When its deceptively simple findings were first revealed early last month, the report detailing the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) gargantuan meta-analysis on the risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adults who took part in antidepressant clinical trials was met with a wide range of reactions, not the least of which was initial disbelief and some lack of understanding (see

page 1).

The analysis had been promised for over two years, but was posted on the FDA's Web site only seven days before the December 13, 2006, meeting of the agency's Psychopharmacologic Drugs Advisory Committee (PDAC).

Researchers at the federal agency, in fact, had completed two separate, mostly parallel, analyses of the same dataset: the patient-level adverse-event data from nearly 100,000 adults who took part in 372 industry-sponsored, double-blind, randomized, controlled clinical trials of antidepressant medications.

Both analyses led to similar conclusions: risk was related to age, with patients in some age groups at higher risk and patients in other age groups at lower risk. In general, the younger the subjects were, the higher was the risk.

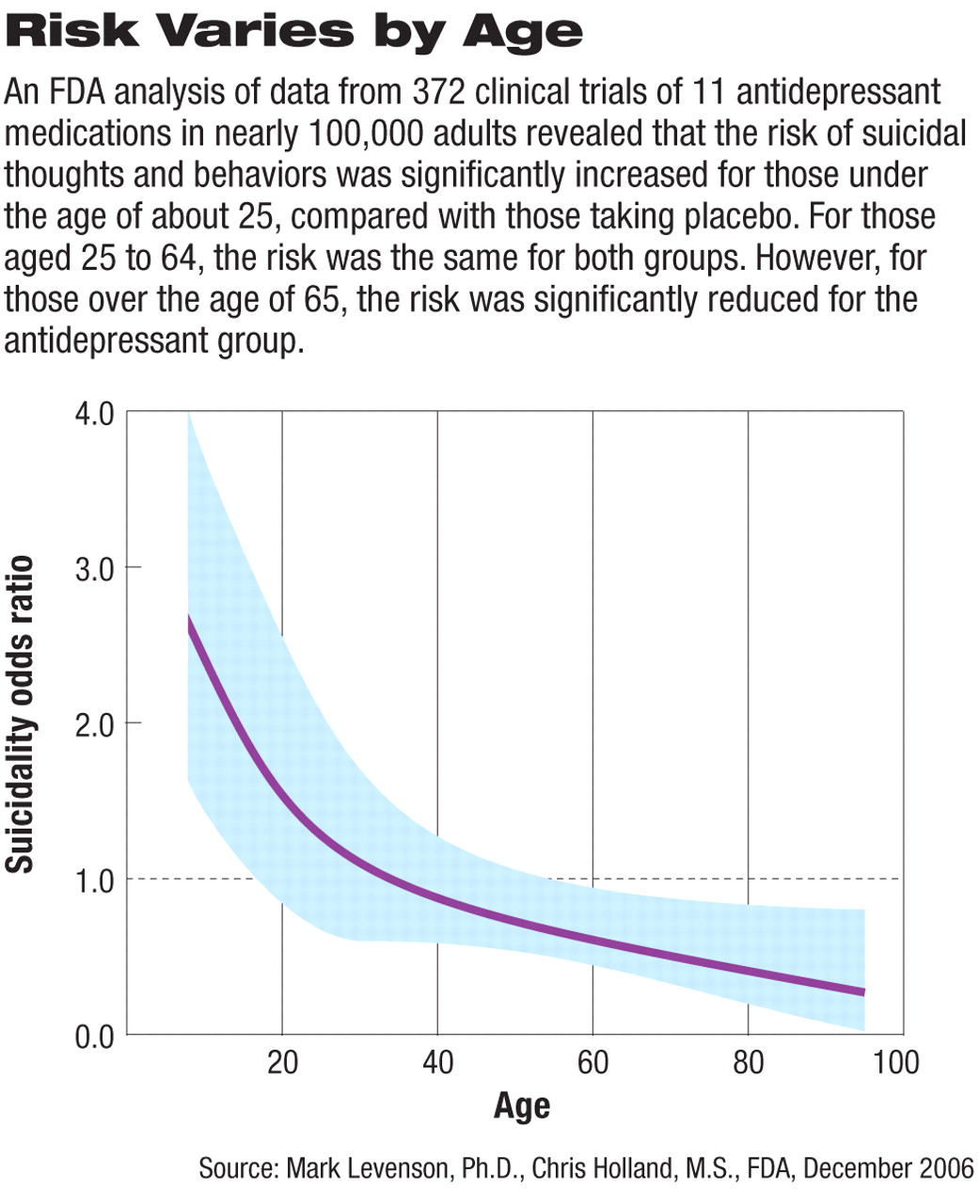

While the age ranges varied slightly in the two analyses, the trend was evident: children and adolescents taking antidepressants were two to three times as likely to experience “suicidality” as those on placebo—confirming the results of the 2004 FDA/Columbia University analysis (Psychiatric News, October 15, 2004). Then as age increased, risk decreased, and at some point around age 25 to 35, the odds of experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors were the same as those for people who were not taking an antidepressant (with the odds ratio equaling 1.00; see graph at right).

