Individual placement and support (IPS) is a well-defined model of supported employment for clients with severe mental illness (

1). Competitive employment rates for IPS programs are more than twice those for other vocational approaches (

2).

However, despite strong and consistent findings for job acquisition, observers have noted that job retention rates for IPS clients are fairly brief (

3–

6). One widely cited review of eight studies concluded that job tenure for clients enrolled in supported employment was typically less than four months and ranged from 70 to 151 days (

4). However, the studies reviewed were conducted between 1994 and 2004 and are now dated. Half of them did not examine IPS supported employment, and most had small sample sizes (median=47) and relatively short follow-up periods of nine to 18 months.

Another review commonly cited to substantiate the claim of short job tenure for IPS is even more dated (

3). A further confusion in the literature is based on the finding in controlled studies that IPS participants and those in the control group who obtain work have similar durations of job tenure (

2). This finding has been erroneously interpreted to mean that IPS does not help clients keep jobs, an interpretation that fails to recognize that such comparisons are between nonequivalent samples.

A recent review reported mean tenure of 22 weeks in longest-held job among 317 IPS clients in six controlled trials of IPS with 18- to 24-month follow-ups (

2). Although that review offers the best available evidence, it is time to take a fresh look at the job tenure issue for high-fidelity IPS programs and to use standardized measures of job tenure and an adequate sample and follow-up period. To avoid some of the limitations mentioned earlier, this study estimated job tenure by defining the sample and follow-up period for IPS clients after they obtained competitive employment, thereby differentiating the question of job acquisition from job tenure.

Methods

As part of a study on patterns of employment services, 142 clients who were enrolled in IPS programs at four sites were followed for two years after they began a competitive job. At study enrollment, demographic and other background measures were collected. Clients were tracked with monthly reports completed by their employment specialists. Of the total sample, 82 were clients who were prospectively enrolled within one month of obtaining employment (prospective sample), and 60 were clients who were retrospectively enrolled from the time they started a job in the previous six months (retrospective sample).

Study participants were enrolled from November 2005 until June 2007. Two-year follow-up data collection ended in June 2009. This study was reviewed by the Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis Institutional Review Board and was deemed an exempt study.

Four urban sites located in the Midwest region of the United States participated in the study. Three sites were community mental health centers, and each operated a single IPS program. The fourth site was a large psychiatric rehabilitation center with three IPS teams. In addition to offering IPS, all four sites provided comprehensive mental health and substance abuse services.

To ensure high fidelity to the IPS model, we used the 15-item IPS Fidelity Scale, a behaviorally anchored instrument completed by independent assessors. The scale has excellent psychometric properties, discriminating between programs adhering to evidence-based supported employment and other vocational models, and it is correlated with higher competitive employment rates (

7). We used a fidelity score of 60 or higher as the cutoff for study inclusion (

8). One of the six IPS teams had a fidelity score of 61; the rest had fidelity scores of 64 or higher.

Participants were clients with severe mental illness aged 18 and older and enrolled in IPS at one of the participating sites. To be eligible, a client was required to be identified by an employment specialist as meeting the study criteria: currently working at least ten hours per week in competitive employment and having begun a competitive employment position within the preceding six months. Most IPS clients who work competitively do so at least ten hours a week. In one large database of four IPS trials, 74% of IPS clients worked at least ten hours a week (K. Campbell, personal communication, October 29, 2010). The study enrolled all eligible clients during the study period.

Study noncompleters were defined as participants who terminated IPS services before the final month of the 24-month follow-up period; only those completing 24 months were considered study completers. No employment data were obtained for noncompleters after program termination. Reasons for termination before 24 months were varied; some noncompleters were successful graduates; others dropped out of the program.

At each site, we provided a project overview to the IPS team. During the course of the study, all 35 employment specialists employed by these teams participated. After receiving training from the second author, employment specialists at three sites used a Web-based system for completing the baseline questionnaire and the monthly employment update. Each month, employment specialists were prompted with an e-mail containing an electronic link to the survey for each client enrolled in the study and were contacted for clarification when data were missing. Employment specialists received $15 for participating in the study and $5 for each monthly survey completed per client enrolled in the study. At the remaining site, an on-site research assistant managed data collection.

