Psychiatrists looking for work might consider Rhode Island.

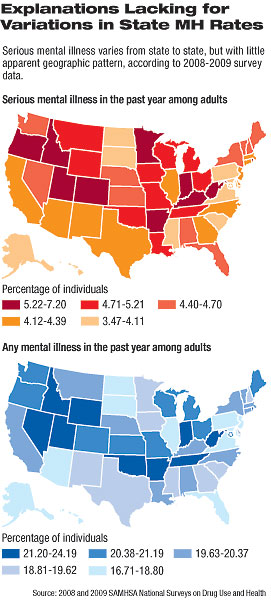

State-level results from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) show that the Ocean State, with 7.2 percent of respondents reporting a serious mental illness and 24.2 percent reporting any mental illness, led all states in both categories.

Previously, the NSDUH provided only national data, but this report, issued in October by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), provides for the first time state-level estimates of mental health indicators, said the agency.

SAMHSA defines "any mental illness" among adults aged 18 or older as the presence of any mental, behavioral, or emotional disorder in the past year that met DSM-IV criteria. Among adults with a disorder, those whose disorder substantially interfered with or limited one or more major life activities are defined as having serious mental illness.

The estimates were derived from data collected in 2008 and 2009 as part of the survey prepared by SAMHSA and by RTI International of Research Triangle Park, N.C.

Nationally, the rate of serious mental illness was 4.6 percent, and the rate of any mental illness was 19.7 percent.

Overall, more than 10 million American adults had a serious mental illness, and 44.5 million experienced any mental illness in the year prior to the survey.

Arkansas, Idaho, Utah, and West Virginia also recorded high percentages in both categories. Hawaii and South Dakota were tied for the lowest rates of serious mental illness (3.5 percent). Maryland reported the lowest rate of any mental illness, 16.7 percent.

"States with high and low rates of [serious mental illness] and any mental illness are located in all regions of the United States," said the report. "Factors that potentially contribute to the variation are not well understood and need further study."

Perhaps that uncertainty will bring a little relief to the folks in Providence.

The role of place is becoming one of the strongest predictors of outcomes, more so than "person" or "time," said Linda Cottler, Ph.D., M.P.H., a professor and chair of epidemiology in the College of Public Health and Health Professions and the College of Medicine at the University of Florida.

Hypotheses for geographic variations abound, Cottler told Psychiatric News.

Perhaps people with serious mental illness move to where the services are, which leads to increasing availability of services based on need, she suggested. Methodological issues might also have an effect on results, as well.

"I would want to know if there are imputations for missing data, or if people in some parts of the country are more likely to acknowledge their symptoms, then there could be differences," said Cottler.

In fact, statistical imputation was used to replace values for substance use, demographic, and other variables, noted the report. "However, the mental health variables used in this report were not imputed."

Rhode Island's ranking may not be of much greater concern than that of any other state, said Brady Case, M.D., director of Health Services Research at the Bradley Hospital and an assistant professor of psychiatry and human behavior at the Alpert School of Medicine at Brown University in Rhode Island.

"It's difficult to make much of the findings," Case told Psychiatric News. "You have to remember that this is not a comprehensive epidemiological study, but is a quick snapshot, a fairly limited measure of mental illness."

For one thing, the SAMHSA data are raw estimates of prevalence.

"They did not factor in age, gender, race, employment status, and so on," said Case.

Also, confidence intervals were rather wide, and the numbers sampled within a given state did not provide sufficient power to give an accurate ranking, he said. That would have to await several more years of data.

Nor did the report provide insight into treatment rates, a more important measure for states than prevalence, said Case.

"The states can actually do something about treatment," he said.

There may be yet another, more positive factor, said one Rhode Island health official.

"We have done a great deal of work to reduce the stigma of mental illness in Rhode Island," said Craig Stenning, director of the state's Department of Behavioral Healthcare, Developmental Disabilities, and Hospitals. "And so we always rank high on these types of surveys since people are more open to admitting their illness."

"Rhode Island has had among the lowest suicide rates in the country for years, and at times the lowest for young people," said Case. "Mental illness and suicide are not the same thing, but it goes to show how these rankings can be difficult to interpret."