There is currently no easy way to prevent weight gain caused by second-generation antipsychotics such as olanzapine, clozapine, and risperidone. But researchers may have identified a drug that may halt antipsychotic-provoked weight gain after it has started. The drug is amantadine.

Amantadine is a dopamine agonist approved for treatment of influenza A virus, idiopathic parkinsonism, and the extrapyramidal side effects of antipsychotic medications. Since previous studies have shown that weight loss is a side effect of amantadine, Karen Graham, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the University of North Carolina, and colleagues decided to undertake a small pilot trial to determine whether amantadine could halt weight gain in subjects who had gained weight while using a second-generation antipsychotic.

Twenty-one adults who had taken the second-generation antipsychotic olanzapine for one to 44 months and who had gained between five and 58 pounds while on it were randomly assigned to receive up to 300 mg/day of amantadine or a placebo in addition to olanzapine for 12 weeks. Subjects' body mass indices and positive and negative symptoms were assessed at baseline and at 12 weeks.

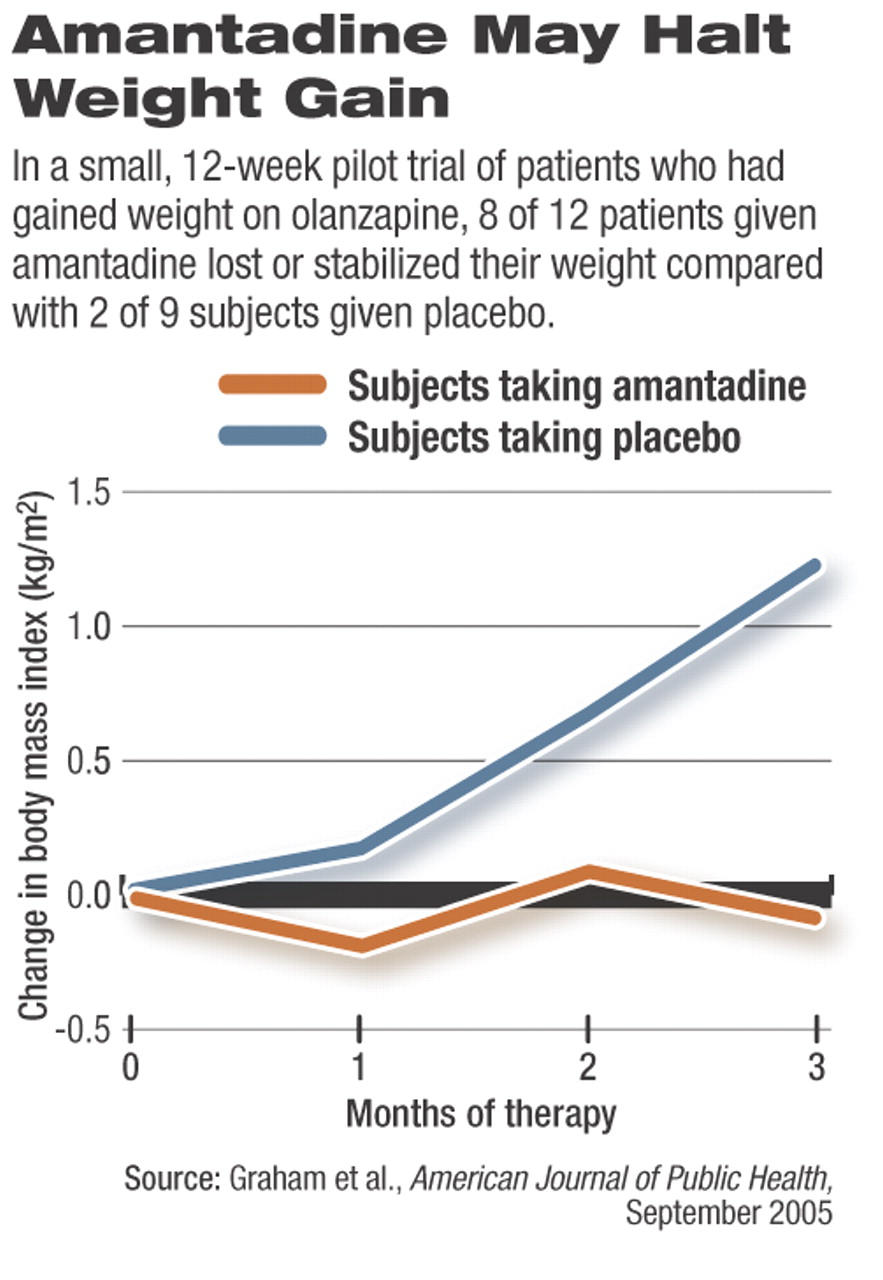

Twelve subjects were taking the amantadine, and eight of them either stabilized their weight or lost weight, whereas only two of the nine placebo subjects did.

The amantadine group lost an average of 0.8 pounds and reduced their body mass index by an average of 0.07 kg/m2, whereas the placebo group gained an average of 8.7 pounds and increased their body mass index by an average of 1.24 kg/m2.

Moreover, the positive and negative symptoms of subjects taking amantadine did not worsen over the course of the study, suggesting that the drug was not aggravating their psychosis.

Thus, it looks as if amantadine might be able to halt weight gain in some patients taking a second-generation antipsychotic and may do so without causing adverse psychological effects, Graham and her team concluded in the September American Journal of Psychiatry.

The challenge now, Graham told Psychiatric News, is to see whether amantadine can keep individuals placed on a second-generation antipsychotic from gaining weight in the first place. She and her group are currently conducting such a study.

Yet even if their results are positive, she cautioned, amantadine will probably not be a “magic bullet” to prevent weight gain in patients on second-generation antipsychotics.

The reason, she explained, is that “the causes of weight gain will be varied and will depend on the medication in question and characteristics of the individual patient. The second-generation antipsychotics act on a number of neurotransmitters, which influence appetite, satiety, spontaneous and volitional activity, and the ability of our bodies to store or burn energy. For any given combination of patient and medication, one or more of these may promote weight gain.”

Moreover, she added, “Obesity is steadily increasing in the United States and many other countries and has reached alarming rates. Our patients are living in a sedentary culture, where access to cheap calorie-dense, nutrient-poor food is much greater than it is to fresh fruits and vegetables. We need to address these societal issues as well as look for pharmacologic means to help people reach and maintain a healthy weight.”

The mechanism by which amantadine thwarts weight gain is unknown. But it may decrease appetite through its dopaminergic anorexic effects.

The study was financed by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and an unrestricted gift from Eli Lilly and Co., maker of olanzapine.

Am J Psychiatry 2005 162 1744