It is widely acknowledged that sub-Saharan Africa is deficient in providing prompt and effective professional mental health services, which are needed to avoid chronic illness and the establishment of irreversible sequelae. Most (approximately 70%) mental health services in Nigeria are delivered through unorthodox means, such as religious organizations and traditional healers (

1 ). Whether this practice is due to the unavailability of mental health services or to nonutilization of the few available services is not known. There are indeed cross-cultural variations in the pathways to caring for mental health problems (

2 ).

Because people with mental illness and their caregivers are likely to share the beliefs held in their society in regard to treatment of mental illness, it would be helpful to understand the public's preferences about treatment in order to fully evaluate help-seeking behavior. Studies from Western cultures have revealed that psychotherapy is the preferred treatment option in Germany, Canada, and Eastern Europe (

3,

4,

5 ), whereas social treatment is preferred in Turkey (

6 ). Available studies in sub-Saharan Africa have suggested a preference for traditional and spiritual healers (

7,

8,

9 ). However, these surveys are few, were done in single centers, used small samples, and did not examine the correlates of such treatment preferences by the public. This study aimed to assess the preferences of the southwestern Nigerian public in regard to the treatment of mental illness and to evaluate the factors associated with their preferences.

Methods

Participants were selected from three selected communities in southwestern Nigeria through a multistaged probability sampling technique. The communities were selected to be representative of an urban community (more than 20,000 households), a semiurban community (12,000–20,000 households), and a rural community (less than 12,000 households). These classification levels were in accordance with the National Population Commission (

10 ), which conducted the 2005 population census in Nigeria. The first stage consisted of random selection of seven enumeration areas from each of the three communities. These areas are geographical units demarcated by the National Population Commission (

10 ), with each area consisting of 100–120 household units. The second stage involved counting the houses in each area. When more than one family was living in a household, one family was selected by balloting. The third stage involved the selection by balloting of one adult (older than 18 years) from each family for the interview. From this process a total of 2,342 participants (845 from urban, 782 from semiurban, and 715 from rural communities) were targeted for the interview.

The study instruments were translated into Yoruba with a back-translation method. The process involved two independent panels that each consisted of a psychiatrist and a Yoruba linguist.

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants after the aims and objectives of the study had been explained. The Ethics and Research Committee of the Obafemi Awolowo University Teaching Hospitals Complex approved the study protocol. A group of 21 trained research assistants who were medical students in psychiatry positions and fluent in both English and Yoruba languages administered the questionnaire to the participants. Participants who could read were given the questionnaires in their preferred language for self-completion. For participants who could not read, the interviewers read the questions out loud and recorded the participants' answers.

Between January and February 2006, the participants completed a semistructured questionnaire that inquired about sociodemographic data, including age, sex, marital status, religion, ethnicity, highest education obtained, and occupation, as well as information in the following areas.

For familiarity with mental illness participants indicated whether they had ever had contact with or ever provided care for someone with mental illness and whether they had a family member or friend who had or had had mental illness.

Respondents' attributions of the possible causal factors of mental illness were assessed by responses to nine items detailing possible causes of mental illness. The causes included psychosocial factors (substance and alcohol abuse and dependence, life stresses, and personal shortcoming or lack of willpower), supernatural factors (witchcraft, sorcery, evil spirits, God's will or divine punishment, and destiny or bad luck), and biological factors (heredity, brain injury, contact with persons with mental illness, and childbirth).

The nine items were drawn from a list of 21 possible causes of mental illness suggested earlier by psychiatric patients, their relatives, community opinion leaders, traditional healers, spiritual healers, and the lay public. A panel of six persons, consisting of a psychiatrist and a representative from each stakeholder category in the list just mentioned, reduced the suggested 21 possible causal factors to nine items, which were sorted into three groups. Although the questionnaire seemed to have face validity, its psychometric properties had not been formally examined. On a 4-point Likert scale (not a cause, rarely a cause, likely a cause, and definitely a cause), the respondents indicated how relevant they considered each potential cause to be. Responses of "likely a cause" and "definitely a cause" were counted as endorsing a cause. For clearer presentation, the average endorsement of each group of psychosocial, supernatural, and biological factors was computed and based on this criterion; participants endorsing more than the mean (+2 standard deviations) for each group were regarded as significantly endorsing the causal group. Endorsement of more than one item in a group was regarded as significant endorsement of the group.

