Recent statistics suggest that the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are also associated with an increase in prevalence of PTSD among veterans. Before the current Iraq conflict, PTSD prevalence among all veterans seen in primary care clinics at four VA medical centers was 12% (

3). Among veterans of Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), in Afghanistan, or Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), in Iraq, who began receiving VA care between April 1, 2002, and March 31, 2008, 36% received new mental health diagnoses. Of these, 58% received new PTSD diagnoses (

4).

Most veterans who are newly diagnosed as having PTSD receive some mental health care, but often they do not complete a comprehensive course of treatment. The VA specifically supports the use of two evidence-based PTSD psychotherapies, cognitive processing therapy and prolonged exposure therapy. Typically, these consist of nine or more treatment sessions (

4–

7). Among all veterans with recent PTSD diagnoses from VA providers, about two-thirds received any VA mental health care in the six months after diagnosis, and about half of those who received any mental health care received either a four months' supply of medication or at least eight sessions of counseling (

5). Among a national sample of OEF-OIF veterans, 80% of those with new PTSD diagnoses had at least one VA mental health follow-up visit in the following year, but only 27% attended nine or more mental health visits of any type within the year (

4). Predictors of having had nine or more mental health visits within 15 weeks of receiving a new PTSD diagnosis included having received the diagnosis in a mental health clinic, having had any comorbid mental health diagnosis, female gender, older age, living closer to the clinic, and having been seen primarily at a VA community clinic (

4).

Little is known about the extent to which veterans recently diagnosed as having PTSD receive specialty PTSD treatment, and one previous study of characteristics of patients (N=87) associated with receipt of PTSD specialty care did not find any significant predictors of the number of visits (

8). However, specialized PTSD clinics may be more likely than general mental health clinics to provide efficacious and adequate treatment for PTSD because of the providers' specialized training and expertise. Receiving a PTSD diagnosis in a PTSD clinic, compared with in a general mental health or general medical clinic, has been shown to predict receiving an adequate course of treatment (

5). Among VA mental health treatment settings, a follow-up visit to a PTSD clinic is much more likely than a visit to a general mental health clinic or primary care clinic to include psychotherapy (

5).

Andersen's (

9) behavioral model of service utilization characterizes predictors of health services utilization as predisposing, enabling, and need factors. It has been used in mental health services utilization research that concerns veterans with PTSD (

