Mental illness causes significant impairment for 3% to 18% of youths (

1). However, community-based studies have shown that many children with impairing mental illnesses receive no services or receive only services in the educational system (

2,

3). When youths interact with multiple service sectors, these sectors frequently do not work together to form a comprehensive treatment approach, and services are often inadequate to address symptoms and impairment (

4,

5). In addition, factors unrelated to need, such as age, race, and insurance, drive utilization (

6–

9).

Little information exists about use of mental health services by children with specific diagnoses. Findings suggest that having a disruptive disorder is significantly associated with children's use of mental health services but that having a depressive disorder is not (

6,

10). Few studies have investigated service use among children diagnosed as having serious disorders such as bipolar disorder and psychosis. An examination of MEDSTAT's MarketScan data from 1993 to 1996 for all users of mental health services 17 years of age and younger found that receipt of mental health services fell from 4% to 3% (

11). The frequency of specific diagnoses differed by service setting. Major depression and bipolar disorder, other mental disorders, and mild or moderate depression were most common in inpatient settings, and hyperactivity, other mental disorders, and adjustment reaction disorder were most common in outpatient settings. An analysis of MarketScan data from 1997 to 2000 showed that the overall distribution of diagnoses among youths changed little for hyperactivity, depressive disorders, adjustment disorders, and other disorders but that the prevalence of bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, and anxiety disorders significantly increased (

12). MarketScan data are limited to privately insured youths and lack information on quality, outcomes, satisfaction, and other care settings.

Bipolar disorder is associated with disproportionately greater use of health services and with higher costs, which are driven by more use of inpatient hospitalization (

13). A study of individuals with 1996 insurance claims found that nearly half (40%) of the adolescents who had a diagnosis of bipolar disorder had at least one inpatient hospitalization in that year and that half of this group had more than one (

14). In that study, nearly 25% of youths under age 21 had more than 20 outpatient visits; among the hospitalized youths, almost 50% had more than 30 inpatient days. In the Course and Outcome of Bipolar Illness in Youth study, about 80% of youths with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder used services over a six-month period—67% used outpatient services, 22% used inpatient or partial hospitalization services, and 12% used residential or therapeutic school-based services. Predictors of high levels of care included older age, female sex, greater symptom severity, and rapid cycling. Predictors of more restrictive treatment settings included suicidal and self-injurious behavior, comorbid conduct disorder, and parental substance use disorders (

7).

These studies suggest that mental health service utilization patterns differ in important ways by diagnosis and that specific attention must be focused on the most severe and impairing disorders not only because of the paucity of information but also because these youths use the majority of services, particularly costly services such as hospitalization (

13,

14).

The purpose of this study was to describe service utilization by demographic characteristics and diagnoses for a cohort of children with emotional and behavioral disorders who were first-time users of participating outpatient mental health clinics in four Midwest cities. The study contributes to the scant literature on children's mental health service utilization by focusing on service use by a specific outpatient clinic population, examining various types of services, and exploring patterns of service utilization by diagnosis. We tested the hypothesis that certain demographic characteristics (male sex, older age, white race, and private insurance coverage) and clinical characteristics (major mental illness, a comorbid mental disorder diagnosis, and greater impairment) would be related to utilization of more services and services of greater intensity.

Methods

Sample

The source population consisted of all children between the ages of six and 12 years 11 months who were making a first visit to child outpatient clinics associated with the four university partners in the Longitudinal Assessment of Manic Symptoms (LAMS) study. Parents or guardians accompanying eligible children were approached by researchers using procedures approved by the institutional review board at each university or hospital. Recruitment occurred between December 13, 2005, and December 18, 2008.

After providing consent to participate, adults were asked to complete the ten-item Parent-Completed General Behavior Inventory Mania Form (PGBI-10M) and to answer questions about sociodemographic characteristics (

15). Of 3,329 families who were approached at the participating clinics, 2,622 (79%) agreed to screening. Nearly half (N=1,124, 43%) scored above the a priori cutoff of 12 on the PGBI-10M, indicating that the child had elevated symptoms of mania. Of the 1,124 children, 1,111 were eligible for the longitudinal follow-up portion of the study; 13 were ineligible because the parent reported a diagnosis of autism and an IQ of less than 70). Of the 1,111 eligible children with elevated symptoms of mania, 621 parent-child dyads (56%) agreed to participate.

The total sample consisted of an additional 86 children who did not have elevated symptoms of mania. For every ten children with such symptoms, one child without such symptoms was selected as a potential comparator. Minimization methods were used to select the comparator children to match the “modal” child positive for elevated symptoms of mania in the time segment (

16). A total of 86 parent-child dyads in which the child was negative for elevated symptoms of mania agreed to participate. Information on the study design, sample selection, and children's sociodemographic characteristics has been previously reported (

17). Families who agreed to participate in the longitudinal portion of the study were scheduled for a baseline interview, which has been described elsewhere (

18).

