Correlates of concomitant use of psychotropic medications

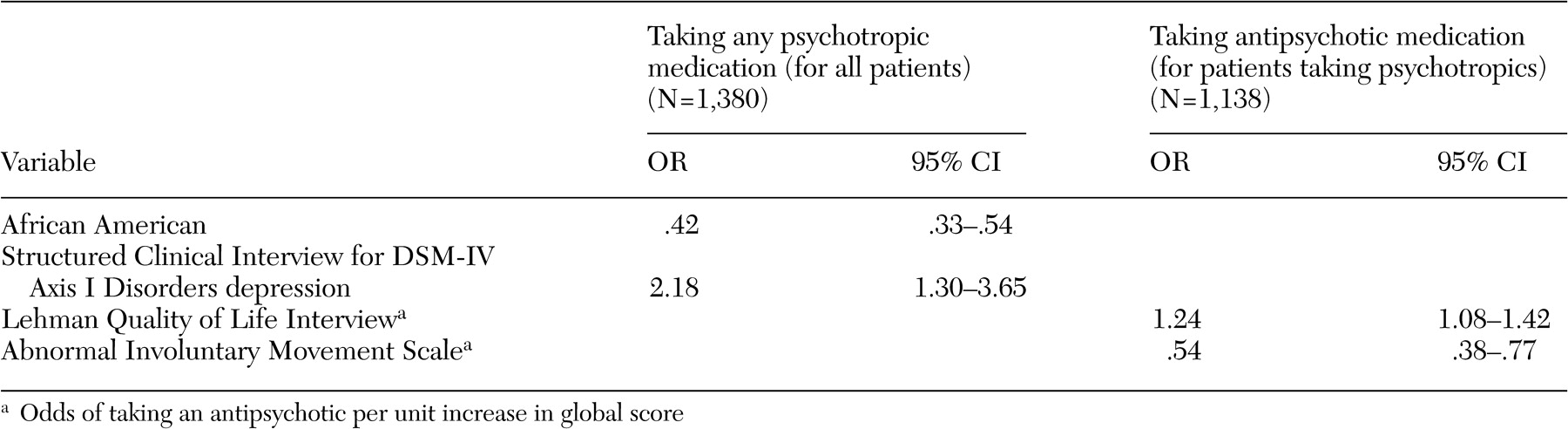

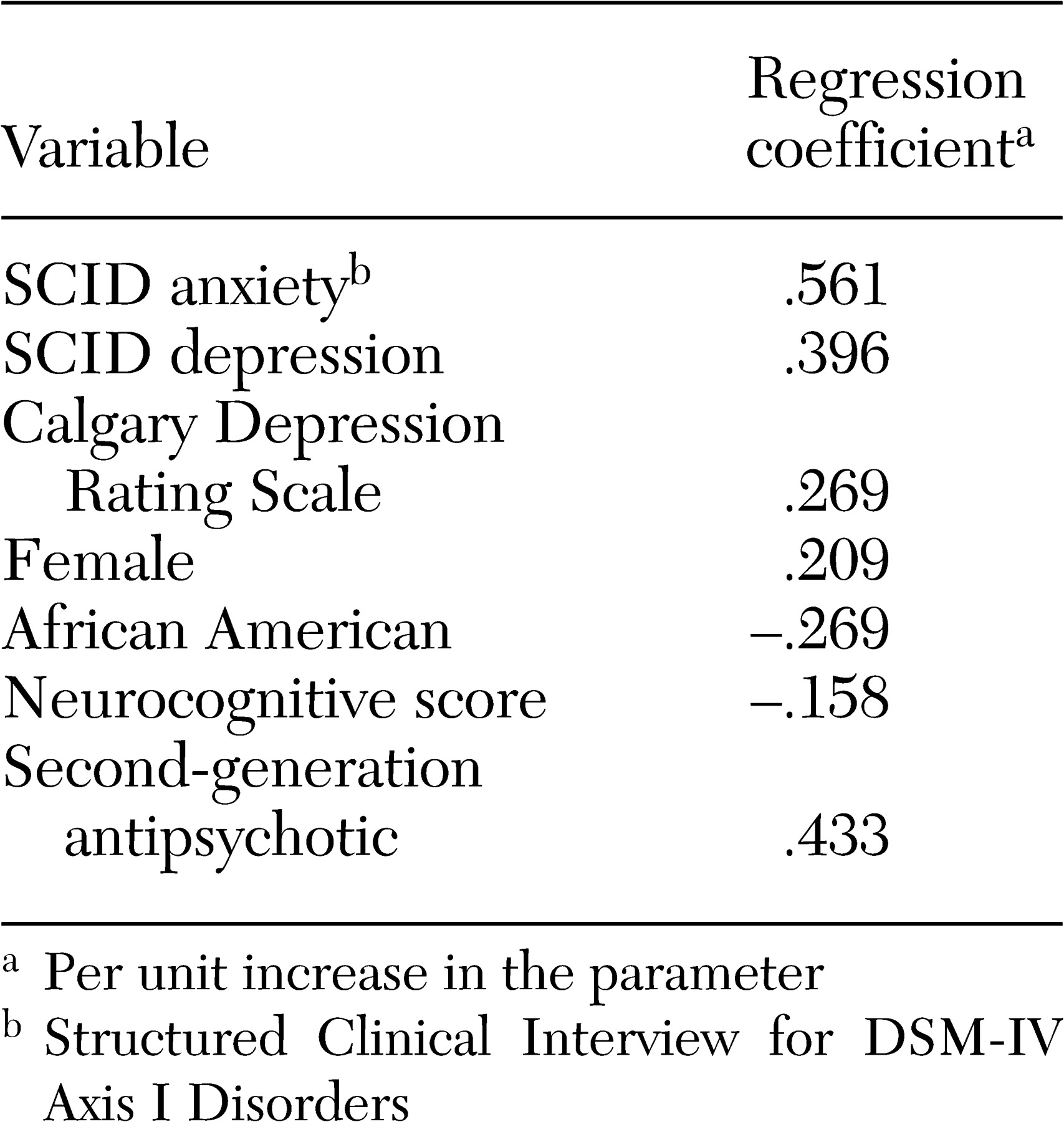

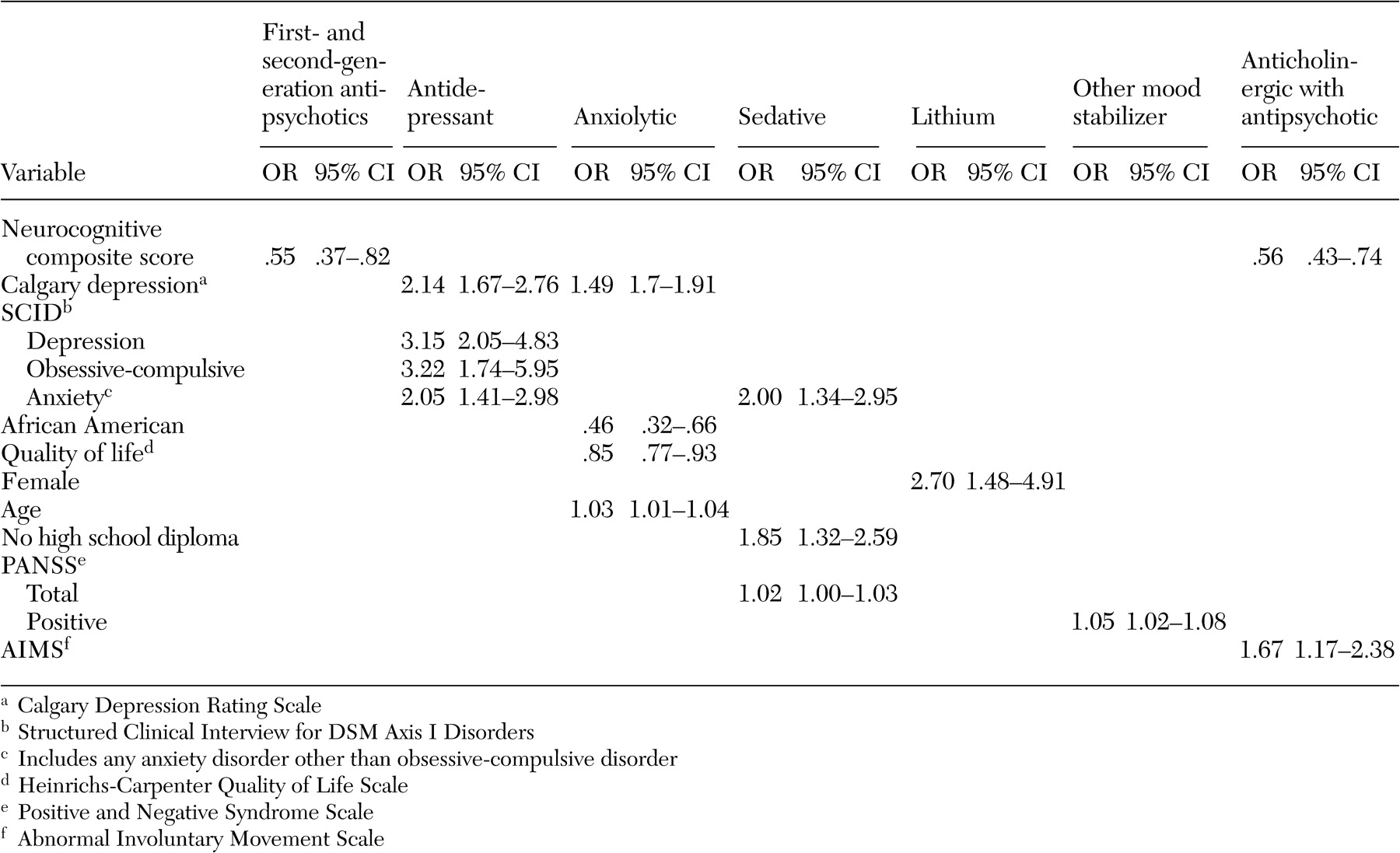

A broad array of factors was associated with concomitant psychotropic treatment of patients with schizophrenia in this trial. With respect to demographic predictors of concomitant use of psychotropic medications, African-American participants received fewer concomitant psychotropic medications and anxiolytics, whereas women received more concomitant psychotropic medications, especially antidepressants and lithium. Female patients may have been taking more concomitant psychotropic medications because women generally are better able to express their symptoms of anxiety and depression to their providers, which in this case may have resulted in an increase in prescriptions of concomitant psychotropic medications. Alternatively, the female patients perhaps were more likely to experience these symptoms. A prescriber bias is another possible explanation for this difference. Less frequent use of anxiolytics among African-American patients is consistent with findings of other investigators (

9,

34 ) and may reflect prescriber bias, economic factors, or less engagement in the mental health system (

34,

35 ).

Both the number of concomitant psychotropic medications and the use of antidepressants and anxiolytics had no association with positive or negative symptoms of schizophrenia but were associated with symptoms of anxiety and depression. The lack of an association of antidepressant or anxiolytic use with positive symptoms or potential confounders of depression, such as negative symptoms and extrapyramidal side effects, suggests that symptoms of depression and anxiety are components of the illness that are independent of positive or negative symptoms or side effects such as extrapyramidal effects. The increase in prescribing concomitant psychotropic medications to patients with symptoms of anxiety and depression suggests that physicians have become very responsive to treating these symptoms among patients with schizophrenia. This may in part be due to patients' complaints about these ancillary symptoms and patients' increased expectations of treatments to relieve them but may also reflect the physician's desire to ameliorate the feeling of demoralization and anxiety associated with having to deal with this chronic illness.