10), veterans filing VA disability claims for PTSD (

11), and veterans with new mental health diagnoses (

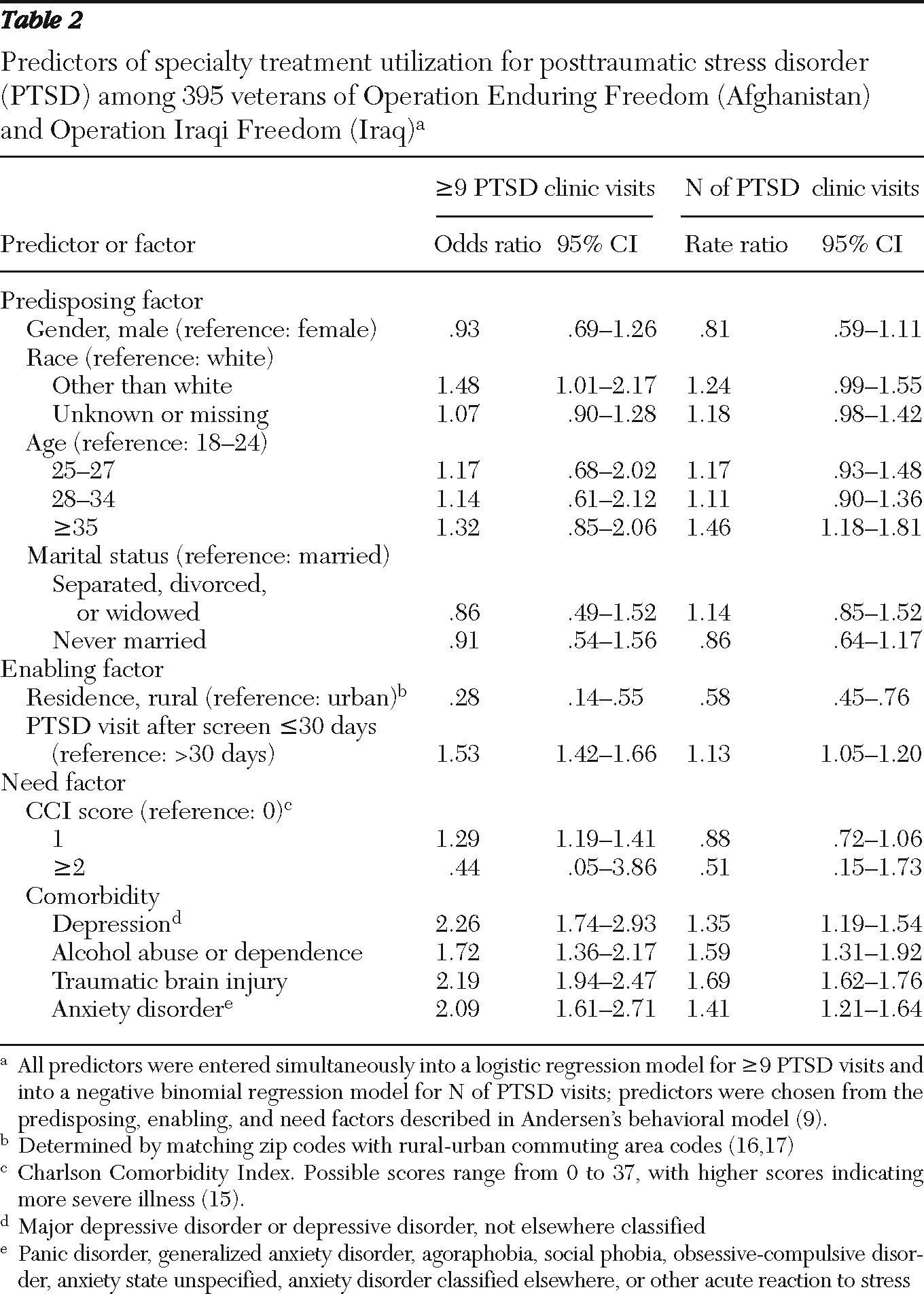

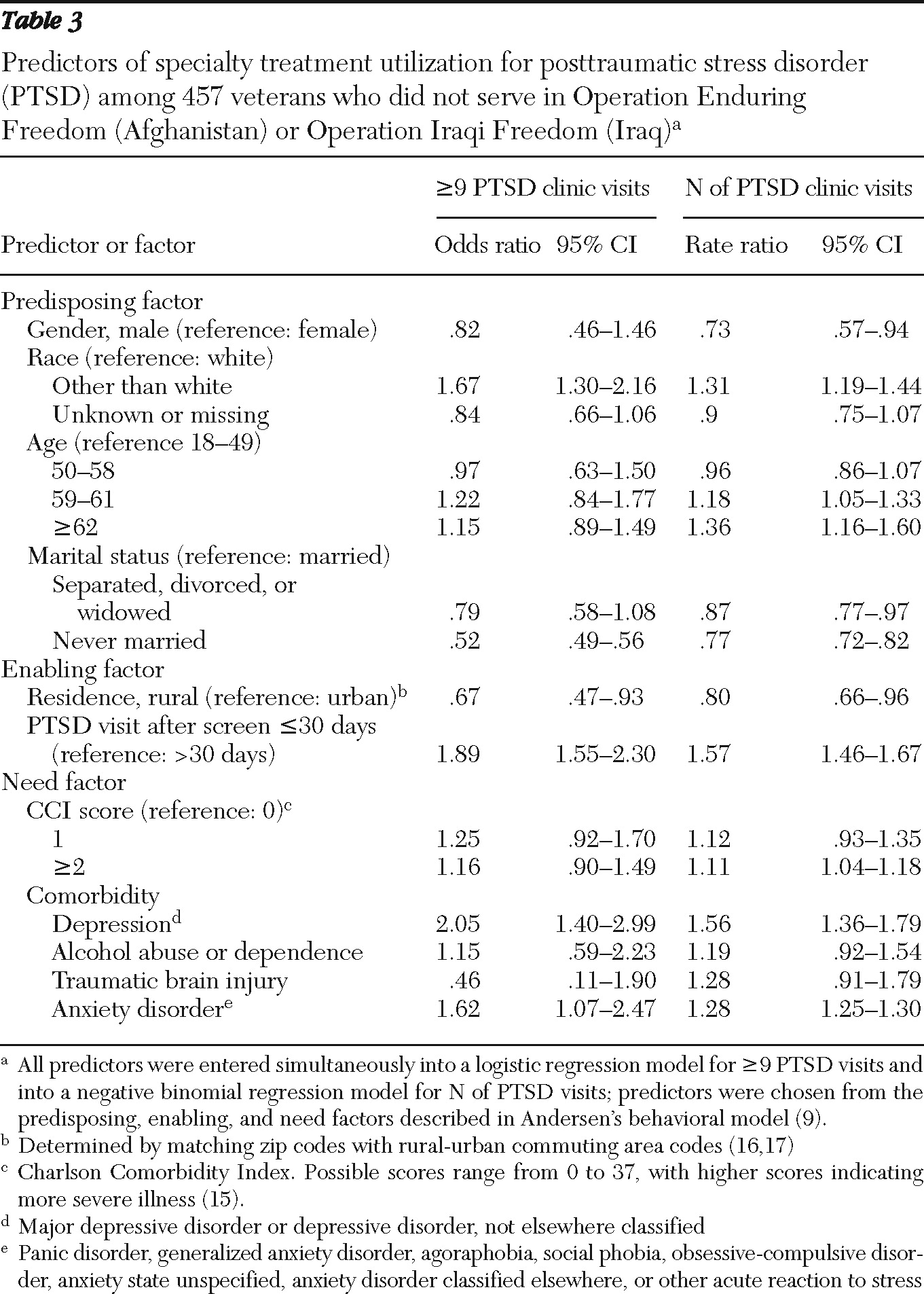

4). The primary objectives of our study were to describe PTSD specialty treatment received and, using Andersen's model, to identify predictors of receiving minimally adequate specialty treatment, defined as nine or more visits in 12 months, among veterans newly diagnosed as having PTSD who attended at least one visit to a specialized PTSD clinic. A secondary objective was to examine differences in and predictors of receipt of minimally adequate specialty treatment among OEF-OIF veterans and non-OEF-OIF veterans.

