Exposure to severe life stressors can trigger depression, scientists have known for decades. But many persons who experience setbacks in life do not develop depression. So why do the others?

One reason may lie in the serotonin transporter. A critical study conducted by Avshalom Caspi, Ph.D., of the Institute of Psychiatry in London, and colleagues, and published in the July 2003 Science, showed that persons with one or two copies of the S variant of the serotonin transporter gene were more likely, in the throes of stress, to get depressed or to kill themselves than persons with two copies of the L variant of the gene were. The finding has since been replicated by several investigators.

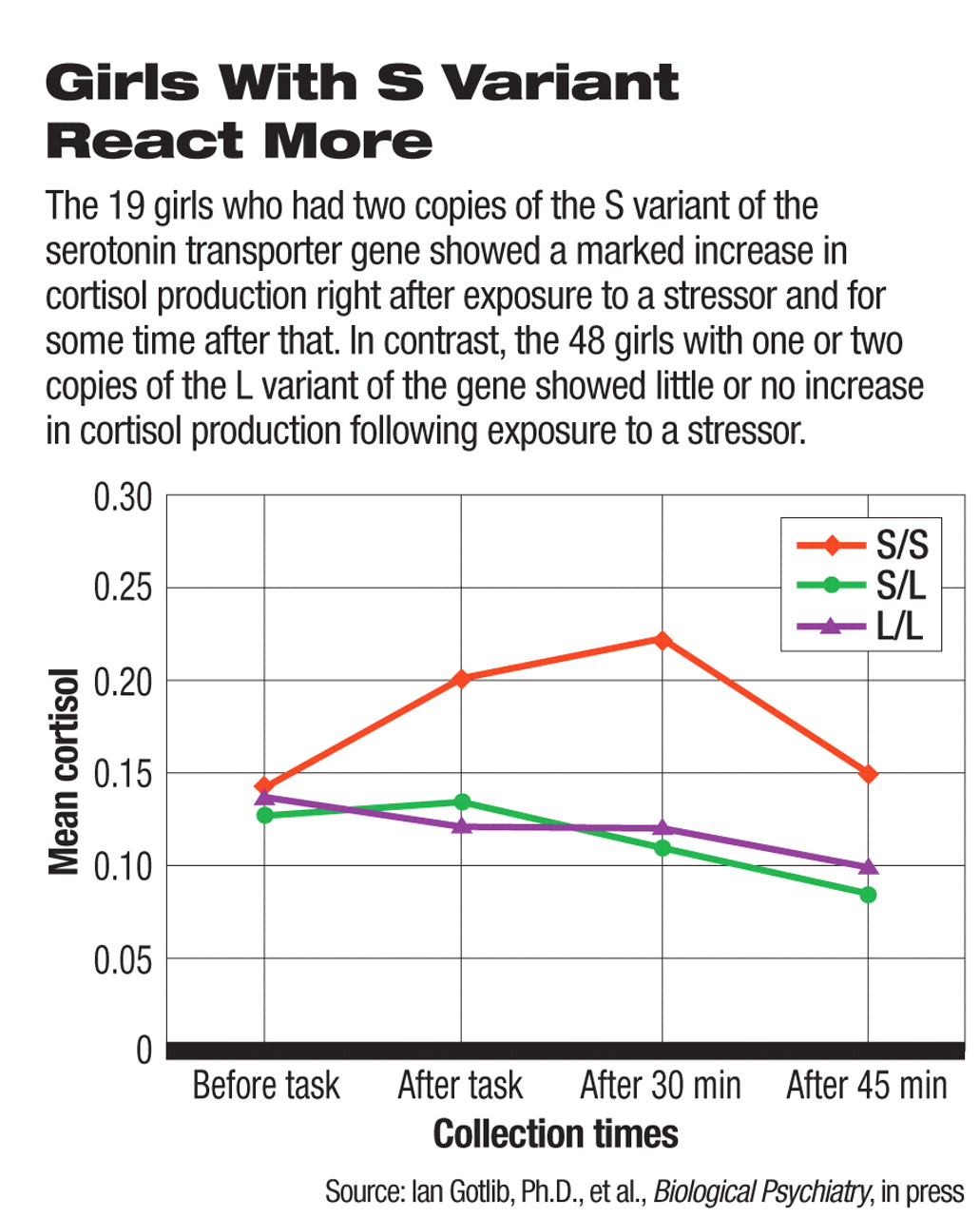

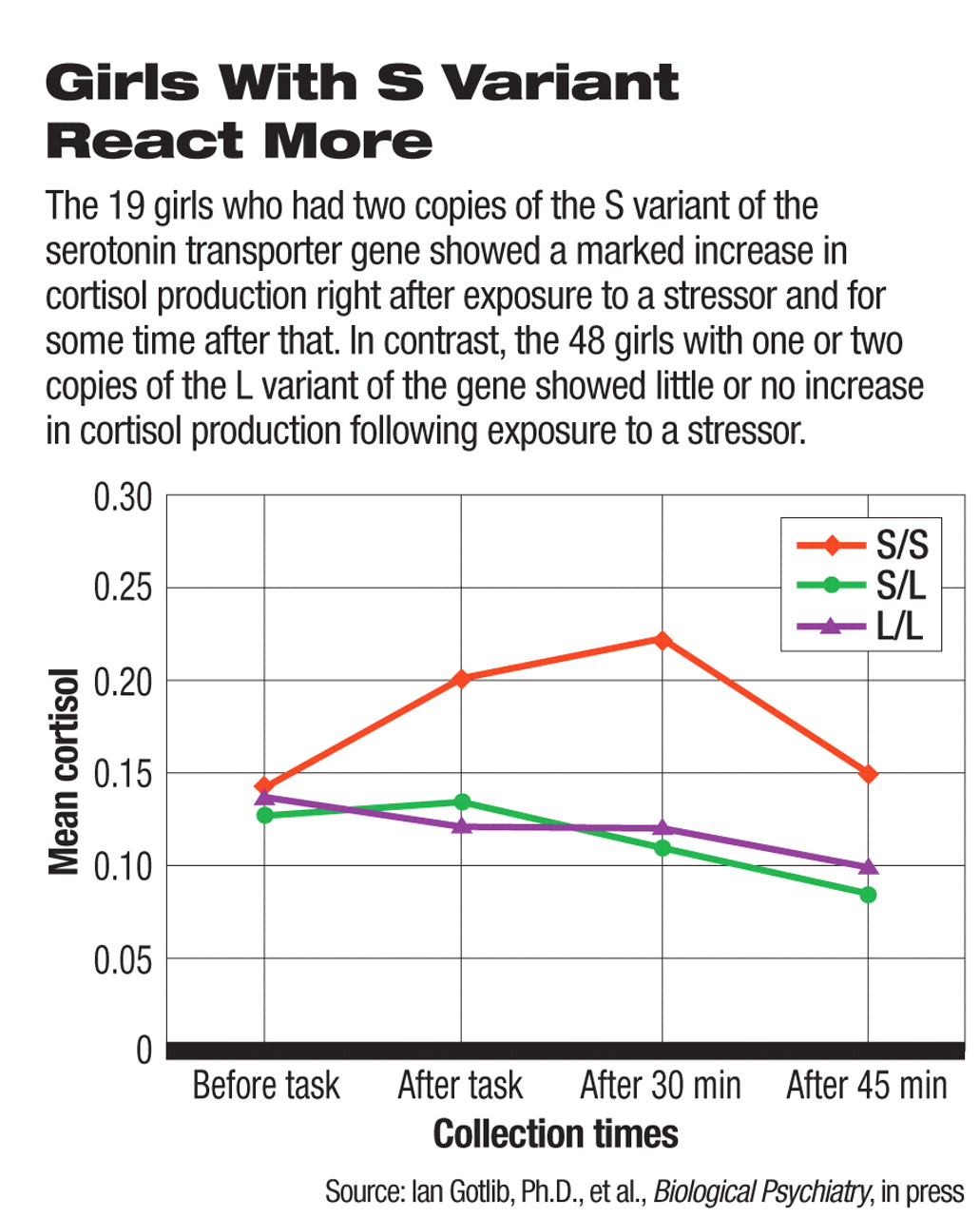

But how does the S variant of the gene contribute to depression in the wake of stress? Ian Gotlib, Ph.D., a professor of psychology at Stanford University, and coworkers. suspected that the stress hormone cortisol might be the biological mediator and conducted a study to find out.

