The search for biochemical markers indicating resilience or vulnerability to stress-related disorders continues but has not yet reached the stage where such markers can be used with assurance for diagnosis, according to researchers in the field.

Neuropeptide Y, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and cortisol are some of the current leaders in this race, with dark-horse peptide p11 moving up on the outside (Psychiatric News, October 2).

The HPA axis has held a central focus of attention in this search, given its role in response to stress. Cortisol has been studied for decades. The conventional view has held that in people with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), basal cortisol is lower but is hypersuppressed with a low dose of dexamethasone in the dexamethasone suppression test, while generally people with major depressive disorder have higher basal cortisol levels and show nonsuppression on the same test. Patients with psychotic depression show even higher rates of nonsuppression, said Carlos Zarate, M.D., chief of experimental therapeutics in the Mood and Anxiety Disorders Program at the National Institute of Mental Health, in an interview.

A systematic review of 37 studies of cortisol in people with PTSD published from 1980 to 2005 found that there was no overall difference in basal cortisol levels between patients and controls. However, subgroup analyses of the same literature indicated some significant associations, depending on the population studied and the type of measurement used, wrote Marie-Louise Meewisse, M.Sc., in a November 2007 review in the British Journal of Psychiatry. Meewisse is with the Center for Psychological Trauma in the Department of Psychiatry and Academic Medical Center de Meren at the University of Amsterdam.

Studies that measured plasma or serum cortisol—as opposed to urinary or salivary—found lower levels in people with PTSD than in controls with no trauma exposure. However, no differences were recorded when comparing PTSD patients with trauma-exposed controls who did not have PTSD. Also, studies of those with PTSD covering only females or victims of physical or sexual abuse and those sampling cortisol in the afternoon recorded lower levels than controls, according to Meewisse.

“This study shows that cortisol levels do not relate to PTSD in general, but rather seem to mirror trauma exposure and PTSD subgroups,” she wrote.

