Robert Fleury's painting shows Philippe Pinel ordering the shackles removed from the inmates at the Bicêtre Asylum, sparking a revolution in the treatment of people with mental illness. Two hundred years later, the use of seclusion and restraint in psychiatry still raises concerns (

1). Seclusion is considered a therapeutic measure to isolate individuals and limit their contacts with peers; seclusion with restraint involves the additional application of mechanical restraints.

Some professionals defend the use of such practices as a necessary intervention, because studies have shown that 16% of psychiatric inpatients demonstrate aggressive behavior during the first week of hospitalization and that 7% of persons with a mental disorder have perpetrated violence in the year after their diagnosis, compared with 2% in the general population (

2). Aggressive behavior affects the physical and psychological health of psychiatric nursing staff (

3) and leads to increased work absence due to illness and to low morale (

4). After violent incidents, many staff victims remain fearful and report less satisfaction in their work (

5).

The reported incidence of seclusion without restraint in psychiatric settings ranges from 4% to 44% among adults (

6), and use of seclusion with restraints is reported to range from 4% (

7) to 12% (

8). For a variety of reasons, nearly 24% of all patients admitted to a psychiatric emergency department require restraint or a combination of seclusion and restraint (

9). However, many staff members strongly object to the use of these interventions, regarding it as a violation of the patient's right to freedom and dignity (

10). Staff members have reported experiencing shame and have expressed the fear that they are abusing a patient's rights when they must initiate a seclusion or restraint procedure (

11). These interventions also lead patients to develop negative perceptions of the mental health facility, which weakens the therapeutic alliance and negatively affects treatment adherence (

12). In addition, these procedures are associated with negative physical consequences for patients, including lacerations, asphyxiation, and even death (

13). Some patients describe the experience of seclusion and restraint as similar to physical abuse and rape (

14).

Several studies have assessed organizational and staff-level predictors of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient settings, either separately (

16,

18,

19) or in combination (

20–

23). However, to our knowledge, no study has focused on staff members' perception of patient aggression as a predictor of the use of seclusion and restraint while also taking into account other important factors. The goal of this study was to identify the most accurate predictors of the use of seclusion and restraint on psychiatric wards. Use of these interventions has come under scrutiny in psychiatric treatment settings in the past few decades (

24,

25). The study reported here is therefore in line with a variety of initiatives to reduce the use of seclusion and restraint.

