Mental health and substance abuse parity for children enrolled in managed insurance plans can improve financial protection for the insured children's families without increasing total spending for behavioral health care costs.

That was the finding from a comparison of seven federal health plans in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program (FEHBP) that had instituted parity coverage with a matched set of plans that did not have comparable coverage for mental health and substance abuse coverage.

Care for children in three of the seven federal plans showed statistically significant reductions in out-of-pocket spending that were attributable to the parity policy. In the remaining four plans, out-of-pocket spending also decreased, though the decline was not statistically significant.

“The parity policy reduced out-of-pocket spending, offering more insurance protection for those who use services,” psychiatrist and principal investigator Howard Goldman, M.D., Ph.D., told Psychiatric News. “Managed care might explain some of this, since the federal plans—but not the comparison plans—did increase their use of management techniques, such as use of written treatment plans and networks with negotiated prices. But there was little or no outright denial of care that was reported.”

Goldman is a professor of psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine and editor in chief of the APA journal Psychiatric Services.

The report was published in the February 2 Pediatrics. The lead authors were Susan Azrin, Ph.D., of Westat, a research corporation in Rockville, Md.; and Haiden Huskamp, Ph.D., and Vanessa Azzone, Ph.D., of the departments of Health Care Policy and Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. Researchers from six other institutions also participated in the study. A similar study of the effect of parity on utilization and out-of-pocket spending in adults appeared originally as a government report (Psychiatric News, September 16, 2005) and was later published in the March 30, 2006, New England Journal of Medicine.

Beginning January 1, 2001, the Office of Personnel Management required all FEHBP plans to adopt a parity policy for mental health and substance abuse treatment services defined as coverage that is “identical with regard to traditional medical care deductibles, co-insurance, copays, and day and visit limitations.” The parity benefit was available to those who used“ in-network” providers.

