Laterality of Epileptic Focus?

Since the suggestion by Flor-Henry (

69) of a preponderance of left-sided pathology in patients with schizophrenia-like psychosis, many studies have examined this issue. In the EEG studies, the majority opinion favors an excess of left temporal foci in the patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and schizophreniform psychosis (

62,

70), although there have been some negative laterality studies (

41,

65,

71). There are many problems with the available data. First, the rigor with which laterality was established differs across studies, and the use of surface EEG recordings to establish laterality is open to question. Second, the presence of an epileptic focus on one side does not mean that pathology is restricted to that side. Third, left-sided preponderance of temporal lobe foci may not be restricted to psychotic individuals, as the evidence supports a left-sided bias for temporal lobe epilepsy in general (

49). Fourth, there is emerging evidence that epilepsy patients with schizophrenia have generalized seizures even when they have a temporal focus (

3,

39). Fifth, the instruments and diagnostic criteria used for psychosis are language dependent, thus introducing a left-side bias (

58).

The neuroimaging studies that examined laterality were inconclusive. The CT (

63,

72) and MRI (

73) studies failed to demonstrate lateralized lesions, although the patients with hallucinations had higher T

1 values in the left temporal lobe. Two small functional imaging studies (

74,

75) provided preliminary evidence of greater left medial temporal lobe dysfunction in schizophrenia-like psychosis with epilepsy. A proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy study (

76) showed metabolic abnormalities in the left temporal lobe of patients with schizophrenia-like psychosis and epilepsy. The neuropathological studies (

68,

77) have not supported lateralization of pathology.

The laterality issue therefore remains undecided, but the importance of a left-sided focus is not striking. It is possible that the structural abnormality in epileptic psychosis is not lateralized, and is possibly bilateral, but that the functional abnormality is predominantly left-sided. However, right-sided abnormality seems to be sufficient, and generalization of the epileptic disturbance is commonly present.

Neuropathological Studies

Neuropathological studies of schizophrenia-like psychosis with epilepsy have been limited. A large series from London, drawing on subjects with histories of temporal lobectomies, has been reported (

77,

79). Taylor (

79) commented that epilepsy patients with schizophrenia-like psychosis were less likely to have mesial temporal sclerosis and more likely to have alien tissue lesions (small tumors, hamartomas, and focal dysplasias). In the report by Roberts et al. (

77), 40% of patients with schizophrenia-like psychosis and epilepsy had mesial temporal sclerosis, 20% had alien tissue gangliomas, and 20% had no lesions (49%, 4%, and 15% of the total epileptic group, respectively). Histories of birth injury, head injury, and febrile convulsions were not overrepresented in the group with schizophrenia-like psychosis, but the frequency of alien tissue tumors and early onset of seizures suggested a developmental lesion in the medial temporal structures that had been physiologically active from an early age. Stevens (

67), on the other hand, reported widespread pathology in six cases of epilepsy and psychosis; the pathology included the hippocampus, hypothalamus, thalamus, pallidum, and cerebellum. In a study by Bruton et al. (

68), epileptic patients with schizophrenia-like psychosis had larger ventricles, more periventricular gliosis, more focal damage, and more periventricular white matter softenings than nonpsychotic epileptic comparison subjects, but similar rates of mesial sclerosis, suggesting greater nonspecific neuropathology.

