While several medications have been approved for smoking cessation in adults, their effectiveness in adolescents has not been established. Bupropion extended-release tablets, marketed as Zyban for adult smoking cessation, appears to have benefits for younger smokers, but rapid relapse is a significant drawback, according to a new study in the November 2007 Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine.

A total of 312 adolescents aged 14 to 17 who smoked at least six cigarettes per day and had attempted to quit at least twice were recruited to participate. More than half (58 percent) were boys. They were randomly assigned, in equal ratio, to receive placebo, bupropion 150 mg/day, or bupropion 300 mg/day for one week before and six weeks after a designated quit date. These participants returned to the clinic once a week to receive a brief counseling session to encourage them to maintain the abstinence.

Efficacy was measured by self-reported abstinence using a questionnaire, and the reports were confirmed by two different biochemical methods: exhaled carbon monoxide level weekly and cotinine levels in urine at the week 2 and week 6 visits. After weekly visits for about eight weeks, the study staff conducted two more assessments three months and six months after the initial quit date to see how many participants stayed off cigarettes.

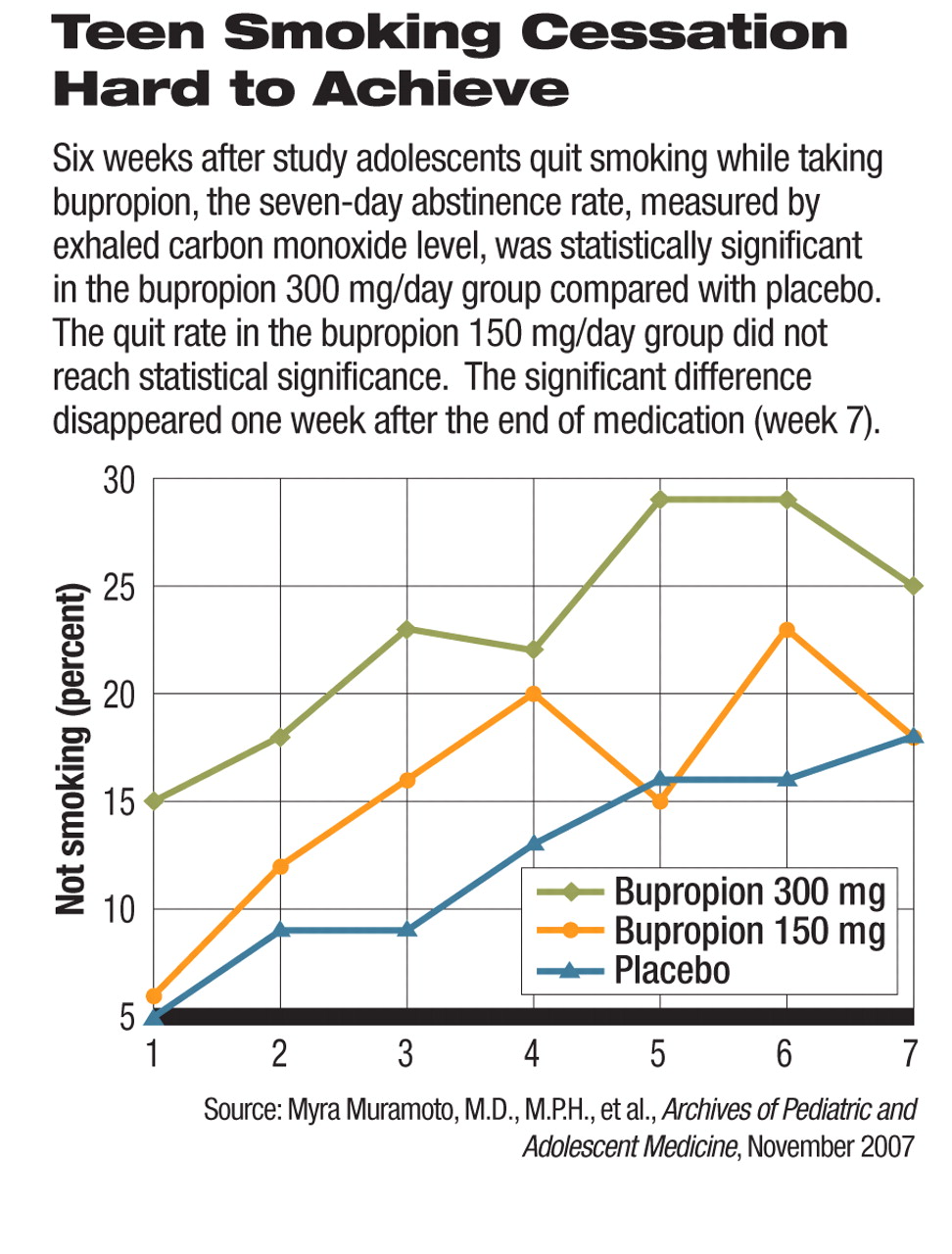

Six weeks after the initial quit date, the abstinence rates (defined as percentage of participants not smoking in the past seven days) as confirmed by cotinine were 5.6 percent, 10.7 percent, and 14.5 percent in the placebo, bupropion 150 mg/day, and 300 mg/day groups, respectively. Participants on bupropion 300 mg/day saw a modest but statistically significantly higher quit rate than placebo at weeks 1, 3, and 5 and 6 (see

graph).

The quit rate in the bupropion 150 mg/day group was not significantly different from that of the placebo group. As soon as the medication was stopped at the end of week 6, however, many participants relapsed, so that the quit rates at week 7 were no longer significantly different across all three groups.

“We found that there did seem to be an effect with medication treatment for smoking cessation, but it didn't last after the medication was stopped,” Myra Muramoto, M.D., M.P.H., the lead author of the study told Psychiatric News. Muramoto is an associate professor in the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine.

The study was funded by the National Cancer Institute, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and GlaxoSmithKline.