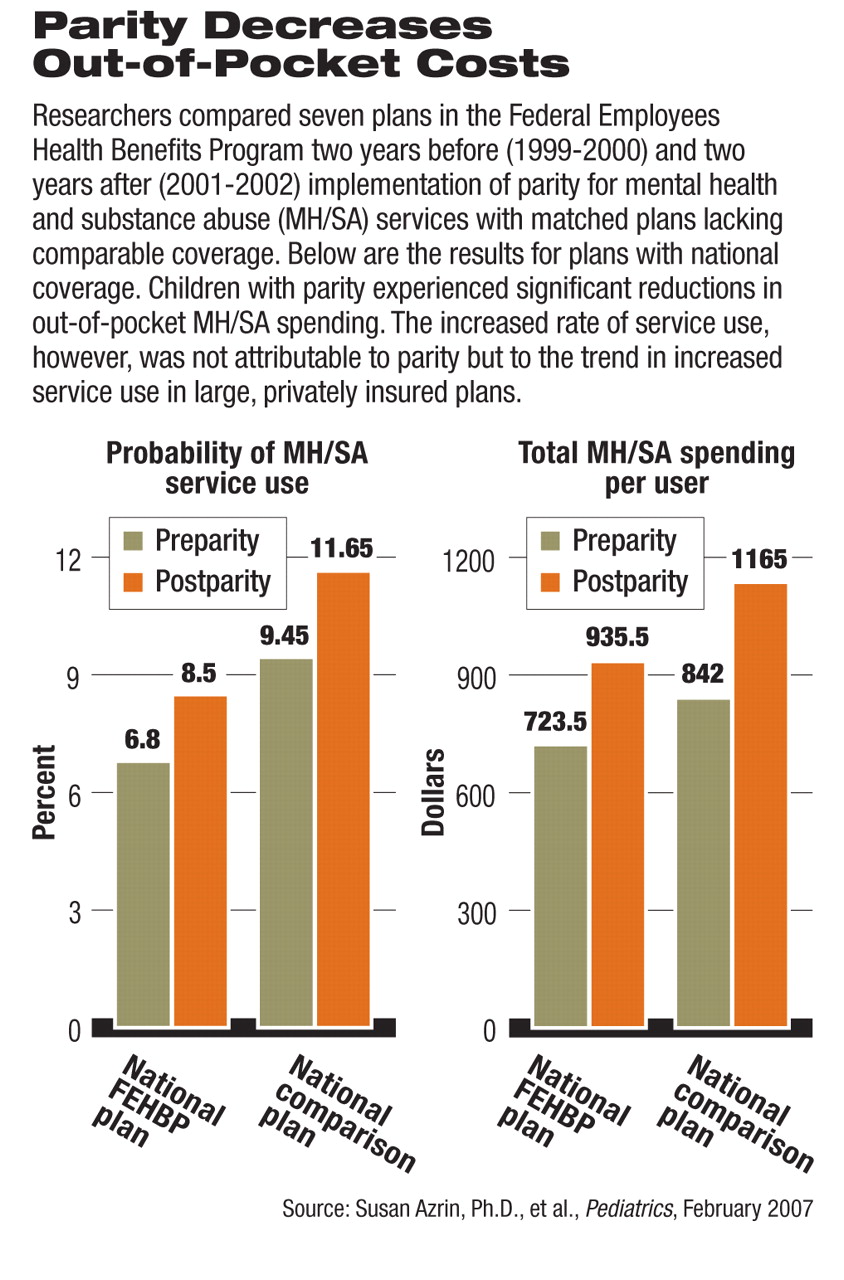

In the Pediatrics study, researchers compared service use and spending in seven of those plans during 1999-2002 with a matched set of comparison plans that did not experience a similar change in mental health and substance abuse coverage.

The comparison plans, derived from Medstat's MarketScan database, represented large self-insured employers. The FEHBP plans were selected based on location, differences in plan type and structure, size of enrollee population, and the plan's interest in collaborating.

Since increases in mental health and substance abuse service utilization were observed in both the federal plans with parity and self-insured plans without parity, researchers in the Pediatrics study used a biostatistical method known as “difference in difference” analysis to determine if increases in utilization in the federal plans could be attributed to the parity policy.

They found that the apparent increase of service use was not due to parity, but was due almost entirely to the general trend of increased use of mental health and substance abuse services—a finding that could be interpreted as disappointing by advocates who expect parity to enhance access to (and hence utilization of) services.

But Goldman emphasized that protection against catastrophic financial loss—not access—is the purpose of insurance and that the decrease in out-of-pocket spending per enrollee despite rising service use is encouraging.

Children using mental health services in the federal parity plans experienced reductions in out-of-pocket spending attributable to parity. In three plans, the reduction was statistically significant, with service users saving on average between $62.25 and $200.22 more each year than service users in the comparative plans.

“It is clear that out-of-pocket spending did decrease in most of the federal plans compared to the nonfederal plans as a consequence of parity,” Goldman told Psychiatric News. “Parity helps to lower those out-of-pocket costs even if it doesn't encourage more use or spending.”

Child psychiatrist and APA Trustee-at-Large David Fassler, M.D., who is chair of APA's Task Force on Parity, called the results “interesting and instructive” for APA's advocacy efforts on parity.

“This is one of the few studies to focus specifically on the impact of parity on children,” he told Psychiatric News.“ Consistent with previous findings, the authors demonstrated that full parity for mental health and substance abuse treatment can be implemented without an increase in overall expenditures. In fact, significant reductions in cost were identified in several of the plans studied.

“However, the study also found that with limited exceptions, parity does not automatically translate into increased access for children and adolescents with psychiatric and/or substance abuse disorders,” Fassler said. “As the authors noted, this is most likely due to the simultaneous implementation of managed care in a majority of the plans.

“While parity remains an important public policy goal, it should not be viewed as a panacea in terms of access to care,” he continued.“ Implementation of any parity legislation must be monitored closely, with active and ongoing involvement from advocacy and professional organizations.”