Fluvoxamine is a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) approved in the United States for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder and used worldwide for the treatment of a variety of psychiatric conditions. As with all SSRIs, side effects, such as sexual dysfunction, that are presumed to arise from centrally mediated mechanisms often emerge during fluvoxamine treatment. As a consequence, clinicians may discontinue medication for brief periods (“drug holidays”) to relieve these side effects. The rationale for this approach is based partly on what is known about the elimination of drug from plasma, but this may not correspond to the brain half-life of the drug. Abrupt discontinuation of SSRIs has more recently been identified with a withdrawal syndrome, particularly for the shorter half-life agents, that may also arise from centrally mediated mechanisms. The current study demonstrates that brain elimination pharmacokinetics can be systematically measured by using magnetic resonance spectroscopic techniques for the noninvasive, serial measurement of fluorinated psychotropic medications in the human brain (

1,

2). Better understanding of the brain pharmacokinetics of these medications may lead to a better understanding of the time course of clinical effects, both beneficial and adverse.

METHOD

Six consecutive subjects, all ending treatment with fluvoxamine for a psychiatric disorder, were recruited from the Center for Anxiety and Depression at the University of Washington for this study. The subjects gave written informed consent for

19F MRS and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies in a manner that was approved by the University of Washington Internal Review Board. The subjects were five men and one woman whose mean age was 48 years (SD=16) and who had had a minimum of 5 weeks on a constant daily dose of fluvoxamine. In our previous work, 5 weeks was shown to be sufficient to achieve steady-state concentration of fluvoxamine in the brain (

3). None of the subjects had a concurrent history of substance abuse. Four of the subjects were being treated with fluvoxamine for obsessive-compulsive disorder, one for panic attacks, and one for depression. Four subjects were stopping drug treatment because of an unsatisfactory response to the medicine or side effects, and two were stopping for trial periods without medication while in remission. The subjects were taking various doses ranging from 100 to 300 mg/day, as shown in