Measures

Demographic characteristics.

Demographic characteristics, including child age, sex, race, ethnicity, and insurance status, were collected along with information about the family, such as family composition, socioeconomic status, and parents' education and employment.

Psychiatric disorders.

To assess for current and past psychiatric disorders, children and their parents or guardians were administered the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Episode (

19), supplemented with additional mood onset and offset items from the Washington University in St. Louis Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (

20).

DSM-IV items screening for pervasive developmental disorders were also included.

Diagnoses were grouped into hierarchical categories: bipolar disorder, depressive disorder, psychotic disorder, anxiety disorder, disruptive behavior disorders, pervasive developmental disorders, other, and no diagnosis. The hierarchical order was designed to provide clarity about the status and the evolution of the disorder on the mood spectrum, which is the main area of investigation in the LAMS study. In these analyses, children with comorbid disorders were counted only in the highest diagnostic category. For example, a child with bipolar and anxiety disorder was included only in the bipolar disorder category. Regardless of classification in the hierarchy, all diagnoses were taken into account in the investigation of the impact of comorbidity.

Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS).

The CGAS documents children's overall level of functioning at home, at school, and with peers (

21). Scores range from 1 to 100, with lower scores indicating more impairment. Interviewers completed ratings for the child's current functioning (past two weeks) and for the most severe past episode of psychiatric illness. Children were divided into two impairment groups; those with a CGAS score <51 (indicative of major impairment) and those with CGAS scores ≥51 (mild impairment). The mean±SD scores were 44.26±.34 in the group with major impairment and 60.99±.32 in the group with mild impairment.

Services Assessment of Children and Adolescents (SACA).

The parent version of the SACA gathers information about the child's use of various mental health services in three broad domains: inpatient, outpatient, and school. The SACA was used at the baseline assessment to collect information on lifetime and current service utilization from parent self-report (

22).

Analyses

Descriptive statistics, including means and percentages, are reported to describe the demographic, clinical, and service variables. Chi square analyses evaluated associations among categorical variables (Fisher's exact test was used when cells showed low expected frequencies). Logistic regression analyses evaluated the relationships of demographic characteristics to lifetime or past-year hospitalization and current or lifetime use of specific treatments at baseline.

Results

Sample characteristics

A more detailed description of the sample is available elsewhere (

17,

18). Briefly, approximately two-thirds of the 707 children were male (N=478, 68%) and white (N=455, 64%). Nearly half (N=323, 46%) were between the ages of six and eight. A total of 370 children (52%) were insured solely through Medicaid.

Primary diagnoses in the sample were bipolar disorder (N=162, 23%), depressive disorder (N=124, 18%), psychotic disorder (N=10, 1%), anxiety disorders (N=43, 6%), disruptive behavioral disorders (N=212, 30%), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (N=91, 13%), and pervasive developmental disorders (N=28, 4%). A total of 433 children (61%) had mild functional impairment, and 435 (62%) had taken psychotropic medications during their lifetime.

