Approximately half of the people with severe mental illnesses—schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression—experience a co-occurring substance use disorder (abuse or dependence) at some point in their lifetime (

1 ). People with dual disorders experience worse outcomes than those with single disorders (

2 ). Integrated dual disorders treatment provides comprehensive, stagewise services to address the serious mental illness and the substance use disorder together in one comprehensive treatment package (

3 ).

Although a large number of studies have shown that this or similar integrated programs improve many outcomes for consumers (

4 ), the findings are not consistent. The more rigorous studies, summarized by Jeffery and colleagues in a Cochrane Review (

5 ), demonstrated that integrated treatment was superior to comparison treatments on some outcomes but not others and varied from study to study. Despite a growing interest in integrated treatment, practices that hold promise for persons with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, such as integrated dual disorders treatment, are still not widely available in public mental health settings (

6,

7 ).

Although a large body of research has evaluated some aspects of implementing programs in health and human services, less is known about implementation in public mental health settings. Fixsen and colleagues (

8 ) recently reviewed and summarized this literature on practice implementation, concluding that facilitators and barriers to the adoption of new programs can occur at multiple levels and that significant research gaps remain. Notably, of the 743 relevant articles they reviewed, 20 reported the results of experimental studies. These implementation studies took place in education, managed care, and medicine, rather than in public mental health settings. Research that has thus far documented implementation of programs in public mental health settings has been primarily case studies, summaries, and guidelines based on practical experience of implementation (

9 ).

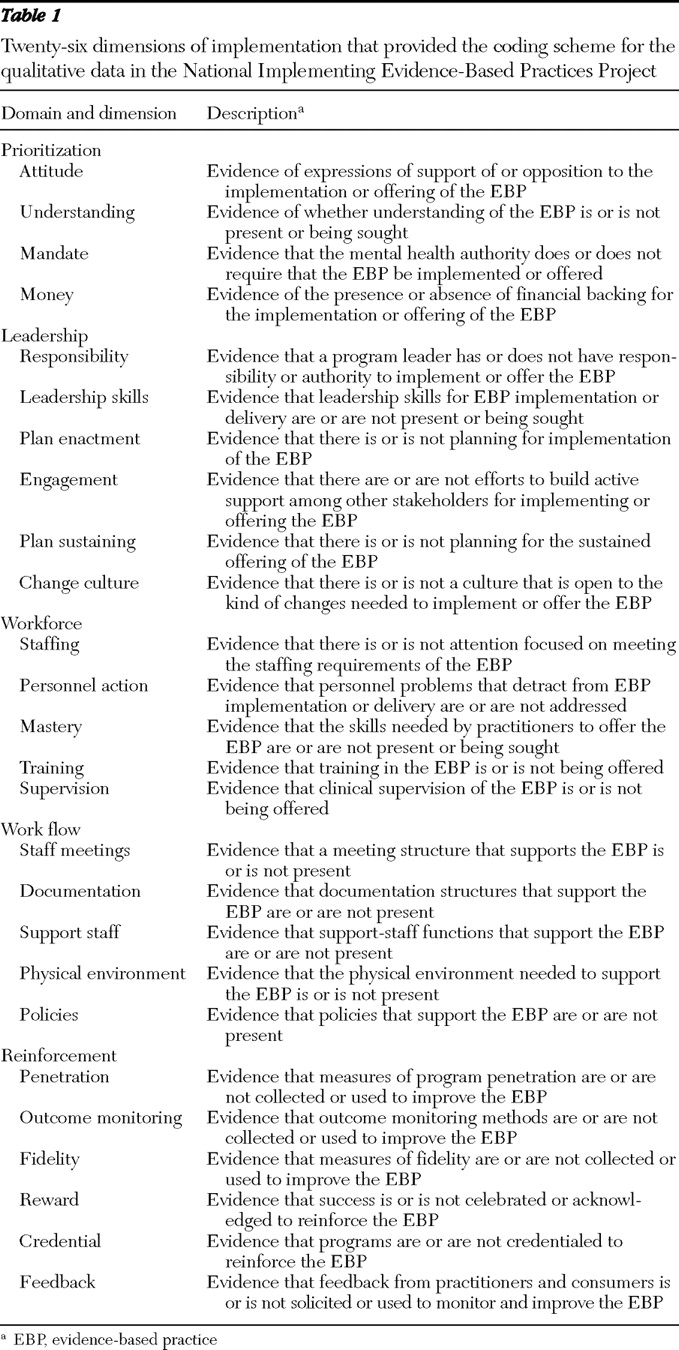

To learn more about service implementation in public mental health settings, the National Implementing Evidence-Based Practices Project investigated the implementation of five psychosocial practices in 53 routine mental health settings across eight states.