Discussion

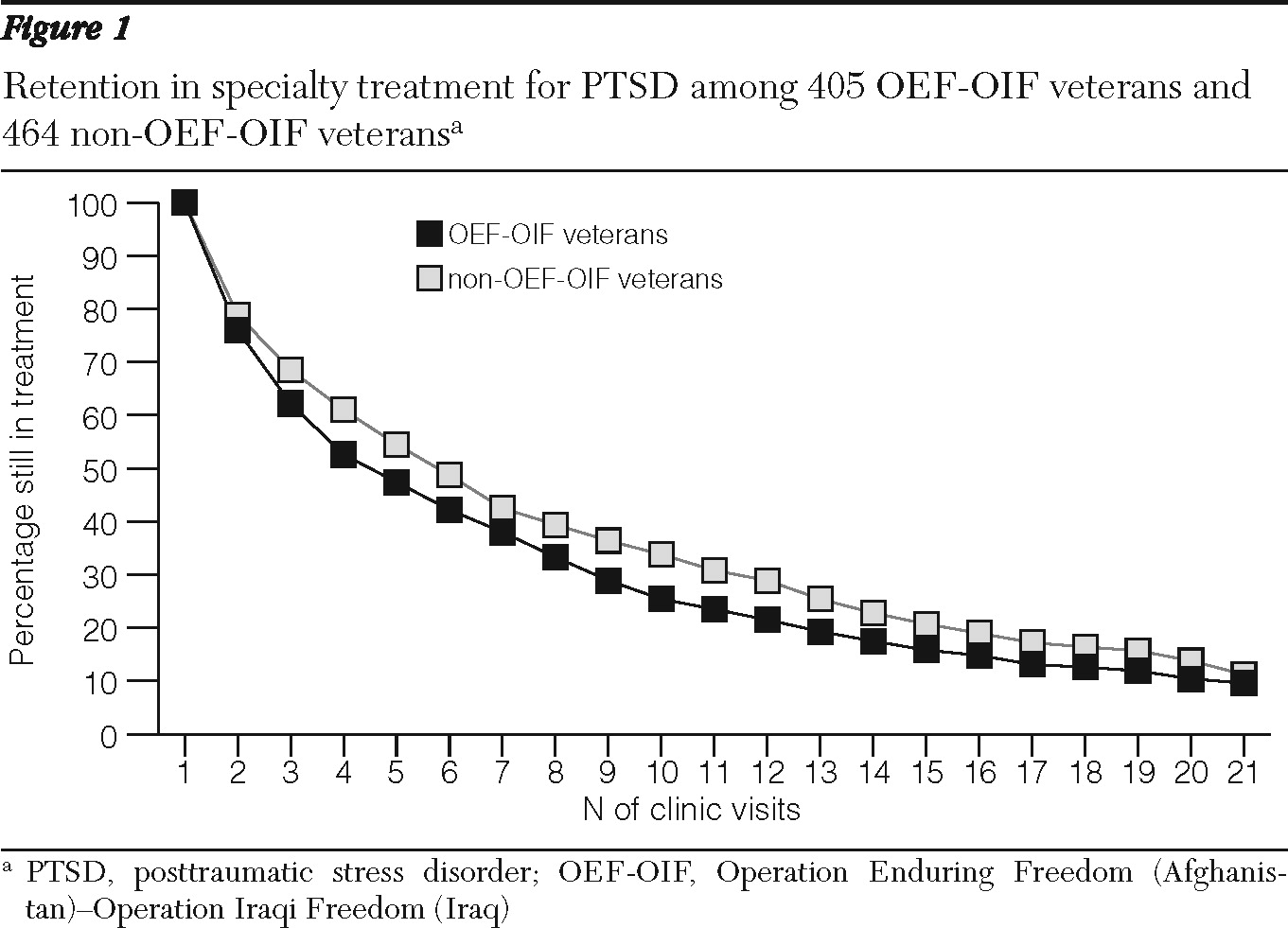

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine correlates of minimally adequate specialty treatment in VA PTSD clinics and to describe PTSD specialty treatment utilization by veterans newly diagnosed as having PTSD after a positive screen. Only about one-third of veterans who began PTSD specialty treatment received minimally adequate specialty treatment. Several factors were associated with receipt of minimally adequate specialty treatment, including attending initial PTSD clinic visits within 30 days of positive screens, living in urban locations, and having psychiatric comorbidities.

We believe that although the data do not allow us to differentiate between PTSD clinic visits for psychotherapy or medication management, they may provide an initial estimate of receipt of specialized psychotherapy for PTSD. The proportion of veterans who received minimally adequate specialty treatment (33%) was comparable to the finding by Spoont and others (

5) that 28% of veterans who received PTSD diagnoses in PTSD clinics attended at least eight counseling sessions. That study, which also excluded veterans with any recent history of VA mental health care, found that about 69% of follow-up visits in PTSD clinics involved psychotherapy (

5). The rate of receipt of minimally adequate specialty treatment found in this study is also comparable to the rate of receipt of adequate psychotherapy for depression and anxiety among patients in community samples (

21–

23). Further study is necessary to determine what proportion of patients, among those receiving minimally adequate specialty treatment, utilize evidence-based psychotherapies.