Service utilization

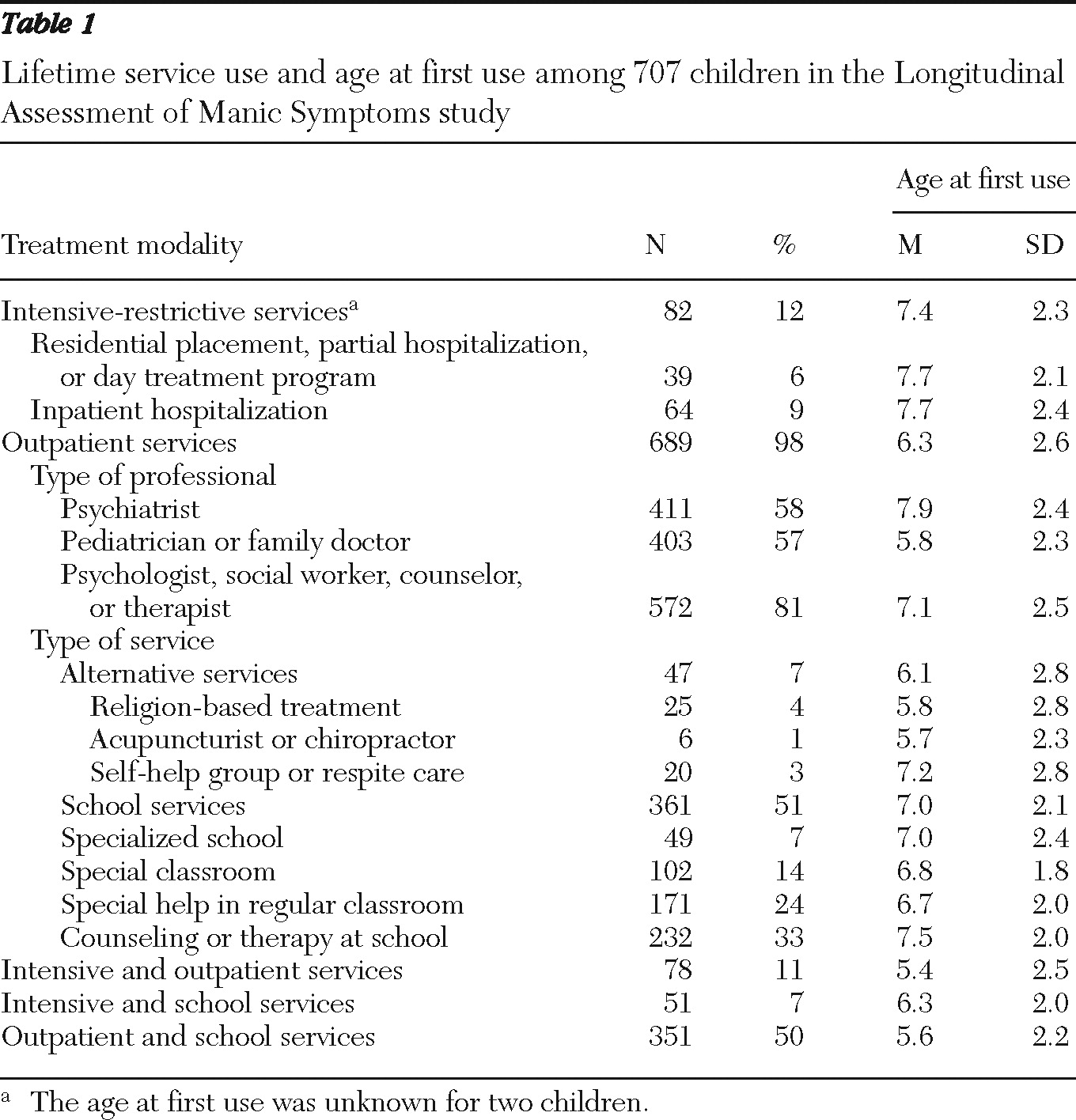

Table 1 presents data on lifetime use of services. Twelve percent of the sample reported use of intensive-restrictive services, most commonly inpatient hospitalization (9%). Ninety-eight percent had used outpatient services, and 58% had consulted with a psychiatrist. School services, which were used by 51% of the sample, most often consisted of special help in the regular classroom (24%) or counseling (33%). Half the sample (50%) had received both outpatient and school mental health services in their lifetime. The mean ages at which children began use of services were 6.3 years for outpatient services, 6.1 for alternative services, 7.4 for intensive-restrictive services, and 7.0 for school services.

