Despite the public health burden of depression (

1–

6) and the public's increased willingness (

7) to seek effective treatments (

2,

8), many factors continue to act as significant barriers to treatment seeking (

9–

15), particularly for men (

16–

19). Structural barriers, such as limitations on insurance coverage and availability of providers, are important obstacles to help seeking (

20), but attitudinal barriers, such as stigma and social norms, are important impediments as well and are arguably more amenable to intervention. Gender role norms (

21), defined as socially reinforced, learned expectations of what it means to be a man or a woman in a given culture (

22), could lead to a reluctance to share personal information and admit that psychiatric services are needed.

Although many gender-based norms have been described for men and women (

23,

24), the toughness norm, which entails hiding pain and maintaining independence (

25), is presumed to be particularly salient for men (

14,

23,

26–

28) and may be especially relevant for understanding service utilization. Boys at an early age are taught to act tough and be autonomous (

26,

29–

31) and to refrain from seeking others' help to avoid signaling subordination and a loss of autonomy. Not surprisingly, men consistently have been less willing to seek help for mental disorders and more likely to prefer watchful waiting over active treatment in response to a depression diagnosis (

16–

18,

27). Some men are believed to face “double jeopardy”—the male gender norms that dissuade help seeking simultaneously exacerbate depressive symptoms (

32).

Although gender norms are commonly presumed to act as barriers to help seeking, the evidence for this position has been derived largely from small, nonrepresentative samples (

14,

26). We used data from the 2008 California Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) survey of a relatively large representative sample to examine the contributions of gender norms to preferences for various psychiatric treatments, including a “wait-and-see” approach involving no treatment at all. We tested three hypotheses, of which the first two concerned sex differences. Compared with women, men were expected to endorse higher levels of toughness and to report greater willingness to manage depression without the active involvement of a health professional. Third, we hypothesized that toughness would be inversely associated with willingness to seek active treatment for depression among both men and women. We also explored whether toughness mediated any sex differences in preferences to wait and see if the depression resolved on its own.

Methods

Procedures

Between July 2, 2008, and December 11, 2008, we followed up in a telephone call with a sample of respondents to the 2008 California BRFSS survey, carried out from January 24, 2008, through June 30, 2008.The BRFSS survey contains core components about demographic characteristics as well as about current health-related perceptions, conditions, and behaviors. Optional modules are developed or acquired by participating states. A detailed description of the items included in the core component, sampling information, and the optional and state-added items specific to the California version used in 2008 is available (

33). Included in the California state survey was the question, “Has a doctor or other health care provider ever told you that you have a depressive disorder (including depression, major depression, dysthymia, or minor depression)?” Responses to this item (yes or no) were used in these analyses to measure self-reported depression history.

The follow-on survey consisted of a 20-minute telephone interview designed to assess participants' current depression symptoms, attitudes toward depression and depression treatment, and adherence to the gender-linked norm of toughness. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the University of California, Davis.

Because depression was the focus of the follow-on survey, participants who reported a history of depression were oversampled approximately threefold. These respondents (N=391) constituted 38% of the entire study sample of 1,054 individuals. Sampling rates for the follow-on survey were calculated on the basis of standard definitions of the American Association of Public Opinion Research (

34). The response rate was 49%, excluding households whose eligibility could not be determined. The cooperation rate (responding households generating a complete interview) was 61%, excluding households in which the eligible party was physically or mentally unable to be interviewed. More information about sampling procedures is available elsewhere (

35).

Measures

Toughness was assessed using a modified version of the tough-image subscale from an update by Fischer and others of the Male Role Norms Scale, originally created by Thompson and Pleck (

25,

36). Participants respond on a scale of 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) to four items related to the need to look tough: “People should always try to project an air of confidence even if they really do not feel confident inside”; “A good motto to live by is, ‘When the going gets tough, the tough get going’ ”; “When people are feeling a little pain, they should try not to let it show very much”; and “People must stand on their own two feet and never depend on other people to help them do things.” Although the scale was originally designed for use with men, items were rewritten in gender-neutral language so that they could be answered by both men and women. The scale was shown to be internally consistent (Cronbach's

α=.63 for both men and women). Responses were reverse-scored and summed so that higher scores (from a possible range of 4 to 20) indicate greater desire to project a tough image.