The personal attributes that respondents associated with persons with mental illness were assessed via a questionnaire designed by Angermeyer and Matschinger (

11 ) that covered two important stereotypes of mental illness: perceived dangerousness and perceived dependency. The perceived dangerousness stereotype included five attributes: unpredictability, lack of self-control, aggressiveness, ability to instill fear in others, and dangerousness. The perceived dependency stereotype included three attributes: neediness, dependence on others, and helplessness. Respondents were asked to indicate whether these attributes apply to persons with mental illness. Again, for clear presentation of results and ease of computation, the sample was dichotomized on the basis of average endorsement of each item of the stereotype group. Participants who scored more than the mean (+2 standard deviations) on each stereotype group were considered to have significantly endorsed that stereotype group. From this result, endorsement of more than two items on the perceived dangerousness stereotype group (with five items) and more than one item on the perceived dependency group (with three items) was regarded as significant endorsement of that stereotype group.

Respondents were asked to choose among Western medicine (hospitals, psychotropic medication, and psychotherapy), traditional practices (herbalists and other traditional healers), and spiritual healing (prayers in churches, mosques, and other places of worship) as their preferred treatment option for mental illness.

The data were analyzed with SPSS, version 11. For ease of analysis, most of the variables were grouped. Results were calculated as frequencies (in percentages), means, medians, and modes. Group comparisons were by chi square test. Significance was established at .05 or less. Logistic regression analysis was used to calculate the variables that were independently associated with the preferred treatment option, and odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Results

Of the 2,342 persons targeted for participation, only 2,112 were met at home despite repeated visits. Of this number 34 persons refused participation, and 2,078 respondents were successfully administered the questionnaires. The sociodemographic details of the respondents revealed that most were under age 50 (N=1,278, or 62%), male (N=1,133, or 55%), married (N=1,289, or 62.0%), Christian (N=1,130, or 54%), and from the Yoruba ethnic group (N=1,869, or 90%). A large percentage had secondary school education (N=821, or 40%) and were skilled laborers (N=826, or 40%).

Although about a third (N=612, or 30%) of the participants reported having a family member or friend with mental illness, only 228 (11%) had ever had contact with someone with mental illness, and only 102 (5%) had provided care for someone with mental illness. This could mean that many who reported having relatives and friends with mental illness actually had not had any contact with them. Furthermore, although psychosocial causation of mental illness was significantly endorsed by 912 (44%) respondents, supernatural and biological causations were significantly endorsed by 1,016 (49%) and 632 (30%) respondents, respectively. Also, the stereotype of dangerousness was significantly endorsed by 1,203 (58%) respondents, whereas that of dependency was significantly endorsed by 438 (21%) respondents.