Demographic and clinical variables and service use

Bivariate analyses are shown in

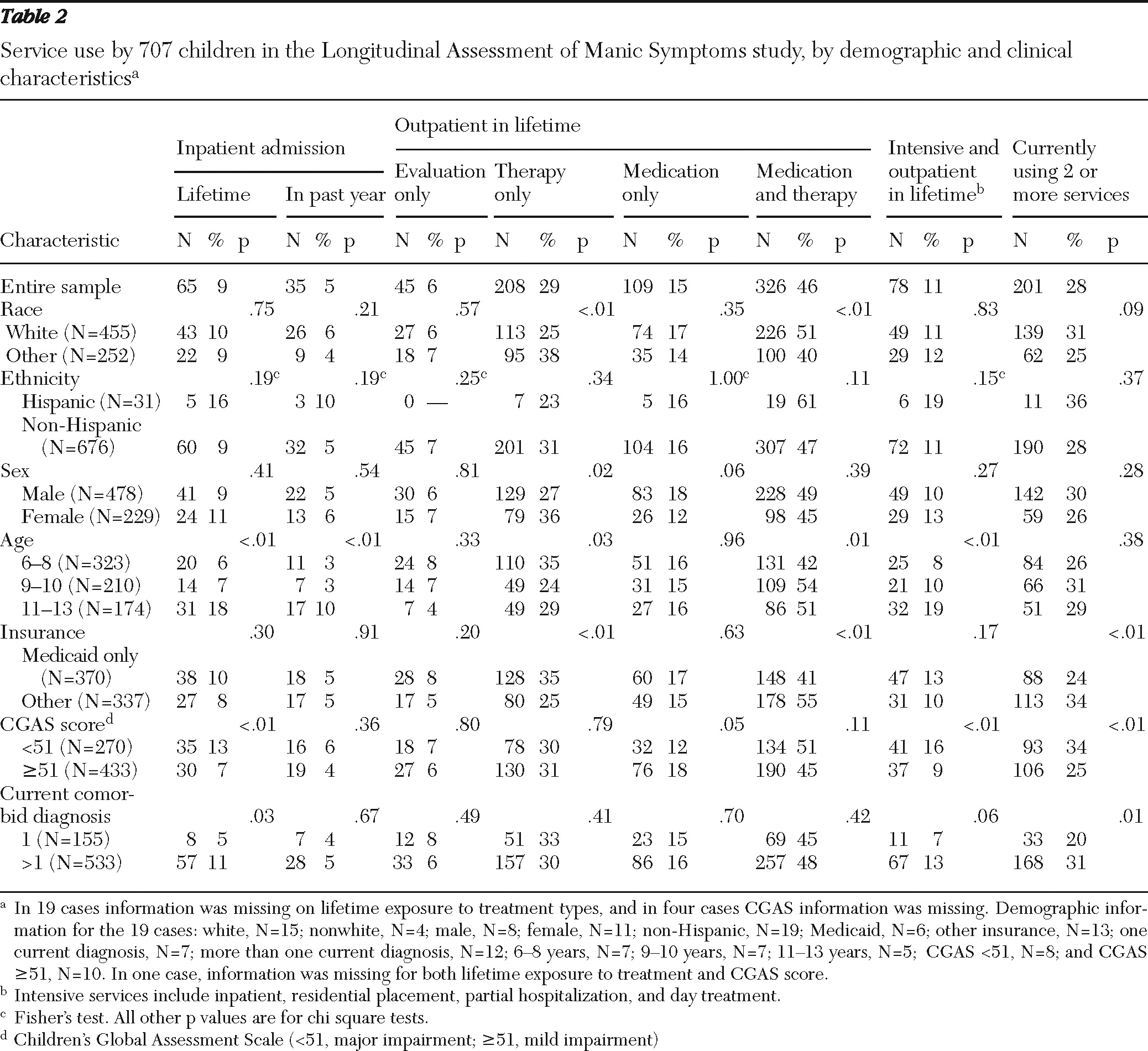

Table 2. Youths who were older (aged 11 to 13), who had lower CGAS scores (greater impairment), and who had more than one current diagnosis were more likely to have had a lifetime hospitalization. In addition, the older youths were significantly more likely to have had a hospital admission in the past year. A greater proportion of the older youths had utilized both intensive (inpatient) and outpatient services during their lifetime (19%) compared with youths aged six to eight (8%) and youths aged nine and ten (10%).

In regard to outpatient services, youths were significantly more likely to have had only therapy in their lifetime if they were nonwhite, female, younger (aged six to eight), and insured by Medicaid (

Table 2). Youths were more likely to report lifetime use of only medication if they had a CGAS score at baseline that indicated mild impairment. White children were significantly more likely than those from other races to have received both medication and therapy during their lifetime, as were older children and children with insurance other than Medicaid. Children insured through Medicaid were significantly less likely than those with other insurance to be currently using two or more services.