Treatment preference was determined by asking participants to indicate which of four options they would prefer if they had depression—taking antidepressant medication daily for at least six to nine months, going to counseling every week for at least two months, taking medication and going to counseling, or waiting to see what happens without treatment. For the analysis, the first three responses were collapsed into one active-treatment category and compared with the wait-and-see approach.

Current level of depression was assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire nine-item depression scale (PHQ-9), which has been shown to be a valid measure of depression symptoms in the general population (Cronbach's

α=.86) (

37). Participants are asked to what extent they had experienced nine symptoms over the past two weeks. Possible responses are 0, not at all; 1, on several days; 2, on more than half the days; or 3, on nearly every day. Possible scores range from 0 to 27, with higher scores indicating greater depression severity.

In the BRFSS survey, participants were asked to provide their sex, age, race, ethnicity, and highest level of education. They were also asked to indicate if at any time in the past 12 months they needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost.

Analyses

All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 11.0, and accounted for the complex survey design of both the BRFSS and the subsample of the current survey (which oversampled persons with a depression history) to yield appropriate standard errors and population parameter estimates. Participants for the analyses reported here were sampled from two strata—those with and those without a self-reported history of depression diagnosis. California BRFSS weights were used and were adjusted for the oversampling of participants with a history of a depression diagnosis. Two participants did not provide a preference for treatment, and one did not indicate level of education. Thus analyses are based on a final sample of 1,051 participants.

The dichotomous dependent variable identified as preference to wait and see without seeking active treatment was analyzed using logistic regression. Toughness was analyzed using linear regression. Variable inflation factors were examined in all models to assess risk of multicollinearity and were found to be within acceptable levels (<6). To determine whether toughness mediated any sex differences in treatment preference, an approach conceptually similar to that proposed by Baron and Kenny (

38,

39) was used. The “suest” command in Stata was used to test whether the product of the coefficients relating sex to toughness and toughness to treatment preferences was significantly different from zero.

The magnitude of mediation of toughness in sex difference in treatment preference was found by factoring into direct and indirect effects the ratio of the expected odds of treatment preference when the participant was female to the expected odds when the participant was male; the expected odds were calculated on the basis of expectations of the conditional distributions of toughness among female participants and male participants, respectively. The ratio of expected odds reflects both the effect of sex directly on treatment preference as well as the difference in the distribution of toughness due to sex. In terms of the models used here it is represented by exponentiating the sum of the sex-treatment preference regression coefficient with the product of the sex-toughness and toughness-treatment preference regression coefficients. The indirect effect was calculated by multiplying the sex-toughness and toughness-treatment preference regression coefficients and exponentiating the product. Given the directional hypotheses, one-tailed significance tests were used for hypothesis testing analyses; otherwise, two-tailed tests were used.

