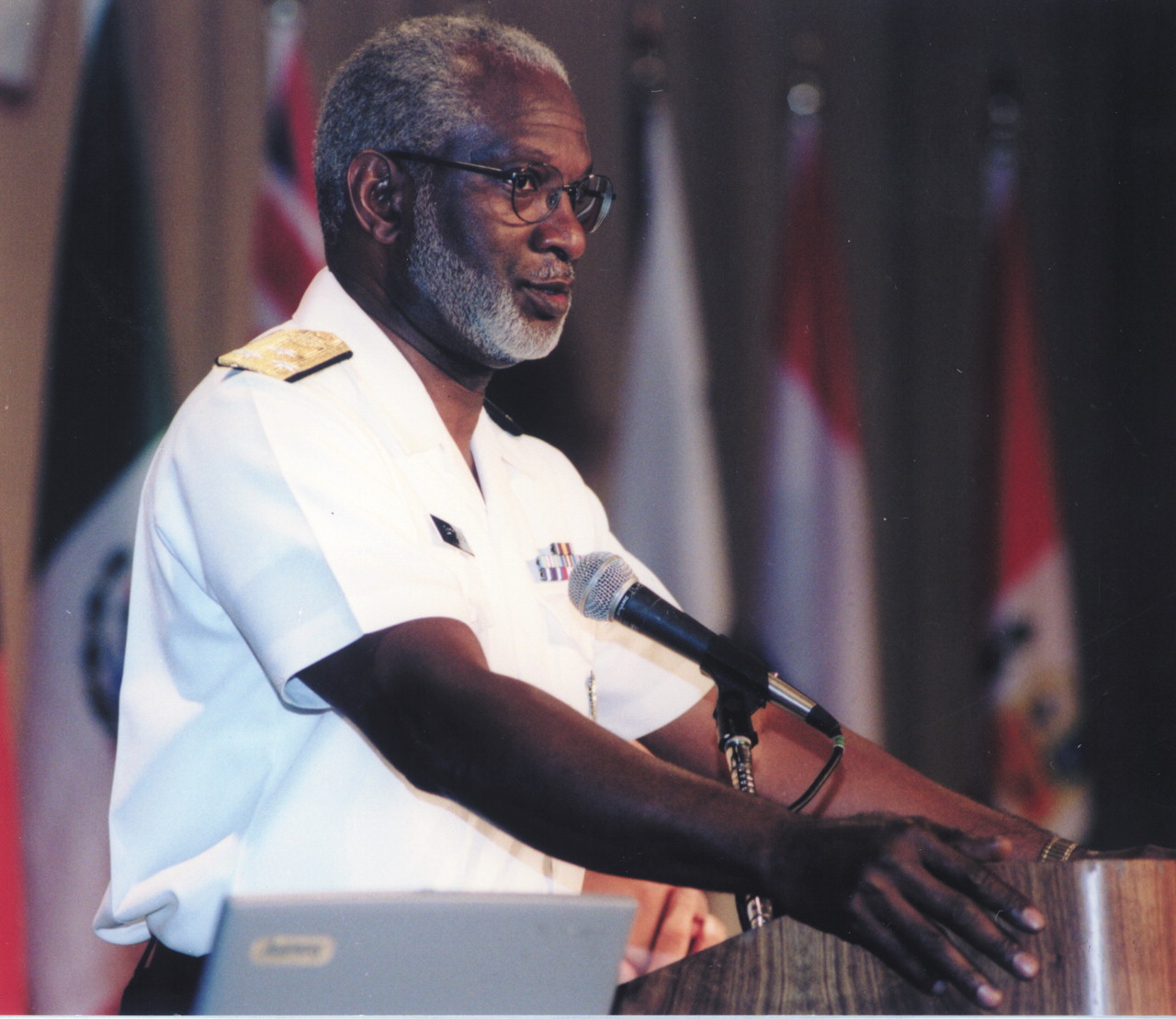

According to U.S. Surgeon General David Satcher, M.D., the first Surgeon General’s Report on Mental Health, released in 1999, was not just part of a national strategy, but a global one to improve mental health worldwide.

Satcher emphasized this point at the international plenary session of the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill’s (NAMI) 2001 Annual Convention in Washington D.C., in July.

He was speaking about a May summit of members from the World Health Assembly, who met in Geneva, Switzerland, to discuss mental health. “People from all over the world met to discuss mental health, and our report was part of that discussion,” said Satcher.

“Mental health should be supported and invested in to the same extent that we support other aspects of health,” said Satcher, who spoke to a room packed with hundreds of mental health advocates and professionals.

NAMI members from around the world, including people with mental illness, family members, and mental health professionals—as well as 100 delegates from 23 countries—gathered to hear Satcher and other panelists speak about the global impact of mental illness.

Addressing the international theme of the plenary session, Satcher told NAMI members that worldwide about 400 million people live with psychiatric or neurological disorders, including drug and alcohol abuse.

“Globally, unipolar major depression ranks fourth in disability disease burden,” said Satcher. But the news got worse. “We project that by 2020, it will rank second only to heart disease.”

Satcher also spoke out against the ever-present burden of mental illness stigma.

The Surgeon General noted that there have been people who have committed suicide who never acknowledged that they were depressed, and families who didn’t feel comfortable getting mental health treatment for their child.

“And when communities don’t make mental health services available—when there is no parity of access to treatment, and when our policies do not reflect the need for that parity, stigma is working on the community level,” said Satcher.

David Brandling-Bennett, M.D., deputy director of the Pan American Health Organization, the regional office of the World Health Organization (WHO), attributed both stigma and a lack of resources to problems on a global scale.

“Millions of people with mental illness do not have access to treatment, and beyond that, many suffer human rights violations as a result of their disabilities,” remarked Bennett.

Bennett, who has spent considerable time working in Thailand and Kenya, where he was in charge of the research and the control of tropical and vaccine-preventable diseases, used numbers to convey some alarming truths.

“We estimate that in our part of the world, particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean, the lifetime prevalence of mental disorders is 20 to 25 percent,” he said, warning that these numbers were likely to increase.

For instance, according to Bennett, the WHO projects that the number of people living with major depression worldwide is likely to rise from 20 million to 35 million in the next 20 years.

The number of people living with schizophrenia is projected to go from 3 million to 5.5 million by 2020.

To better treat people with mental illness, Bennett recommended that developing countries implement mental health policies and that advocates urge psychiatrists and mental health professionals in those countries to utilize evidence-based practice guidelines.

Bennett also urged the recognition of special populations of people with mental illness, particularly those living in rural areas, the poor, and minorities, all of whom are less likely to have access to psychiatric treatment.

Perhaps NAMI’s new executive director Richard Birkel, Ph.D., who joined Satcher and Bennett on the panel, best summed up the experiences of people living with mental illness in attendance that day.

“You’ve risen from fear, despair, and disbelief through anger, cynicism, and exhaustion,” said Birkel, “but you have returned, each time, stronger, better organized, and smarter.” ▪