Sixty-seven girls without an Axis I disorder were genotyped for the S or L variant of the serotonin transporter gene, then exposed to a standard lab stress task. Cortisol levels in the girls' blood were measured before the stressor, after the stressor, and during an extended recovery period. The researchers then looked to see whether those girls with the S variant produced different levels of cortisol than girls with the L variant. Indeed, the girls who had two copies of the S variant showed a marked increase in cortisol production immediately following exposure to the stressor and for some time after that. In contrast, the girls with one or two copies of the L variant showed a slight increase in cortisol production immediately following exposure to the stressor but then a decrease after that.

Thus cortisol—or what Gotlib and his group call “biological stress reactivity”—might be the means by which the S gene variant heightens susceptibility to depression in the face of stress, they concluded in their study report, which is in press with Biological Psychiatry.

Not the Only Player

But the S variant of the serotonin transporter gene does not seem to be the only player in the serotonin-transmitter system to produce depression in stressful conditions. The serotonin 2A receptor seems to be involved too, another new study—also in press with Biological Psychiatry—shows.

Actually the serotonin 2A receptor has been known to be implicated in depression. For example, several studies have found increased binding of 2A receptors in the frontal cortex of depressed suicide victims. Also, difficulty in coping with stress has been known to increase the risk of a major depression. So Vibe Frokjaer, M.D., of the Center for Integrated Molecular Brain Imaging and Neurobiology Research at Copenhagen University Hospital in Denmark, and colleagues wanted to find out whether there is any connection between difficulty in coping with stress and 2A receptor-binding in the frontal cortex.

Eighty-three volunteers without a history of psychiatric illnesses completed the Revised NEO Personality Inventory, a standardized personality questionnaire. The binding of serotonin 2A receptors in their brains was measured with positron emission tomography (PET). The researchers found that subjects who scored high on neuroticism—that is, on difficulty in coping with stress—had significantly more 2A receptor-binding in the frontal cortex than did the subjects who scored low on neuroticism.

'Interesting' Question Raised

Thus, the serotonin 2A receptor, like the serotonin transporter, seems to be involved in the unleashing of depression in the face of stress. But are the serotonin 2A receptor and the serotonin transporter complicit as they carry out this task?

“That's an interesting question,” Gotlib said. “It's possible that we'll ultimately find an interaction, but at this point they do not seem to operate in the same way.”

“That is a hard one; I wish I knew,” Frokjaer said. In fact, he and his colleagues will be examining the binding of both serotonin 2A receptors of serotonin transporters in the same subjects to see whether they might interact in some way in transforming stress into depression.

Meanwhile, the results obtained by Gotlib and his team and by Frokjaer and his may have some clinical implications. For instance, persons genetically vulnerable to stress-induced depression—say, with two S copies of the serotonin transporter gene—might be offered training in stress management, Gotlib proposed.

The study by Gotlib and his group was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and the National Alliance for Research in Schizophrenia and Affective Disorders.

The study by Frokjaer and his team was financed by the Danish Medical Research Council; the University of Copenhagen; the 1991 Pharmacy Foundation; the Lundbeck Foundation; the EU Fifth Framework Program; the Juhls Foundation; Laegernes Forsikringsforening af 1891, and Fonden af 1870.

Abstracts of “HPA Axis Reactivity: A Mechanism Underlying the Associations Among 5-HTTLPR, Stress, and Depression” and“ Frontolimbic Serotonin 2A Receptor Binding in Healthy Subjects Is Associated with Personality Risk Factors for Affective Disorder” can be accessed at<www.journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/bps> by clicking on “Articles in Press.” ▪