In 2004 the American Diabetes Association (ADA) published a consensus statement regarding antipsychotic-related metabolic risk (

1). The statement provided screening recommendations for treated patients, including measurement of fasting plasma glucose at least annually. At approximately the same time, warnings describing hyperglycemia risk associated with second-generation antipsychotic treatment were added to Food and Drug Administration-approved labels. However, low monitoring rates have persisted (

2,

3). This has stimulated interest in strategies to disseminate knowledge of risk and recommended management approaches, which could lower risk of adverse cardiometabolic outcomes and address the low level of screening and prevention in this population.

Literature in this area has largely been limited to uncontrolled case reports. Only one randomized, controlled study evaluated a method to improve the medical care of patients with mental illness (

4). In that study, community mental health center (CMHC) patients were randomly assigned to receive care as usual or combined mental health and general medical care coordinated by a case manager. Patients assigned to the care-coordination model were more likely to receive evidence-based care for cardiometabolic disease and risk factors and improve their Framingham Cardiovascular Risk Index scores. However, the program was labor intensive and expensive, limiting feasibility of use.

A best-practice solution

Quality improvement programs have been implemented to increase the use of best practices among health care providers in multiple specialties, thereby improving health outcomes. Six Sigma is a quality management program originally developed for business and manufacturing processes and subsequently adapted for use in a variety of settings. Quality improvement programs such as Six Sigma are based on the diffusion of innovation theory (or diffusion theory), which broadly describes the process of how new ideas and technologies are communicated through social systems and adopted over time.

Six Sigma methodology was adapted for use in health care settings by adding “lean thinking” concepts (Lean Six Sigma), which aim to optimize quality by minimizing waste and increasing value-added activities. Lean thinking was initially developed to streamline complex manufacturing processes, but it has been successfully applied in health care settings (

5). The combination of lean thinking and Six Sigma processes uses diffusion theory concepts to identify problems and develop innovative strategies for rapid quality improvement. One concept is observability, or the degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others within the social system, a concept considered integral to the early adoption of new practices. This column provides a description of the successful implementation of a best-practice glucose screening intervention in a CMHC setting that used Lean Six Sigma methods based on diffusion theory.

Settings

CMHCs.

In a CMHC network of four outpatient clinics serving approximately 7,300 adult patients, a quality improvement initiative to implement a best-practice fasting glucose screening program was developed using the described quality improvement methods. Medical records personnel, under the supervision of the CMHC medical director, assessed baseline (preintervention, November 2005) plasma glucose annual screening rates at each CMHC site (calculated as the percentage of antipsychotic-treated patients who had at least one measured glucose value over the previous 12 months). Then, in consultation with the medical staff, the CMHC medical director developed a best-practice glucose screening protocol. This included annual fasting glucose screening or, if fasting was not feasible, annual random plasma or finger-stick glucose screening. The medical director set the target monthly average screening rate for glucose testing in the past year at 70% for the first intervention period (2006) and 90% for the second intervention period (2007–2008).

The glucose screening protocol was initiated simultaneously at all four CMHC clinical sites in January 2006. In advance of scheduled visits, the CMHC pharmacy gave medical records staff a list of patients currently treated with an antipsychotic, and medical records staff were instructed to review the medical tests section of the chart for evidence of any glucose value obtained in the prior 12 months. If no documentation of glucose screening in the previous 12 months could be found on chart review, a paper flag with notification of the need to screen was placed in the medical tests section of the chart by medical records staff.

Ongoing reinforcement of the program by the medical director included the following: monthly electronic newsletters featuring information about the glucose screening program, individual screening rates e-mailed to each physician in comparison to the target rate and the rate of all other deidentified staff physicians, and presentation of site-specific average screening rates relative to the other three sites at monthly medical staff meetings. In response to below-target site-specific screening rates, site visits were conducted by the medical director and medical records administrative staff to review screening processes.

Academic outpatient psychiatric clinic.

