The prevalence of mental health disability increased over the last decade, but not across the board.

The increase was greatest among adults who also reported disability due to other chronic conditions and among those with significant psychological distress but who had no mental health care contacts in the prior year, said Ramin Mojtabai, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of mental health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and Johns Hopkins School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry online September 22 in the American Journal of Public Health.

Mojtabai used data from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) covering the years 1997 to 2009.

The NHIS is a continuous cross-sectional in-person household survey that tracks health status, activity limitations, access to care, and other variables. One adult in the household is interviewed about the family, and a randomly selected person over age 18 is interviewed in greater depth.

The NHIS is one of the longest running health interview surveys, making it a good choice for observing trends over time, said Lisa Colpe, Ph.D., M.P.H., chief of the Office of Clinical and Population Epidemiology Research in the Division of Services and Intervention Research at the National Institute of Mental Health. Colpe was not involved in Mojtabai's research.

"The NHIS's only disadvantage is that it doesn't go too deeply into any one topic," she said, in an interview. "Its purpose is to monitor the indicators of health."

Mojtabai looked specifically at interactive disability—shopping, leisure, and so on, but not cognition, memory, or concentration, she noted.

About 21 percent of the 312,364 adults aged 18 to 64 participating reported a disability. The percentage did not change significantly over years included in the study.

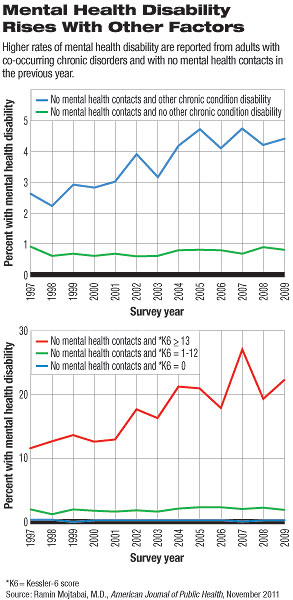

The percentage of participants reporting a mental health disability increased from 2.0 percent in 1997-1999 to 2.7 percent in 2007-2009, said Mojtabai.

That may not sound like much, but, he noted, "this change translates into an increase of approximately 2 million adults with mental health disability in this time period (from 3.2 million to approximately 5.2 million)."

Disability due to chronic conditions unrelated to mental health remained flat at about 20 percent over the time covered by the study. Psychological distress, measured on the Kessler-6 scale, rose from 2.9 percent to 3.2 percent, a statistically insignificant increase.

These other disability-related conditions included a wide range of physical problems involving vision or hearing, the musculoskeletal system, pulmonary function, cancer, diabetes, obesity, heart disease, and others.

"Mental health disability" as assessed in this study reflected depression, anxiety, or emotional problems.

The increase in mental health disability was largely related to people who did not have contacts with a mental health professional and who also met one of two other conditions: either a score of 13 or higher on the Kessler-6 scale of psychological distress or a co-occurring disability due to another chronic condition.

These outcomes are "intriguing and difficult to explain," said Mojtabai. He suggested that increasing public awareness of mental disabilities and greater recognition of mental health issues within the general medical community may be contributing to increased detection.

The confluence of mental and physical health may represent yet another opportunity to integrate the two more closely in general primary care settings, he noted.

Mojtabai's conclusion about greater meshing of primary and mental health care might already be reflected in his data, suggested Colpe, since primary care physicians are the source of mental health care for some of their patients.

"Just because [people with mental disabilities] are not seeing a defined mental health professional doesn't mean they are not getting mental health care," said Colpe. "They may be in care, but not by a specialist, especially in underserved areas."