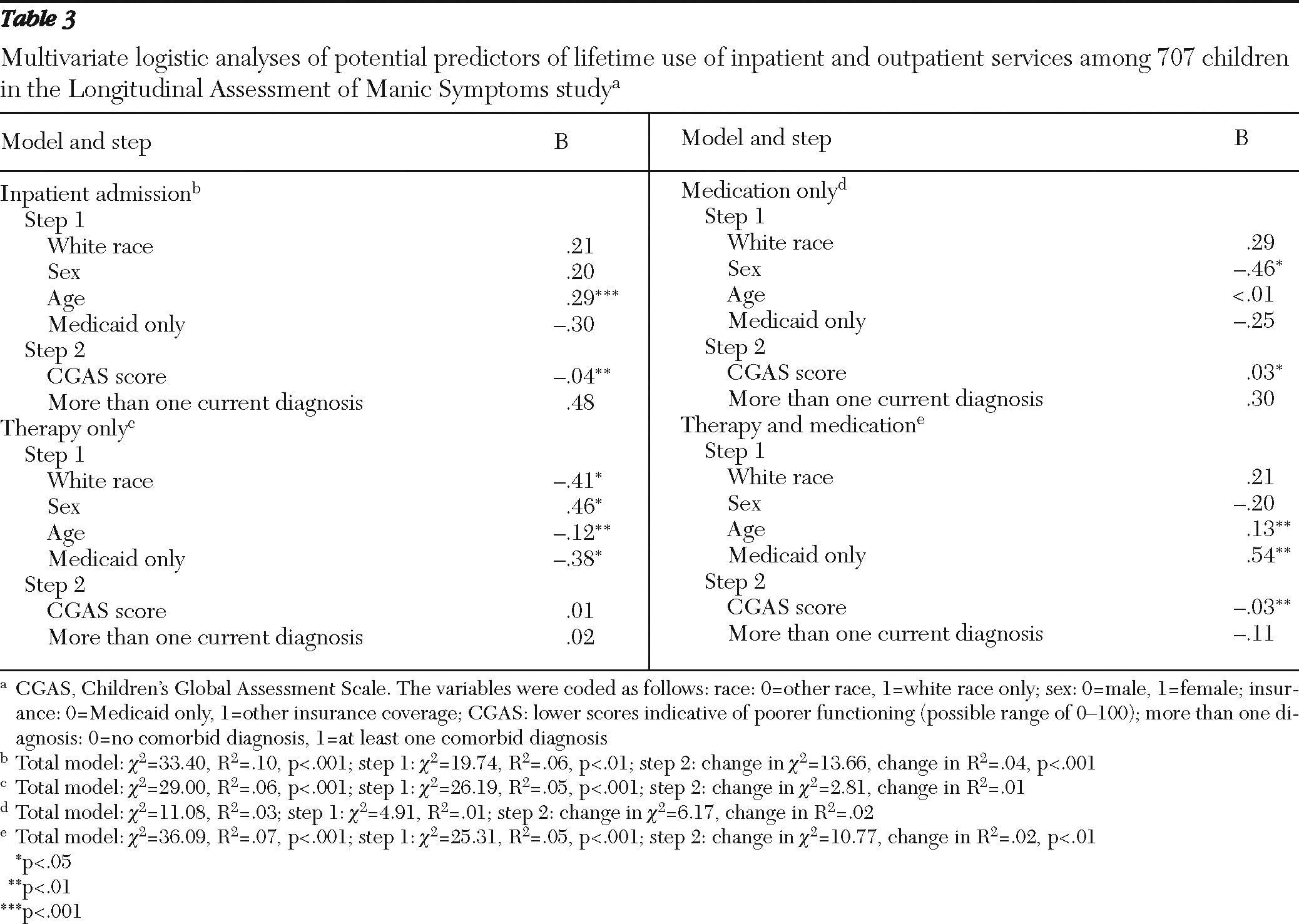

Table 3 presents results from multivariate analyses. When analyses controlled for other demographic and clinical variables, older children with lower CGAS scores were more likely to have ever been hospitalized, consistent with the bivariate results. Receipt of therapy only was significantly associated with being nonwhite, female, younger, and insured by Medicaid. Receipt of medication only was significantly associated with having a higher CGAS score. Lifetime use of both medication and therapy was significantly associated with being older, having insurance other than Medicaid, and having a lower CGAS score.