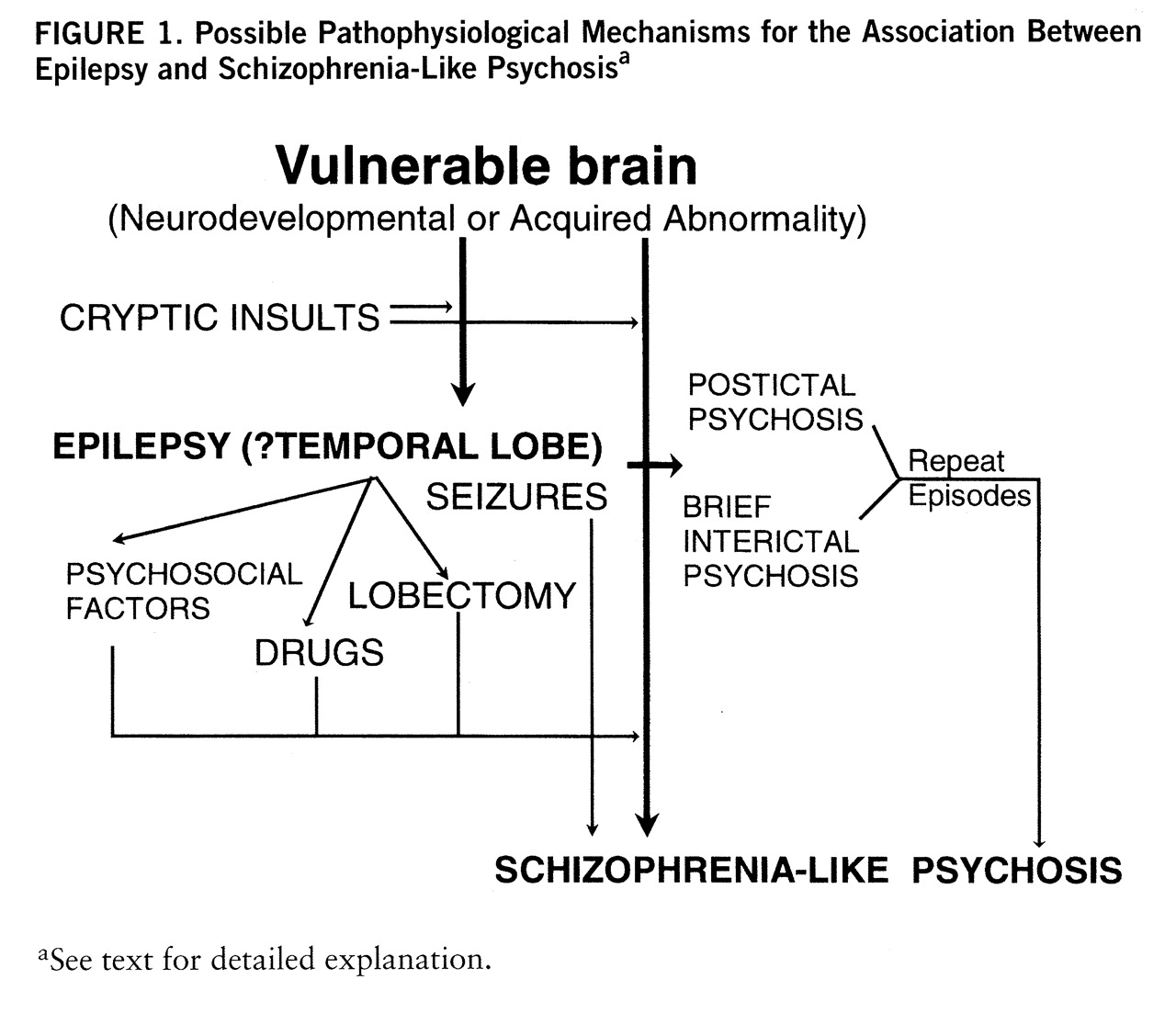

Possible Pathophysiological Mechanisms for Psychosis in Epilepsy

Discussion has centered broadly on two mechanisms: 1) the psychosis is due to the repeated electrical discharges, either directly or through the development of neurophysiological or neurochemical abnormalities, or 2) the epilepsy and psychosis share a common neuropathology that may be localized (emphasis on temporal lobe but also frontal lobe and the cerebellum) or widespread in the brain. Both mechanisms may be operative, the latter being primary and the former modifying the presentation, determining exacerbations and remissions, or being the proximate cause. The possible roles of psychological factors, neurotoxicity of anticonvulsant drugs, deficiencies (e.g., folic acid), and abnormal experiences seem to be of secondary importance.

Psychosis is a direct consequence of the epileptiform disturbance. I have previously referred to mechanisms by which seizures may directly result in ictal, postictal, and brief interictal psychoses: continuous subictal activity, homeostatic mechanisms that help reduce epileptic excitability, and neurochemical and neuroendocrine changes produced by the seizures. These explanations are inadequate for chronic schizophrenia-like psychosis even though they may account for some fluctuation of symptoms.

Kindling has been proposed as one possible mechanism for the occurrence of chronicity. Studies of behavioral and pharmacological kindling in animals, and the development of mirror foci, suggest that the potential exists for repetitive epileptiform discharges to facilitate subsequent propagation along specific pathways that may cause interictal disturbance. Electrical and pharmacological kindling of the ventral tegmentum and amygdaloid kindling by cocaine and apomorphine in the cat (

87) have been suggested as model psychoses. The long duration of epilepsy before the onset of psychosis, the frequency of the partial seizures, and the limbic origin of the seizures provide evidence for this hypothesis. Kindling may thus explain some aspects of the relationship between epilepsy and psychosis, especially the antagonism (

88), but there are limitations to the hypothesis: the relationship of the psychosis to seizures is variable in terms of age at onset, duration, and frequency; it is uncertain whether kindling can be permanent; patients usually have generalized seizures and widespread pathology; and kindling currently imputes the dopamine hypothesis of psychosis, support for which is inconsistent. Postlobectomy psychosis has been suggested to be a result of downstream kindling due to persistent ictal activity and perhaps decreased seizure frequency (

83). Delayed psychosis after right temporoparietal stroke has been reported in one series of eight patients, seven of whom developed seizures before the psychosis (

89).

