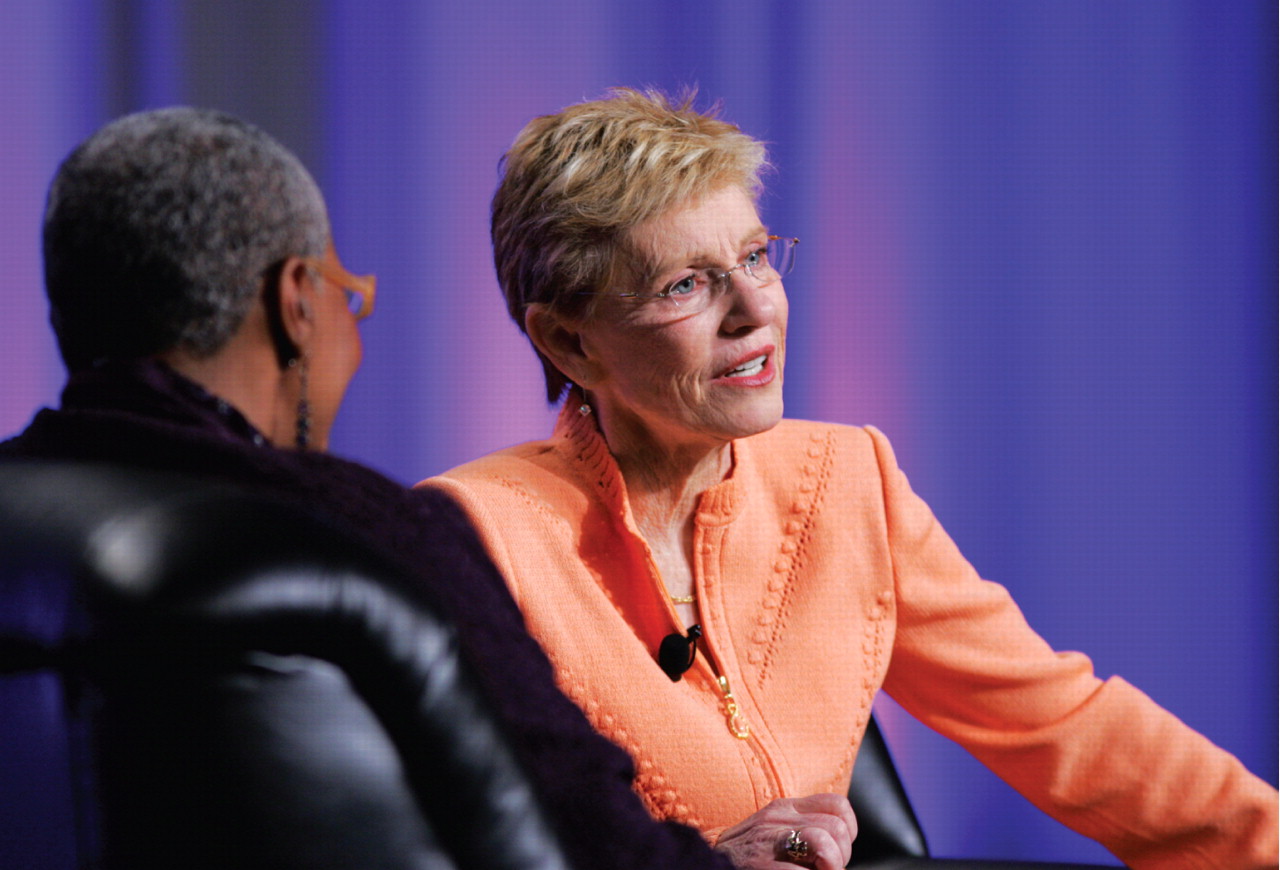

After spending decades in the spotlight as a star of television and movies, actress Patty Duke proclaimed to a large crowd at APA's 2008 annual meeting last month that mental health advocacy is her “true calling.”

After struggling for nearly 20 years with what she described as mania-induced psychosis, violent rages, devastating depressions, and suicide attempts, Duke found lasting solace through psychiatric treatment. When she was finally diagnosed at the age of 35 with what was then known as manic-depressive illness, she said that she experienced tremendous relief.

“I thought, 'Thank God. It has a name,' ” the actress declared at the 2008 Conversations event, which is held each year during the annual meeting and is sponsored by the American Psychiatric Foundation with funding from AstraZeneca. Duke began taking lithium the day after she was diagnosed, she said, which, together with psychotherapy, brought a calm she had long been without.

Duke was born in 1946 to what she described as loving but dysfunctional parents—her father was an alcoholic, and her mother battled depression. To escape the family strife, her older brother, Raymond, became involved in the drama department of the local boys club and was eventually discovered by John and Ethel Ross, who were managers of child actors.

They soon saw untapped potential in young Anna, and her mother turned her over to the Rosses so that they could tutor her and teach her the skills of the trade. Her new name, they declared, would be Patty.

Her career vaulted skyward. She earned great recognition for her portrayal of Helen Keller in the Broadway play “The Miracle Worker” and at age 16 earned the Academy Award for best supporting actress for the same role in the film version. In 1979 she won an Emmy Award for playing Keller's teacher, Annie Sullivan, in a television version of “The Miracle Worker.”

She also earned an Emmy nomination for her work on “The Patty Duke Show,” which aired for three years beginning in 1962.

When Duke was a teenager, she began to experience mood swings that for a good portion of the next 20 years included paralyzing depressions, on-set tantrums, and multiple suicide attempts. Her manias brought insomnia, psychosis, and irrational decisions that led her, for example, to marry a complete stranger on a whim. “I was on a manic high” when that happened. “I don't know what his story was,” she said, stirring laughter in the audience.

Her second husband, actor John Astin, encouraged Duke to seek help for her devastating depressions when she was in her mid-30s. Her psychiatrist diagnosed her with manic-depressive illness after seeing her in the throes of mania during an emergency visit.

After beginning lithium therapy, Duke experienced a calm that had eluded her up to that point and was able to function more efficiently, she noted.

In an interview with Psychiatric News, Duke said that her performance in the role of Neely O'Hara in the 1967 film “Valley of the Dolls” was in part driven by her undiagnosed illness. “I was still acting out at the time” that the movie was being filmed, she recalled.

The role that has brought her inspiration for almost 50 years, however, is that of Helen Keller in “The Miracle Worker.” “Annie Sullivan and Helen Keller were role models for me,” she stated.

One of the highlights of her life was meeting Keller at age 80 at Keller's house in Tuscumbia, Ala., when Duke was just 12. “She was a ball, just really funny,” Duke recalled.

Duke first disclosed information about her mental illness in a TV Guide interview, she said, after which publishers began to approach her about writing an autobiography. That book, Call Me Anna, was published in 1988.

Duke began traveling around the country to speak about her experiences with mental illness and recovery and soon found her niche as a mental health advocate.

With the help of her husband, Mike Pearce, and her nephew, Duke established the Online Center for Mental Illness several years ago as a resource for people struggling with mental health problems. The site includes a blog by Duke, a message board, and resources for people with mental illness.

“Acting was a means to advocacy for me,” she said. “This is where my heart is.” ▪