Discussion

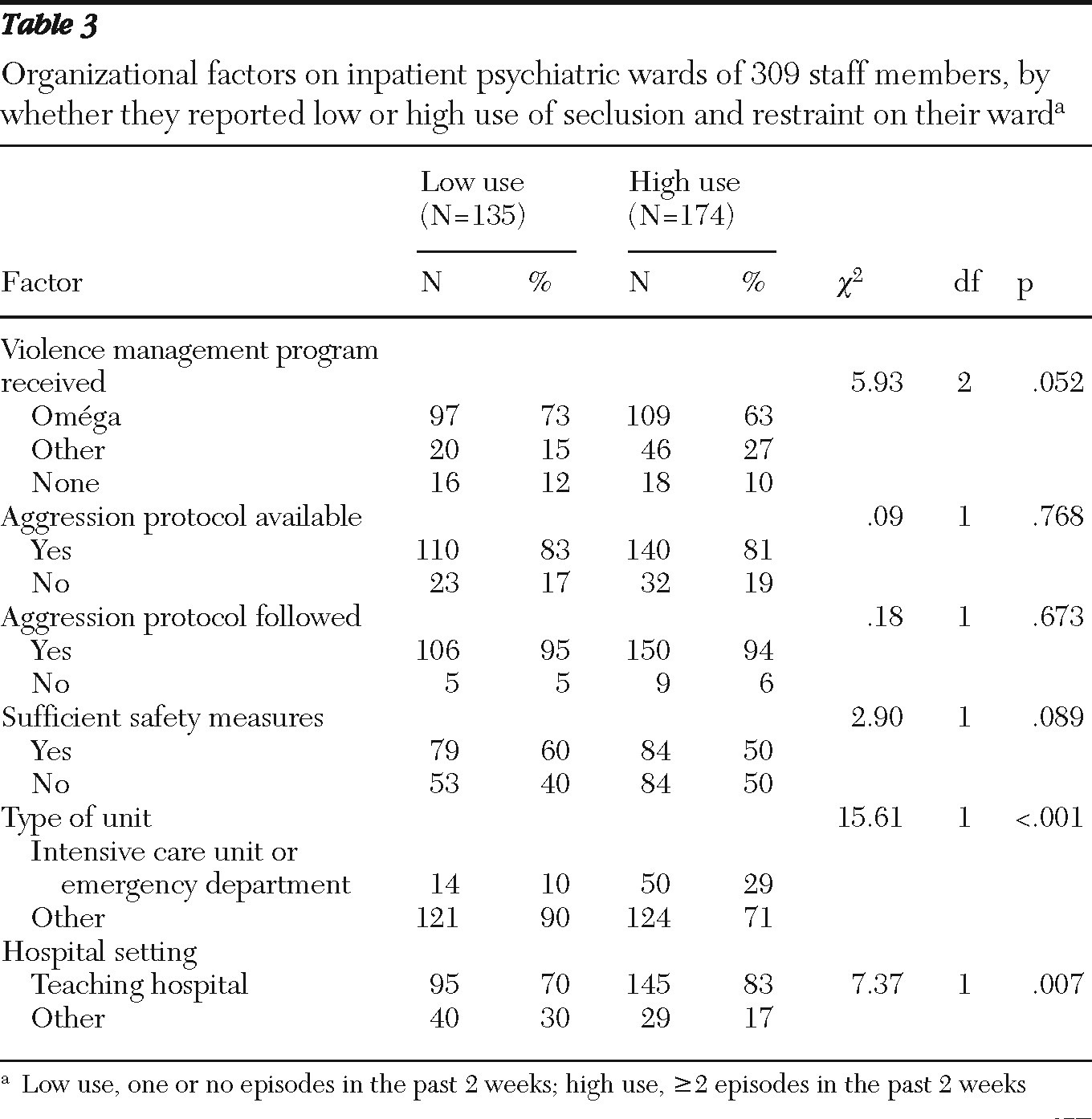

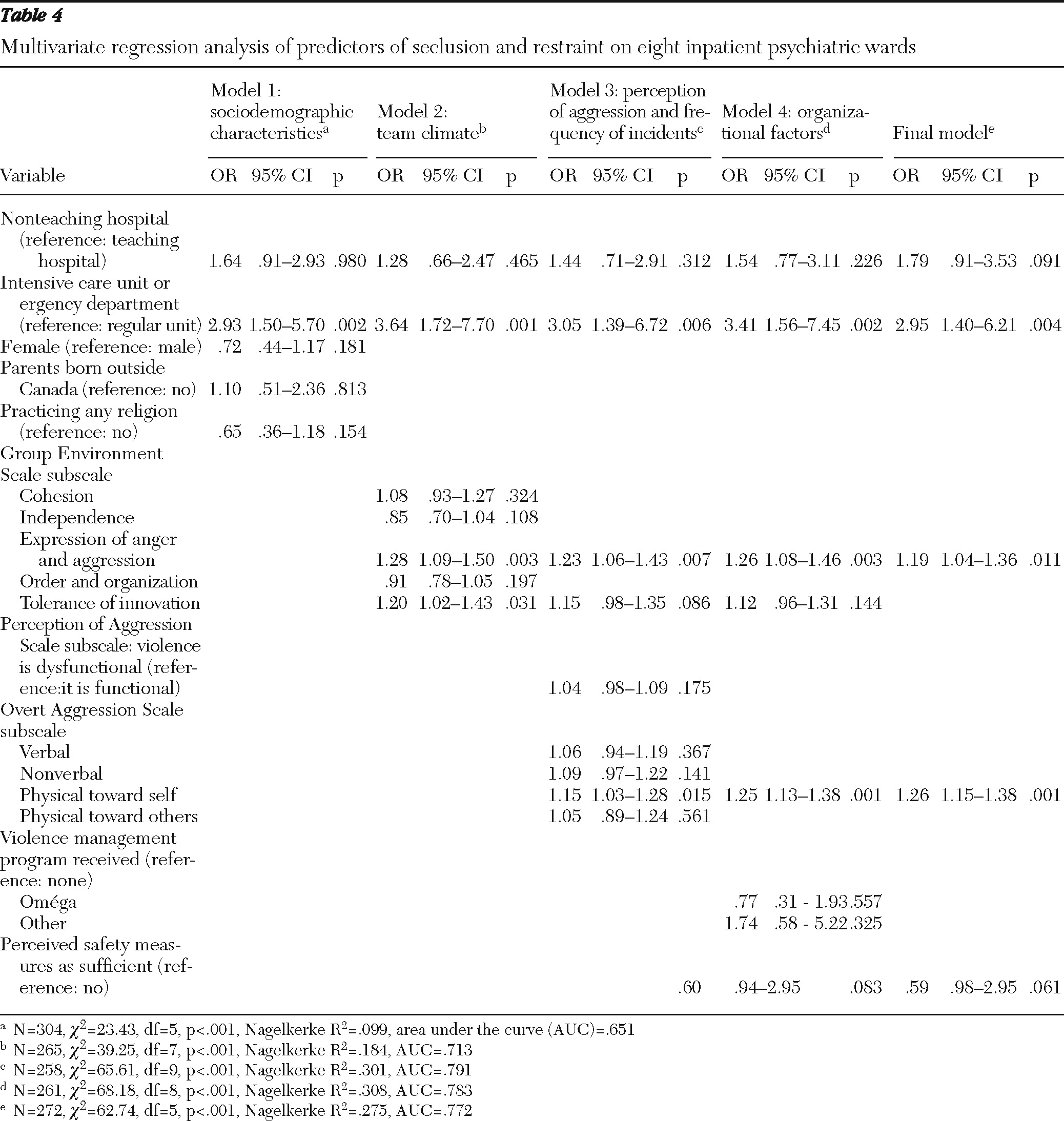

The purpose of this study was to explore staff-related and organizational predictors of the use of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient settings from the perspective of care providers. The study found that use was higher in certain types of hospital settings—intensive care unit and emergency departments—and when staff perceived greater expression of anger and aggression among team members, more incidents of aggression against the self among patients, and insufficient safety measures in the workplace. These findings underscore the importance of evaluating multiple factors (

15), such as violence and safety perceptions, when examining reasons for use of seclusion and restraint.