Results

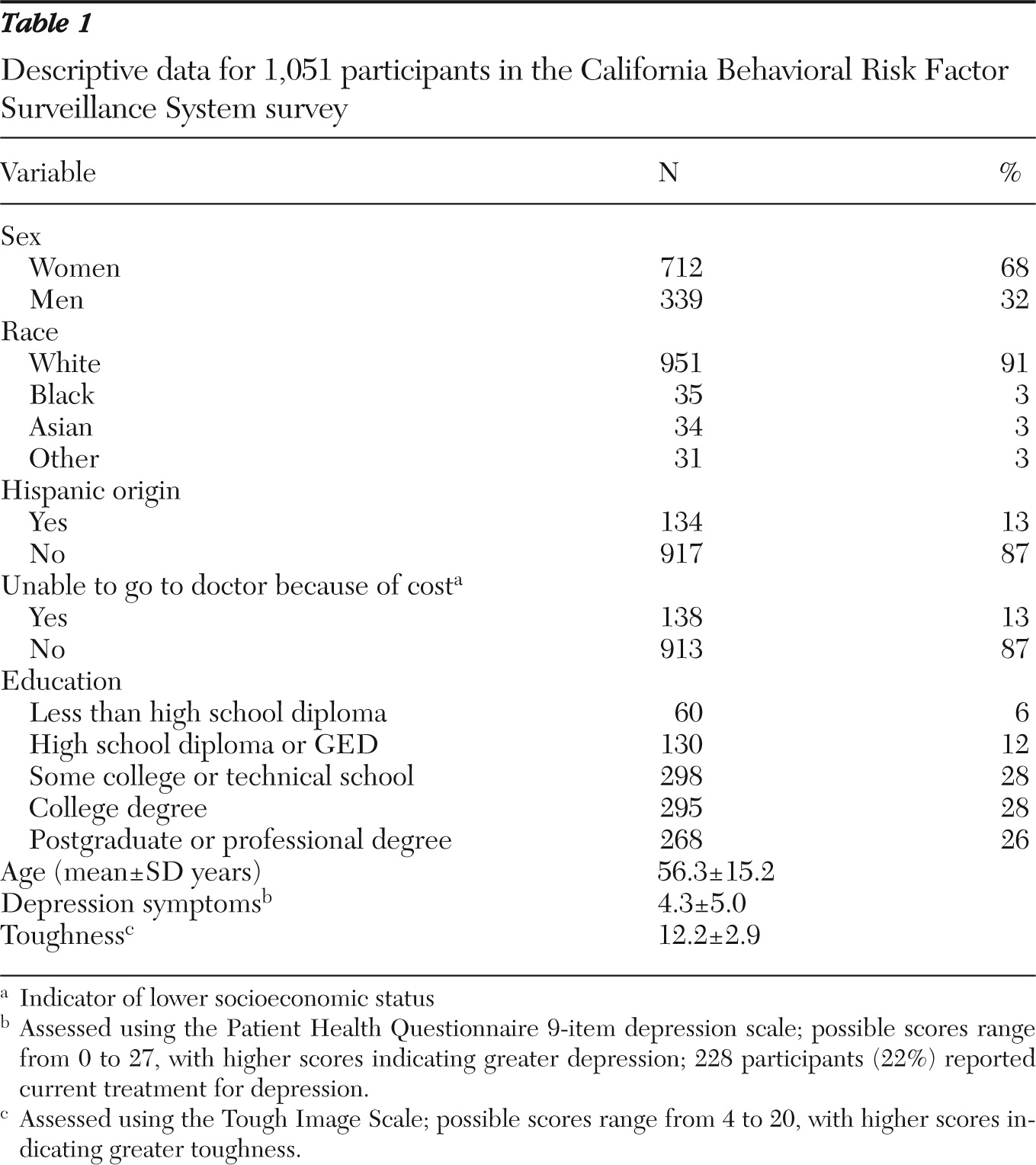

Table 1 presents descriptive data for the 1,051 respondents. A total of 115 (11%) indicated that if they had depression they would prefer to wait and see what happens without seeking treatment.

