Out of the million or so Americans who have Parkinson's disease, about a half also suffer from depression. Yet depression in Parkinson's disease is often underrecognized, underappreciated, and undertreated. Commonly the attitude is “Of course you are depressed; you have a serious illness.”

Moreover, there is not much scientific evidence demonstrating that parkinsonian depression can be successfully treated pharmacologically, and if so, by which antidepressant.

So Matthew Menza, M.D., a professor and interim chair of psychiatry at the Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, and his colleagues undertook a trial to answer this question. Although the trial included only 52 subjects, it appears to be the largest placebo-controlled trial to date exploring this question.

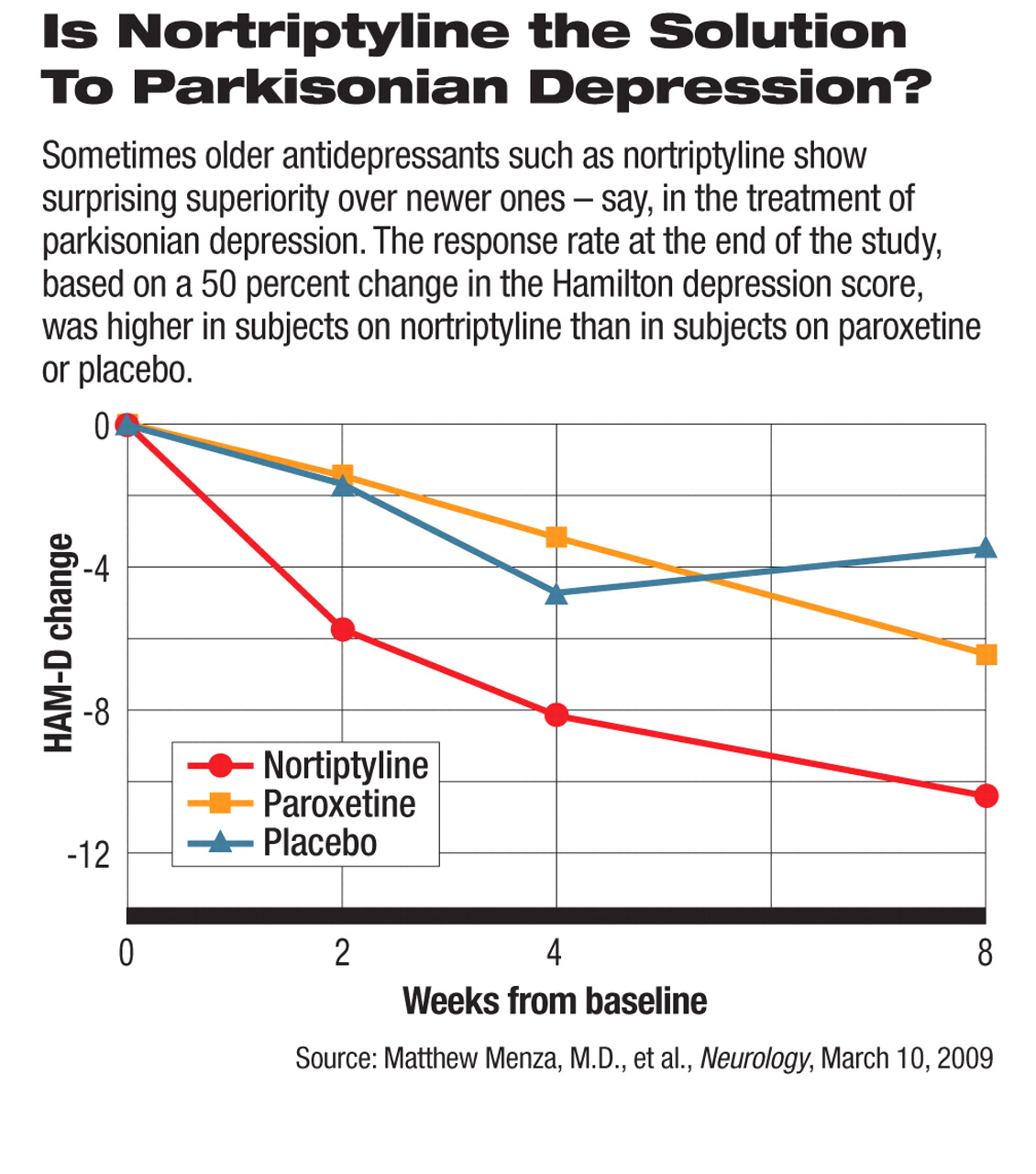

Subjects were randomized to receive for eight weeks an SSRI antidepressant (paroxetine), a dual reuptake inhibitor (nortriptyline), or a placebo. They were evaluated for depression at the start of the trial, during the trial, and at the end of the trial with the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. Menza and his colleagues compared the outcomes for the three groups. The response rate at the end of the study, based on a 50 percent change in the Hamilton depression score, was 53 percent for subjects on nortriptyline, 24 percent for subjects on a placebo, and 11 percent for subjects on paroxetine.

This finding, Menza told Psychiatric News, demonstrates, first of all, that Parkinson's patients do respond to antidepressants and, second, that the dual reuptake inhibitor nortriptyline is superior to the SSRI paroxetine for treating parkinsonian depression. “This is not to say that the SSRIs won't work in some patients,” he said, “just that percentage-wise, you may be better off started with a dual-action drug.”

The study also revealed that nortriptyline was superior to a placebo on secondary outcomes such as anxiety, sleep, and social functioning, whereas paroxetine was not. This finding is important because such symptoms are common in Parkinson's patients and cause considerable distress, Menza noted.

Furthermore, nortriptyline, like paroxetine, was well tolerated by subjects and had no adverse effects on subjects' hearts, even though it has been associated with cardiac arrhythmias.

Thus, this study appears to suggest that nortriptyline is superior to paroxetine in treating depression, anxiety, and sleep problems in Parkinson's patients and to be quite safe for such patients, Menza and his team concluded in their study report, which was published in the March 10 Neurology.

The challenge now, they pointed out in their report, is to find out whether the newer dual reuptake inhibitors venlafaxine and duloxetine are as effective as nortriptyline, or perhaps even more so, for such indications, and how their safety profiles compare with that of nortriptyline in Parkinson's patients. Neither venlafaxine nor duloxetine has been linked with cardiac arrhythmias. Two different groups of researchers—one in Rochester, N.Y., and the other in Italy—are undertaking trials to answer these questions, Menza told Psychiatric News.

Also to be answered is why nortriptyline seems to be superior to paroxetine in countering parkinsonian depression, Menza and his colleagues stated in their report. A recent study showed that Parkinson's subjects with depression had a deficiency in neurons that use norepinephrine in the limbic area of their brains. So one possible explanation for why nortriptyline counters parkinsonian depression better than paroxetine, they speculated, is because nortriptyline, being a dual reuptake inhibitor, replenishes not only serotonin, but norepinephrine in the limbic area of the brain, whereas paroxetine, being an SSRI, only replenishes serotonin.

This trial was funded by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. GlaxoSmithKline provided the paroxetine and placebo.

An abstract of “A Controlled Trial of Antidepressants in Patients With Parkinson's Disease and Depression” is posted at<www.neurology.org/cgi/content/abstract/72/10/886>.▪