Elusive Protein Cited

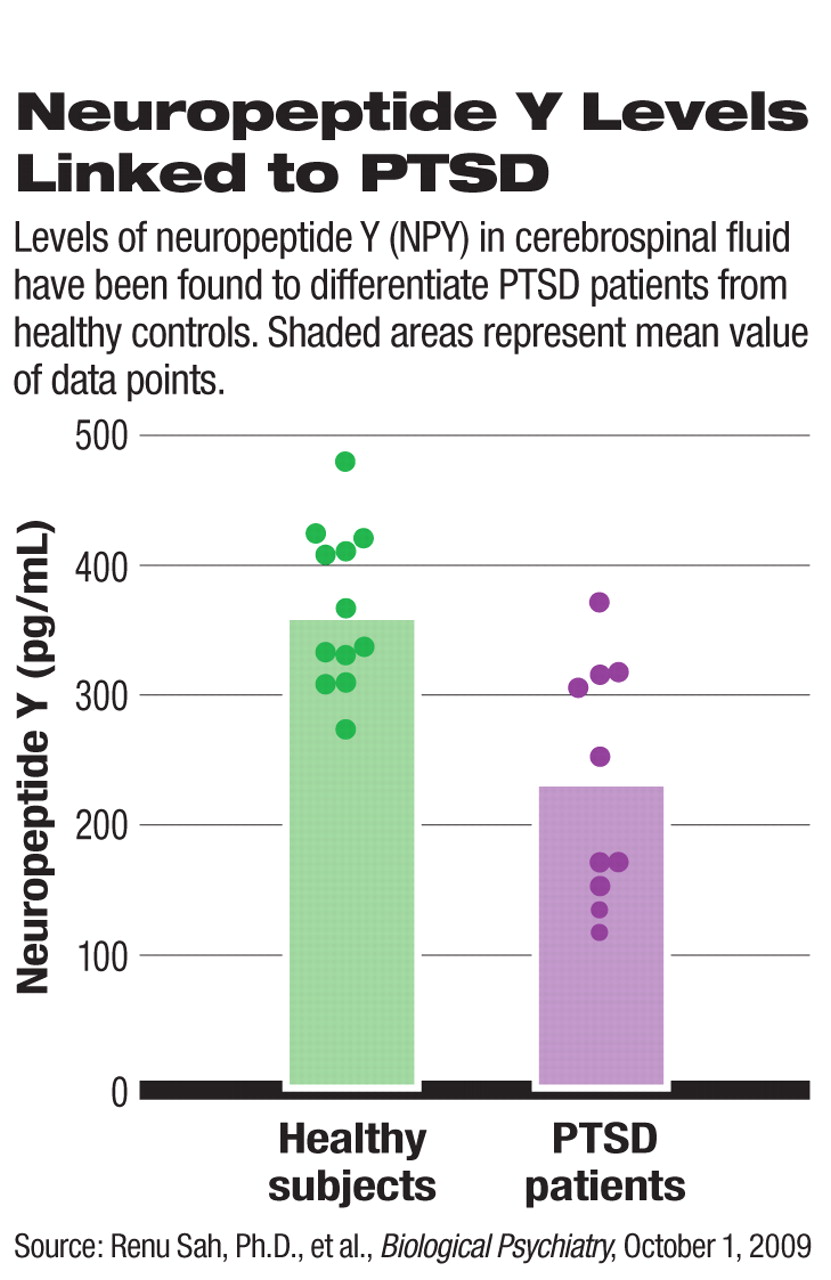

Neuropeptide Y (NPY) regulates stress and anxiety and is widely distributed in the brain, said Zarate. Plasma levels of NPY rise when people are under severe stress but are low among patients with PTSD.

A small study of NPY levels in cerebrospinal fluid found that they are lower in combat veterans with PTSD compared with healthy controls, even after adjusting for body mass index and age.

NPY may be a “pathophysiological feature of the disorder... and a possible therapeutic target in PTSD,” wrote Renu Sah, Ph.D., a research assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine, and colleagues in the October 1 Biological Psychiatry. The authors cautioned that the difference in effects observed may be due to trauma exposure and not PTSD, since the control subjects had not been exposed to trauma. Their work needs to be replicated and expanded to include a larger number of subjects, with different control groups, including trauma-exposed people without PTSD, they said.

Such work on NPY appears typical, said Zarate. “There are many small studies, they are hard to interpret, and few have been replicated.”

In fact, almost every approach to characterizing PTSD runs into numerous questions that must be answered before one can draw conclusions, said Zarate: Does sexual abuse produce the same trauma as a natural disaster? Is civilian trauma the same as combat? Are the effects of a single event the same as continuing trauma? What are the effects of ethnicity, culture, or nationality?

Real Stress Test

Yet another biomarker candidate is the endogenous hormone DHEA and its metabolite dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate, according to a paper in the August 15 Biological Psychiatry. Either or both of the DHEAs are decreased in a number of psychiatric disorders, including depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and PTSD.

To test the relationship of DHEA to stress, Charles Morgan III, M.D., and colleagues studied U.S. military personnel taking the Special Forces Underwater Warfare Operations Diver Qualification Course. For the final test in the course, participants were dropped in the ocean at night and had to make their way underwater to a target on shore, without surfacing, with a limited supply of oxygen, and with the knowledge that their careers were on the line.

“Pretty profound alarm reactions are involved, when the body is telling you that there's not enough oxygen or too much carbon dioxide,” said Morgan in an interview.

Course participants depended on visuo-spatial memory functions mediated by the hippocampus and planning and self-monitoring mediated by the prefrontal cortex. Higher DHEA levels are believed to buffer the effects of chronic stress, and indeed, Morgan found that soldiers with higher baseline levels of DHEA performed better on the test. Also, those with higher levels of stress-induced DHEA had fewer symptoms of dissociation.

“Dissociation is a negative predictor,” said Morgan. “You must be acutely aware of where you're going, and mentally pulling out is a bad thing.”

Morgan doesn't yet know if the candidates with high DHEA levels were born that way or have developed that capacity by experience and training. He suggests that a future trial might also see if taking DHEA (available over the counter as an “anti-aging” dietary supplement) might improve the scores of those who have lower natural levels of the hormone.

Someday biomarkers may help predict vulnerability or resilience to illness, or provide diagnoses and the surrogate clinical endpoints to track response to treatment. However, there may not be a single winner in the biomarker sweepstakes, said Zarate.

“There is no one chemical test on the horizon,” he said.“ It will probably take some combination of biomarkers and neuroimaging to characterize mental illnesses.”

An abstract of “Low Cerebrospinal Fluid Neuropeptide Y Concentrations in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder” is posted at<www.journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/bps/article/S0006-3223(09)00637-4/abstract>. An abstract of “Relationships Among Plasma Dehydroepiandrosterone and Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate, Cortisol, Symptoms of Dissociation, and Objective Performance in Humans Exposed to Underwater Navigation Stress” is posted at<www.journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/bps/article/S0006-3223(09)00446-6/abstract>.▪