Association of diagnosis and impairment with service use

As shown in

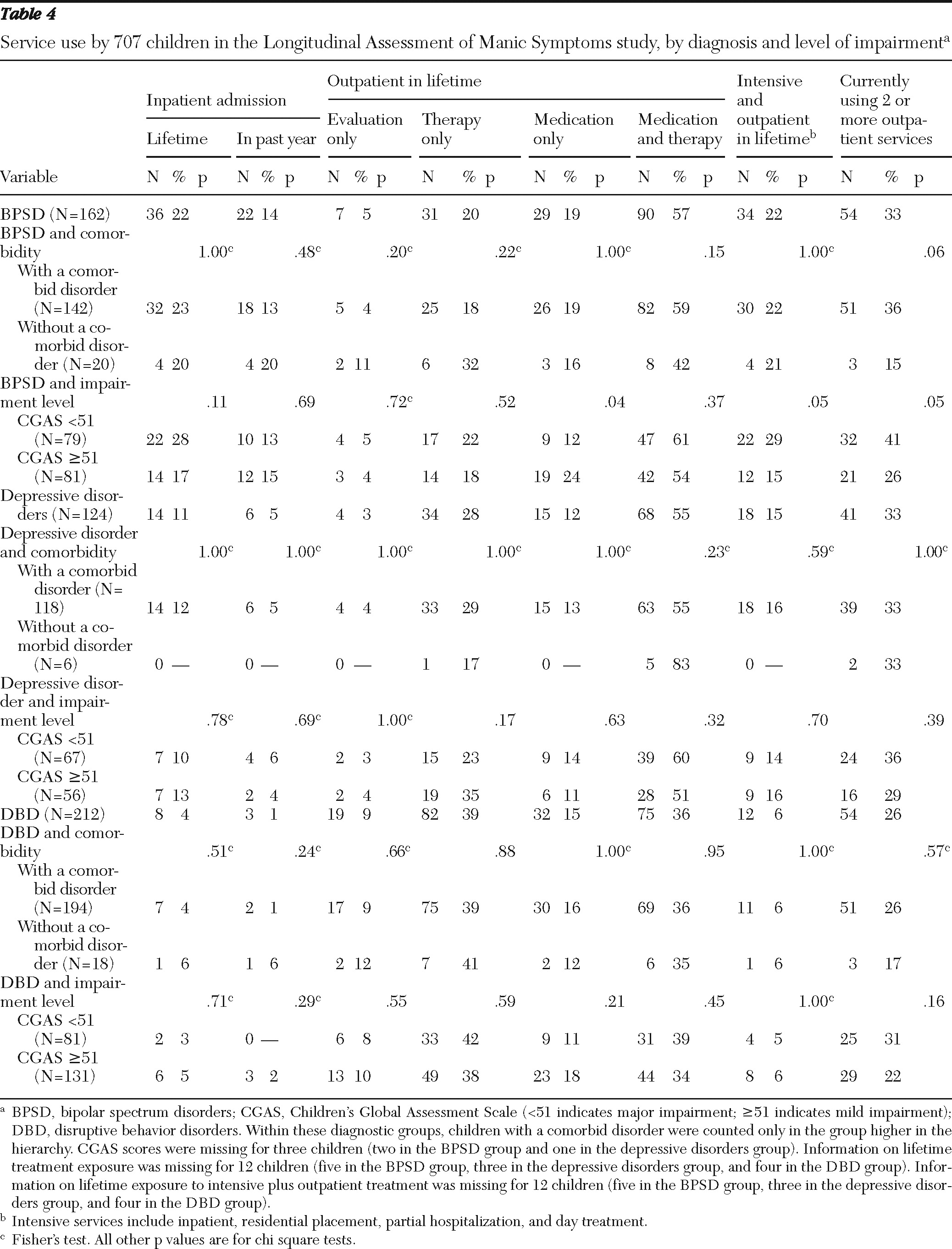

Table 4, children with a diagnosis of bipolar spectrum disorder had significantly higher rates of lifetime inpatient admissions (22%) and admissions in the past year (14%) than children with a depressive disorder (11% and 5%, respectively) and a disruptive behavior disorder (4% and 1%, respectively) (data not shown). However, neither the presence of comorbidity nor current level of functioning were related to lifetime or past-year inpatient admissions.

More than half the youths in both the bipolar spectrum group and the depressive disorder group had received both medication and therapy during their lifetime (bipolar spectrum group, 57%; depressive disorders group, 56%). However, among children in the disruptive behavior disorders group, the proportion of children who had received therapy only (39%) was larger than the proportion who had received both medication and therapy (36%). The proportions of children who had received therapy only were significantly different across the diagnostic categories (p<.001). The presence of a comorbid disorder and impairment did not have an impact on lifetime exposure to various outpatient treatments with one exception. In the bipolar spectrum group, children with higher CGAS scores (mild impairment) were more likely than those with lower scores (major impairment) to have received only medication (24% and 12%, respectively); children with major impairment were more likely than those with mild impairment to be currently utilizing at least two services (41% and 26%) and to report lifetime use of intensive and outpatient services (29% and 15%).

