Suicide is the leading cause of premature death among patients with schizophrenia (

1). The lifetime prevalence of completed suicide in this patient group has been estimated at 10 percent (

2). The prevalence of suicide attempts in this group is reported to range from 18 to 55 percent (

2).

The risk factors for suicide among patients with schizophrenia include male gender, age under 30 years, never-married marital status, history of depression, previous suicide attempts, history of substance abuse, and recent discharge from the hospital (

3). Patients experiencing hopelessness and fear of disintegration are also at high risk for suicide.

Depression appears to be an important risk factor for suicide attempts. Jones and associates (

4) found that patients with schizophrenia who also experienced depression had a significantly greater likelihood of attempting suicide. In their study, subjects' scores on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression correlated with suicide attempts, while the sum of positive and negative symptom items from the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale did not. Increased risk of suicide attempts is also associated with a high level of education, good premorbid adjustment, the presence of good insight, and the awareness that desired expectations might not be met (

5). Low concentrations of 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid (5-HIAA) in cerebrospinal fluid have been reported among patients with schizophrenia who attempt suicide (

6).

The study reported here explored the association between psychosocial variables and symptoms among patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder who attempted suicide and patients without such a history.

Methods

The sample includes subjects consecutively evaluated at the University of Iowa Mental Health-Clinical Research Center over the period from 1990 to 1994. Patients were recruited into the research protocol from the University of Iowa Hospital after they provided written informed consent. The subjects were typically admitted to the research center for a period of four to six weeks. All patients met DSM-III-R criteria for chronic schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Patients were excluded if they had mental retardation or dementia or had had a lobotomy. None had serious medical or neurological illnesses. The 336 subjects included in the study were assigned to one of two groups based on whether they had a lifetime history of a suicide attempt.

Data were collected using the Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History structured interview, an instrument developed at the clinical research center to assess patients with psychotic and mood disorders. The instrument provides data on patients' premorbid adjustment, as well as sociodemographic data on educational achievement, work history, and social history. Study participants' positive and negative symptoms were assessed using the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms and the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms. All ratings were conducted by trained research nurses. The reliability of the raters was repeatedly assessed. Additional information was obtained from patients' family members and significant others and from medical records.

Dichotomous variables were analyzed using Fisher's exact tests. They were sex, single or married marital status, and a history of an axis II diagnosis or drug and alcohol abuse. T tests were used to analyze the continuous variables. They were social class and educational achievement of parents and subjects' premorbid adjustment; educational performance; age at onset of the schizophrenic disorder and at first hospitalization; level of positive, negative, and disorganized symptoms; and the number of lifetime depressive episodes.

Results

All 336 subjects were Caucasian. A total of 235 were male (69 percent), and 252 were single (75 percent). The majority of the subjects were unemployed (N=250, or 74 percent) at entry into the study.

Ninety-eight patients (29.2 percent) had made one or more suicide attempts, and 238 patients (70.8 percent) had never attempted suicide. The number of attempts ranged from one, for 38 patients, or 11.3 percent of the study sample, to 20, for one patient, or .3 percent of the sample, with the frequency declining as the number of attempts increased.

The suicide attempters were significantly younger than the nonattempters at onset of their illness and at their first hospitalization. Their mean±SD age was 19.8±5.2 years at onset of illness, compared with 21.9±5.7 years for the nonattempters (t=3.9, df=334, p= .002). When they were first hospitalized, the mean age of the suicide attempters was 21.2±7.7 years, compared with 23.3±6.3 years for the nonattempters (t=2.7, df=285, p=.007).