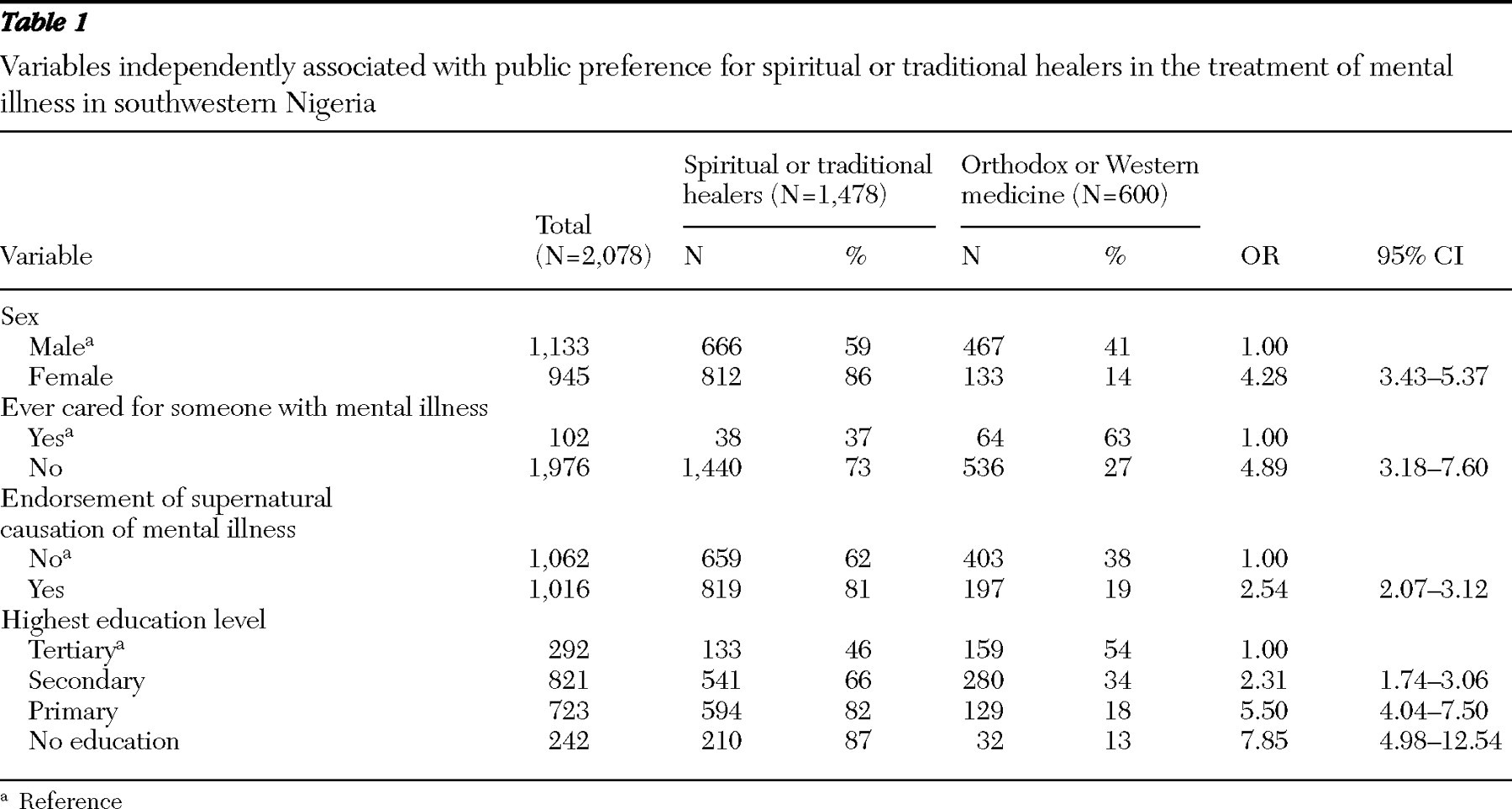

Analysis also showed that 844 (41%) respondents indicated spiritual healers as their preferred treatment option, whereas 634 (30%) indicated traditional healers and 600 (29%) indicated Western medicine. To calculate the factors associated with preference for unorthodox treatment options, we dichotomized the respondents into those with a preference for Western (orthodox) medicine (N=600, or 29%) and those with a preference for spiritual healers or traditional healers (N=1,478, or 71%). A binary logistic regression analysis was then done for the variables associated with preference for spiritual and traditional healers, with separate entries for sociodemographic variables (age, sex, marital status, religion, ethnicity, urbanicity, education level, and occupational status), familiarity variables (had contact with or ever cared for a person with mental illness and having a family or friend with mental illness), causal attribution variables (psychosocial causation, supernatural causation, and biological causation), and perceived stereotype variables (perceived dangerousness and perceived dependency).

