Rates of smoking are higher among psychiatric patients than in the general population (

1,

2,

3,

4). Reported rates of nicotine dependence for patients in treatment with a psychiatrist range from 40 to 100 percent (

5). About 25 percent of adult Americans smoke, despite the recognition of associated health hazards (

6). Smoking dependence has been attributed to many pharmacological and behavioral processes (

7), including the withdrawal syndrome that some 80 percent of smokers develop when they stop smoking (

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13).

Although avoidance of withdrawal may be a compelling mechanism underlying continued smoking, certain psychiatric patients, such as those with schizophrenia (

14), have difficulty stopping smoking, in part because they smoke to alleviate some of the uncomfortable side effects of psychotropic drugs (

15). Cigarette smoking has been shown to increase the metabolism or clearance of psychotropic drugs (

16,

17,

18,

19,

20), and patients with schizophrenia who smoke may receive higher doses of neuroleptics than nonsmokers (

21,

22,

23).

The abrupt institution of a hospitalwide smoking ban afforded us an opportunity to examine nicotine dependence among psychiatric inpatients. We hypothesized that smokers would experience the same qualitative symptoms of withdrawal as nonpsychiatric populations and that the withdrawal would aggravate and confound their psychiatric symptoms.

Results

We obtained useful data on 60 patients, 44 of whom were current smokers. Fifty-six patients (15 nonsmokers and 41 smokers, or 93 percent of the sample) completed the first two days of data collection. Forty-eight patients (15 nonsmokers and 33 smokers, or 80 percent of the sample) completed all three days. Those who didn't complete all three days were not significantly different from the completers in their FTQ, NWC, or BPRS scores.

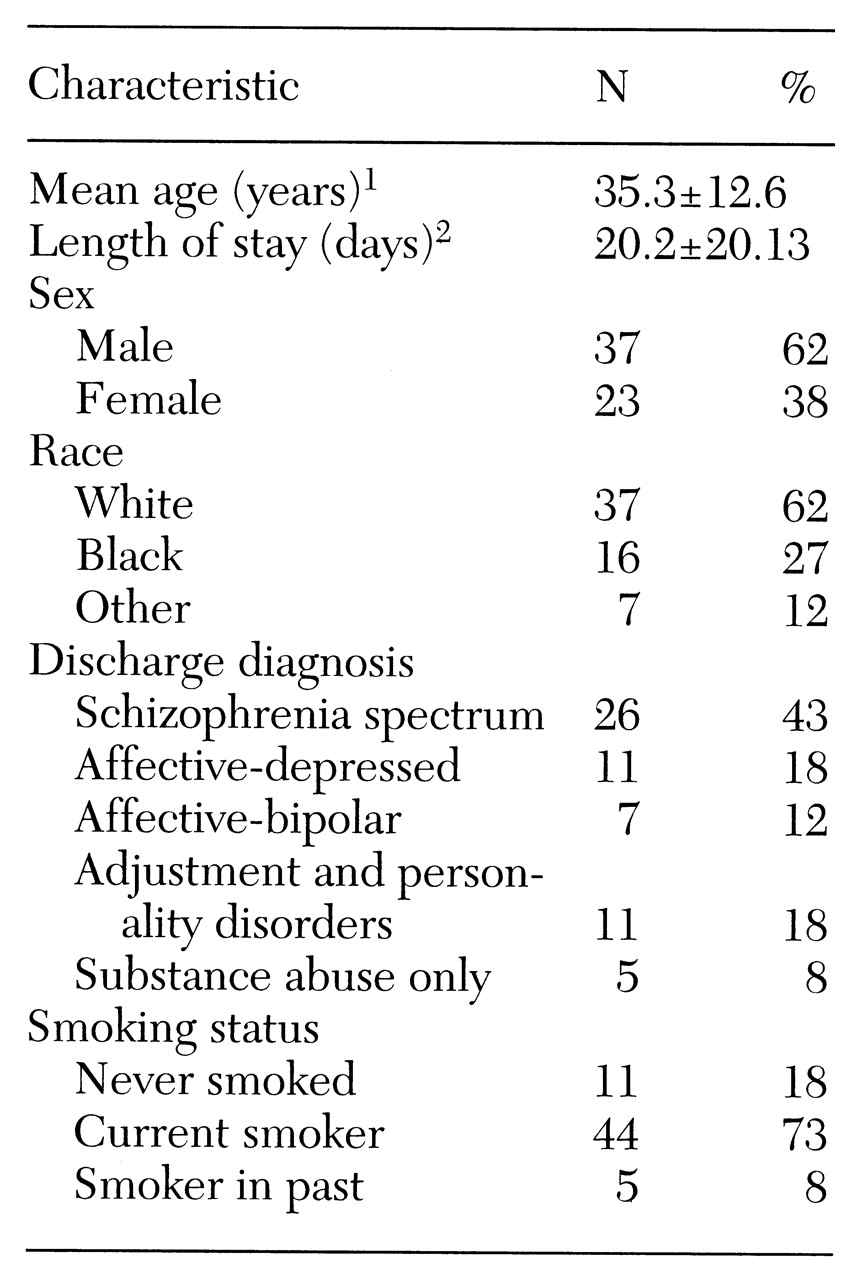

Diagnostic categories for the sample are shown in

Table 1. Of 26 patients with schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, one patient also had an adjustment or personality disorder and one a substance abuse disorder. In the affective-depressed group, three had concurrent substance abuse diagnoses, and one had an adjustment or personality disorder. It is interesting that a much lower proportion of this sample had an alcohol-related disorder compared with the rate of nearly 50 percent we found in a sample of similar patients (

32,

33,

34).

