Just as American mental hospitals have downsized or closed since the mid-20th century, the same trend has occurred throughout Europe. Europeans with severe mental illnesses have had an advantage during these decades, however, that Americans with severe mental illnesses have not had—the establishment of comprehensive community mental health services to compensate for the loss of institutionalized care.

Nonetheless, a new era of reinstitutionalization of the seriously mentally ill may have begun in Europe, a study reported in the November 26, 2004, British Medical Journal suggests. Reinstitutionalization in the study is defined as placement in residential care or supported housing or in prison.

The investigation was headed by Stefan Priebe, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of social and community psychiatry at Queen Mary University of London. The study team also included Durk Wiersma, M.D., a professor of clinical epidemiology of psychiatric disorders at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, and other researchers.

Priebe and his coworkers had reason to believe that a new era of reinstitutionalization for gravely mentally ill individuals might be beginning in Europe because of isolated reports on the subject. They decided to investigate the issue in England, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, and Sweden because these countries had experienced major mental health reforms involving deinstitutionalization since the second half of the 20th century; had fairly reliable data on mental health care; and represented different traditions of mental health care, including Scandinavian, central European, and Mediterranean.

They collected data from the six countries on conventional psychiatric hospital beds (beds provided by psychiatric departments in public or private hospitals; only a tiny minority of these beds are still long term for patients with chronic disorders); involuntary hospital admissions; the number of places in residential care or supported housing (which, while often regarded as an alternative to psychiatric hospitals and a form of deinstitutionalization, still constitute a form of institutionalization as defined by bricks and mortar); forensic beds, and the general prison population. For each of these categories, they investigated how numbers have changed since 1990.