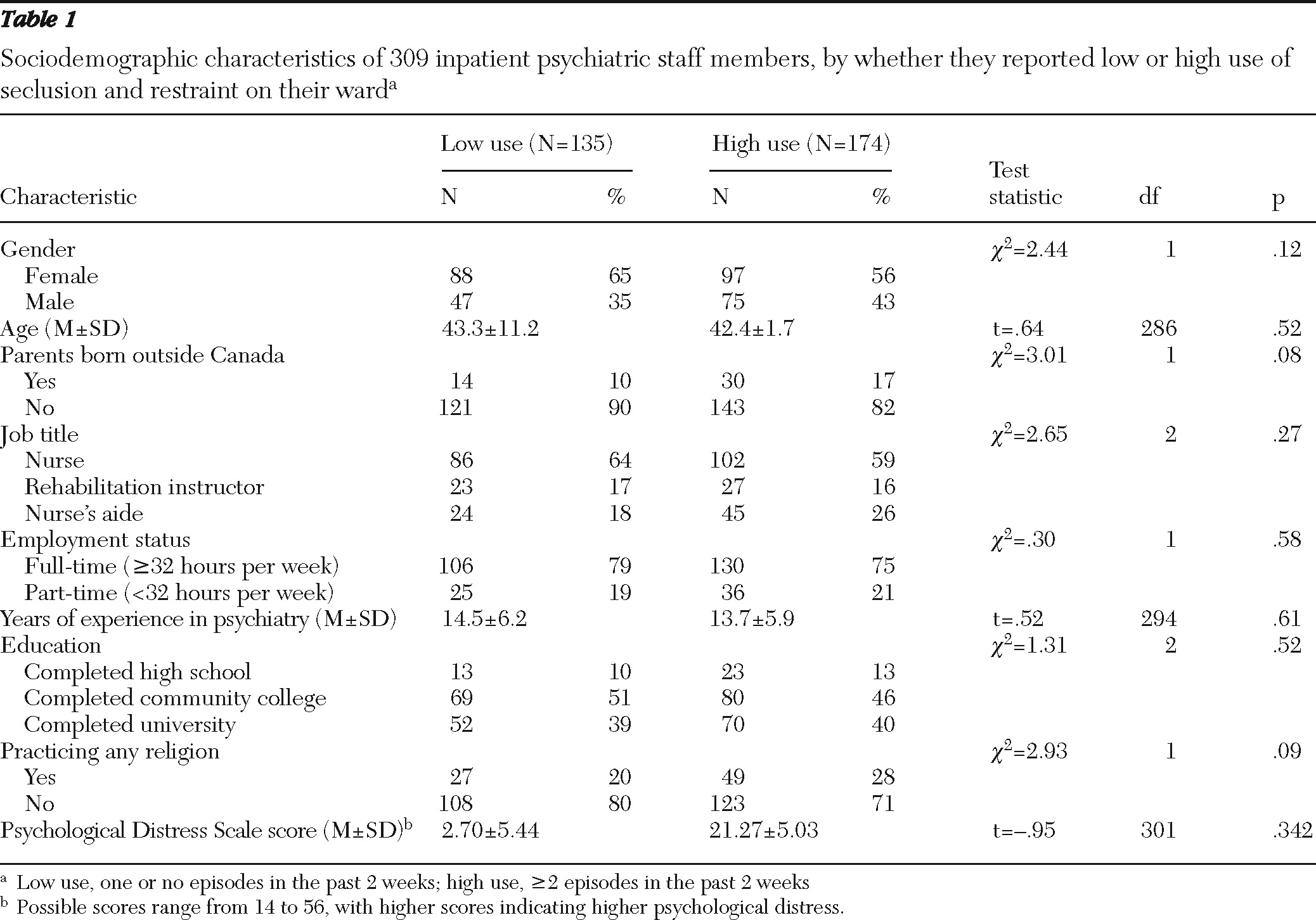

In contrast to previous studies, our study did not find that sociodemographic characteristics of staff were a valid basis for predicting the use of seclusion and restraint. Staff education level, type of work (job title), and gender (

43) have been found to affect the prevalence of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric wards and the incidence of violent behavior in general (

44). Experienced staff members are generally considered to calm patients more effectively than less experienced staff and to report less use of seclusion and restraint (

6,

45). Findings of studies on gender and the likelihood of being the victim of a violent attack (

45) are contradictory, a fact that may explain why our study found no difference in use of seclusion and restraint by gender. Furthermore, whereas other studies found a cultural bias in the use of seclusion and restraint use, our study did not find a difference between those with parents born in Canada or outside Canada.