Implementation was assisted by an intervention package that included provision of a toolkit and access to a consultant-trainer for two years. Fidelity to each service model was measured at six-month intervals over two years and at a two-year follow-up. The initial analysis of implementation in this parent study found that more than half the sites were able to implement one of the five practices with high fidelity to the model of practice, but variation occurred across practices (

11 ). Integrated dual disorders treatment was one of the practices that fewer organizations implemented with high fidelity. Although several other reports have addressed some aspects of implementation from the parent study (

12,

13,

14 ), this report describes the extent to which organizations implemented integrated dual disorders treatment. This study then used qualitative methods to elucidate concomitant facilitators and barriers to implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment.

Results

The mean±SD integrated dual disorders treatment fidelity score at the 11 sites rose from 2.41±.55 at baseline to 3.42±.54 at 24 months (paired t test=-3.67, df=10, p=.004). (Possible scores range from 1 to 5, with higher scores indicating greater fidelity.) At the two-year point, two sites achieved high fidelity (a score of ≥4.0), six sites achieved moderate fidelity (≥3.0 and <4.0), and three sites remained at low fidelity (<3.0).

The main facilitators and barriers for each site that emerged from the second layer of analysis are summarized in

Table 2 . Five common themes then emerged in the third step of analysis: administrative leadership, consultation and training, supervisor mastery and supervision, chronic staff turnover, and finances. Each theme could influence implementation positively or negatively, depending upon its presence and quality.

Leadership

Administrative leadership was noted as a significant factor in implementation at every site. Successful sites tended to have a committed midlevel leader who had sufficient authority to make changes within the organization. Three components of leadership emerged: attitude, priority, and action.

Administrative leaders' attitudes set the tone and modeled appropriate staff responses to the challenges of starting a new service. Attitude alone, however, was insufficient. Leaders at successful (high-fidelity) sites made implementation a priority among their myriad, competing responsibilities, and they took action by making administrative and policy changes to implement the new practice. Action steps varied, including hiring, changing, or firing staff; changing the structure and focus of supervision; changing the treatment plan formats; and implementing new policies and practices for screening for and assessing substance use. Leadership action overcame barriers, such as staff turnover, in the implementation process. Notably, many of the successful agencies assigned implementation leadership to two administrators, one with administrative skills and one with advanced clinical expertise, who shared leadership tasks.

Organizations that implemented the service with low fidelity experienced problems with leadership. Some had enthusiastic leaders who, amid competing demands, were unable to prioritize implementation and take facilitative action. As one steering committee member put it, "The agency takes on these projects without allocating internal resources to make them succeed." Other organizational leaders appeared unable or unwilling to take action to implement the practice, despite the agency's agreement with the state authority or training center.

Consultation and training

Successful organizations utilized the consultant-trainer for two key functions: consultation for initial and ongoing implementation plans, including the type and timing of implementation activities; and training staff and leaders in the information and skills necessary to deliver the service. Consultation efforts varied; some efforts focused on initiating facilitators, and others focused on overcoming a variety of barriers. At some sites, consultation focused on policies and organizational structures to support the practice, while at other sites consultation focused on helping administrators learn leadership and supervisory skills.

Because the delivery of integrated dual disorders treatment requires skills in assessment and counseling that many public mental health clinicians may not have—for example, motivational interviewing and substance abuse counseling—the agencies either hired staff who possessed these skills or, in most cases, trained existing staff. Successful sites supplemented classroom training with regular supervision (see next section). At some centers, the consultant-trainer attended team meetings to provide supervision between monthly classroom-style trainings; at other centers, agency leaders were able to function in this key capacity.

Although many informants reported that the toolkit materials were helpful, most stated that the materials were less important than interactions with the consultant-trainer. Many project leaders made such comments as, "It's easier to call (or e-mail) someone than to look it up." The presence of the consultant-trainer was viewed as encouraging and appeared to boost morale during the challenges of organizational change.

Although skilled consultation to the agencies was helpful, unskilled consultation was harmful. In some cases, a consultant-trainer did not work well with leaders and appeared to confuse and hinder the implementation process. In addition, some low-fidelity sites received poor-quality training or simply did not allow employees to attend training.

Supervisor mastery and supervision

Many observers noted that clinical leaders require mastery of service-specific knowledge and skills in order to provide ongoing staff training and supervision. Most leaders developed these skills during the study. As one implementation monitor stated, "Supervision played a key role in the success of the integrated dual disorder treatment team."

The absence of high-quality clinical supervision was a common barrier observed in organizations with moderate or low fidelity.

