There has been debate about whether posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can occur after severe head injury (SHI), when there is usually little or no recollection of the actual traumatic event.

1 Head injury impairs memory for trauma as a result of loss of consciousness, posttraumatic amnesia (PTA), and retrograde amnesia. Hence, the basis for reexperience is limited, and this limitation might provide protection from psychological trauma. Fear associated with traumatic experiences may be mediated by subcortical structures, allowing development of reexperience phenomena after SHI, as represented by emotional and physiological reactivity, and damage might explain the lower incidence of intrusive phenomena.

2 Indeed, several studies on PTSD after SHI report low frequencies of intrusive symptoms, and some report an absence of “reexperience” symptoms.

2–5 A protective effect of SHI might, for some patients, prevent PTSD from arising and, for others, result in “partial” PTSD, where all symptom criteria are not met.

6 There is interest in “partial” PTSD after non-head-injury–related trauma,

7 but, as yet, this is not reflected in studies on head injury.

Diagnosis of PTSD after head injury is complicated by symptoms that are common to both. Also, the cognitive sequelae of head injury often include impairment of attention and inflexible thinking, and these factors can also lead to errors in diagnosis.

8 Furthermore, people with head injury are often curious about the “amnesic gap” in their lives during the traumatic event. This curiosity can have an intrusive quality, without associations associated with anxiety or fear, but can be confused with reexperience.

4 If PTSD occurs after SHI in “partial” form, this phenomenon might explain the wide range of occurrence of PTSD (0–27%) reported after SHI,

2,3,8 and there are implications for diagnosis and treatment after head injury.

Here, we investigate whether partial PTSD occurs after SHI. If partial PTSD is common after SHI, then emotional responses associated with PTSD (attention bias to trauma-related threat stimuli and heart rate reaction) when asked to remember the trauma would be associated with PTSD symptom severity.

HYPOTHESES

Evidence for partial PTSD after SHI will be supported if higher PTSD symptom severity scores are associated with 1) attention bias toward trauma-related words; and 2) increase in heart rate when discussing the traumatic event.

METHOD

Participants were recruited from a neurorehabilitation unit and from a brain-injury charity organization. Ethics approval was granted by NHS Lothian. Inclusion criteria were the following: over age 17 years, IQ over 79, not color-blind, SHI (PTA>1 day), ≥3 months post-injury (DSM-IV criterion for PTSD), and living independently.

Measures

Participants were administered the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS)

9 and the Traumatic Memory Inventory (a structured interview assessing memory for the event; only current memory was assessed, as described previously;

6 see Van der Kolk BA: Traumatic Memory Inventory [TMI]; Boston, MA, 1990; unpublished report obtained directly from the author). Severity of brain injury was estimated by retrospective assessment of PTA.

10 The Wechsler Test of Adult Reading yielded a pre-injury estimate of IQ.

11The Stroop Test was modified to assess attention bias. It consisted of traumatic, negative, neutral, and positive words that were selected on the basis of a pilot study (details available from corresponding author). Fifteen words of each type were repeated four times (once in red, blue, yellow, and green ink). A practice trial consisted of numbers

1, 2, 3, 4, and

5 presented randomly in red, blue, green, and yellow ink. The test was presented electronically, by laptop, using Superlab V4.0 with a Cedrus RB-730 response box),

12 with automatic recording of errors and response times. Words were presented pseudo-randomly, with the same word or color never appearing consecutively. Heart rate was estimated using the Garmin-Forerunner 50 Heart Rate Monitor.

Statistical Analysis

Tests were two-tailed. Nonparametric statistics were used if data were not normally distributed.

RESULTS

All 42 participants sustained a severe head injury (PTA 1–7 days: 41%; 8–28 days: 26%; >28 days, 33%). Causes of injury were road traffic accident (47%), fall (36%), and assault (17%). On the TMI, 39 (93%) reported some recall of the event (mean score 2.74; standard deviation [SD]: 1.73).

