Clinical depression occurs in individuals of all ethnic backgrounds, yet few published studies have assessed ethnic differences associated with antidepressant treatment. Findings suggest that black and Latino patients may be more likely to present with somatic complaints, whereas white patients are more likely to report affective or cognitive symptoms (

1,

2). Nonwhite patients may also differ from white patients in the frequency of side effects, as well as response and dropout rates during participation in antidepressant trials. However, findings on possible associations between ethnicity and treatment outcome have been inconsistent (

1,

3—

5). Given the limited number of studies and mixed findings, further research is needed to clarify the relationship between antidepressant treatment and ethnicity.

The study reported here examined ethnic differences in baseline manifestations of depression and treatment outcome among depressed HIV-positive patients participating in a clinical trial of fluoxetine. We analyzed data from a sample of patients in the eight-week randomized, placebo-controlled trial to assess whether ethnicity was related to treatment outcome (measured as study completion and treatment response) and to reported side effects.

Methods

Patients who were HIV-positive and who had an untreated axis I depressive disorder were eligible for the study. Exclusion criteria included current substance dependence, bipolar disorder, psychotic symptomatology, significant suicidal risk, severe cognitive impairment, or unstable medical conditions. Patients had to be under the care of a physician experienced in treating HIV and had to give informed consent.

Our research team verified the patients'

DSM-IV diagnoses of depressive disorder using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (

6). The 21-item version of the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D), which assesses both cognitive and vegetative symptoms (

7), was used to measure severity of depressive symptoms. The Clinical Global Impressions Scale (CGI) was used to rate the degree of improvement and overall response. The Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), a 53-item self-report scale (

8), was used as a measure of global distress. CD4 cell count was used as a marker of immune status; the assay was obtained via Metpath (now called Quest) Laboratories in Teterboro, New Jersey.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive fluoxetine or placebo in a 2:1 ratio—two-thirds were assigned to receive fluoxetine—and were seen weekly for eight weeks. The starting dose was 20 mg per day; doses were increased incrementally between weeks 4 and 8 to 80 mg per day as clinically indicated. Clinical response at week 8 was defined as a CGI rating of 1, very much improved, or 2, much improved, and at least a 50 percent decrease in the HAM-D score.

Independent two-tailed t tests and univariate analysis of variance models were used to assess differences between groups for continuous variables, and chi square analyses were used with categorical variables. Multiple regression analysis was used to assess predictors of study completion.