At study entry, information on demographic characteristics, employment history, diagnosis, Social Security entitlements, and current employment was collected. The monthly employment update included information on employment status (employed or unemployed), job losses, job starts, job type, days worked during the past month, changes in hours worked per week, and changes in wage rate.

Job retention and job tenure have been operationally defined in diverse ways in the literature. Controlled trials have typically reported tenure in longest-held job, which is a more liberal index of tenure than time in first job obtained. Moreover, in the IPS model of supported employment, the overall goal is to help clients obtain competitive employment and to become steady workers (

9). Although tenure at a single job reflects job stability and is viewed as a positive outcome, IPS employment specialists do not regard job losses as failures. Employment in successive jobs, especially when the unemployment period is brief, is also considered a successful outcome. To avoid confusion in terminology, we used the term “duration of employment.” We defined two indices of duration of employment: total months worked (total number of months worked across the 24-month follow-up) and tenure in first job (number of months worked at the initial job). We also examined the number of months between the end of the first job and the start of the second job.

Results

The sample consisted of 142 clients, including 72 (51%) men and 70 (49%) women. The mean±SD age of the sample was 39.7±9.7 years; 96 (68%) clients were Caucasian, 38 (27%) were African American, four (3%) were Hispanic, three (2%) were Native American, and one (1%) was Asian American. Diagnoses included schizophrenia (N=44, 31%), schizoaffective disorder (N=26, 18%), bipolar disorder (N=46, 32%), major depressive disorder (N=20, 14%), and other disorders (N=6, 4%). A total of 24 (17%) clients had not completed high school, 52 (37%) had completed high school or had a GED, 47 (33%) were enrolled in college or technical school, and 13 (9%) were college graduates; educational data were missing for six clients.

Before entering supported employment, 53 (37%) had never held a competitive job; data on employment history were missing for 11 clients. A total of 47 (33%) were receiving Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI), 38 (27%) were receiving Supplemental Security Income (SSI), 17 (12%) were receiving both SSDI and SSI, and 26 (18%) were receiving neither; data on enrollment in entitlement programs were missing for 14 clients. The demographic characteristics of clients were generally similar across sites, although site 2 had a higher proportion of African Americans and site 1 had a somewhat higher proportion of clients diagnosed as having a disorder on the schizophrenia spectrum.

A total of 100 (70%) clients remained enrolled in IPS during the 24-month follow-up period, and 42 (30%) did not. Of the 42 noncompleters, four (3%) terminated during the first six months, 15 (10%) during months 7–12, 13 (9%) during months 13–18, and ten (7%) during months 19–24. Twenty-one (50%) noncompleters were employed at the point of termination.

Noncompleters did not differ in sex, diagnosis, educational background, Social Security status, residential status, or work history compared with completers, but they did include a higher proportion of African Americans (48% versus 18%; χ2=13.98, df=1, p<.001).

Across 24 months of follow-up, the total sample worked an average of 15.6±10.2 hours per week and 10.7±6.8 days per month. Limiting the statistics to periods in which clients were employed, clients worked an average of 23.5±8.3 hours per week and 16.4±4.2 days per month. Mean wage rate for working clients was $7.90±$3.00 per hour.

The most common job was in food service, held by 38 (27%) clients; 22 (16%) held retail positions, 14 (10%) held janitorial positions, and 11 (8%) held professional positions. Clients averaged 1.9±1.2 jobs over the 24-month period. Twenty-one (14.8%) clients remained employed at the same job for the entire follow-up period. Forty-eight (33.8%) clients held a single job during study participation but either lost the job or left IPS services before the 24-month follow-up period had ended. Of the remaining 73 (51.4%) clients, who had multiple jobs, 42 (30%) had two jobs, 14 (10%) had three jobs, nine (6%) had four jobs, and eight (6%) had five or more jobs.