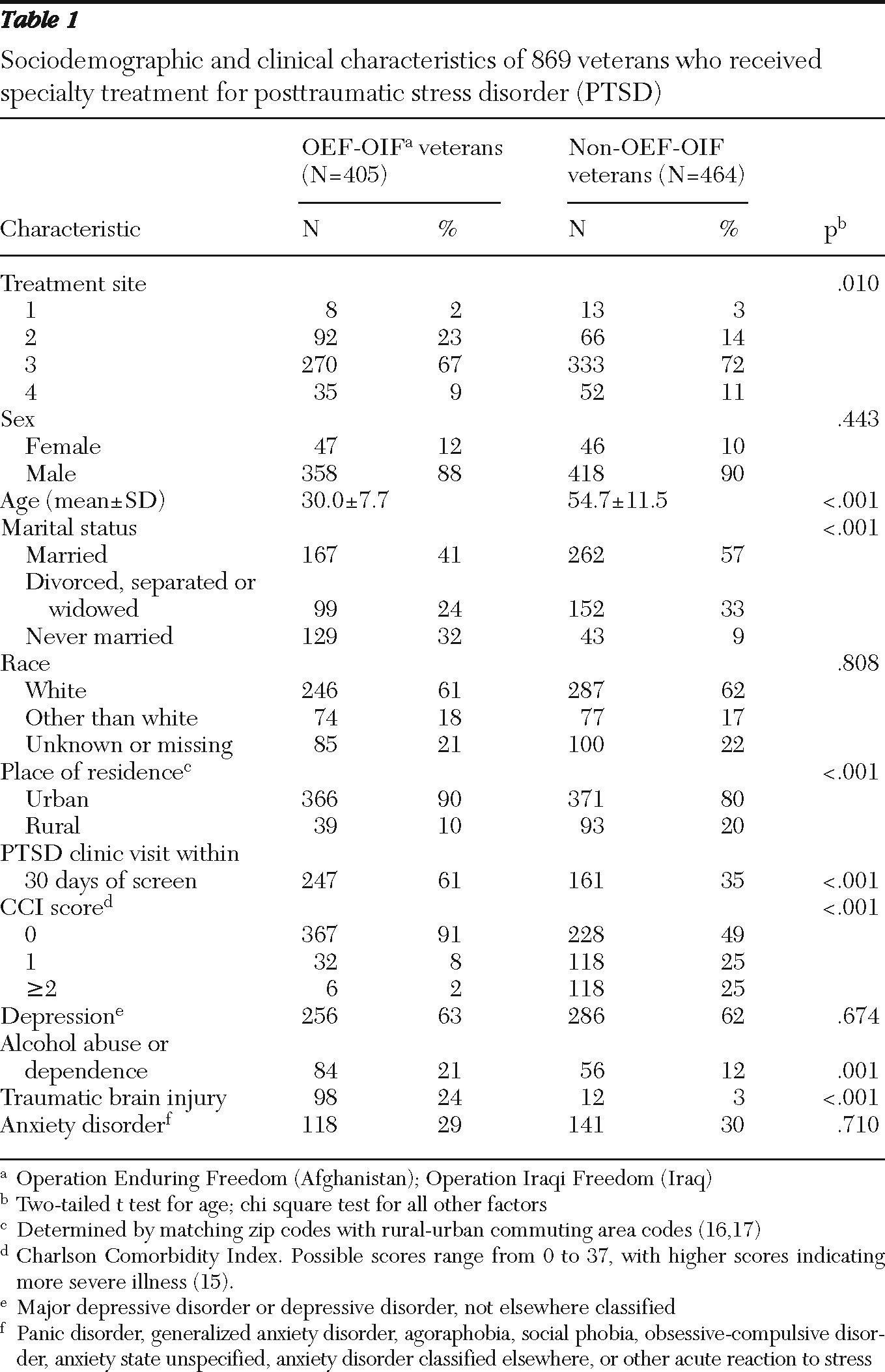

The clinical significance of decreased receipt of minimally adequate specialty treatment and attendance of fewer visits by OEF-OIF veterans is unclear, although several factors may contribute. For example, Vietnam veterans, who are older, may respond differently to treatment than OEF-OIF veterans (

24). An older cohort might be more likely to persist in treatment because of their age, time since trauma, PTSD chronicity, or other factors (

24). Despite attending fewer visits and being less likely to complete minimally adequate specialty treatment, OEF-OIF veterans were more likely to receive an initial PTSD visit within 30 days of a positive screen. This finding may suggest decreased access to services for Vietnam veterans because of limited treatment resources. Alternatively, older veterans with more chronic PTSD who did not serve in OEF or OIF may feel less urgency to initiate treatment but have more motivation to continue receiving treatment after initial engagement, compared with the OEF-OIF veterans.