An outpatient psychiatric training clinic in a nearby academic medical center served as a comparison. This clinic serves approximately 2,000 active adult patients and is staffed full-time by third-year residents who also spend half a day per week at one of the CMHC sites. Resident physicians received initial education about the CMHC's glucose screening program and reminders to screen their CMHC patients before clinic appointments, but they did not participate in the CMHC regular monthly medical meetings and did not receive electronic newsletters about the program. Residents received hard copies of their personal screening rate rank order relative to other deidentified CMHC physicians for their CMHC patients but they did not receive this information for activities performed in the academic clinic.

In December 2007 attending-level faculty with dual supervisory roles at the two CMHC sites and the comparison clinic identified active patients treated in the comparison clinic with antipsychotic agents for at least 12 months and retrospectively searched the electronic medical record for evidence of glucose testing during this time (values obtained during morning hours up to 10 a.m. were included to approximate fasting conditions). [More information about the two settings and the intervention is available in an online supplement at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Program assessment

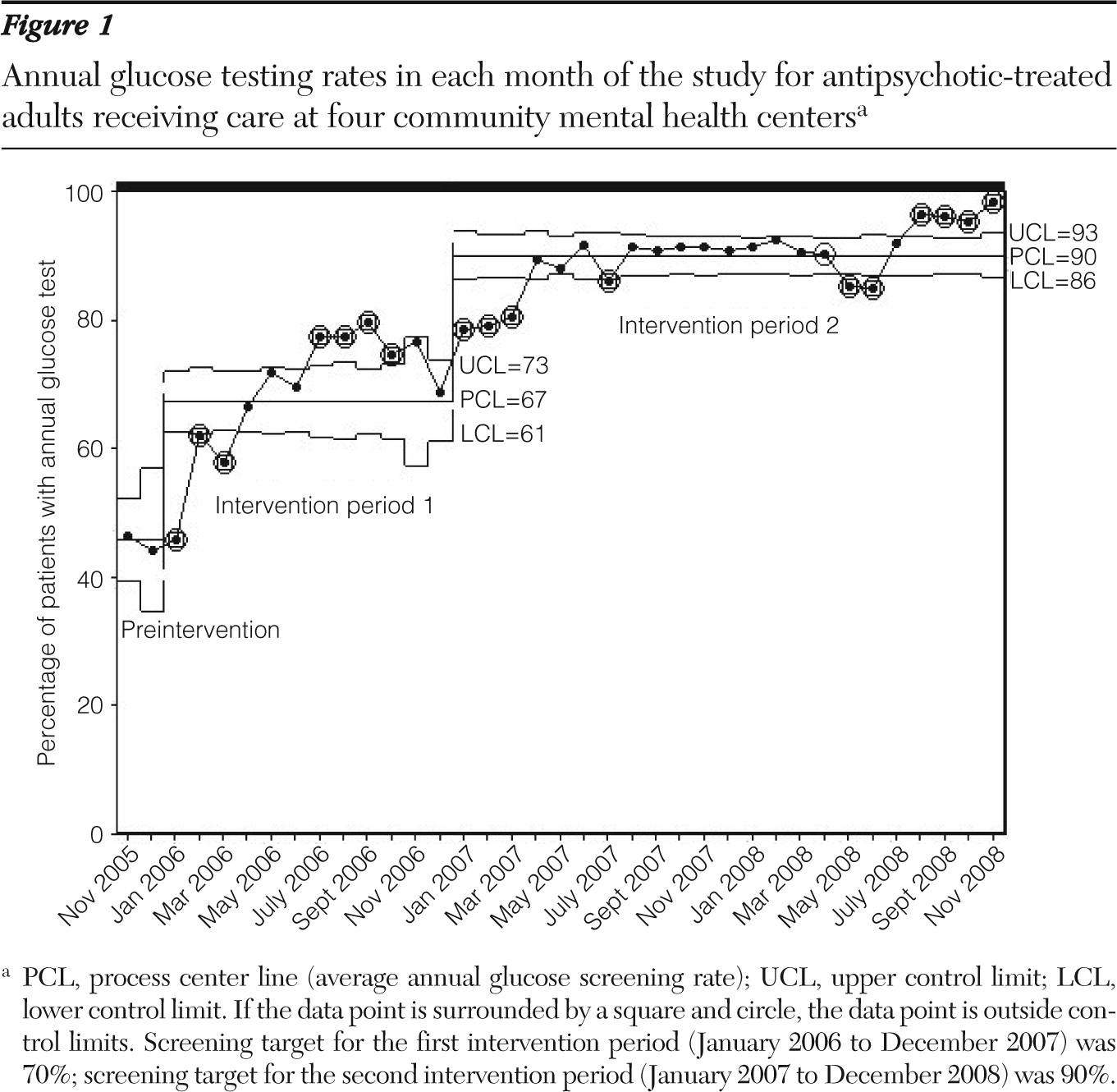

Trends in testing rates were plotted using Microsoft Excel. SPC IV Excel was used to determine the statistical limits associated with the glucose testing rates generated each month. The process center line is the average value for a given time period. For the first intervention period, where the target was 70%, the average screening rate was calculated over the 12 months of 2006; for the second intervention period, where the target screening rate was 90%, average screening rates were calculated over the 12 months of 2007 and 2008, respectively.

Program outcomes

Figure 1 shows the overall annual glucose testing rates in each month of the study for antipsychotic-treated adults receiving care at all four CMHC clinics (November 2005 through November 2008). The baseline (November 2005) average screening rate was 46%, consistent with average national screening rates at the time (

3,

6).

The overall screening rate increased to 67% during the first intervention period (2006); two of the CMHC sites remained below the 70% screening rate target. In response, the medical director and medical records administrative staff conducted site visits in December 2006, concurrently increasing messaging to physicians regarding their screening rates relative to other deidentified staff physicians.

During the second intervention (2007), the overall annual glucose testing rates in each month of the study increased to the target of 90%. However, the same two CMHC sites again did not reach the 90% screening target. Another targeted intervention consisting of a site visit and increased messaging to physicians regarding their individual screening rates in comparison to other deidentified physicians occurred in December 2007. A repeat intervention occurred in April 2008. [An expanded Results section and a figure showing site-specific outcomes are available in the online supplement at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