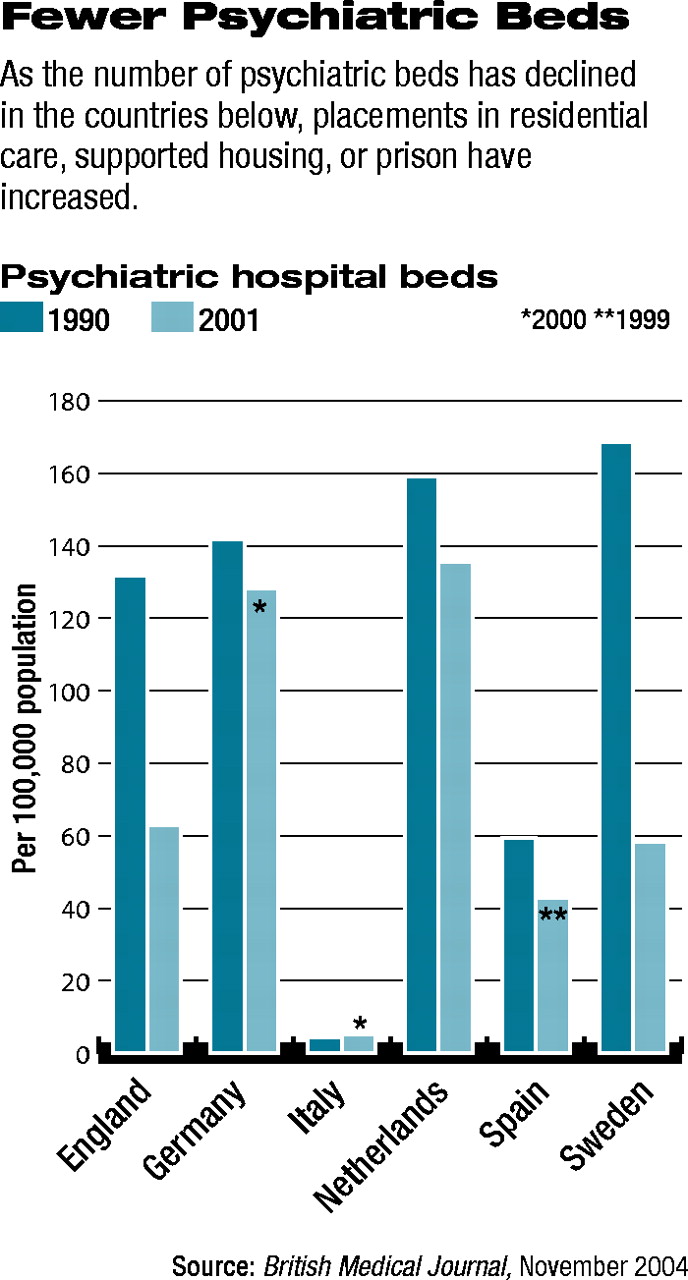

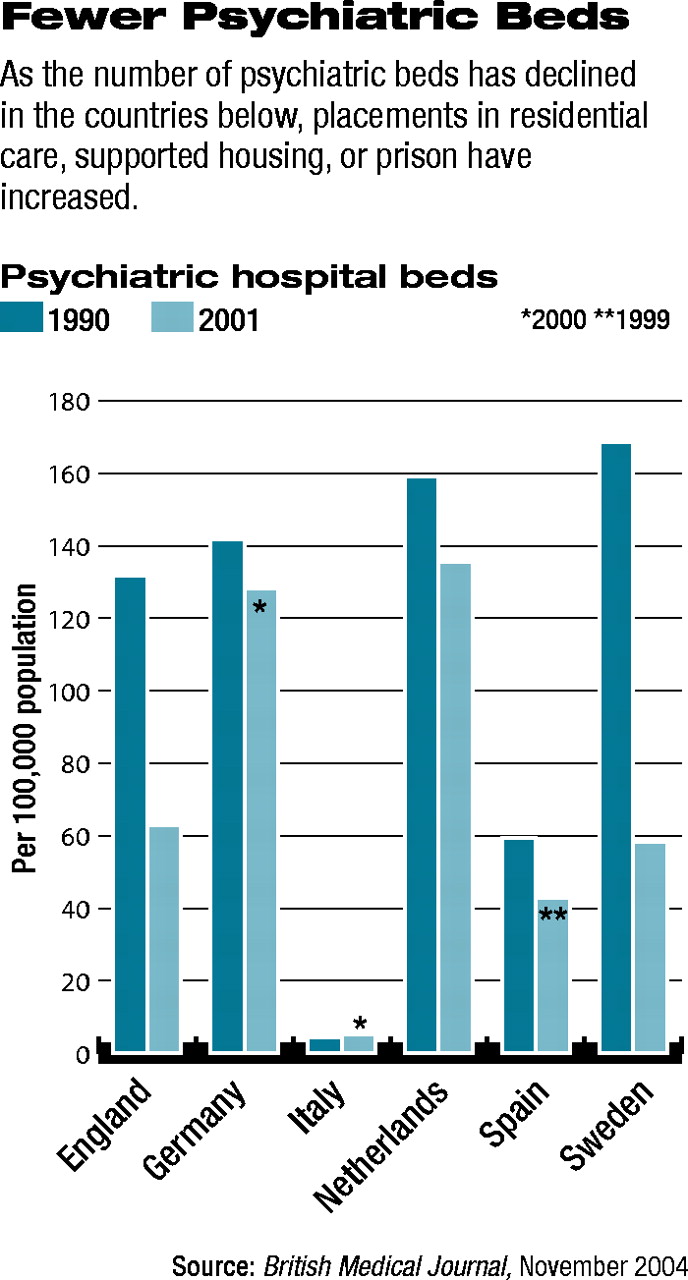

Many Psychiatric Beds Eliminated

They found that the number of conventional psychiatric hospital beds has been reduced in five of the six countries—Italy is the exception—and that changes in involuntary hospital admissions have been inconsistent (they have risen in England, the Netherlands, and especially Germany, but have fallen slightly in Italy, Spain, and Sweden). In contrast, places in residential care or supported housing have increased in all six countries (from 15 percent in Sweden to 259 percent in Italy). The number of forensic beds has also increased (from 10 percent in Italy to 143 percent in the Netherlands), and so has the size of the general prison population (from 16 percent in Sweden to 104 percent in the Netherlands).

Thus, “reinstitutionalization [as defined by placement in residential care or supported housing or in prison] is taking place in European countries with different traditions of health care,” they concluded,“ although with significant variation between the six countries studied.” In the Netherlands, for example, the number of conventional psychiatric hospital beds has not changed much during the past few years, Wiersma told Psychiatric News. “The increase of forensic psychiatric beds is real, but concerns a rather small number of patients,” he added. “I doubt whether this will last.”

Risk Containment May Explain Trend

Reasons for the apparent trend in reinstitutionalization remain to be documented. However, Wiersma doubts whether it is due to an increase in cases of severe mental illness. “Personally, I think that the most important factor is a changed societal tendency toward risk containment and security as indicated by the rising general prison population,” Priebe said in an interview. “In the history of psychiatry, there have repeatedly been major shifts that had little to do with scientific evidence or new developments within psychiatry, but were rather due to overall societal processes.”

In the event that such a reinstitutionalization trend is really occurring, it shows “the need for a professional and public debate about the ethical principles and, more importantly, specific values that underpin our work in mental health care,” Priebe asserted. “If nothing happens, more and more funding will go into new institutions.... Also, it may lead to a stronger split between mental health care for those who can actively seek treatment and pay for it and mental health care for severely mentally ill patients who would be subjected to a second class of institutionalized care.”

While Priebe is not aware of any study to explore the phenomenon of reinstitutionalization in the United States, he believes that it might be a worthwhile undertaking. “However, one should keep in mind that in the United States, there are seven times as many people in general prisons as in the average European country, and many of them suffer from mental illness. Thus, an American study would probably have to pay particular attention to the proportion of mentally ill people who are kept in prisons.”

The study was funded by the East London and the City Mental Health Trust.