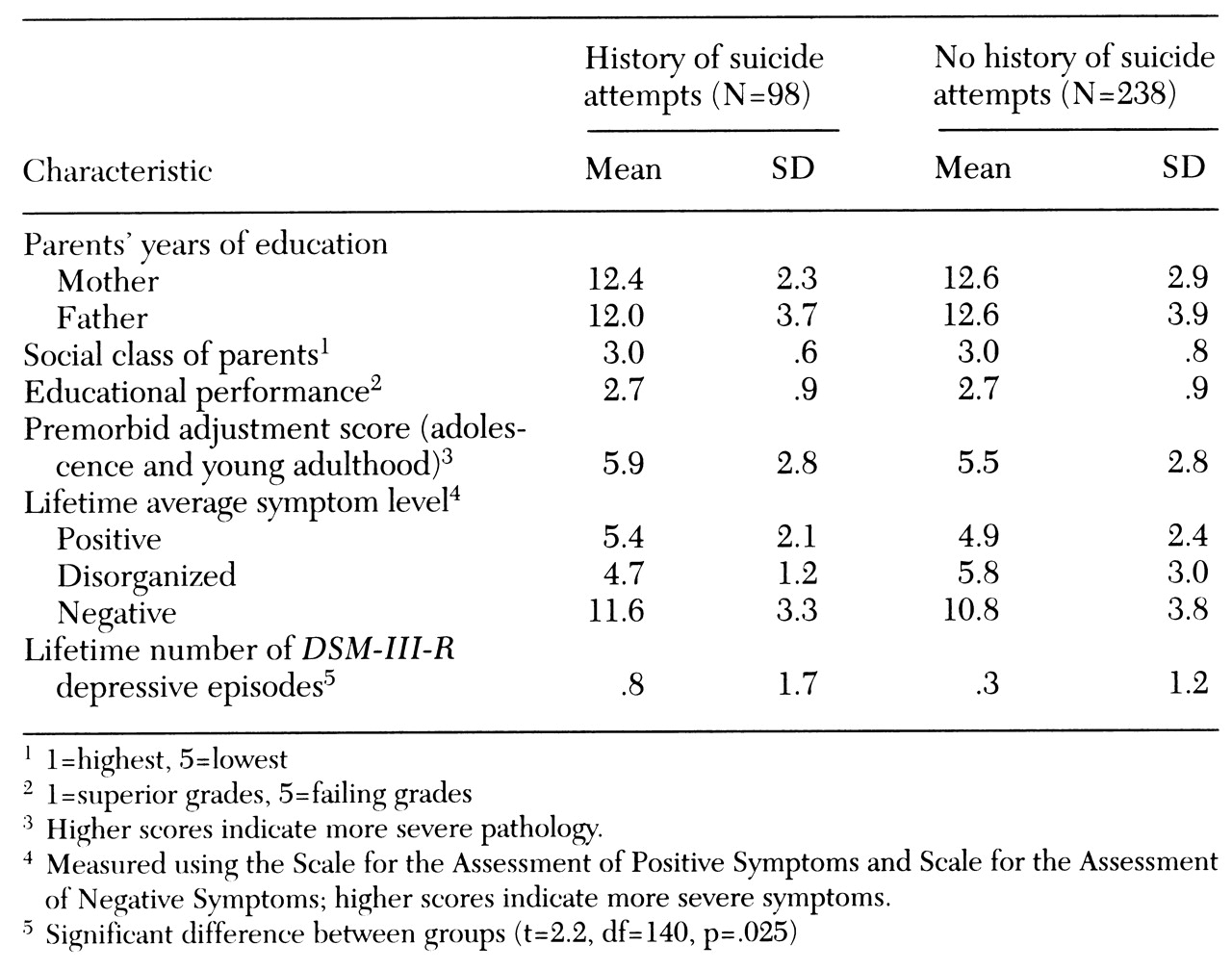

As

Table 1 shows, the two groups did not differ significantly in psychosocial factors such as educational performance, social class or educational achievement of parents, or in premorbid adjustment score or level of positive, negative, and disorganized symptoms. No differences between groups were found in the proportions with a lifetime history of an axis II

DSM-III-R diagnosis or of drug or alcohol abuse. However, as

Table 1 shows, the two groups differed significantly in the number of lifetime depressive episodes (t=2.2, df=140, p=.025).

Subjects with a lifetime history of suicide attempts were compared with nonattempters using an analysis of variance with a Bonferroni correction. The number of lifetime depressive episodes was the only variable that showed a significant difference between groups (F=6.65, df=1,334, p=.01), with the suicide attempters having a greater number of lifetime depressive episodes than the nonattempters.

Discussion

In this large sample consisting predominantly of single male patients, a substantial number of patients—29.2 percent—had made a suicide attempt. This proportion is consistent with reports from studies by Planansky and Johnston (

7) and Dassori and associates (

8), in which 25 percent and 32 percent, respectively, of the patient samples had attempted suicide.

In our study sample, the number of lifetime depressive episodes was significantly associated with suicide attempts. Similarly, Drake and associates (

9) found evidence of depressed mood among 80 percent of a series of patients with schizophrenia who completed suicide and among 52 percent of patients who attempted suicide. Hence depression can be seen as an important risk factor for suicidal behavior among patients with schizophrenia. In assessing patients, the clinician should distinguish depressive symptoms from the signs of antipsychotic-induced parkinsonism, the negative symptoms of schizophrenia, and the effects of institutionalization.

In our sample, the patients who attempted suicide were younger at their first hospitalization than patients who had not attempted suicide. This finding suggests that the patients who attempted suicide had more severe psychopathology, which is associated with an earlier age of illness onset, although our analysis showed no significant differences between suicide attempters and those who did not attempt suicide in current symptom levels. A chronic course of illness and poorer prognosis are also associated with earlier onset.

Of interest, we did not find an association between suicide attempts and drug or alcohol abuse. This finding is somewhat counterintuitive, as data for patients with nonschizophrenic disorders suggest that those with co-occurring alcohol abuse and depressed mood have an exceptionally high risk of suicide (

10). Our finding may be due to the low base rate of substance abuse in our study population, which included many patients who lived with their parents on farms or in small towns. Homelessness was not particularly an issue with this group.

Conclusions

The study results suggest that lifetime depressive episodes and an earlier age of onset of schizophrenic disorders may be important risk factors for suicidal behavior among patients with those disorders. Depressive symptoms among patients with schizophrenia should be recognized early and treated with medication. The results also suggest that psychosocial variables may be less valuable predictors of suicidal behavior than clinical variables.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants MH-31593, MH-40856, and MH-CRC-43271 from the National Institute of Mental Health and by the Nellie Ball Trust Fund, administered by Iowa State Bank and Trust Company.