A one-time assessment of screening rates in the comparison clinic was performed in December 2007. The assessment indicated an overall screening rate of 58%, with glucose screening counted if it was ordered by any physician within the academic medical center. Notably, the screening rate at the comparison clinic was 26%–38% lower than screening rates at all four CMHC clinics during the same month.

Discussion

Although psychiatrists in the comparison academic outpatient psychiatric clinic received the same educational information provided in the CMHC sites, annual glucose testing rates were lower than they were in the CMHC sites, where active client-specific and physician report interventions were in place. In addition, physicians in the comparison clinic did not receive electronic communications that included a rank-order listing of screening rates by physician and did not attend regular monthly medical staff meetings where this information was reviewed. This suggests that a key component underlying observed changes in screening rates may be the physician- and client-specific reminders. Individual physician screening rates presented in comparison to the deidentified screening rates of one's peers emphasized both observability and individual accountability for screening.

This program was subject to several limitations. Screening information was compiled from monthly deidentified data sets that did not differentiate new from existing patients. Additionally, the intervention focused only on plasma glucose screening, rather than on a more complete list of modifiable risk factors targeted by public health guidelines and the 2004 ADA consensus statement (

1). Further study is needed to evaluate individual patient characteristics that may affect screening rates and to determine whether additional complexity in screening requirements is associated with similar success with respect to screening all recommended parameters. [An expanded Discussion section and additional references are available in an online supplement at

ps.psychiatryonline.org.]

Conclusions

These results provide a successful example of a quality improvement approach to increase the level of general medical care for patients treated in CMHC settings and suggest that focus on individual clinician behavior in comparison to peers is an effective tactic to promote best practices.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

Dr. Newcomer has received research grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer. He has served as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Biovail, Obecure, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, H. Lundbeck, Pfizer and Sepracor/Sunovion. He has been a consultant to litigationi regarding medication effects. He has been a member of Data Safety Monitoring Boards for Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma America, Inc., Schering-Plough/MERCK, and Vivus, Inc. He has received royalties from Jones & Bartlett Publishers for a metabolic screening form.