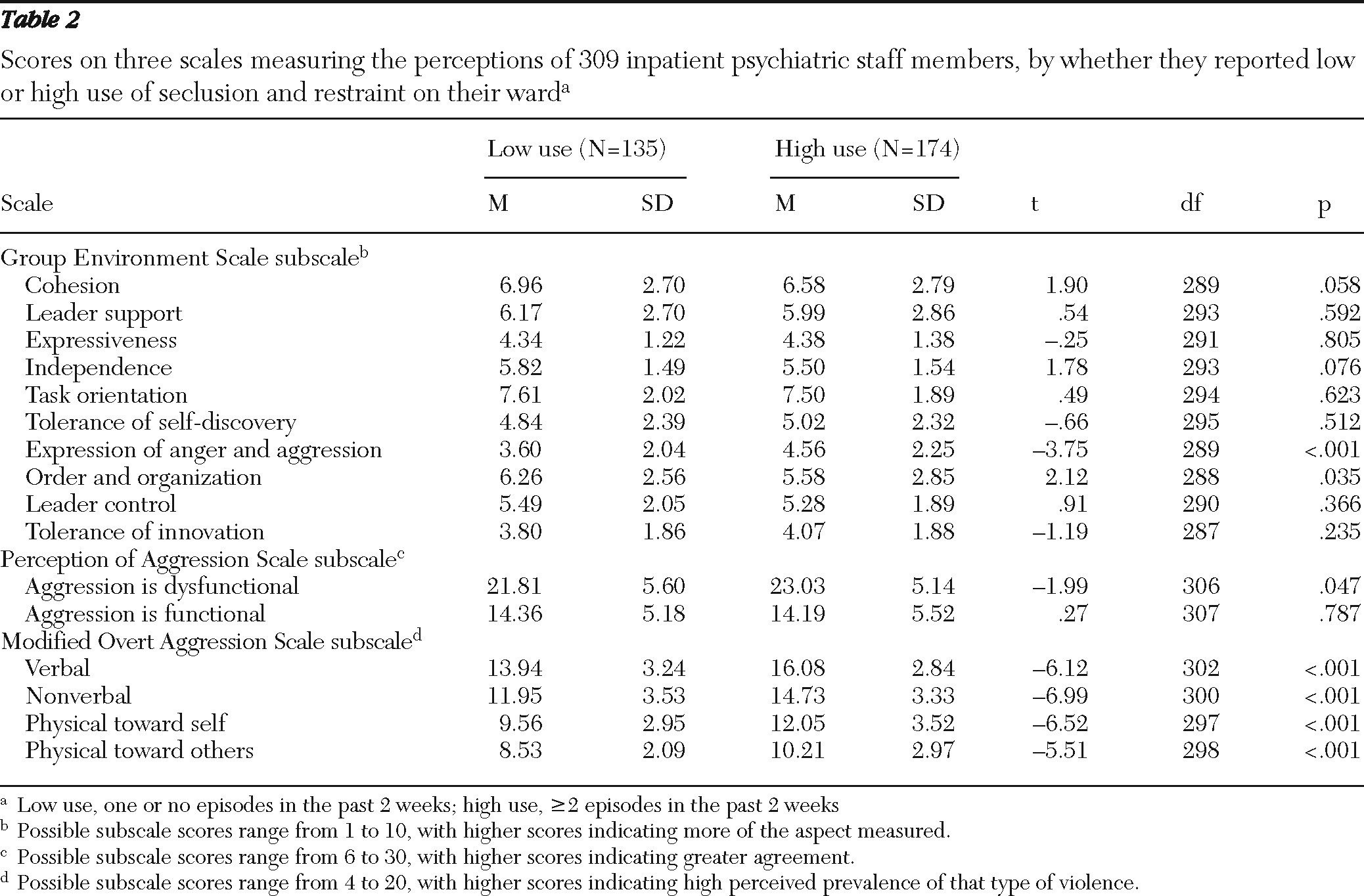

The second multivariate model assessed the importance of team climate in managing seclusion and restraint. Two GES subscales were positively correlated with increased use. The perception of greater expression of anger and aggression among team members was a predictor of seclusion and restraint in the final model. Indeed, it is easy to understand how a psychiatric ward where expression of anger and aggressive behavior among staff members is more common would give rise to greater use of seclusion and restraint. What does this finding tell us about team climate and work satisfaction? Staff members who are more satisfied with their hospital setting and their team climate have been shown to perceive lower rates of aggression among patients (