Moreover, for those over age 65, a clear “protective effect” was seen, that is, older patients taking antidepressants in the clinical trials had a significantly lower risk of suicidal thoughts or behaviors compared with patients taking placebo.

Experts Crunch Mountain of Data

The complexity involved in completing the meta-analysis project, particularly the agency's decision to complete two analyses, appears to be the chief reason the final report was so long in the making.

Both analyses looked at adverse-event data on 99,839 patients who were randomly assigned to one of 11 antidepressants or to placebo in 372 double-blind clinical trials, all sponsored by pharmaceutical companies. The majority (295 of the 372 trials, or 79.3 percent) involved patients with“ psychiatric indications” (which included major depressive disorder, other affective disorders, and “other psychiatric disorders”). The remainder of the clinical trials studied the use of antidepressant medications for “behavioral disorders” (43/372, or 11.6 percent) or “other disorders” (34/372, or 9.1 percent).

The analyses were completed by Marc Stone, M.D., and Lisa Jones, M.D., M.P.H., medical reviewers in the FDA's drug safety group, and Mark Levenson, Ph.D., and Chris Holland, M.S., medical statistical experts in the FDA's Office of Biostatistics. All four were part of the agency's “adult suicidality working group,” noted Thomas Laughren, M.D., director of the FDA's Division of Psychiatry Products, in his briefing memo to the advisory panel members.

Laughren explained that while both analyses were part of a collective, cooperative effort, they grew out of “different perspectives” on how best to crunch so much data.

“Since these were exploratory analyses,” Laughren wrote to PDAC members, “in the sense that assessing the effect of drugs on suicidality was not a prespecified primary activity for any of these trials, we considered it appropriate to permit parallel analysis efforts to proceed along somewhat different paths for this common dataset. In fact, we were gratified to find that the results for these slightly different analytical approaches were substantially the same, as were the conclusions. We feel that the finding of overlapping results from different methods serves to strengthen the results and conclusions.”

FDA Details Its Findings

In the end, the agency's experts analyzed the data many different ways, including by specific diagnosis; by “psychiatric indications” versus other diagnoses; by age, gender, and race; and by the type of drug (SSRI versus non-SSRI).

The primary endpoints were completed suicide, suicide attempt, preparatory acts, and suicidal ideation. These categories mirrored those used in the 2004 FDA/Columbia University pediatric antidepressant/suicidality analysis. However, the “potentially suicide-related adverse events” identified in the 372 adult clinical trials were reviewed for accuracy and validity by internal FDA staff, rather than the Columbia University experts who had validated the pediatric adverse event data.

Regardless of the methodology used to analyze the dataset, the FDA reported that the “age-related” trend remained the only robust and statistically significant differentiating factor to explain which patients were at particular risk. But, Stone and Jones cautioned in their report, the“ age-related trend—increasing age associated with decreasing risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviors—in theory must be a proxy for a complex interplay of factors, including those of physiological, psychological, and potentially environmental origin, all of which remain at this point unknown.”

“There were no notable differences between test-drug subjects and placebo subjects in age, gender, race, baseline history of suicide attempts, baseline history of suicidal ideation, or treatment exposure [SSRI versus non-SSRI],” Levenson and Holland concluded in their PDAC presentation.

FDA's Stone, during his presentation to the panel that morning, emphasized,“ The observed relationship between suicidality, age, and antidepressant treatment appears not only in [subjects with] major depressive disorder, but in all subjects with psychiatric diagnoses.” One could interpret this finding, he added, as indicating that “[t]here is nothing different in the psychopharmacology of suicide versus the psychopharmacology of depression or another illness—the suicide factor is independent of actual diagnosis.”

Finding the Bottom Line

If psychiatrists, other physicians, and mental health professionals want to explain the overall findings on a level that patients and family members can understand, Levenson noted during the PDAC meeting, they might find it easiest to “use the calculation of risk difference.”

Risk difference, he explained, “is simply asking the question: How many additional patients—out of 1,000—would you expect to see experience suicidal behavior and/or ideation as a result of taking antidepressant medication?”

From the pediatric data, Levenson said, the answer is 14 out of 1,000 patients under age 18; for those aged 18 to 24, it's 4; and for those aged 25 to 30, it's none— that is, patients in this age group taking an antidepressant are no more likely to experience suicidal thoughts or behaviors than those not taking such medications.

For patients aged 31 to 64, two fewer patients would likely experience suicidal thoughts/behaviors. For those aged 65 and over, he concluded, “taking an antidepressant prevented 6 patients out of 1,000 from experiencing suicidal thoughts or behaviors.”

The FDA antidepressant suicidality analysis and other PDAC meeting materials are posted at<www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/06/briefing/2006-4272b1-index.htm>.▪