His name is “Jeff”; he is age 25 and a likeable fellow. The problem is that he has a speech impediment, so it's hard to understand what he says. It is possibly because of this problem that he has never asked a girl for a date.

Jeff is not alone. A new longitudinal study out of Canada, and in press with the Journal of Anxiety Disorders, has found that youngsters with speech and language problems are three times more likely to suffer from social anxiety (social phobia) at age 19 than are youngsters without such problems.

This finding is valuable because little has been known about the origins of social anxiety, even though it is one of the most common mental health problems (Psychiatric News, December 17, 2004).

Studies have already revealed that children with speech/language problems often have trouble interacting with peers, are often viewed as undesirable playmates, and are frequently rated by teachers as having poor social skills. But no one appeared to have examined whether early speech/language difficulties might lead to social phobia later in life. So Joseph Beitchman, M.D., clinical director of the Child, Youth, and Family Program at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto, and his coworkers decided to conduct a prospective study to find out.

In 1982, some 1,700 5-year-olds in the Ottawa-Carleton region of Ontario were screened for speech/language competency. Of those, 142 who were found to be speech and/or language impaired agreed to take part in the study. Another 142 children without speech/language difficulties served as controls. The controls were the same age and gender as the impaired children and from the same schools.

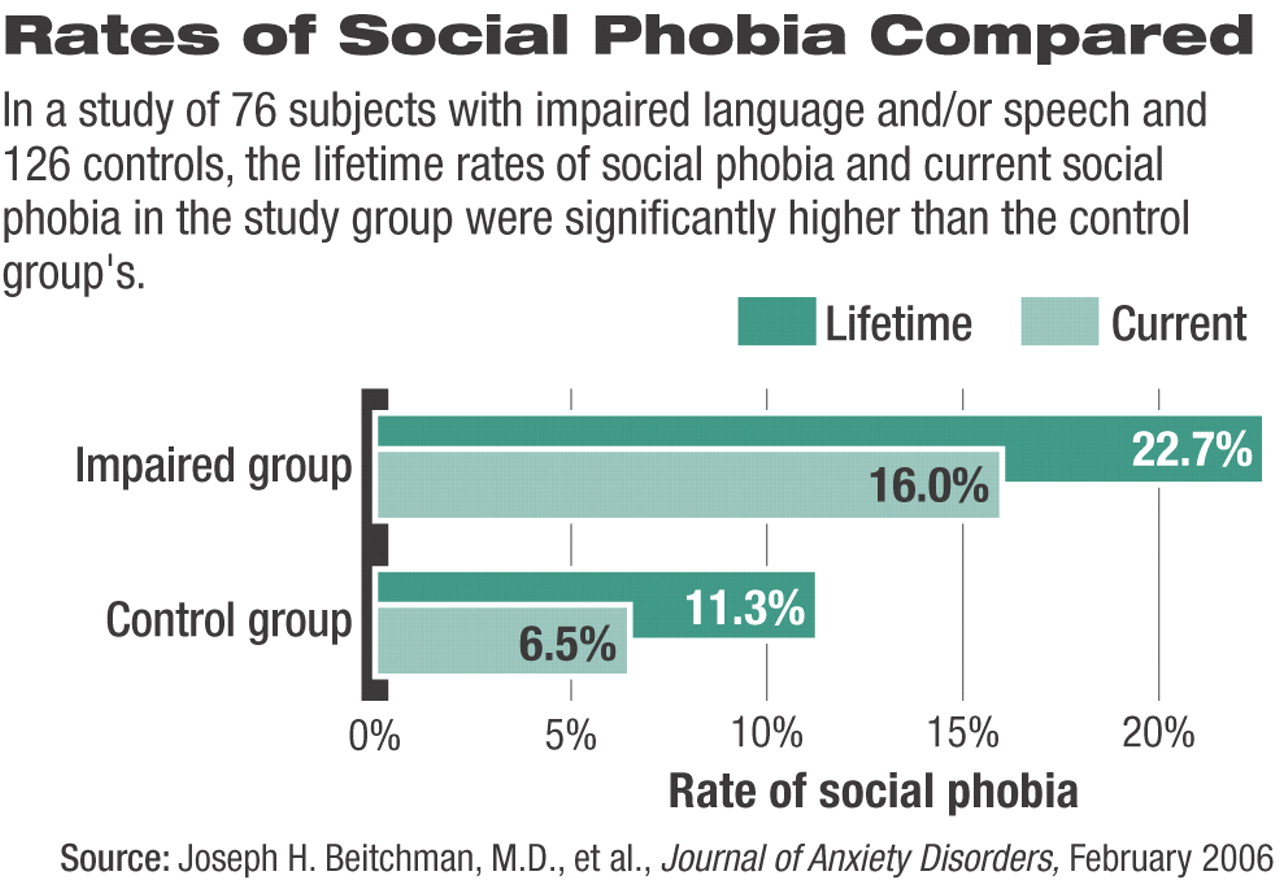

When the 284 subjects were 19 years old, 258 (90.8 percent) agreed to take part in the second follow-up study. Data about the social fears of 240 of the 258 were obtained. Due to the small number of speech-impaired-only subjects with social phobia, Beitchman and his coworkers decided to compare social fear results for just two groups—76 who were language or language/speech impaired and 126 controls.

Significant Differences Found

Sixteen percent of the impaired subjects were found to have social phobia at follow-up, while only 7 percent of the control subjects did, and the difference was statistically significant. This 16 percent one-year prevalence rate is “one of the highest rates of social phobia” ever reported, the investigators indicated.

Further, 23 percent of the impaired subjects met criteria for a lifetime prevalence of social phobia, compared with only 11 percent of the controls—also a significant difference.

And compared with controls, individuals who had been impaired at age 5 were also three times more likely to experience social anxiety at age 19.