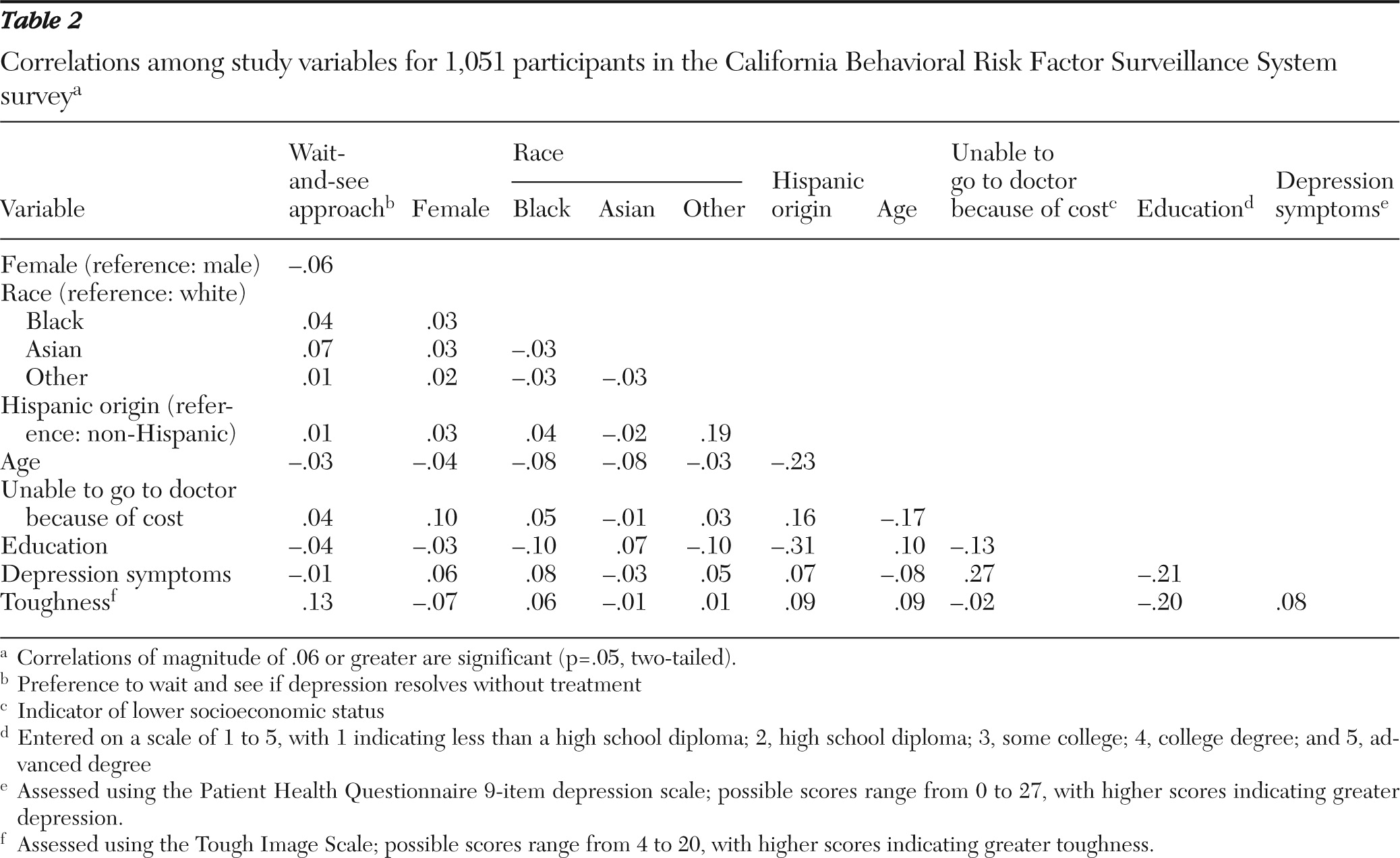

Table 2 presents the correlations among all variables.