Results of the logistic regression showed that the only factors independently associated with preference for spiritual or traditional healers included female gender (B=3.83, SE=.64, Wald

χ 2 =36.37, df=1, p<.001), lower level of education (B=4.04, SE=.50, Wald

χ 2 =65.47, df=1, p<.001), having never cared for someone with mental illness (B=3.09, SE=.42, Wald

χ 2 =53.04, df=1, p<.001), and significant endorsement of supernatural causation of mental illness (B=2.15, SE=.42, Wald

χ 2 =25.98, df=1, p<.001). The adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for the independently significant variables are shown in

Table 1 . Separate regression analyses for treatment preference, with gender factored out, showed a significant difference only for spiritual healers and no difference for traditional healers.

Discussion

We aimed to assess the public's preferred treatment option for mental illness in this survey, and it was evident that persons in our sample in southwestern Nigeria preferred alternatives to Western medicine for the treatment of mental illness. This is in line with previous studies in northern and western Nigeria that have suggested that care for mental illness is most often sought from traditional and spiritual healers (

7,

8,

9 ). It is known that most (approximately 70%) mental health services in Nigeria are provided through unorthodox means, such as religious organizations and traditional healers (

1 ). Traditional healers can recognize symptoms of mental illness, and they express strong beliefs in supernatural factors as a cause of mental illness (

12,

13,

14 ).

We also found that the factors that were independently associated with preference for spiritual or traditional healers included being female, having a lower level of education, having never cared for a person with mental illness, and endorsement of supernatural causal beliefs. Although no clear explanation could be offered for the gender difference in treatment preference, we hypothesized that women in southwestern Nigeria are likely to be more religious than their male counterparts and to believe more strongly than men in spiritual healing. This hypothesis was supported by further analysis of our data, which showed that the bulk of the gender difference was in the spiritual healers option alone, with no gender difference in the option of traditional healers.

As expected, our study showed that those who significantly endorsed supernatural causation of mental illness were more likely to seek help from spiritual or traditional healers. We have shown elsewhere that beliefs in supernatural factors are prominent in sub-Saharan Africa (

15 ). A strong belief in supernatural causation may also imply that offering Western medical care would be futile. We found a strong correlation between lower education and preference for spiritual or traditional healers. Lack of literacy may correlate with a poor understanding of mental illness and a belief in supernatural causes.

Our study showed that those who had never cared for someone with mental illness had a significant preference for spiritual or traditional healers. A majority of patients who seek care in Western-style facilities in Nigeria seek help or receive treatment elsewhere before presentation, most often from spiritual healers, traditional healers, or both (

13,

14 ). A possible explanation for this finding is that caregivers for persons with mental illness are likely to have helped the patient through the pathway to care and thus would be in a better position to compare the various treatment options.

Our findings have clinical implications for patients' help-seeking behavior and their compliance because these behaviors are related to the views of the society in which they live.

Our study assumed that attitudes, values, and belief systems in the community transmitted by family, kinship, and friend networks influence the manner in which an individual defines and acts upon symptoms and life crises. Patients with a mental illness and their caregivers tend to share the beliefs commonly held by the society where they live, at least at the beginning of help seeking. In addition, public opinion may shape the attitudes of those in direct contact with individuals with mental illness.

There were a number of limitations to this study. First, one should be careful about generalizing the results of this study to other ethnic groups in Nigeria and sub-Saharan Africa. There are several cultural differences in Nigeria and sub-Saharan Africa that may affect people's beliefs and attitudes toward mental illness and help seeking. Information is required for each cultural group, and a larger, multicentered, cross-ethnic study would be helpful. Also, causality cannot be determined because this was a cross-sectional study and the related factors were just correlates. This study also focused on mental illness in general, whereas it is known that the public has different views and attitudes toward different specific mental disorders. The strengths of the study were its large sample and in its being community based and coming from a culture not well studied.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have shown that the public in southwestern Nigeria preferred alternatives to Western medicine for the treatment of mental illness, and these views were mainly held by women, persons who had never cared for someone with mental illness, persons with lower education, and those who significantly endorsed supernatural causation of mental illness. Because professional mental health services are poor in Nigeria, efforts to improve such services must consider and seriously address the beliefs and preferences of the public in regard to mental health treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

The authors report no competing interests.