Nearly three-fourths of the subjects were smokers. The prevalence of smoking ranged from 46 to 77 percent in the various diagnostic groups and did not vary significantly between groups. More than three-fourths of those in the schizophrenia-spectrum group and the affective-depressed group were smokers (77 and 82 percent, respectively); in the other groups about half of the patients were smokers.

Males and females did not differ significantly in mean length of hospital stay. The proportion of smokers among males and females was similar (73 and 70 percent, respectively), in contrast to a study by Goff and colleagues (

22) that found a significantly higher rate of smoking among men.

In our study the length of hospital stay for nonsmokers was 28.5 days, nearly twice that of the smokers, which was 17 days (t=1.99, df=58, p=.052).

Ten of the 44 smokers received nicotine gum, nine of whom chose to use it only once or twice. Exclusion of the only patient who chewed the gum on a regular basis did not affect the conclusions of the various statistical analyses. The amounts of gum used were unlikely to have had a detectable effect on withdrawal symptoms (

8).

FTQ scores

FTQ scores, which indicated the degree of nicotine dependence, ranged from 0, among the nonsmokers, to 10. Smokers' FTQ scores ranged from 2 to 10, out of a possible maximum score of 11 (median=6, mean±SD= 6.27±2.13).

BPRS scores

On the first day, the mean±SD BPRS score of nonsmokers (33.8±9.8) was higher than that of smokers (31.8±7.01), although the difference was not statistically significant. On the second and third days, the mean scores of the nonsmokers (32.7±11.6 and 32.9±11.6, respectively) were also higher than those of the smokers (29.4±6.7 and 27.97±6, respectively), but these differences between smokers and nonsmokers were also not significant.

The mean BPRS scores for both groups declined significantly from day 1 to day 2 and from day 1 to day 3, but the decreases were smaller for the nonsmoking group. For the smokers the mean BPRS scores on the second and third days (29.4 and 27.9, respectively) were significantly lower than the score of 31.8 on the first day (paired t=3.01, df=43, p=.004, for the second day; t=4.57, df=31, p<.001, for the third day).

BPRS scores on consecutive days were positively correlated—both from day 1 to day 2 (r=.77, p=.001) and from day 2 to day 3 (r=.54,p=.001)—demonstrating consistency in individual patients' psychopathology over the three days relative to that of other patients.

Among smokers, BPRS scores and the decreases in scores over the three days were not significantly different with respect to diagnosis as measured by a one-way analysis of variance.

On the first day, nonsmokers had appreciably higher scores than smokers on the BPRS items for anxiety and emotional withdrawal, although these differences were not statistically significant. On the other hand, smokers had higher mean scores than nonsmokers on the BPRS items measuring hostility and tension, which were also not significant differences.

Among all patients, the scores on BPRS items that decreased the most from day 1 to day 2 were for anxiety, conceptual disorganization, depressive mood, excitement, hostility, and hallucinations. The decrease in the mean score for the anxiety item was greater for nonsmokers than for smokers (a decrease of .08 versus .14) but the difference was not significant.

Among the nonsmokers, the most marked decreases in the mean scores on individual BPRS items were for anxiety and depressive mood. The most striking difference between smokers and nonsmokers between day 1 and day 2 was on the hostility item; the smokers' mean score decreased by .52 (paired t=1.88, df=43, p=.001), while the nonsmokers' mean score actually increased slightly by .13. In contrast, the smokers' score on the tension item increased from day 1 to day 3, while among nonsmokers it decreased. This difference was not significant. Nevertheless, the increase in tension over the three days and the greater persistence of anxiety among smokers, compared with the decreases on both items among nonsmokers, may have been a reflection of nicotine withdrawal in the smoking group.