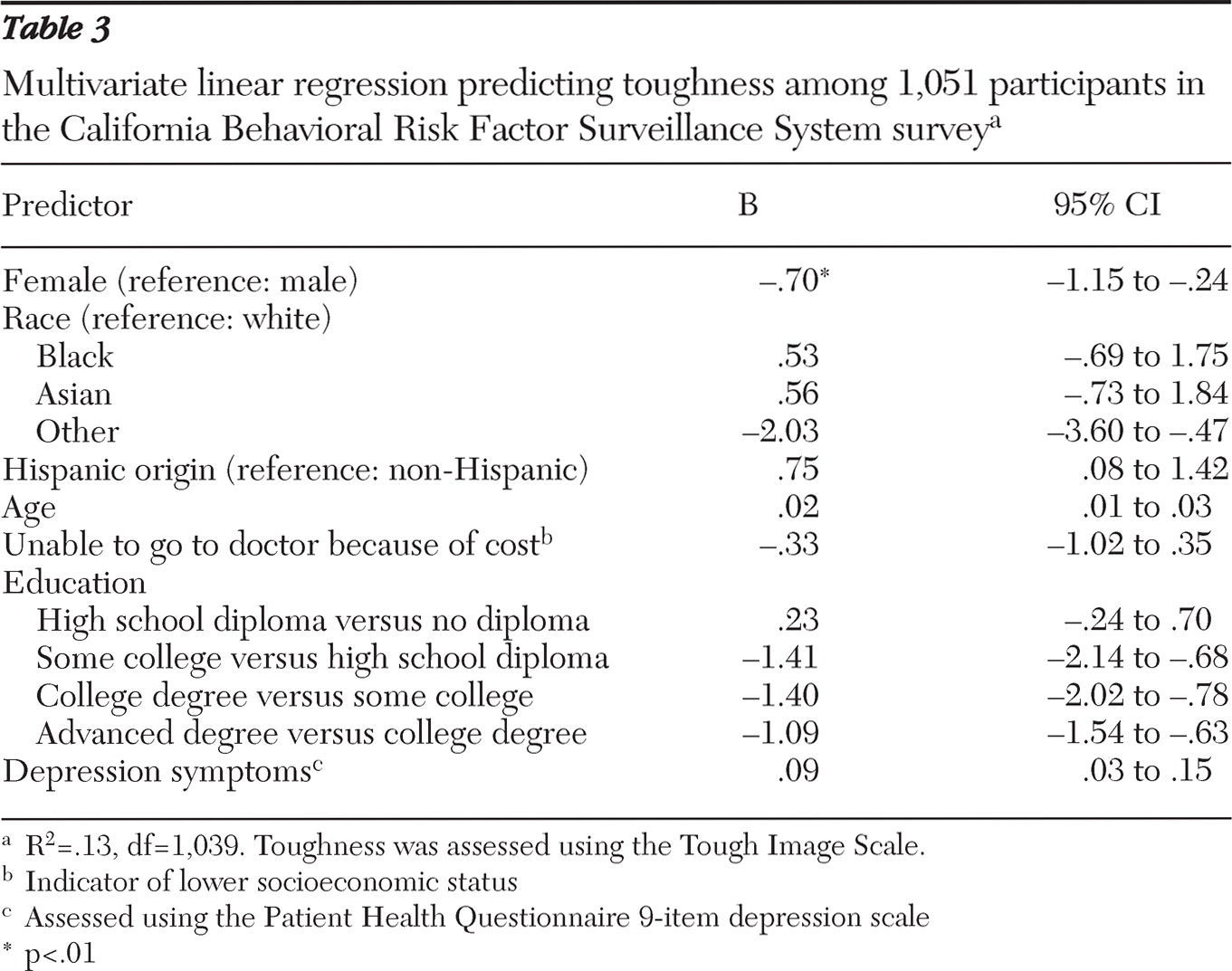

Table 3 provides the results of the multivariate linear regression analysis of variables that predicted toughness.