A previous study by Eric Moolchan, M.D., and colleagues reported a higher rate of smoking cessation after using nicotine patches and gums for 12 weeks, compared with placebo patches and gums, in a study in 13- to 17-year-old adolescents. “Combined with Dr. Moolchan's study findings, our results show that pharmacotherapy can be useful for younger smokers,” said Muramoto.

The researchers found notable discrepancies among self-report, exhaled carbon monoxide levels, and urinary cotinine levels. “Adolescents are known to be less reliable in reporting compliance,” said Muramoto.“ Cotinine is more accurate because of its longer half-life [compared with exhaled carbon monoxide], especially for low-level smokers.”

How to help young people stop smoking is a poorly understood and often overlooked area in medicine and public health. The modest effectiveness and high relapse rates in this study illustrate the difficulty in treating nicotine addiction in young people. “A message to clinicians is that, just because adolescents generally have a lower level of smoking [compared with adults], it doesn't mean they have an easier time quitting,” Muramoto said.

Early intervention, however, is important. Most adult long-term smokers acquired the habit in adolescence, and 23 percent of high school students are smokers, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data and a 1994 surgeon general's report. In a commentary published in the November 14, 2007 Journal of the American Medical Association, Suzanne Colby, Ph.D., and Chad Gwaltney Ph.D., concurred with the authors of this study that adolescent smoking cessation research is still in its infancy. They pointed out that smoking cessation efforts in adolescents pose unique challenges and should not be handled in the same way as smoking research and treatment in adults.

“Pharmacotherapies designed and approved for adults simply may not work as well for adolescents...[and] the mechanisms underlying smoking may not be the same for adolescents and adults,” they wrote. “Even basic questions about the severity and time course of nicotine withdrawal are not well understood.”

“A physician can't just write a prescription and tell a patient to quit smoking. Behavioral support is critical for smoking cessation and has been used for a long time before any pharmacologic treatment became available,” Muramoto emphasized. In this study, brief counseling was provided weekly along with assessments during the study and had some effects on abstinence even in the placebo group. She recommended psychosocial interventions as an important part of smoking cessation treatment for adults as well as youths. “Coaching really works,” she said.