The N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, memantine, appears to provide significant benefits to patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease for as long as one year, researchers said last month.

The new data come from a 24-week open-label extension study that followed a 28-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of memantine in 252 patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's. The new report appeared in the January Archives of Neurology. Data from the double-blind, first phase of the study were published in the April 3, 2003, New England Journal of Medicine (Psychiatric News, May 2, 2003).

“This study demonstrates that it is possible to alleviate some of the cognitive and functional losses associated with the later stages of Alzheimer's, providing a basis for greater optimism on the part of caregivers,” said principal investigator Barry Reisberg, M.D., in a press release. Reisberg, a professor of psychiatry at New York University (NYU) School of Medicine, was the lead author of both reports.

Both phases of the study were funded by the German company Merz Pharmaceutical GmbH, which developed the drug and markets it worldwide outside the United States. Memantine is marketed as Namenda in the United States by Forest Pharmaceuticals.

“Our study verifies that this medication continues to be beneficial and is safe, with remarkably few side effects,” added Reisberg, who is also the director of the Silberstein Aging and Dementia Research Center at NYU.

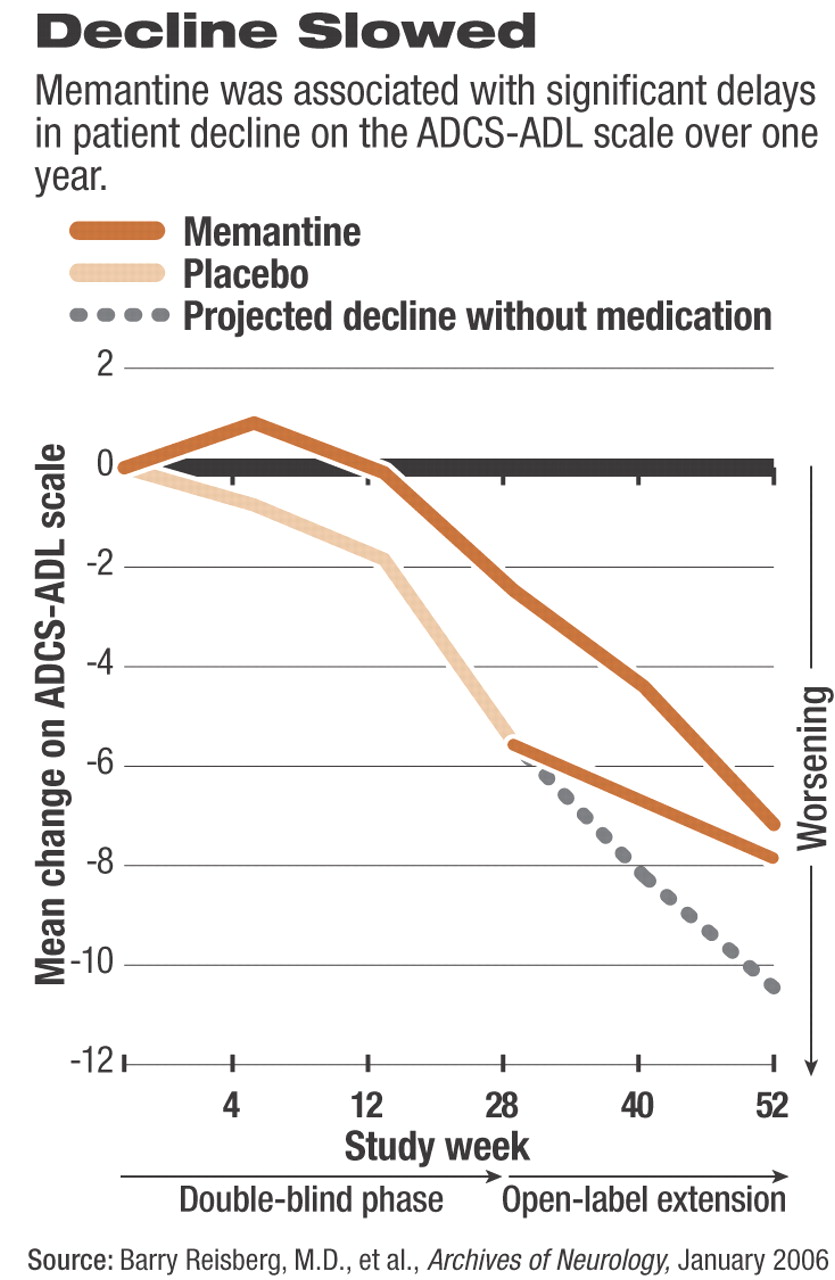

The researchers used the same primary efficacy measures during both phases of the study: change in patients' scores on the 19-item Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study–Activities of Daily Living Scale, modified for severe dementia (ADCS-ADL), and the New York University version of the Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change plus caregiver input (CIBIC-Plus).

Reisberg and his colleagues previously reported that memantine significantly slowed the rate of decline in patients who took the drug for the first 28 weeks of double-blind therapy, compared with those taking placebo. In fact, ADCS-ADL scores for those taking memantine signaled a small but statistically significant improvement during the first four weeks of the first phase of the study (see

chart).

During the open-label phase of the study, the patients who were switched from placebo to memantine for the remaining 24 weeks exhibited a significantly slower rate of decline in ADCS-ADL scores compared with their mean rate of decline while taking placebo during the double-blind phase. However, for patients who were taking memantine during the first 28 weeks and continued to take the drug for the remaining 24 weeks of open-label therapy, the rate of decline in scores on the ADCS-ADL increased, especially in the final 12 weeks (weeks 40 through 52) of the study.

Switching to memantine at week 28 was also associated with a significantly decreased rate of decline in scores on the CIBIC-Plus compared with the mean rate of decline for placebo during the double-blind period.

Overall, the most commonly reported adverse events associated with memantine during the open-label phase of the study were consistent with what patients had experienced during the double-blind phase: agitation, insomnia, and urinary tract infection.

In an accompanying Archives of Neurology editorial, Jeffrey Cummings, M.D., a professor of neurology at the University of California at Los Angeles who was not involved in the study, wrote, “Overall, the data suggest that long-term memantine therapy is safe, with no excess of serious adverse events occurring in the treatment group.” Cummings added,“ Two out of three measures suggest that memantine continued to exert beneficial effects for months six through 12 of therapy.”

Arch Neurol 2006 63 49