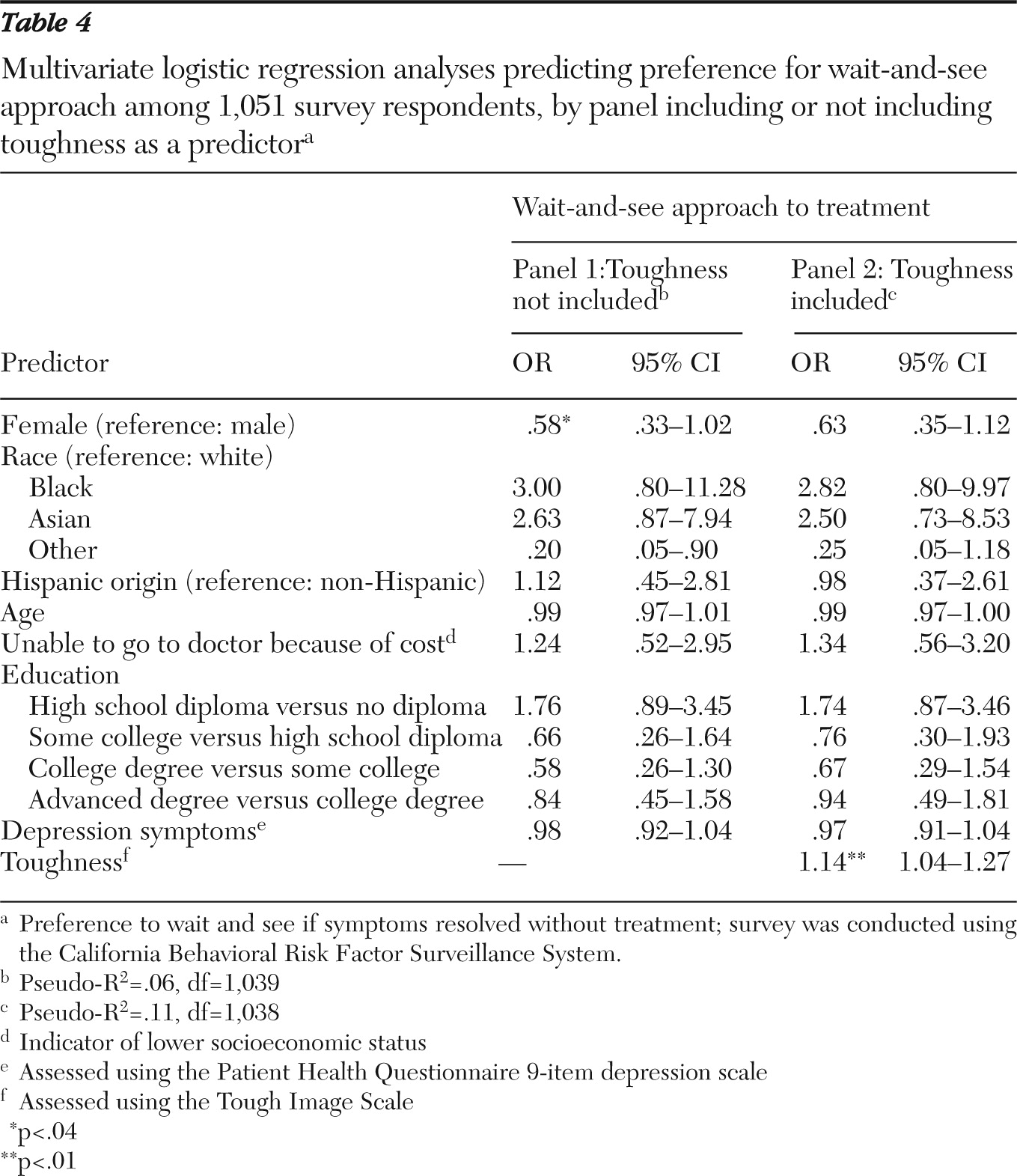

Table 4 presents the multivariate logistic regression analyses of variables that predicted a preference to wait and see if the depression resolves without treatment. Toughness is included as a predictor in panel two but excluded in panel one.

In support of the first two hypotheses, men scored higher on toughness (B=−.70, p<.01) (

Table 3) and showed a greater preference to wait and see if symptoms would resolve without treatment (OR=.58, p<.04) (

Table 4). In support of the third hypothesis, toughness was related to a greater preference to wait and see among both men and women (OR=1.14, p<.01) (

Table 4). When toughness was included in the treatment preference analysis, sex no longer significantly predicted treatment preference. The mediational analysis revealed that toughness partially mediated the sex difference in help seeking, modifying the ratio of expected odds by a factor of .91 (95% confidence interval [CI]=.82–.99, df =1,049, p<.03), explaining 18% of the original sex difference in help-seeking preference.

Discussion

This study tested a priori hypotheses about sex differences in toughness, in treatment preferences, and in the relationship between toughness and treatment preferences. In support of these hypotheses, men scored higher on toughness and showed a greater preference to wait and see whether symptoms resolved before seeking treatment. As expected, an inverse relationship between toughness and preference for active treatment was confirmed.

These results support suggestions that toughness is a more salient norm for men and could explain their greater resistance to traditional or formal mental health treatment (

28,

32,

40,

41). The toughness norm teaches children that asking for help implies weakness and leads to a loss of independence (

25,

29,

30).

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to investigate the role of the toughness norm in women's treatment preferences. It is noteworthy that like men, women who scored higher on toughness were also less interested in seeking active treatment for depression. Nonetheless, 18% of the sex difference observed in preference to wait and see was mediated by toughness. Although other factors are likely at play, these findings support the position that sex differences in mental health help-seeking behavior can be explained, in part, by gender norms.