Staff turnover

Many of the 11 organizations experienced significant staff turnover. In some, change in staffing facilitated implementation by moving unwilling staff to other positions, terminating incompetent staff, or hiring new staff who were willing and competent. Abrupt turnover of multiple staff was perceived as a barrier, although several organizations overcame this problem and attained reasonably high fidelity by immediate rehiring and training. Chronic staff turnover, however, appeared to be a much more difficult barrier, creating heavier training and supervisory challenges that some leaders were unable to meet. In addition, some of these teams were short-staffed for long periods, resulting in high caseloads. One case manager stated, "We are so overwhelmed we don't have time to practice the [integrated dual disorders treatment] techniques." It appeared in some cases that staff turnover was related to leadership problems with hiring, supervision, and other implementation support. One organization with chronic turnover was able to accept advice from the consultant-trainer to change hiring practices to reduce turnover, including utilizing team members in the hiring process, allowing job candidates to shadow experienced practitioners, and providing additional supervision to new practitioners.

Finances

In organizations that implemented the model with low fidelity, staff and leaders often expressed concern about the financial implications of making organizational changes, including allotting time for staff training, providing supervision, and reducing caseload size. One project leader stated, "Every time I've got a clinician sitting in a meeting … it's costing me money." These concerns occurred despite some funding (less than $10,000) to defray implementation costs and the provision of free training and consultation. In one state a simultaneous initiative to implement assertive community treatment competed with the implementation of integrated dual disorders treatment, in part because additional funds were offered for assertive community treatment implementation. This situation led one organization to abandon integrated dual disorders treatment implementation entirely. The program leader stated, "We are going to do whatever they … pay for."

At least one financially strapped organization was nevertheless able to overcome this barrier with leadership priority and consultation, implementing the service model with excellent fidelity. Successful organizations reported that their treatment teams were financially viable because Medicaid and Medicare payments for the clinical services covered the cost of running the services in those agencies.

Other facilitators and barriers

Several other themes arose that deserve mention. One facilitator embedded in this model of implementation was the use of regular fidelity measures to assess service quality and to provide feedback to leaders. Leaders at successful sites used these reports to develop action plans to further their implementation efforts. Another important facilitator was the integration of the agency's quality improvement actions with the implementation efforts. A third was each organization's relationship with the state or county mental health authority, which could help or hinder the process.

Discussion

Integrated dual disorders treatment was implemented with varying degrees of success at the 11 participating organizations. We found that facilitators and barriers, consistent with other independent reports from this project (

13,

20 ), occurred at the clinician level (staff skills and turnover), at the organization and administration level (leadership and supervisor mastery and supervision), at the level of the implementation model (consultation, training, and fidelity feedback), and at the environmental-state authority level (financing and the relationship with the mental health authority).

This study confirmed research in other fields suggesting the need for multilevel active implementation efforts and at the same time highlighted the importance of the organization's administrative leader and of the consultant-trainer. Even with intensive efforts at multiple levels, however, most organizations did not achieve high-fidelity implementation. Integrated dual disorders treatment is a complex service that contains multiple components and requires change at the provider, organization, and environment levels. For these reasons, this service may be more difficult to implement than single-component practices, such as cognitive therapy to treat major depression.

Financial concerns and financing emerged as a barrier that has particular salience in the current public mental health environment. Financing is related to the other facilitators and barriers and therefore must be addressed by systems wishing to implement these programs. First, federal and state mental health authorities that desire high-quality service implementation must provide adequate reimbursement for these services (

21 ), or provider organizations simply will not deliver them. Second, integrated dual disorders treatment requires skills that may be new to many public mental health providers (for example, substance abuse counseling and motivational interviewing) as well as structural change (for example, lower caseloads for workers who treat clients with dual disorders and the provision of group therapy). Thus organizations that are starting to implement the service should plan for temporary reductions in billing while staff members take time from direct service delivery to learn new skills and to restructure services and systems. Mental health authorities wishing for broad implementation should expect modest lulls and provide financial support for organizations during this period.

Third, mental health authorities and organizations must fund mechanisms to monitor fidelity or quality of service delivery, which can be aligned with ongoing quality improvement strategies (

22 ). The regular conduct of fidelity assessments and immediate feedback to leaders regarding fidelity was an inherent part of implementation that also required additional administrative staff time, which affects the cost of providing services. Finally, financial incentives to encourage organizations to implement evidence-based practices should be utilized (

23 ). Two other reports addressing state-level activities related to implementation in this large project confirmed that attention to financing and monitoring at the state level facilitated implementation within the organization (

12,

13 ).

This study used established qualitative research methods to elucidate facilitators and barriers at a range of organizations in several states. However, the study has several potential limitations. First, all the participating organizations volunteered to implement the service, potentially biasing the outcomes toward more positive results than would occur if we had, for example, attempted to implement the service statewide in all three states. In addition, this study assessed only one model of implementation, which used toolkit materials and an in-person consultant-trainer. Other models of implementation might result in different rates of success as well as different facilitators and barriers.