Adrian Raine, D.Phil., chair of criminology at the University of Pennsylvania, has a passion. It is peering into the brains of antisocial people to see whether their brains differ from those of people who are not antisocial.

He is finding that such a difference does in fact exist.

For instance, in 2000, he and his coworkers reported that the prefrontal cortex was significantly smaller in violent, antisocial men than in controls (Psychiatric News, March 3, 2000). In 2005, he and his colleagues reported that pathological liars had more white matter in the prefrontal cortex than normal control subjects (Psychiatric News, November 18, 2005). And now he and his colleagues reported, in the September Archives of General Psychiatry, that the amygdalae of psychopathic individuals are significantly smaller than those of nonpsychopathic individuals.

The amygdala regions of the brain are known to process emotions and especially to play a role in fear. So Raine and his colleagues suspected that the amygdalae of psychopaths might differ from those of nonpsychopaths, and they launched a study to test the hypothesis.

Individuals who sought work through temporary employment agencies were recruited for the initial phase of the study. They were screened with the Hare Psychopathy Checklist-Revised. The instrument assesses people for factors such as superficial charm, cunning and manipulation, pathological lying, impulsivity, irresponsibility, callousness, lack of remorse, and other psychopathic traits. A score of 23 or higher is used to define psychopathy.

The researchers found 27 individuals who had a score of 23 or higher on the checklist and enrolled them in the second phase of their study. They then found 32 individuals who scored very low on the checklist (scores of 5 to 14) and who matched the 27 psychopathic subjects on age, gender, and ethnicity. These 32 individuals were enrolled as controls in the second phase of the study.

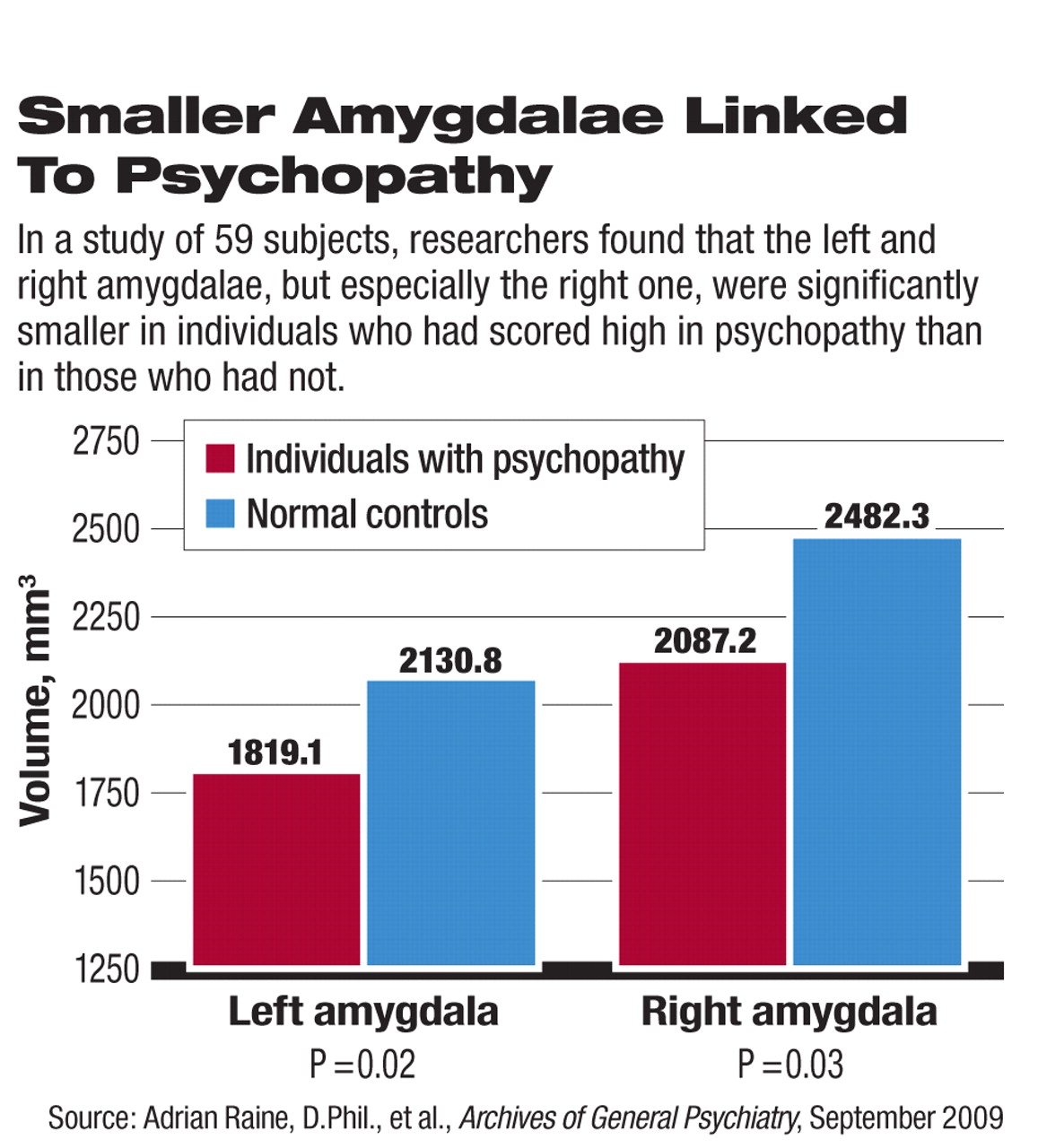

During the second phase, the left amygdala and the right amygdala of each of the 59 subjects were measured with structural magnetic resonance imaging. Both the left and right amygdalae in the psychopathic group were found to be significantly smaller than those in the control group. These results held firm even when two possibly confounding factors—socioeconomic status and substance/alcohol dependence—were considered.

Thus, “amygdala structural abnormalities are a key element in the neurobiological bases of psychopathy,” the researchers concluded.

The researchers suggested that the possession of amygdala abnormalities might “contribute to [the] emotional and behavioral symptoms of psychopathy.” One reason why they believe this might be the case is that rats and monkeys with amygdala damage have been found to display a lack of fear, as psychopathic individuals are likely to do. Another reason may be that some patients who have experienced amygdala damage as a result of disease have been found to have difficulty responding to facial expressions. Psychopathic individuals may have the same problem.

It's possible, of course, that the opposite is the case—psychopathy leads to abnormalities in amygdala volume—or that some other factors lead to both psychopathy and amygdala abnormalities.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.