Our findings confirm the usefulness of the behavioral model in considering predisposing, enabling, and need-related factors that may influence PTSD specialty treatment utilization. Regarding predisposing variables, marriage was predictive of receiving minimally adequate specialty treatment among veterans who did not serve in OEF or OIF, possibly because it confers increased social support for getting treatment or because veterans who are able to maintain marital relationships are also more likely to continue in treatment relationships.

Our findings associating race other than white with receipt of minimally adequate specialty treatment are consistent with some (

25) but not all (

26) previous studies of veterans. Psychotherapy for PTSD may be more accessible to nonwhite patients in the VA system than it is in the community, where white patients are more likely to seek PTSD treatment (

27). Enabling variables, including geography and timing of the first PTSD visit, are considered the most amenable to interventions to change health service distribution (

9). Living further from the VA has previously been found to correspond with decreased receipt of adequate mental health treatment for PTSD (

4). Our findings regarding the need variable of psychiatric comorbidities, particularly depression and anxiety disorders, support previous findings that psychiatric comorbidities predict both PTSD treatment initiation and receipt of adequate mental health treatment for PTSD (

4,

10,

28).

The study's limitations, including two characteristics of the sample, should be noted in interpreting our findings. We included only veterans new to VA mental health care (

5), a decision that may have caused us to observe lower rates of receipt of minimally adequate specialty treatment. This sample characteristic may preclude generalizability to all veterans receiving care at the VA but also provides a valuable perspective on individuals in the early stages of treatment. We included only veterans who received at least one PTSD clinic visit, in order to minimize variance due to unmeasured factors related to VA providers, facilities, and systems that have an impact on initial access to PTSD clinic treatment. Such structural components of resource organization are the most difficult to define and to relate to utilization patterns (

10). However, limiting the sample to those who attended PTSD specialty clinic visits also may have selected for veterans who were motivated and who perhaps had more severe PTSD than veterans who were not referred for PTSD specialty care.

We sought to measure PTSD treatment plausibly related to the index screen; thus a veteran who began treatment but did not complete nine visits in the 12 months following the screen was not considered to have received minimally adequate specialty treatment, even if he or she ultimately completed treatment. It is not known whether delays in treatment receipt affected clinical outcomes. In post hoc analyses, extending the follow-up period to 365 days after the first PTSD clinic visit slightly increased the rate of completion of minimally adequate specialty treatment and of number of visits in both cohorts; it also slightly widened the gap between veterans who had or had not participated in OEF or OIF in the number of visits received and in the proportion receiving minimally adequate specialty treatment.

We did not include a measure of pharmacotherapy, because medication for PTSD is prescribed by a variety of VA providers. About half of all veterans in our sample received at least 120 days' supply of antidepressant medication (

5). Combining this measure of pharmacotherapy with minimally adequate specialty treatment would yield an overall rate of adequate treatment comparable to or greater than the rates that have been found among U.S. patients with depression (

29) or various psychiatric diagnoses (

30).

Several other limitations apply to interpretation of our data. We could not confirm the accuracy of PTSD diagnoses made by clinicians. We could not assess the impact of VA disability ratings for PTSD on treatment completion rates because the data did not contain information on the temporal relationship between the assignment of disability ratings and treatment attendance. Any implications about our findings related to race are limited by the significant proportion of missing data (

Table 1).

Further research would be needed to evaluate whether rural veterans are receiving less PTSD treatment, different PTSD treatment, or both; VA facilities may use contracts or referrals to rural community providers for veterans who cannot travel to other VA facilities for PTSD specialty care (

31). The effect of receiving the first PTSD clinic visit within 30 days of a positive screen result may reflect patient motivation, treatment access factors, and PTSD symptom severity. We cannot interpret the impact of having psychiatric comorbidities as causal because of the possible confound between treatment utilization and receiving additional diagnoses.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This work was supported by VA Health Services Research and Development Service projects REA 06-174 and the Pacific Northwest Mental Illness Research and Education and Clinical Center. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. The authors acknowledge James M. Sardo, Ph.D., Miles E. McFall, Ph.D., Larry Dewey, M.D., William Minium, and Sara Smucker-Barnwell, Ph.D., for assistance in gathering information about facility PTSD services; Michael C. Leo, Ph.D., for statistical consultation; and Lauren M. Denneson, Ph.D., for editorial assistance.

The authors report no competing interests.