NWC scores

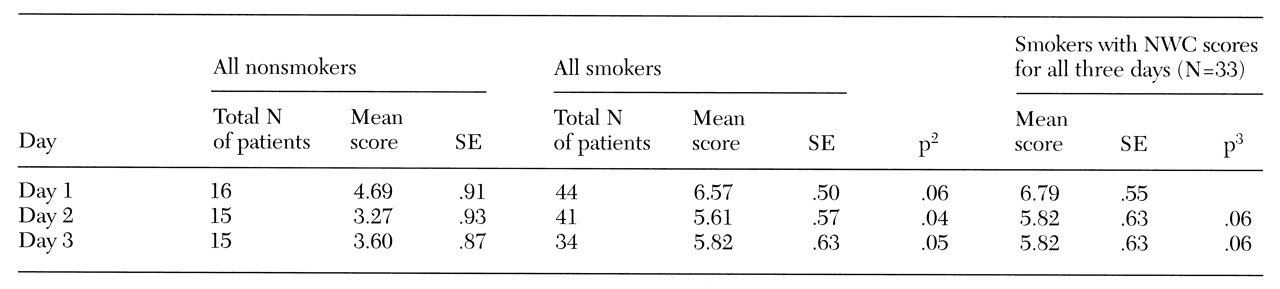

Table 2 presents results for the Nicotine Withdrawal Checklist. Although NWC scores were positively correlated from day 1 to day 2 (r=.78, p=.001) and from day 1 to day 3 (r=.70, p=.001), they declined significantly from day 1 to day 2 and from day 1 to day 3, which reflected decreases in the intensity and number of withdrawal symptoms over the three days.

As anticipated, smokers exhibited more symptoms characteristic of nicotine withdrawal than did nonsmokers (for day 1, mean NWC scores were 6.57 and 4.69, respectively). Decreases in NWC scores over the three days were more marked for the nonsmokers than for the smokers.

Among the individual NWC items, one item—craving for cigarettes—was expected to be different between groups; all but four of the smokers cited it on the first day, while none of the nonsmokers did (χ2=43.6, df=1, p<.001). The NWC items most frequently cited by smokers on the first day were anxiety and tension, cited by 25 smokers (57 percent); restlessness, cited by 24 (55 percent); depression, cited by 22 (50 percent); irritability, cited by 20 (46 percent); and impatience and excessive hunger, cited by 18 each (41 percent). On the second day, the only NWC item cited more frequently by smokers than by nonsmokers was craving (χ2=21.7, df=2, p<.001).

Correlations between scale scores

Reliability analyses showed the BPRS and the NWC scales to be reliable tests. We also examined an extensive matrix of correlations of total scores on the scales and scores on the individual items on each scale, as suggested for this type of study (

35). Most items had only modest to low correlations with other items, suggesting that the majority of them were in fact tapping into different symptoms or dimensions.

Among the few clear associations was the finding that among smokers the FTQ score was significantly correlated with the NWC score (r=.36, p=.01). Among individual items, two NWC items—craving for cigarettes and restlessness—were correlated with the FTQ score (for craving, r=.38, p=.01; for restlessness, r=.36, p=.01). Among the FTQ items, item 6 ("Do you smoke if you are so ill that you stay in bed?") was most highly correlated with the total NWC score. No significant correlations or associations between the FTQ score and changes in the NWC or BPRS over the three days were detected by chi square analysis.

Compared with smokers with schizophrenia and with all other subjects, the eight smokers with depression and the four with bipolar disorder were not more psychiatrically disturbed as measured by the BPRS nor did they suffer greater nicotine withdrawal. These findings are in contrast to those of Glassman and associates (

36). Despite some apparent overlap in the names of items on the BPRS and the NWC, none of the BPRS items were significantly correlated with NWC items.

Discussion and conclusions

A change in hospital policy presented the opportunity to examine the effects of sudden cessation of smoking on symptoms in a population of patients admitted to a psychiatric inpatient unit. We expected to observe a change in psychopathology occasioned by forced alterations in smoking habits. Although nonsmokers had higher BPRS scores, we failed to find statistically significant differences between smokers and nonsmokers in the mean BPRS scores. Scores on the BPRS, which assesses many dimensions of psychopathology, were highest for both smokers and nonsmokers during the first 48 hours after admission and declined significantly thereafter for both groups. These results are consistent with the beneficial effects of hospitalization, benefits that may have exceeded the negative effects of nicotine withdrawal symptoms.

As expected, Nicotine Withdrawal Checklist scores were consistently higher for smokers, and scores decreased for both groups from the first to the second day of observation. No significant correlation was found between psychiatric symptoms as measured by the BPRS and symptoms of nicotine withdrawal. Furthermore, measures of nicotine dependence (the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire), which did correlate with withdrawal symptoms, also failed to show a significant correlation with the BPRS score, indicating the absence of a strong relationship between the degree of dependence on nicotine and patients' psychiatric symptoms, a finding that has been reported previously (

11,

13,

15). Nevertheless, the overlap between symptom complexes of psychiatric illness and nicotine withdrawal poses significant issues for diagnosis and management (

37).

The NWC withdrawal symptoms assessed were the same as those studied by Gritz and associates (

10). Compared with their sample, a higher percentage of our subjects cited each of the various symptoms. However, we found the same items to be the most frequently cited, with the exception of depression—only 16 percent of the subjects in their study cited depression, compared with 50 percent of our subjects.

Our initial concern that nicotine withdrawal would aggravate psychiatric symptoms was not borne out, which has been the experience of other investigators (

24,

25,

26,

28,

38). However, unlike others (

25), we failed to observe any positive effects that could be attributed to the smoking ban. Although our subjects were not in favor of the ban, most became resigned to it, as has been noted in other studies (

38).