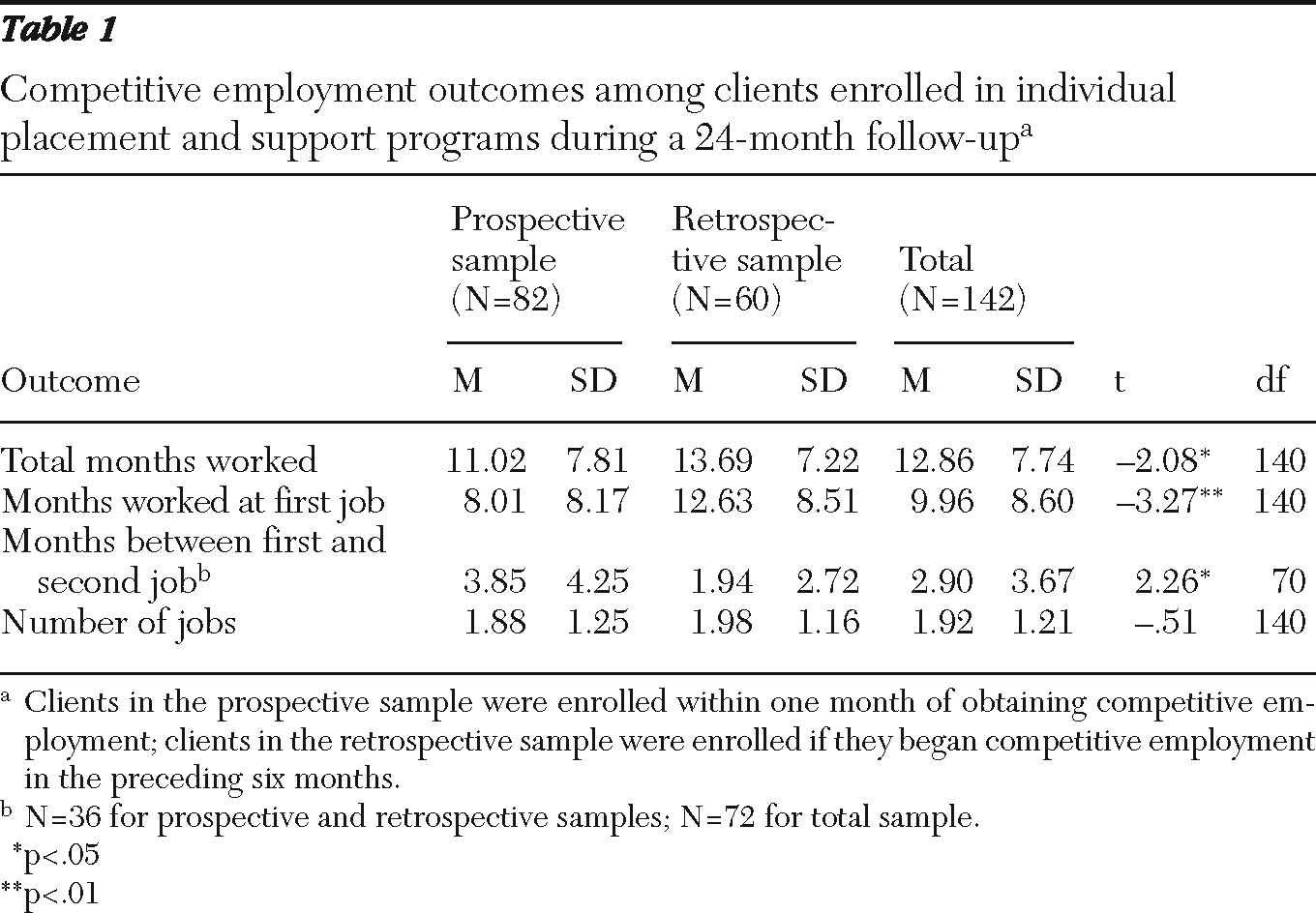

As shown in

Table 1, the total sample averaged 12.9 (median=11.0) months of employment across all jobs and 10.0 (median=7.0) months in the first job. Clients who had multiple jobs averaged 2.9 months of unemployment between the end of the first job and the start of the second. As also shown in

Table 1, the prospective sample had significantly fewer months of employment in the initial job and worked fewer total months overall during follow-up than did the retrospective sample.