Another mechanism by which frequent seizures may bring about chronic behavioral disturbance is the production of plastic regenerative changes affecting, in particular, the medial temporal lobes. It has been shown that stimulation of the hippocampus leads to an anomalous axonal sprouting from dentate granule cells before the development of seizures (

90). Expansion of glutamatergic presynaptic mossy fibers and an increase in perforated postsynaptic densities on granule cell dendrites have been demonstrated in temporal lobectomy specimens (

91), changes possibly produced by increased expression of messenger RNA for c-fos and NGF by recurrent limbic seizures. The aberrant regeneration and the resultant “miswiring,” alone or in combination with the underlying neuropathology, may be the underlying basis for chronic schizophrenia-like psychosis (see following section).

Both psychosis and epilepsy are symptomatic of an underlying neuropathological or physiological dysfunction. Two major possibilities have been suggested: 1) neuro~developmental abnormalities leading to cortical dysgenesis as the common factor and 2) diffuse brain damage causing both epilepsy and psychosis.

1. Cortical dysgenesis hypothesis. Neuropathological studies of temporal lobe epilepsy suggest that about two-thirds of the patients show hippocampal cell loss and sclerosis, particularly in the prosubiculum and CA1 regions, and a substantial proportion of temporal lobe epilepsy patients (

92) have other pathologies, in particular gliomas, hamartomas, and heterotopias. The presence of these alien tissue lesions suggests defective neuroembryogenesis. Patients with mesial sclerosis commonly have heterotopias, hippocampal neuronal loss of about 20%–50% (

92), and synaptic reorganization in the hippocampus. Veith (

93) reported heterotopias in 37% of temporal lobe epilepsy patients but only 4% of nonepileptic comparison subjects. Heterotopic abnormalities have also been described in primary generalized epilepsies (

94,

95). Cryptic insults such as childhood viruses, fever, or minor hypoxia may lead to synaptic reorganization in vulnerable brains, exacerbating the problem.

There is now considerable evidence that schizophrenia is associated with cortical maldevelopment (

96). More than a decade ago it was demonstrated that schizophrenic patients had a disorganization of the pyramidal cell layer (

97), which was thought to represent a problem in the migration of primitive neurons into the presumptive hippocampal plate. Heterotopias have been demonstrated in the brains of schizophrenic persons (

98), and there is also evidence for synaptic reorganization (

99). These disturbances either have a genetic basis or may be due to prenatal, perinatal, or early developmental insults.

If similar developmental abnormalities underlie both epilepsy and schizophrenia, it is not surprising that some epilepsy patients develop schizophrenia-like psychosis. The evidence that schizophrenia-like psychosis is more likely to develop in epileptic patients with developmental brain abnormalities (

77,

79) is consistent with this suggestion. That epilepsy and psychosis have different ages at onset may be due to different functional consequences of the abnormalities, depending on the stage of neurodevelopment. Epileptic activity may, in addition, exacerbate an underlying dysgenesis, setting the stage for psychosis.

2. Diffuse brain damage hypothesis. While there has been extensive neuropathological interest in the temporal lobe, there is evidence that brain abnormalities in the brains of schizophrenic subjects are widespread (

96). Most neuropathological studies of epilepsy and psychosis have been limited to the examination of resected temporal lobes. The studies by Stevens (

83) and Bruton et al. (

68) are exceptions, revealing excess pathology that was widespread and not dissimilar to some of the pathology reported for schizophrenia. These findings argue that schizophrenia-like psychosis may be related to degenerative or regenerative changes in the brain not directly related to the classic epileptic pathology.

3. Composite model. An attempt at a synthesis of the various hypotheses is presented in

figure 1. According to this view, epilepsy patients who develop chronic schizophrenia-like psychosis have a brain lesion that makes them vulnerable to psychosis. This lesion may be neurodevelopmental, leading to cortical dysgenesis, or be acquired through trauma, hypoxia, infection, etc. The abnormality may be widespread but is particularly likely to involve the limbic structures, leading to abnormalities of connectivity of these structures to their afferent and efferent projection regions. Since the development of medial temporal structures is asymmetric, it may explain some of the laterality data. The abnormality is likely to cause electrical storms in the limbic cortex, with seizures occurring at an early age. The occurrence of frank seizures or microseizures exacerbates the abnormality owing to kindling mechanisms or the regenerative changes involving axonal sprouting and synaptic reorganization. In due course these result in disruption of anatomically distributed functional systems and lead to schizophrenia-like psychosis, accounting for the “affinity” between epilepsy and schizophrenia-like psychosis. Seizures, either by the presence of continuous subictal activity or by their modulation of catecholamine and pre- and postsynaptic glutamatergic and GABAergic activity, modulate the expression of the psychosis or act as brakes, sometimes leading to the impression of antagonism. The picture is further complicated by long-term drug therapy, with its potential for neurotoxicity, and psychosocial factors related to epilepsy, a chroni~cally disabling and stigmatizing illness.