Much has been written about the barriers at the state and local levels to providing integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment for people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders (

1—

6). The structural barriers include the lack of common administrative structures for mental health and substance abuse services, categorical funding for services (mental health dollars versus substance abuse dollars), differential licensing requirements for treatment programs, and an overall scarcity of treatment resources (

1). In addition, the two systems have different treatment philosophies and different approaches for training and credentialing providers.

Because of these differences, providers from the two service sectors may disagree on appropriate treatment strategies for people with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. Due to providers' concerns about scarce resources, requests for collaboration often are seen as attempts to encroach on another's "turf."

Principles of service integration in the treatment of people with co-occurring disorders have been written about for more than a decade and have been espoused in many communities. However, the problems that interfere with true coordination of services continue unabated in most settings. Therefore, it is especially noteworthy when a community's service delivery systems actually put the principles into action.

This paper describes a program in Maine that has developed collaboratives of providers, including mental health, substance abuse, public health, and other agencies, to offer coordinated treatment and support for people with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders. The paper also presents results of a mail survey of key informants involved with one collaborative who answered questions about the degree of service integration achieved by the program.

The experience in Maine

To improve the diagnosis and treatment of persons with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders, in 1992 the State of Maine funded the establishment of regional treatment collaboratives in four communities. The collaboratives are made up of mental health, public health, and substance abuse treatment providers; consumers and family members; private practitioners; representatives of municipalities and criminal justice agencies; providers of services to homeless people; and vocational rehabilitation providers. A major focus was building provider relationships across the service-sector boundaries, establishing a common language with which to communicate about the diagnosis and treatment of co-occurring disorders, and providing "cross-training" for administrators and staff of all agencies in the community, regardless of whether they participated in the activities of the collaborative.

One of the four collaboratives—the 22-member Cumberland County dual diagnosis collaborative in Portland—received funding in 1993 from the Bingham Program, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, and the Maine Office of Substance Abuse for a study of its efforts to develop coordinated treatment for people with comorbid disorders. The study included an assessment of the implementation of the Cumberland County collaborative and a survey of key agency informants to determine the extent of service integration achieved by the collaborative.

The implementation process

Critical to the collaborative's ability to work toward its goals were the following activities:

•

Inviting all relevant agencies to participate in the collaborative and keeping communication open when working through difficult issues

•

Using mechanisms such as monthly meetings and training staff in the activities of more than one agency to create and maintain a shared knowledge base and a common vision of the optimal service system for people with co-occurring disorders

•

Ensuring ongoing—rather than token—participation by consumers

•

Nurturing one-to-one relationships among service providers across service sectors.

Joint treatment planning, colocation of staff, and training across agencies allowed one agency to make use of the resources and expertise of another agency without an actual transfer of resources. Such transfers are often difficult because of the constraints of categorical funding.

Over the past four years, several large-scale service system changes have resulted from the systems-level work of the collaborative. The following are some examples:

•

Members of the collaborative identified housing as a major unmet need. Clients were often denied housing because of behavior related to substance abuse, even though they were in the early stages of substance abuse treatment. One agency in the collaborative took the lead, coordinating the efforts of mental health and substance abuse treatment providers to design a multiunit single-room-occupancy apartment program. Agencies share responsibility for staffing the program, which also employs peer counselors.

•

Traditional meetings of Alcoholics Anonymous in the community were largely unresponsive to and unsupportive of individuals who also had mental disorders. In the past, consumers had worked together to form "dual recovery anonymous" groups, but they had abandoned the effort because of low attendance. Consumers served by the collaborative asked agency staff members to assist them in designing self-help groups that would address recovery from both mental illness and substance use. Professional staff helped organize the groups and initially provided logistical support and guidance, although consumers retained primary responsibility for facilitating meetings.

•

The mental health community had been concerned that emergency room care for psychiatric crises was inadequate, especially for the increasing number of intoxicated mentally ill people who sought help from emergency rooms. Agencies in the collaborative formed a small working group to design a program that would divert persons with dual diagnoses from emergency rooms to more appropriate services in the community. The working group included consumers and staff from local hospitals, crisis hotlines, the police department, and the local emergency shelter and detoxification program. The shelter and detoxification program offered four beds. The local mental health agency trained shelter staff in the recognition of psychiatric symptoms and the identification of appropriate referral services, and staff from a mental health agency and a substance abuse agency helped train the police. The working group is developing protocols for diversion, involving both the police and the hospital emergency room staff.

