Research suggests that religious beliefs and practices are commonly helpful for people with severe mental illness (

1,

2). Yet spiritual assessments are not a part of regular mental health care and are not well accepted by psychiatrists (

3). There have been no published studies, to our knowledge, that address whether changes in religious faith among adults who are chronically homeless are related to improved functioning.

Most supported housing programs do not adhere to any religious ideology and cannot promote religion through their governmentally funded services. This study examined changes in self-reported religious faith over a one-year period among adults who were chronically homeless and their association with clinical and psychosocial outcomes. We hypothesized that increased religiosity would be associated with better outcomes.

Methods

Data were collected from 2004 to 2009 from 582 clients at 11 sites participating in the Collaborative Initiative to Help End Chronic Homelessness, or CICH (

4). CICH provided adults who were chronically homeless with permanent housing and supportive primary health care and mental health services. None of the providers were faith-based organizations. All participants provided written informed consent, and study procedures were approved by institutional review boards at each site. All measures described below were collected at baseline and one-year follow-up.

Religiosity was assessed by two items, adapted from a previous study (

5), that asked participants to rate on a 4-point scale how important their religious belief or faith had been in their lives and how helpful it had been in dealing with personal problems in the previous three months. Responses are 0, not at all; 1, slightly; 2, somewhat; and 3, extremely. Responses to the two questions were averaged for a total score. An additional item, not included in the total score, asked participants to rate on a 4-point scale how often they attended a service at a church, synagogue, mosque, temple, or other place of worship in the previous three months, from 0 (not at all) to 3 (once a week or more).

Participants reported their nighttime residence every day for the previous three months. Residence was categorized as nights living in one's own place, nights living in an institution, or nights homeless. They were also asked whether they worked for pay or did volunteer work and the average number of hours worked per week of each type in the past month.

The Medical Outcomes Study Short Form-12 (SF-12) (

6), the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) (

7), an observed-psychotic behavior rating scale (

8), and the Addiction Severity Index (ASI) (

9) were used to assess general physical health, mental health, and substance abuse.

General subjective quality of life was assessed with one item from the Lehman Quality of Life Interview (

10), community participation by asking participants about their typical activities during the previous two weeks (

11), and social support by asking participants the number of types of persons (such as brother or sister, parent, clergy, friend, or neighbor) they could have counted on for support in the previous three months (

12).

Participants were split into three groups on the basis of whether their mean religiosity scores increased, decreased, or did not change during their first year in the program. Baseline differences between groups were tested with one-way analyses of variance and chi square tests.

Outcome data were analyzed with analyses of covariance on outcomes, controlling for baseline religiosity scores and baseline values of dependent variables. Post hoc group comparisons were made with Fisher's least significant difference test.

Outcome analyses were repeated using an extreme groups design on a subsample of participants whose mean religiosity score increased or decreased by ≥1.

Results

The mean±SD age of participants was 45.59±8.38; 75% were male, 86% were white or black, 99% were not married, and 29% were veterans. They had 11.78±2.54 years of education, had been homeless for 8.29±6.28 years, and had a baseline religiosity score of 1.81±.91 (possible range 0–3).