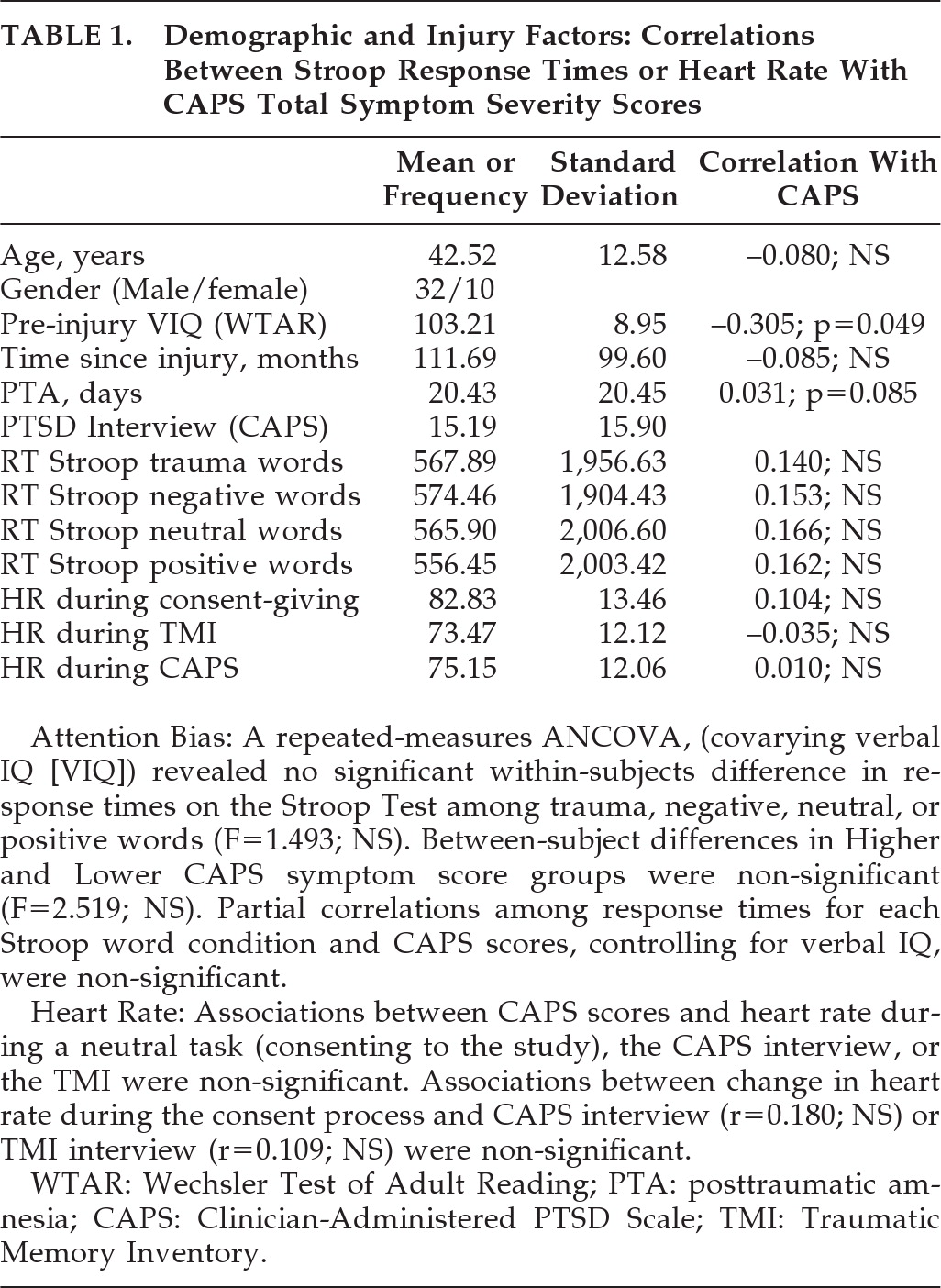

On the CAPS, the proportion with no re-experience symptoms (88%) was much greater than for avoidance (48%) or hypervigilance (45%). Two people (5%) achieved PTSD “caseness” on the CAPS (DSM-IV criteria B–F); both had some memory of the trauma. CAPS symptom severity scores were not associated with age, time since injury, or PTA duration; higher CAPS scores were associated with estimates of lower pre-injury verbal IQ (

Table 1). For ANCOVAs, two PTSD symptom severity groups were divided by median split as “higher” (mean: 27.14; SD: 14.35) or “lower” (mean: 3.24; SD: 14.35).

DISCUSSION

The sample was demographically representative of people with severe head injury.

4,13 Evidence for attention bias or heart rate response might be expected if “partial” PTSD is common after SHI,

5 and, in turn, PTSD symptoms might be expected in this SHI sample because 93% reported some memory of the traumatic event. However, associations between PTSD symptom severity and attention bias or heart rate were not found. Consistent with other reports, few participants reached the DSM-IV criterion for reexperience.

3,4 In fact, the frequency of PTSD “cases” is lower than reported in the general population in victims of road traffic accidents or assaults.

5 These findings support the view that SHI protects against the development of PTSD.

3,6,8,14 Clearly, symptoms of avoidance and arousal can arise independently of PTSD in people who suffer a brain injury. These include anxiety and adjustment issues associated with the trauma and its consequences, memory impairment, difficulty concentrating, sleep difficulties, and irritability.

4 Hence, the low rates of re-experience symptoms after SHI found here are more likely to reflect a low true rate of PTSD, rather than PTSD in a “partial” form.

Acknowledgments

This research was part funded by NHS Education Scotland.