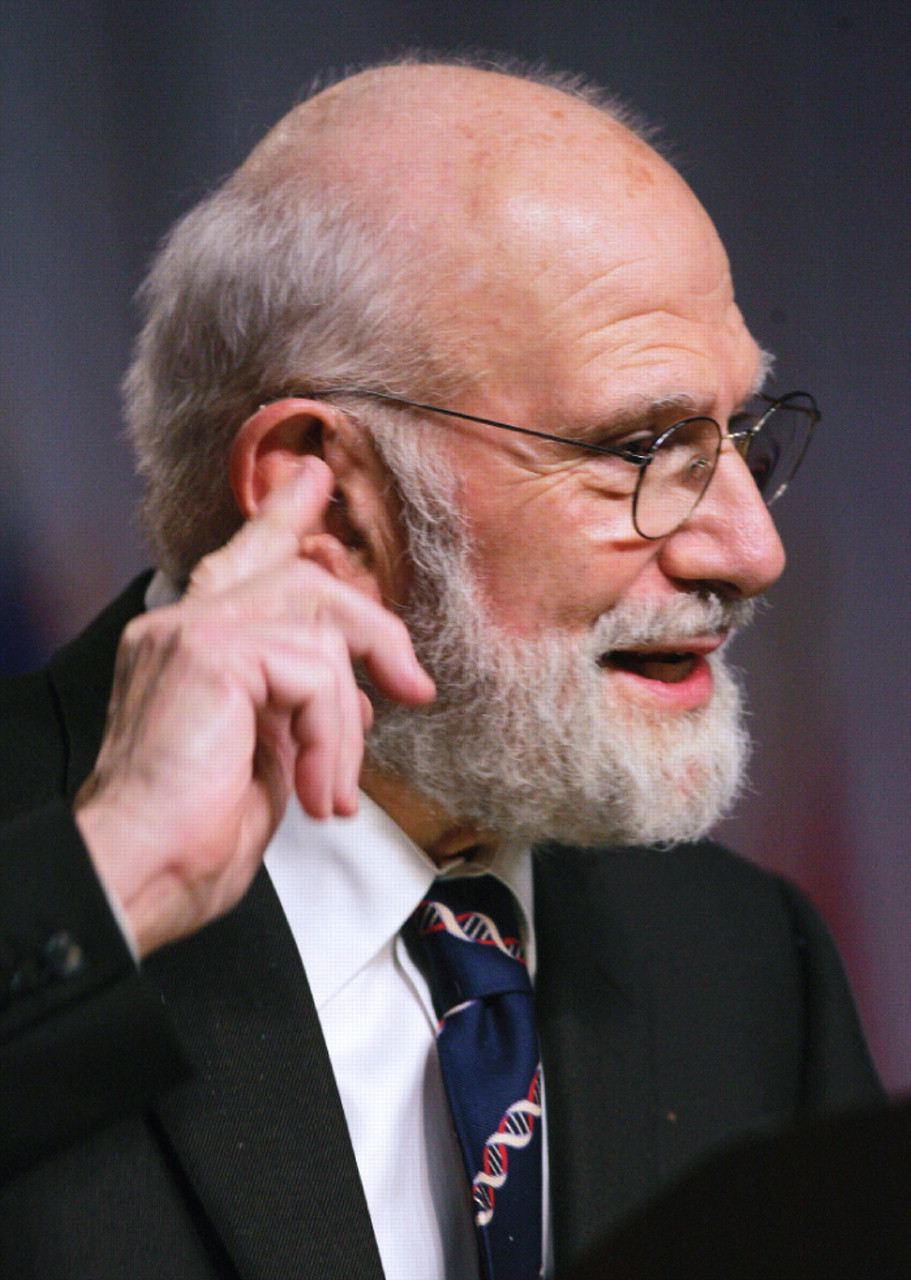

Music and the mind was the subject of an address by neurologist and famed author Oliver Sacks at the Convocation of Fellows at APA's 2008 annual meeting in Washington, D.C., last month.

Using the stories of curious and uncanny psychological phenomena for which he has become known, the author of the 2007 book Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain told psychiatrists and their guests that music is heard in regions of the brain that regulate both motor movements and emotion.

For that reason, music is uniquely capable of influencing behavior. He noted, for instance, that during the processional when he and APA fellows filed into the convocation hall earlier that evening, he felt himself beginning to walk in time to the music.

“Music is at once sensory, emotional, aesthetic, and motor,” Sacks said. He said he believes music can be usefully incorporated into therapy for neurological and psychiatric conditions, including the most severe disorders.

“Most of us also experience music in the mind, musical imagery which tends to be involuntary,” Sacks said. This is a feature of the brain that he said “alleviates boredom and fatigue and buoys the spirit.”

And music is also heard in dreams. “So one could say that music never sleeps,” he said. In fact, he suggested that psychiatrists ask their patients not only about their dreams but also about the music they hear in their minds. Like dreams, such music can reveal meaningful material.

He also described stories gathered from his own clinical practice, and from stories and anecdotes sent to him by readers, of individuals who experienced musical hallucinations—who believed they heard music when none was playing. For instance, he described a man who became fixated on the song“ Love and Marriage,” made famous initially by Frank Sinatra and later as the theme song of the popular television series “Married... With Children.”

“He got trapped inside the tempo of the song,” Sacks said.“ After incessant repetition, the song lost all its charm and musicality and began to interfere with his schoolwork.”

Another woman he described was visiting her sister over a holiday when she began to hear the melody of “Amazing Grace” so convincingly that she believed that it must have been playing in a nearby church. Later, the woman wrote to Sacks about the experience, telling him, “I looked down and realized the music couldn't possibly be coming from anywhere but inside my head.”

She sent Sacks a “playlist” that included the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” Beethoven's “Ode to Joy,” the drinking song from “La Traviata,” and “A Tisket, a Tasket.”

“And one night,” he quoted the woman as telling him, “I heard a splendidly solemn version of 'Old MacDonald Had a Farm'—followed by thunderous applause.”

“She was perfectly sane,” Sacks said. “Many people experience musical hallucinations, and I am sure it is underreported. About 80 percent have severe deafness. Among older people particularly, [deafness] conduces to musical hallucinations.

“It is as if the auditory cortex isn't getting its crucial nourishment,” Sacks said. “So it delves down into memory and regurgitates music from childhood or earlier in life, in the same way that people with visual impairments can have visual hallucinations.

“People are afraid to mention these for fear of being perceived as crazy. One subject talked about his intracranial jukebox.”

According to Sacks's official Web site at<www.oliversacks.com>, the British-born physician and author began working as a consulting neurologist for Beth Abraham Hospital in the Bronx, a chronic-care hospital where he encountered patients who had spent decades in strange, frozen states, like human statues, unable to move.

Sacks recognized these patients as survivors of the great pandemic of sleeping sickness that had swept the world from 1916 to 1927. He treated them with a then-experimental drug, levodopa, which enabled them to come back to life. They became the subjects of his book Awakenings, which later inspired a play by Harold Pinter (“A Kind of Alaska”) and the Oscar-nominated feature film (“Awakenings”) with Robin Williams and Robert De Niro.

He has since become known for his collections of case histories describing rare and remarkable neurological experiences and phenomena. In The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and An Anthropologist on Mars, he describes patients struggling to live with conditions such as Tourette's syndrome, autism, parkinsonism, musical hallucinations, epilepsy, phantom limb syndrome, schizophrenia, retardation, and Alzheimer's disease.

In July 2007 he was appointed a professor of clinical neurology and clinical psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center, and he was designated Columbia University's first Columbia Artist. ▪