Notably, reporting symptoms of depression was positively related to toughness. Those who present themselves as relatively tough may possess certain psychological characteristics that exacerbate depression and, perhaps, other mental disorders. Restricted emotional expression has consistently been linked with depression (

42–

44) as well as other disorders such as alcohol and drug abuse that may mask depression (

45,

46). “Tougher” individuals may also refrain from or delay seeking help and as a result may be expected to experience more severe symptoms because they are not receiving help. Having a greater likelihood of experiencing depression and an increased resistance to seeking treatment can place people at added risk (

29). Those most in need of treatment are often the least likely to seek help.

Clinicians, public health officials, and policy makers interested in encouraging treatment-resistant populations to seek help for mental disorders ought to address gender norms. Attempts to bring depressed people to services could address toughness in one of two ways—through cultural interventions designed to modify gender norms, thereby decreasing the level of “toughness” in society, or through social marketing interventions designed to frame help seeking either as an act of toughness or at least as a behavior that is not inconsistent with being tough.

Attempts to change norms would require an extensive, prolonged social investment and policy changes. In such an approach, public health messages could focus on prompting people to question whether they need to act tough. Schools could also implement programs to encourage children to be more open with their emotions and more comfortable seeking help. This goal may be attainable in the longer term but is unlikely to have immediate effects on health services utilization for depression. Moreover, just as any community intervention may have unintended consequences (

47), iatrogenic consequences are possible.

A more pragmatic approach that could pay off in the shorter term involves developing targeted messages that represent help seeking as an act of toughness or at least an act that is not inconsistent with being tough (

27,

48). For example, the “Real Men. Real Depression” campaign communicated that it takes courage to seek help for depression (

49). The U.S. Air Force suicide prevention program also involved changes in norms of help seeking (

50). Recently, a public education campaign was launched to improve understanding among black women that the pressure they face to always appear strong to others does not preclude seeking help (

51).

When men and women believe that being tough and seeking help for depression are not mutually exclusive, they may be more willing to seek treatment. Public figures who are often considered tough (sports figures, stars of action movies, military personnel) could be used as spokespersons in social marketing campaigns encouraging help seeking for depression (

52,

53). The effects of such public admissions on treatment uptake now and in the future could be examined.

Seeking help for depression could be positioned as aggressive action that represents taking control of one's life and going on the offense—in other words, as a way to defeat depression. If depression treatment is able to be reframed in that way, adherence to the toughness norm may actually prove to help people overcome depression. Finally, the theme of tough people, women and men, getting help for depression could be introduced into popular art forms such as television and movies through the strategy of “infotainment” (

54). These examples serve as templates for interventions to increase the acceptance of depression care. Again, we would be remiss if we did not acknowledge that this approach could have unintended adverse consequences (

47).

This study has four noteworthy limitations. First, the research design required participants to imagine they were depressed, but differences in capacity to imagine depression were not assessed; we do not have the data necessary to determine whether findings attributed to toughness are better explained by other variables, including individual differences in the capacity to imagine what it is like to live with depression (

55), in mental health literacy (

56), or in emotional intelligence (

57). Second, participants were asked to imagine having been diagnosed with depression but not told how long the depression might have lasted. It is possible that those preferring a wait-and-see approach simply imagined that they had been suffering for less time and, therefore, felt less concerned about their depression.

Third, this study reports analysis of cross-sectional data. As with any cross-sectional study, no firm causal conclusions can be reached. Finally, this study presents secondary analysis of an existing data set. The population and measures were not specifically selected to assess the questions asked in this investigation. Therefore, further research with a study designed to specifically test the hypotheses are needed before firm conclusions can be reached.

Future research should determine whether gender norms explain sex differences in other stages of health service usage, including symptom awareness (

14) and treatment adherence (

58). Research should also continue to explore the role of the toughness norm in women's behavior, especially in relation to treatment-seeking behavior. From a public health perspective, the relationship between toughness and help seeking is perhaps best addressed among symptomatic people who have not previously been diagnosed as having depression or among those who had received a diagnosis of depression but had not been treated for it.