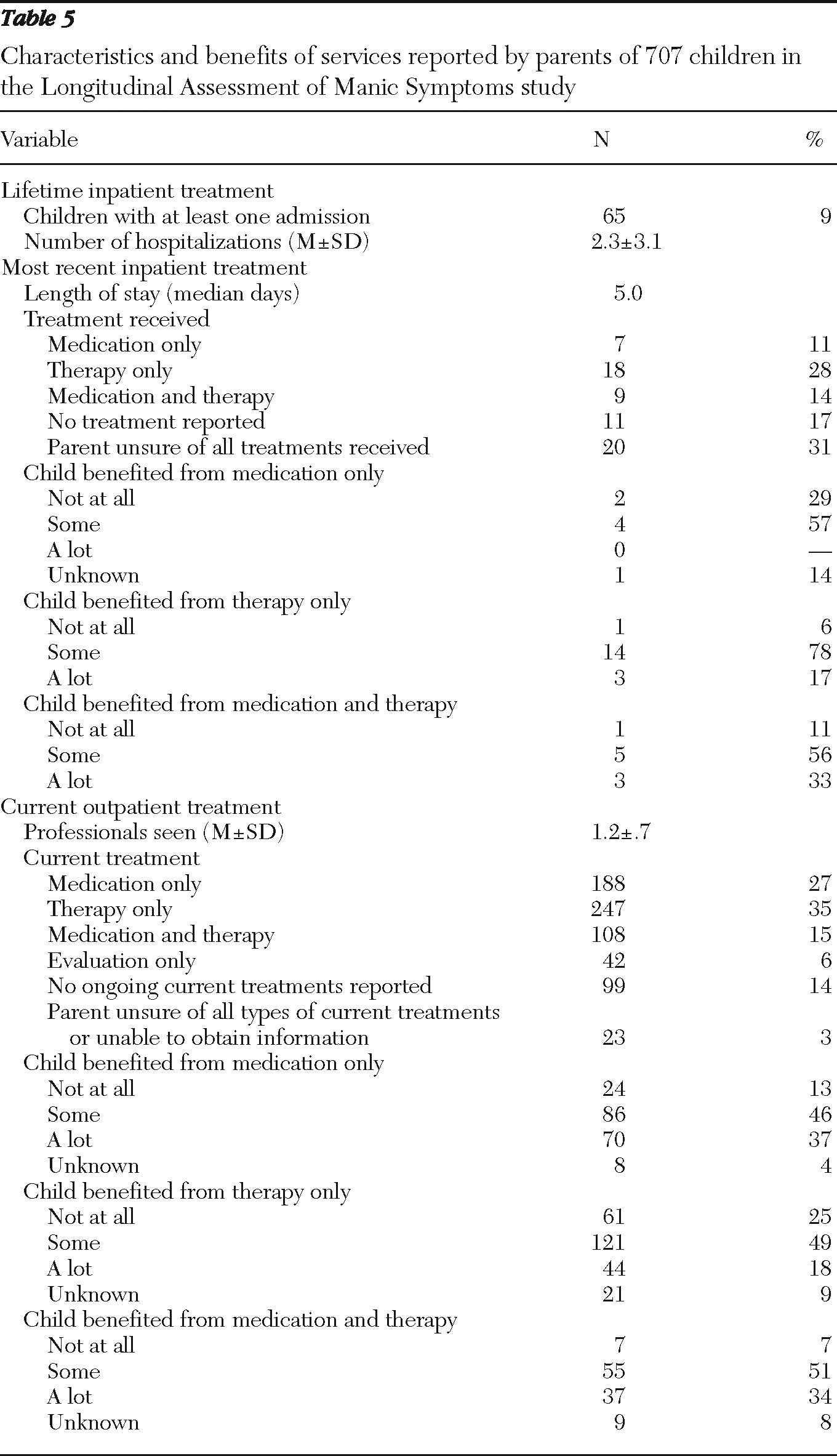

Characteristics and benefits of treatment

Table 5 summarizes data on characteristics and benefits of inpatient and outpatient treatment. Among children who had at least one lifetime inpatient hospitalization (9%), the mean number of hospitalizations was 2.3. The median length of stay for the most recent hospitalization was five days, and the most frequently reported type of treatment received was therapy only (28%), although many parents were unsure of the treatments their child received during the inpatient stay (31%) or did not report any treatment (17%). No parent of a child who received medication only during admission reported that the child benefited “a lot,” and 57% of these parents reported that the child benefited “some.” Most parents of children who received therapy only during the admission reported that their child benefited “some” or “a lot” from the treatment (95%), as did most parents of children who received both medication and therapy (89%).

Among the 689 children who were currently receiving outpatient treatment, children were seeing, on average, 1.2 professionals, and the largest proportion (N=247, 35%) was receiving therapy only. Most parents of children who were receiving medication only or both medication and therapy reported that their child benefited “some” or “a lot” from the treatment (medication only, 83%; both, 85%). A smaller proportion of parents whose children were receiving therapy only reported “some” or “a lot” of benefit (67%).

Discussion

As documented in previous research, our study found that children most frequently used mental health services in school and outpatient settings (

2,

23). Half of the youths in our study had received both outpatient and school services during their lifetime.

Youths with lower current levels of functioning and with comorbid mental disorders and older youths were more likely to have had an inpatient admission during their lifetime, which is consistent with previous findings (

7,

8). Even though this sample included only children aged six to 13, whereas other studies included adolescents, older age increased the likelihood of hospitalization in this study. As the duration of an illness continues, the intensity of intervention often increases, which frequently leads to hospitalization. As hypothesized, race was a significant factor in service utilization. As in past studies (

9), white children were more likely than children from other races to have received both medication and therapy in their lifetime, whereas children from other racial groups were more likely to have received only therapy. Children covered by Medicaid were less likely than those with other insurance to have received both medication and therapy in their lifetime and more likely to have received therapy only. In addition, children covered by Medicaid were less likely than children with other coverage to currently use two or more services. Low household income and restrictions in Medicaid coverage may have prevented these youths from obtaining all needed services. Because Medicaid reimbursement is low for physicians and because clinics can charge Medicaid for the full costs of counseling or therapy, therapy may be the first-line intervention for children with Medicaid coverage. Also, cultural differences in attitudes toward mental illness and appropriateness of specific interventions may influence utilization. Sex was not a significant factor in inpatient service utilization, but it was in use of outpatient services; girls were more likely than boys to have received only therapy in their lifetime. Of note, research findings on the impact of sex on service utilization among youths have not been consistent (

6,

8,

9).