Client characteristics generally were not associated with employment outcomes. Younger participants held more jobs than did older participants during the follow-up period (r=.26, p=.01). Mean number of months between the first and second jobs was longer for clients receiving both SSI and SSDI than for those without Social Security entitlements (5.5±5.6 versus 1.3±2.0; F=3.00, df=3 and 60, p=.04). No other background characteristic was associated with employment.

Discussion

The study sample had substantial success in maintaining competitive employment. Focusing on the prospective sample, which gives the most unbiased picture of job tenure for IPS clients who gain employment, we found that clients worked, on average, 11 months over the two-year period, and job tenure in the initial job averaged eight months, twice as long as reported in earlier reviews. Moreover, this study underestimated mean job tenure in that more than a quarter of the sample continued to work beyond the time of observation—15% of completers were still working at the end of the two-year follow-up, and 15% of noncompleters were employed at the time of termination.

Our findings suggest that among participants who began a competitive job (for at least ten hours a week) after enrolling in high-fidelity IPS, about 40% became steady workers. These findings complement the well-established findings from randomized controlled trials showing the effectiveness of IPS in job acquisition (

2). Putting these two set of results together, we conclude that about two-thirds of clients who enroll in IPS obtain competitive jobs. About 40% of those who started a job working ten hours a week became steady workers, working during at least half the follow-up period.

This study also documents the unsurprising finding that job tenure in a prospective sample is significantly less than in a retrospective sample. This finding serves as a reminder that in setting benchmarks for a field, the sampling methods are crucial.

Criticisms concerning short-term jobs in IPS are repeated in many public policy debates. Recently, a major federal official asserted that “[although] IPS realizes better outcomes, attachment to competitive labor market [is] tenuous” (

10). We suggest that this impression has been influenced by early studies, when the supported employment model was still being developed, and by follow-up studies of 12 to 18 months in duration, which may adequately measure the amount of time taken to find a job but not fully capture the tenure of employment. Reviews suggest that employment rates have steadily improved in IPS studies in the United States over the past decade (

2) A second issue is the choice of job tenure indicator; according to the IPS model of supported employment, cumulative time worked (at any job) is a more meaningful index of vocational success than is job tenure at a single job (

1). In contrast to many short-term studies, long-term IPS follow-up studies using the construct of “steady worker” (employed at least 50% of the follow-up period) have reported more favorable results on the indicator of cumulative time worked. Two long-term studies found that more than 50% of clients had become “steady workers” over a period of eight to 12 years after enrollment in IPS (

9,

11), a finding that gives a very different impression than does the literature criticizing supported employment as being limited to short-term jobs.

Thus, from perspective of the IPS model, the goal is not job tenure in a specific job but rather steady employment over the long term. Other perspectives, including that of the state-federal vocational rehabilitation system, emphasize sustained employment in a single job as the standard for a successful closure (

12). Performance-based funding systems also reward job tenure in a single position (

13), a practice that may not fit with the employment patterns for many client subgroups, such as the young adult population (

14), as suggested by our study.

Research is currently under way to improve job retention through cognitive remediation and other interventions (

4). Enhancements of the IPS model should be pursued, but excellent job-retention rates are possible now through close adherence to the IPS model. The break-even point for investing resources in better fidelity or in further enhancements of the IPS model has not been determined (

15).

This descriptive study has several limitations. First, it lacked a comparison group. Second, selection biases included convenience sampling of study sites in one geographic region and participant inclusion criteria, which excluded IPS clients who terminated their involvement before gaining employment, a subgroup that includes about one-third of clients enrolling in IPS (

2). Finally, employment specialists may have avoided enrolling clients with precarious job placements. In sum, the study sample was representative of more successful IPS clients.

Conclusion

The proportion of IPS clients who begin a long-term attachment to the labor market is higher than has sometimes been asserted in the literature. Long-term follow-up studies of IPS are needed. As this study suggests, short-term studies may not correctly forecast long-term outcomes.

Acknowledgments and disclosures

This study was supported by a subcontract from Virginia Commonwealth University Rehabilitation Research and Training Center (National Institute of Disability and Rehabilitation Research grant H133B040011). The authors thank the employment specialists and administrators at the participating study sites.

The authors report no competing interests.