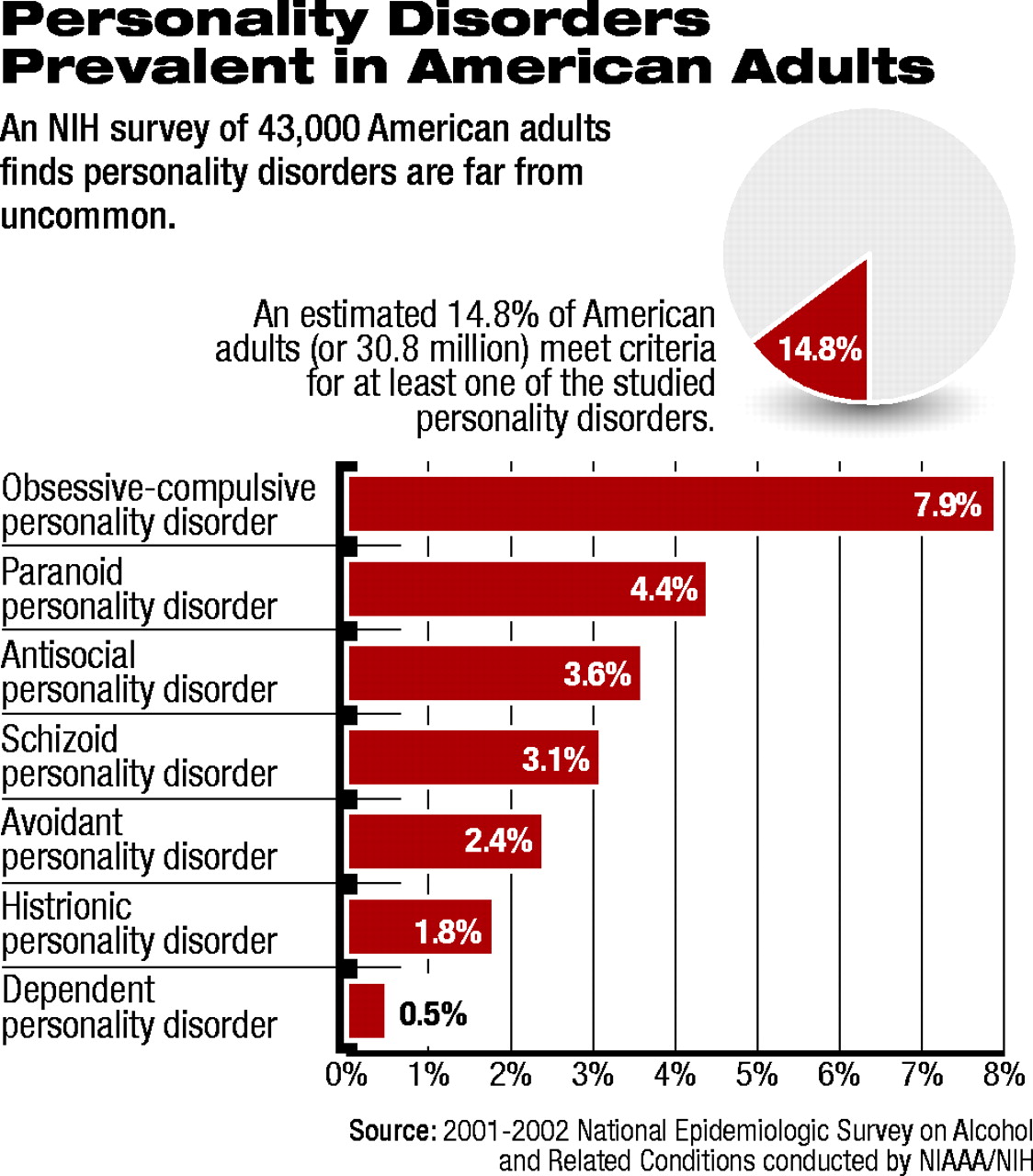

Almost 15 percent of Americans, or 30.8 million adults, meet diagnostic criteria for at least one personality disorder, according to the results of the 2001-02 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC).

Among several types of personality disorders studied, the most common personality disorder found among American adults in the large, population-based study was obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (7.9 percent, or 16.4 million people), followed by paranoid personality disorder (4.4 percent, or 9.2 million), and antisocial personality disorder (3.6 percent, or 7.6 million).