The association of more severe depressive symptoms with concomitant antidepressant use, in the form of higher Calgary depression scores, even after the analysis controlled for comorbid axis I diagnoses of depression and anxiety disorders, suggests that, at least with respect to depressive symptoms, concomitant use of antidepressants as used in this patient population was not fully effective. Because we do not have data on duration or dose of treatment with antidepressants, this lack of efficacy may be due to suboptimum dosing or inadequate duration of treatment with antidepressants. Alternatively, the addition of antidepressants to second-generation antipsychotics may not be effective in treating depression among patients with schizophrenia. This issue can be addressed only in a randomized controlled clinical trial of adjunctive antidepressant use in depressed patients with schizophrenia who are taking second-generation antipsychotics.

The efficacy of antidepressant treatment among patients with schizophrenia has been an issue of considerable discussion. It is confounded by the fact that depressive symptoms among patients with schizophrenia may reflect demoralization or be subsyndromal. On the basis of a stringent definition of

DSM-IV diagnosis of depression, 60 percent of patients with schizophrenia have an episode of major depression at some point in their illness course (

36 ). Depression has been associated with an increased risk of relapse, poor social adjustment, and suicide (

10,

36,

37,

38 ). The evidence with respect to the benefits of adding antidepressants to antipsychotic medication for treatment of depressive symptoms among stable outpatients with schizophrenia has been mixed (

10,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43,

44 ).

Unlike concomitant use of antidepressants or anxiolytics with antipsychotic medications, the use of mood stabilizers other than lithium and the use of sedatives were associated with more severe illness as indicated by higher PANSS scores. The association of use of these mood stabilizers with higher positive symptom scores suggests that these adjunctive medications are being used to treat patients with more positive symptoms. There are no randomized controlled studies of the persistent benefits of adjunctive divalproex compared with antipsychotic monotherapy after treatment of an acute exacerbation of schizophrenic illness.

A primary finding with respect to antipsychotic polypharmacy was that individuals who were treated with more than one antipsychotic medication had a lower neurocognitive composite score. It is possible that the association of antipsychotic polypharmacy with lower neurocognitive scores was a treatment side effect, perhaps caused by an increase in anticholinergic side effects. It is also possible that patients with more severe cognitive problems were more likely to be treated by antipsychotic polypharmacy, perhaps because of more partial adherence problems.

Although there is clear evidence that anticholinergic medications are effective in the treatment and prevention of acute extrapyramidal side effects (

45,

46 ), the need for long-term anticholinergic use among patients receiving antipsychotics is less clear (

47,

48 ). Therefore, assessing the side effect liability of such an intervention is critical. Our finding of greater neurocognitive impairment among patients with schizophrenia who were treated with anticholinergics is consistent with prior reports that anticholinergic agents impair several domains of cognitive functioning, including attention, declarative memory, verbal memory, and spatial working memory (

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55 ).

Although we do not know whether antipsychotic polypharmacy is a cause or a result of the neurocognitive impairment, the association of poor neurocognitive functioning with both antipsychotic polypharmacy and anticholinergic medications has important clinical implications. Evidence suggests that cognitive functioning is a core part of the pathology of schizophrenia (

56,

57 ), and those cognitive problems may persist even when psychotic symptoms are in remission (

58 ). These cognitive deficits may cause more social and vocational disability than positive or negative symptoms and may play a role in relapse and rehospitalization (

57,

58,

59,

60 ).

Many of the concomitant prescribing patterns in treating patients with schizophrenia with persistent psychosis, anxiety, depression, and cognitive deficits are not robustly supported by evidence in the literature. Therefore, such prescribing is likely driven by inadequate response to monotherapy or unmet treatment needs among these patients. The data presented in this study suggest that better treatments for the depression, anxiety, and cognitive deficits of patients with schizophrenia need to be developed. In addition, the most frequent concomitant prescribing practices should be tested empirically in randomized controlled clinical trials.