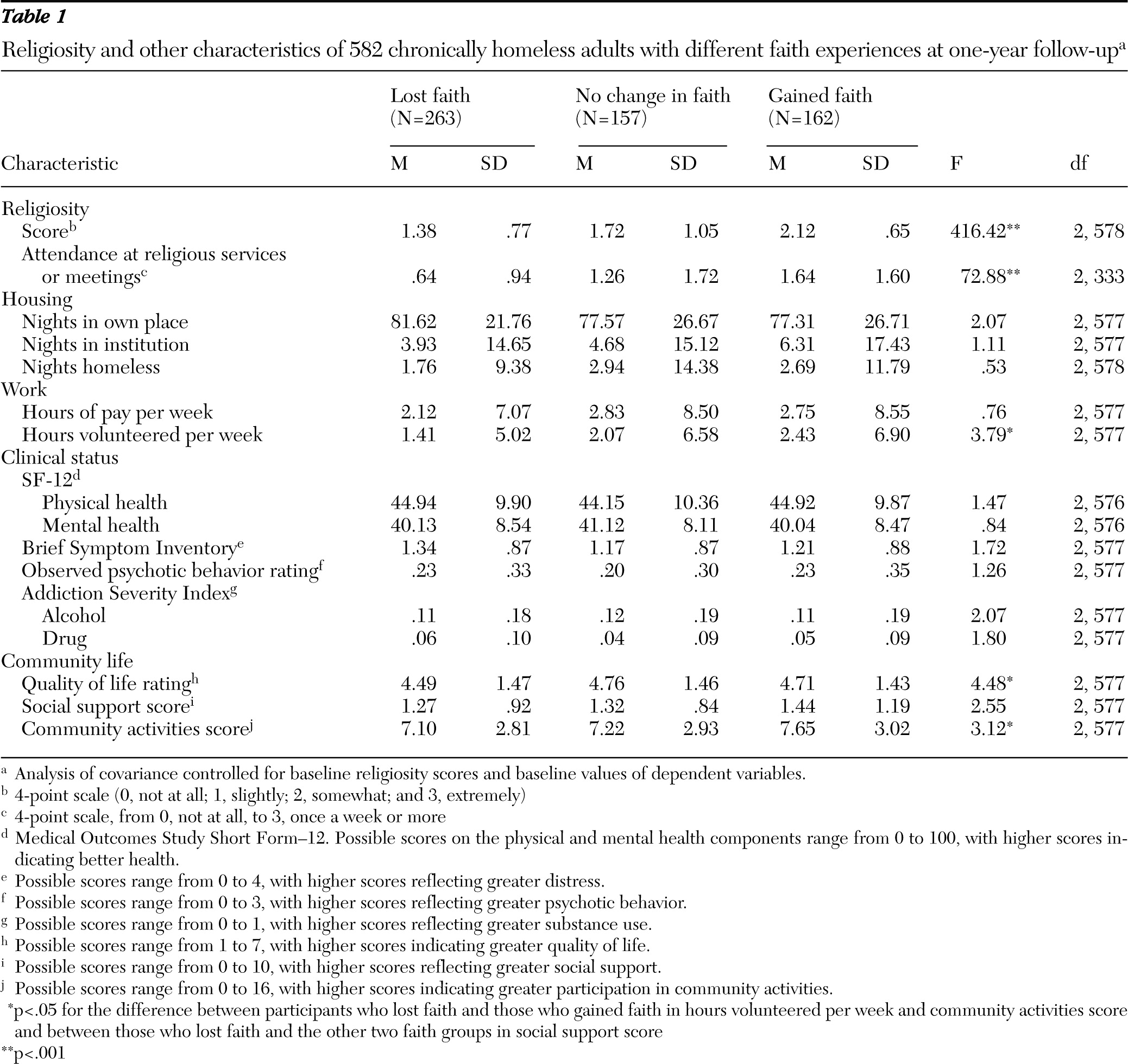

A total of 263 participants were classified as having lost faith, 157 as having had no change in faith, and 162 as having gained faith. There were no significant differences between the groups on any sociodemographic characteristics, homeless history, mental health diagnosis, or measures of housing, work, clinical status, or community life at baseline. One-year follow-up analyses that controlled for baseline religiosity scores and baseline values of dependent variables showed that as expected, the group that gained faith had a significantly higher mean religiosity score than the group that lost faith and reported more frequent attendance at religious services. The group that gained faith also reported doing more volunteer work, having a higher quality of life, and participating in more community activities (

Table 1).

Analyses were repeated for only participants with an increase (N=60) or decrease (N=94) ≥1 in religiosity score. After we controlled for baseline differences and baseline values of dependent variables, participants who had a large gain in faith showed significantly more positive functioning on several outcomes, including higher scores for the SF-12 mental health measure (F=4.01, df=1 and 147, p<.05), lower symptom scores on the BSI (F=7.50, df=1 and 147, p<.01), lower scores on the ASI-Alcohol (F=5.56, df=1 and 147, p<.05), higher score on subjective quality of life (F=18.64, df=1 and 147, p<.001), and greater participation in community activities (F=4.00, df=1 and 147, p<.05) than participants who had a large loss in faith.

Discussion

This study examined religious faith among a sample of adults who had been chronically homeless. A majority of participants rated their religious faith as more than slightly important in their lives and as helpful in dealing with their personal problems. Participants who showed any gain in religious faith during a one-year period did not report greater improvements in clinical symptoms compared with those who lost faith, but they did more volunteer work, engaged in more community activities, and reported a higher quality of life. A subgroup of participants whose faith grew by a relatively large amount reported significant improvements in mental health symptoms compared with participants whose faith was substantially weakened.

These findings were consistent with previous research (

1,

2). Although encouraging religious faith among participants in supported housing programs may be useful, mental health providers may benefit from specific training in this area to address resistance to discussing religiosity with clients (

3) and concerns about infringing on First Amendment rights to the free exercise of religion.

Several limitations deserve comment. Because this study was observational, it is possible that improvements in mental health and psychosocial outcomes led to increases in religious faith, rather than the other way around. However, we speculate that even though none of the providers in CICH were faith based, many adults who are chronically homeless are often exposed to religious encouragement as part of the services and treatment they seek (

13). Finally, although we were concerned about regression to the mean on changes in religiosity scores, we controlled for it by entering baseline religiosity scores and baseline values of dependent variables in all analyses.