evaluation with a neuropsychological testing battery that is appropriate for use in an inpatient neurorehabilitation setting.

5,16 Identification of the noncognitive contributors (e.g., disinhibition, perseveration, depression, anxiety, apathy) to clock-drawing performance will require use of a measure such as the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Nursing Home version,

17 which facilitates neuropsychiatric symptom-identification among patients with limited capacity for accurate self-report. Pending the performance of prospective studies that address these issues, our suggestion that the relationship between clock-drawing performance and functional status reflects frontally-mediated cognition remains speculative.

With these limitations in mind, translation of the statistical relationships identified here between the CDIS and our rehabilitation outcome variables is premature. On the other hand, the ability of the CDIS to predict rehabilitation outcomes in a data set derived from everyday clinical practice suggests that these observations may be more readily applied to clinical populations than those derived from a rarified research population. Further study of these issues in a manner that overcomes the limitations of the present study is warranted.