Results

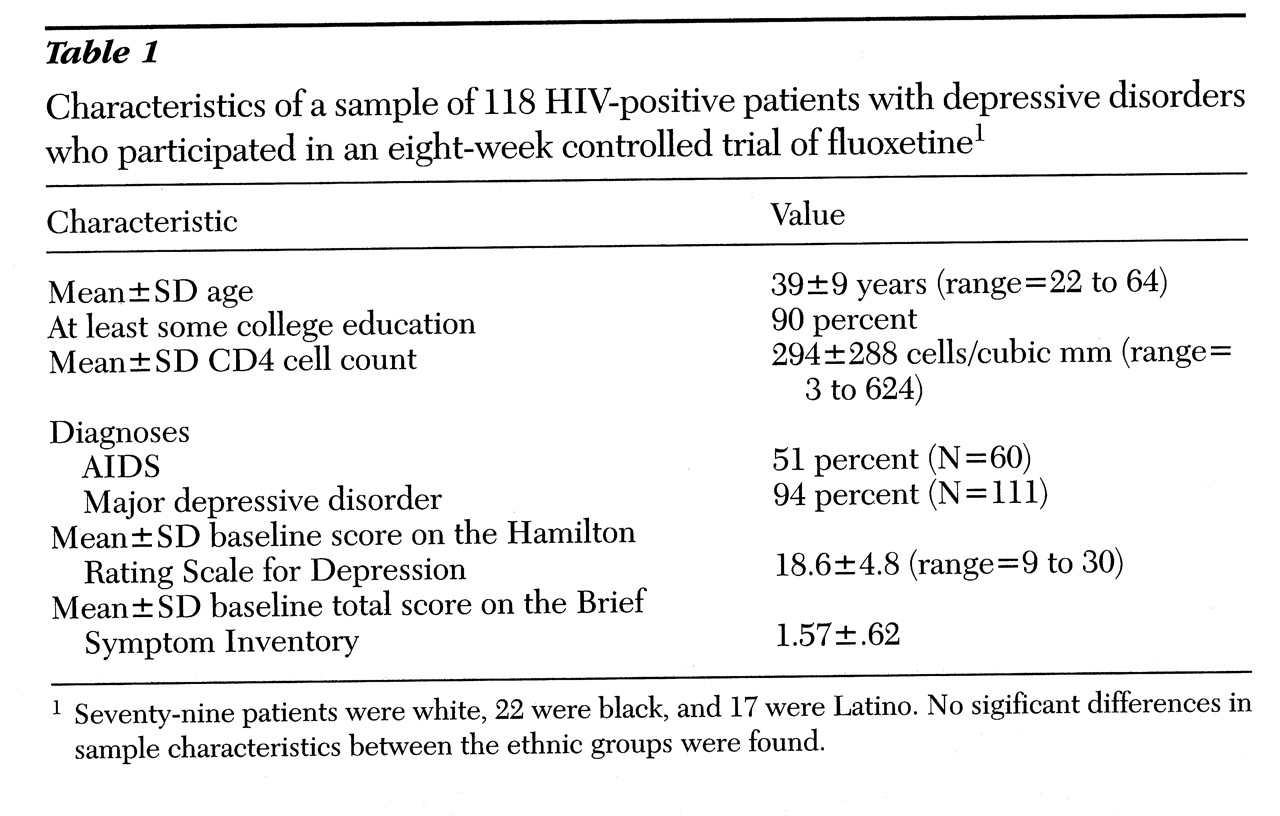

A total of 118 patients, 116 men and two women, were enrolled in the study between 1993 and 1996. Two-thirds (N=79) of the patients were white, 19 percent (N=22) were black, and 14 percent (N=17) were Latino. As shown in

Table 1, the three ethnic groups did not differ in demographic or clinical characteristics. No relationship was found between ethnicity and either severity or type of depressive symptoms as measured at baseline by the HAM-D (total score and vegetative and cognitive subscales) and the BSI (total score and subscales for depression, anxiety, and somatization).

The rate of attrition, including voluntary withdrawal, AIDS-related hospitalizations, and administrative removals for reasons such as current substance abuse, was greater among Latinos (53 percent) than among blacks (14 percent) and whites (28 percent) (c2=7.3, df=2, p<.05). However, in a direct linear regression model with study completion as the dependent variable, and age, ethnicity, education, and baseline CD4 count and HAM-D score as independent variables, only the baseline HAM-D score (beta=.03; t=2.6, p<.01) was a significant predictor of study completion, accounting for 7 percent of the total variance (F=2, df=6,86, p=.08).

Forty-one percent of the black subjects were randomly assigned to the fluoxetine group, compared with 59 percent of the Latinos and 67 percent of the whites (c2=10.1, df=2, p<.01). Therefore, we assessed the relationship between ethnicity and treatment response in separate analyses for those randomly assigned to the fluoxetine and the placebo groups.

For patients in the fluoxetine group who completed the eight-week clinical trial, 50 percent of blacks (four of eight) were responders at week 8, compared with 84 percent of whites (36 of 43) and 67 percent of Latinos (two of three). Dosages in the week before week 8 did not differ significantly across ethnic groups; nearly all patients received either 20 mg or 40 mg at week 8 (28 percent and 63 percent of patients, respectively). Due to the low number of Latinos, a chi square test was done using data from whites and blacks only. Whites were more likely to respond (c2=4.5, df=1, p<.05). Among completers who were randomly assigned to receive placebo, 80 percent of Latinos (four of five) were responders at week 8, compared with 36 percent of blacks (four of 11) and 43 percent of whites (six of 14).

Fifty-three percent of whites, 50 percent of blacks, and 35 percent of Latinos reported side effects during treatment, a nonsignificant difference. Ethnicity was not associated with the total number of treatment-emergent side effects during the eight-week trial.

Discussion

In this sample of HIV-positive patients with depressive disorders, ethnicity was associated with the likelihood of study completion and treatment response. Latinos were less likely than blacks or whites to complete the eight-week trial. Blacks were more likely than whites to be nonresponders to fluoxetine. Because only three Latinos assigned to the fluoxetine group completed the eight-week trial, we were unable to assess their outcome. Latinos had a significantly higher response rate to placebo than either blacks or whites. This finding may be related to data suggesting that fewer Latinos in the study were experiencing chronic depression—a recurrent episode of major depression or dysthymia—compared with whites and blacks (40 percent versus 71 percent and 63 percent, respectively).

The major limitation of this study was the small sample sizes of ethnic minorities. Although a third of the sample was either black or Latino, analyses involved substantially smaller subgroups. The small size of the groups not only reduces the power to detect relationships involving ethnicity, but suggests the need for caution in interpreting results that were statistically significant. The HIV status of the study participants differentiates them from samples in other studies, although research has shown that people with HIV are similar to medically healthy patients in their response to antidepressants (

9). Replication of the study with larger samples and with study participants from multiple ethnic groups and both genders are needed to clarify the relationship between ethnicity and the acceptability and outcome of antidepressant treatment so that provision of effective treatment to various ethnic populations can be enhanced.

Acknowledgment

This study was partly supported by grant MH5-2037 to Dr. Rabkin from the National Institute of Mental Health.