45), probably because of appropriate management and support by colleagues and administrative personnel when aggressive events occur. Many staff members in psychiatric wards feel socially pressured to “control” patients who have lost their rational capacities (

46), but some staff members who consider seclusion and restraint demeaning to the patient and contrary to the principles of autonomy and care may feel conflicted. Appropriate management of anger and aggression by team members creates a sense of security and can help reconcile the balance between therapeutic interventions and the need to control patients. In the long run, the anxiety of some staff regarding aggressive behavior might be alleviated if aggression is perceived as part of the mental disorder and handled with more tolerance. In summary, these findings underscore previous research suggesting that the prevalence of seclusion and restraint in inpatient psychiatric settings is influenced more by team climate and organizational variables than by individual characteristics.

The scales used to measure perceptions of aggression and the frequency of aggressive incidents shed further light on the management of seclusion and restraint. Scores on a POAS subscale indicated that when violence was perceived as dysfunctional, seclusion and restraint were used more frequently. Scores on the OAS subscales showed that when the analysis controlled for unit type, higher perceived violence of various types (verbal, nonverbal, against self, or against others) predicted greater use of seclusion and restraint in the past two weeks. Taken together, these findings suggest that fears provoked by the irrational aggressiveness of psychiatric patients affect frontline workers in psychiatric wards and the way that they manage seclusion and restraint. As Foster and colleagues (

18) reported, staff were more likely to use physical methods to manage incidents of aggression when they experienced fear, and fear can be induced by working in environments such as psychiatric wards, where incidents of physical and verbal abuse occur often and where it is difficult to understand the causes of patient aggression. In addition, Bowers and colleagues (

47) reported that care providers with a positive attitude toward people with mental health problems had an easier time managing their emotional reactions and adopting a cooperative attitude with clients. Care providers with a negative attitude managed their emotional reactions less skillfully. They consequently adopted a controlling attitude that led them to resort more readily to use of seclusion and restraint. Wards with higher aggression rates have been found to have a preponderance of nurses whose style of interacting and intervening is restrictive and controlling (

48).

However, only the OAS subscale measuring perceptions of violence against the self was a significant predictor in our final model. Recent empirical studies do not provide a reason for this finding—that is, they do not explain why this subscale rather than the OAS subscales measuring other types of violence was a predictor of seclusion and restraint use. On psychiatric wards, self-harm has been found to be a precipitating factor of the use of these interventions (

6,

9), especially with patients who have affective disorders. In such circumstances, seclusion and restraint measures may be perceived as a way of protecting the patient, and psychiatric staff may be more likely to use coercive measures in this context.

Staff training has also been shown to have an impact on the use of seclusion and restraint (

49). Many reports have described examples of violence management training programs that have been implemented in hospitals with the aim of reducing the use of these interventions; many such programs have been successful (

50,

51). In our study, the association between training programs and lower use of seclusion and restraint was significant in the bivariate analysis, but training was not a predictor in the third multivariate model. Systematic training of every staff member might reduce recourse to seclusion and restraint, but current programs need improvement to attain this goal, and more alternatives to these interventions must be developed.

Staff perceptions that safety measures in psychiatric units are insufficient also appears to be important. A trend in the final model suggested that this factor has an independent significant impact on use of seclusion and restraint. This finding is consistent with results of earlier studies showing that psychiatric nurses' decisions were influenced by safety issues in the workplace (

52,

53) and that safety in the working environment was strongly related to staff satisfaction (

54). To reduce the use of seclusion and restraint, staff perceptions of security should be targeted.

The study had several limitations worth noting. First, it was a cross-sectional study with a relatively small sample, although it was conducted in different types of institutions to ensure representation of diverse practices. Second, no data were available for staff members who refused to participate, and nonparticipants may not have had similar profiles. There was also a risk of recall bias in reports of the frequency of seclusion and restraint use. Finally, incidents of seclusion and restraint may have been underreported because of social desirability bias.