The mail survey

Data on the extent of service integration achieved by the collaborative were collected in a structured survey mailed to key informants in each agency participating in the collaborative. The survey included 18 questions asking the respondent to rate on a 5-point scale the extent to which the agency's activities had been affected by its participation in the collaborative. Two major areas of activity—care of people with dual diagnoses and administrative and training activities—were covered. In addition, the survey included open-ended questions. The survey methods were based on earlier research on the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Program on Chronic Mental Illness and on mental health system interventions for children in the state of Maine (

7—

9).

The survey was mailed in April 1994 to all 22 agencies participating in the collaborative. Twenty agencies responded, for a response rate of 91 percent. The survey was repeated in May 1995, with a total of 19 respondents. The repeated measure was intended to show whether the collaborative had maintained, improved, or reduced integration of services over the course of the project.

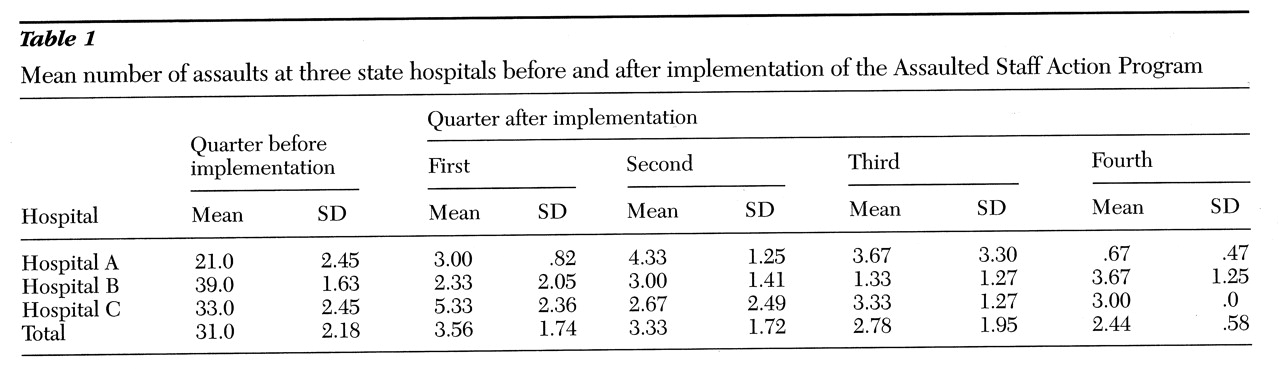

Table 1 shows the 18 structured survey questions and data on responses. Overall, the responding agencies reported in both years that they had exchanged a considerable amount of general information about services. Respondents indicated that they referred and received referrals from other agencies to a moderate degree. Specific activities such as joint assessments or joint case reviews were reported to occur less frequently than the general exchange of information about clients. To the question about the extent to which agencies jointly sponsored programs or services—an area that would reflect maximum coordination of effort—the average respondent rating indicated little or none of this type of activity.

Table 1 shows an increase from April 1994 to May 1995 in the average extent to which agencies referred clients to other agencies, received client referrals from other agencies, and conducted joint assessments of clients with dual diagnoses. However, the extent of collaboration in case conferences or reviews fell slightly between the two surveys. As for training and administrative activities, the extent to which agencies participated in joint training and jointly sponsored programs or services increased.

The relatively high scores on these areas of collaboration in 1994, as well as the stability of scores and increases in some in 1995, indicate that the collaborative is having an important impact on the capacity of mental health, substance abuse, and other community agencies to serve people with severe mental illness and co-occurring substance use disorders. In response to the open-ended questions in the 1995 survey, respondents said that their agencies had added more services and programs geared specifically for people with dual diagnoses, that the number of staff dually licensed in the mental health and substance abuse treatment fields had increased, and that their collaboration with other agencies had increased.

Conclusions

Developing a collaborative of providers to serve clients with co-occurring mental and substance use disorders offers a cost-effective approach to maximizing current resources and improving the local delivery of services. Communities that invest the effort to make changes in the way agencies work together can expect benefits to their own agencies and better care for the clients they serve.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Maine Office of Substance Abuse, the Bingham Program, and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.