Moreover, the mothers of both impaired subjects and control subjects had been assessed for social anxiety when the subjects were 5 years old. A significant link was later found in control subjects, but not in impaired subjects, between having a socially anxious mother and having social anxiety itself.

Finding Surprises Researchers

Beitchman was not surprised that speech/language impairment and social anxiety were strongly linked, he told Psychiatric News. But what did surprise him, he said, “was that there appear to be two routes to social phobia—one through a family history of anxiety and a second through a history of language impairments.”

The findings have implications for preventing mental illness, the researchers suggested. For instance, if early speech/language difficulties are a risk factor for later social phobia, then perhaps children with such problems should receive help in developing social skills.

The results also have implications for clinical psychiatrists, Beitchman added. “They need to be aware of this [speech/language impairment] route to social phobia and engage [patients who have developed social phobia via this route] in appropriate strategies to address their concerns.”

“This is one of the strongest longitudinal studies of its kind, in that 90 percent of subjects initially studied were retained for reassessment,” Claudio Toppelberg, M.D., told Psychiatric News. Toppelberg is a child psychiatrist at Children's Hospital Boston and Harvard Medical School and director of child language and developmental psychiatry at Judge Baker Children's Center.

“While this research cannot directly address issues of causality and etiology—a limitation shared by other naturalistic developmental epidemiology research,” Toppelberg continued, “the results are consistent with a well-supported account indicating that early language impairment leads to maladaptation and to clinical and subclinical psychopathology down the road. One issue that the study does not address is the potential link with selective mutism, which is known to be associated with language impairment in children and predictive of social phobia in adults.

“The presence of language impairment or its sequelae needs to be considered when working clinically with socially phobic and other adult patients, as language impairment can greatly affect the effectiveness of therapy and perpetuate the functional impairment, thus magnifying the burden of these disorders.”

The study was funded by Health Canada, National Health and Research Development Program.

An abstract of “Social Anxiety in Late Adolescence: The Importance of Early Childhood Language Impairment” can be accessed at<www.sciencedirect.com> by clicking on “Browse A-Z of Journals,” “J,”“ Journal of Anxiety Disorders,” and “Articles in press.” ▪