The rate of lifetime inpatient admissions was higher among youths with a diagnosis of bipolar disorder than among those with a diagnosis of depressive or disruptive disorders. These results are consistent with those of past research, in which adolescents with bipolar disorder had higher hospital admission rates and medical visits related to injury and overdose than youths with other psychiatric disorders (

13). In both the bipolar spectrum group and the depressive disorders group, more than half of youths had received both medication and therapy during their lifetime. However, among children in the group with disruptive behavior disorders, the proportion of children who had received therapy only was larger than the proportion who had received both medication and therapy. This finding suggests that clinicians are more likely to employ only psychosocial interventions for strictly behavioral disorders. For children with oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, this approach is consistent with current treatment guidelines, although combination approaches might be optimal for some children with disruptive behavior disorders who do not respond to psychosocial interventions or for children with specific co-occurring disorders, such as those with ADHD and comorbid oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder (

24–

27). For children with mood disorders, clinicians are more likely to pair psychosocial interventions with medication, as indicated by treatment guidelines (

28–

30).

Contrary to our hypothesis, comorbidity and impairment were not consistently associated with service utilization in this sample. A possible explanation is that clinical need factors are more important for initial entry into the service system than for remaining in the system. Although these children were new to the clinics in the LAMS study, they had considerable previous mental health services utilization.

This investigation of use of inpatient and outpatient services showed that even though only 9% of the youths in the sample had a lifetime inpatient admission, these youths tended to be hospitalized multiple times (mean of 2.3 admissions). Research suggests that 24% to 37% of youths are readmitted to a psychiatric hospital within one year after discharge; age, sex, and clinical and family characteristics have all been found to be associated with readmission (

31). Parents of children in our study who were hospitalized reported that therapy only and a combination of medication and therapy were most beneficial. However, parents of children who were receiving outpatient treatment rated medication only and a combination of medication and therapy as more beneficial than therapy only. The data do not provide reasons for parents' ratings; however, possible explanations include greater satisfaction with having multiple providers helping their child, greater comfort with their child's receipt of medications at home, or unreasonably high expectations for improvement of complex conditions with therapy only. More research is needed to determine how parents evaluate treatment success in various settings.

Finally, only 46% of the children receiving outpatient services had received both medication and therapy during their lifetime. This is interesting in light of the large proportions of parents of children receiving care in either setting who reported that a combination of medication and therapy was beneficial. Emerging practice guidelines and research suggest that the combination of psychosocial intervention and medication is often the most effective option for treating serious mental illness among youths (

26–

30).

This study had several limitations. First, although 79% of eligible families agreed to complete the screening instrument, only 56% of those eligible agreed to participate in the longitudinal portion of the study. Therefore, generalizability of these data may be limited. Second, service utilization data were based on parent report and were not verified via another source. Third, even in this large sample of outpatient service users, small cell sizes limited some comparisons. Fourth, because the sample included children experiencing elevated symptoms of mania, service utilization may be overestimated compared with general outpatient samples. Fifth, because parents could not report on specific therapies received by their children, we could not examine the perceived benefit of specific therapies nor do we know whether the therapies were evidence based. Finally, these data are cross-sectional. Identification of patterns and predictors of service use and outcomes and predictors of improved outcomes will require data from the longitudinal portion of the LAMS study, which is currently in process.

Conclusions

Data from this sample of outpatient service users suggest that utilization of mental health services by children begins at a young age, is multimodal, and occurs in multiple service sectors. Thus coordination among service sectors is critical to optimize treatment effectiveness and efficiency. The finding that the type of services used was related to nonneed factors, such as insurance and race, suggests the continued need for research on treatment disparities. We found that the percentage of children receiving medication alone was low, compared with rates found in studies of administrative data (

32,

33). In addition, fewer than half of the children in the study received both medication and therapy, despite research findings indicating the effectiveness of combination treatment for many disorders. Thus efforts are needed to ensure that clinicians and families are educated about all treatment options. Finally, the increased likelihood of hospitalization among older youths points to the importance of early prevention and intervention efforts among younger children who begin to exhibit symptoms of mental illness. Early prevention and intervention efforts in both medical and educational settings, sectors where young children are commonly seen, may help to divert youths from restrictive treatment settings and to reach disadvantaged youths who are receiving suboptimal or no mental health treatment.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by grant R01-MH073967 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The conclusions presented are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of NIMH.

Dr. Findling has received research support, acted as a consultant to, or served on a speaker's bureau for Addrenex, Alexza, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Forest Laboratories, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson and Johnson, KemPharm, Eli Lilly and Company, Lundbeck, Neuropharm, Novartis, Noven, Otsuka, Pfizer, Rhodes Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, Seaside Therapeutics, Sepracore, Shire, Sunovion, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth. Dr. Frazier has acted as a consultant to Shire Development. Dr. Youngstrom has received travel support from Bristol-Myers Squibb. Dr. Arnold has received research support from or acted as a consultant to Eli Lilly and Company, Novartis, Shire, Curemark, AstraZeneca, and Noven. Dr. Birmaher has received research support from, acted as a consultant to, or served on a speaker's bureau for Forest Laboratories and Schering-Plough. The other authors report no competing interests.