Other personality disorders affecting substantial numbers of Americans were schizoid (6.5 million), avoidant (4.9 million), histrionic (3.8 million), and dependent (1 million) (see chart).

Excluded from the study were borderline, schizotypal, and narcissistic disorders.

The results of the study appear in the July Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

“We know that these disorders often co-occur with one another and with Axis I disorders,” primary investigator Bridget Grant, Ph.D., told Psychiatric News. “We also know they affect the course, severity, and treatment compliance of substance use disorders—what we didn't know was the magnitude of [personality disorders] in the population.”

Grant said she found a great deal of comorbidity between certain personality disorders, especially avoidant and dependent, and that these data would be published in an upcoming issue of Comprehensive Psychiatry.

Grant is chief of the Laboratory Epidemiology and Biometry at the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism's (NIAAA) Division of Intramural Clinical and Biological Research.

The sample researchers used for the 2001-02 NESARC was based on the sampling frame of the Census 2000/2001 Supplemental Survey.

Approximately 1,800 lay interviewers with the U.S. Census Bureau administered the NESARC instrument to 43,093 adults aged 18 and older to assess the prevalence and comorbidity of a number of mental illnesses.

As part of the survey, interviewers asked respondents a series of questions about how they felt or acted most of the time throughout their lives“ regardless of the situation or whom they were with,” according to the report.

Interviewers used the NIAAA Alcohol Use Disorder and Associated Disabilities Interview Schedule–DSM-IV Version (AUDADIS) as part of the study. In order to receive a personality disorder diagnosis, respondents had to experience the requisite number of symptoms listed in DSM-IV for a personality disorder, and at least one of those symptoms must have caused the person to experience social and/or occupational dysfunction.

Grant tested respondents for the following personality disorders: avoidant, dependent, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, histrionic, and antisocial, but excluded borderline, schizotypal, and narcissistic personality disorders due to the large number of symptom items required to diagnose those disorders. The researchers decided to include the latter three personality disorders in another phase of the study.

She also examined the relationship between personality disorders and emotional and social functioning by using the Short Form 12, Version 2 questionnaire.

Grant found that a number of personality disorders—specifically, avoidant, dependent, paranoid, schizoid, and antisocial personality disorders—were associated with significant emotional disability problems with social functioning, and occupational impairment.

However, having obsessive-compulsive personality disorder did not correlate with higher disability scores. According to the article, “these findings suggest that many individuals who demonstrate the preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and mental and interpersonal control characteristic of the disorder may be high functioning even in the absence of flexibility, openness, and efficiency.”

Since Grant conducted the study among a randomly selected population-based sample, the prevalence rates from her study diverged from those presented in the DSM-IV-TR in some cases.

For instance, according to the DSM-IV-TR, dependent personality disorder is “among the most frequently reported personality disorders encountered in mental health clinics,” the study report pointed out. However, Grant's study found it to be the least common in the population.

In addition, the DSM-IV-TR estimates that the prevalence of avoidant personality disorder in the general population is between 0.5 percent and 1 percent, yet Grant found it to be 2.36 percent.

Grant explained that prevalence estimates of various personality disorders in the DSM are based on relatively small, clinical studies of patients who are receiving mental health services on an inpatient or outpatient basis.

“You can run into problems if you rely solely on clinical samples,” she said. “If you want to know the true prevalence of a certain disorder, you have to get out of the clinic.”

Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., executive director of the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education and director of APA's Office of Research, said he agreed that “prevalence rates for any disorder are best obtained from community samples,” and when such samples were available—for prevalence rates associated with most Axis I disorders and antisocial personality disorder—they were included in the DSM-IV-TR.

However, Regier suggested that researchers test the validity of the AUDADIS more thoroughly by having clinicians diagnose a sample of the same community subjects diagnosed by lay interviewers using the AUDADIS.

He also stressed the importance of conducting additional population-based studies on prevalence rates of personality disorders before including such data in future DSM revisions.

In her analyses, Grant identified subgroups of the population that are at higher risk than others for having certain personality disorders. For instance, according to the article, Native Americans are 1.6 times more likely to have avoidant personality disorder than are whites. Blacks, Native Americans, and Hispanics are at greater risk for paranoid personality disorder than are whites.

In addition, being poor, divorced, or widowed are among the risk factors for a number of personality disorders.

An abstract of the article, “Prevalence, Correlates, and Disability of Personality Disorders in the U.S.: Results From the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions,” is posted online at<www.psychiatrist.com/>.▪