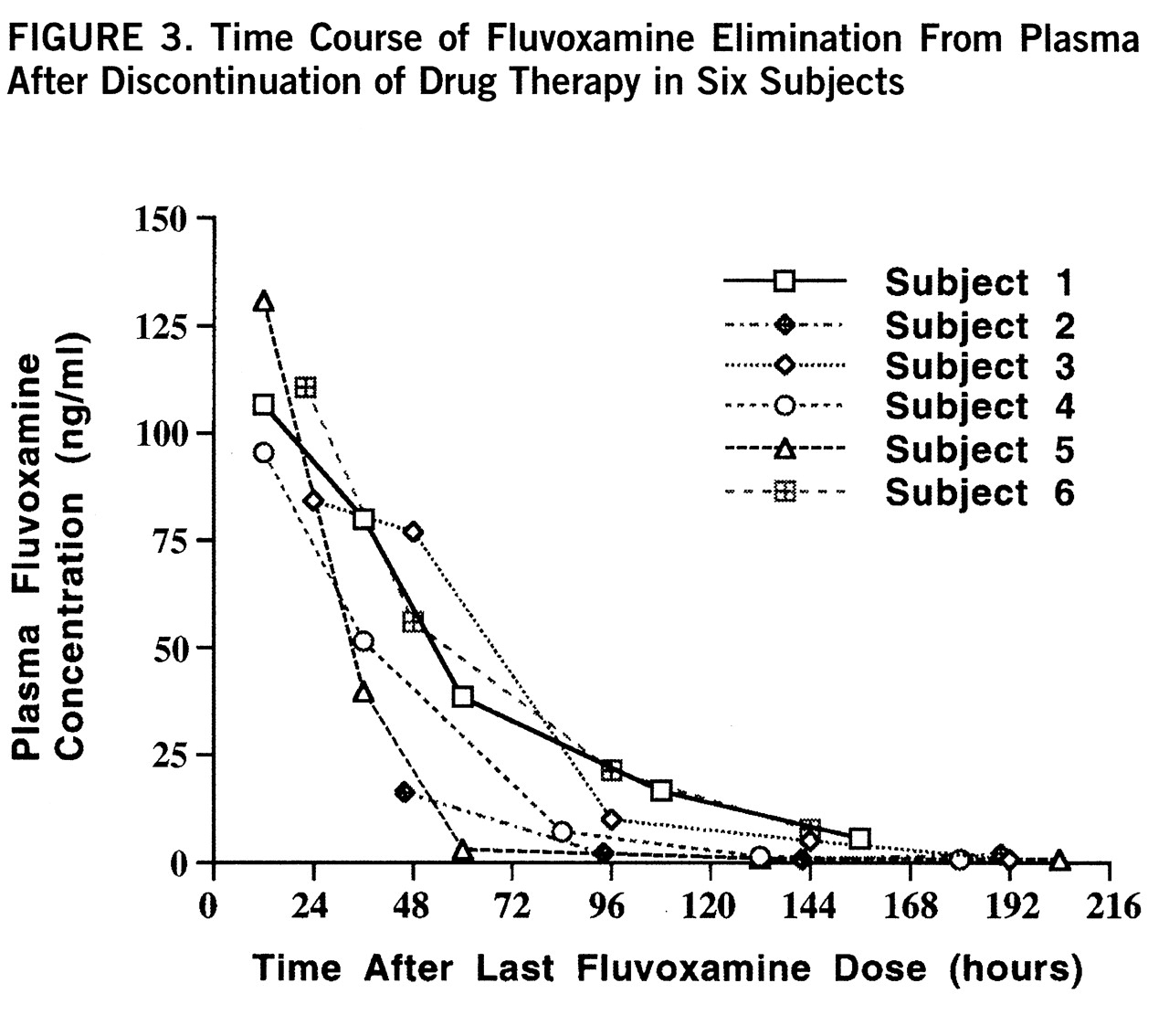

table 1.

MRI and MRS were performed with a GE Signa magnetic resonance scanner equipped with Genesis 5.4 software (GE Medical Systems, Milwaukee), a broad-band power amplifier, and a short-bore birdcage fluorine head coil. Details of the

19F MRS data acquisition system are expanded upon in our previous report (

3).

Following the last dose of fluvoxamine, serial

19F MRS scans were acquired over a range of 12–240 hours, at 24- or 48-hour intervals. Each scanning session consisted of determination of whole brain fluvoxamine concentration by MRS with a nonselective π/2 (90°) pulse and a TR of 1.0 seconds. The power for the π/2 pulse was determined by using a resistive loading device and sodium fluoride phantom designed to load the coil to 50 Ω, the approximate loading of an adult head. Signal quantification for each session was performed in relation to a coil loading device as previously detailed (

3). Whole blood samples were collected from the subjects at each time point, and fluvoxamine freebase plasma concentrations were determined by capillary gas chromatography with electron capture detection (unpublished method, Solvay Pharmaceuticals). Subjects were evaluated by a psychiatrist (S.R.D. or M.E.L.) at each spectroscopy session to ascertain any changes in clinical status.

The brain concentration curves for each subject were fitted with zero-, first-, and second-order kinetic functions to determine the appropriate model for drug elimination. The lowest-order model with acceptable residuals (R2>0.90) was considered to optimally describe the elimination data. The plasma concentration curves were fitted with a first-order kinetic model. All modeling and residual determinations were performed with the Levenburg-Marquardt nonlinear least squares algorithm. The half-life was computed from the fit of the model, and the area under the drug activity versus time curve (area under the curve) was computed by integration of the model function. Spearman's nonparametric statistical analysis was used to calculate correlation coefficients between the brain and plasma half-lives and dose and age. Spearman's test was used to avoid overprediction from outliers.

RESULTS

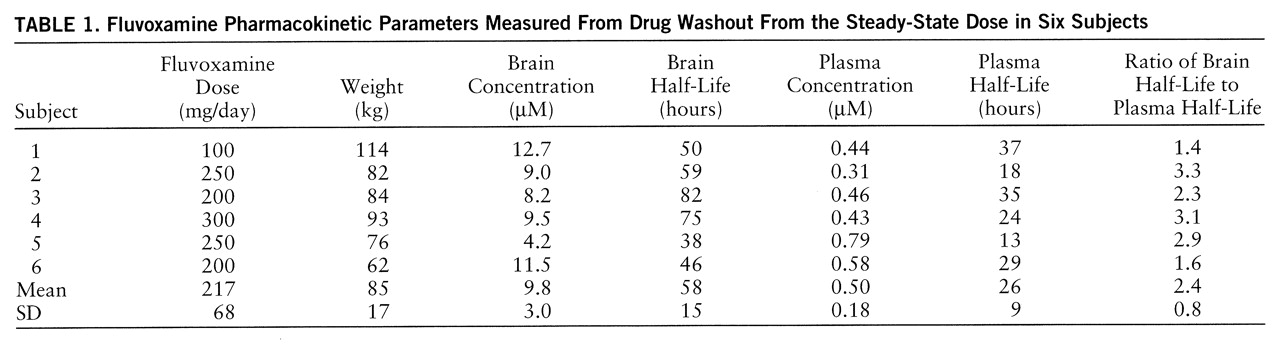

The subjects had readily quantifiable levels of brain fluvoxamine throughout the course of the study. The lowest brain level detected was 1.8 µM after 8 days without medication. The individual time course of elimination of fluvoxamine from the brain for each of the six subjects is shown in

figure 1. A first-order model for the washout was found to optimally fit the data with an R

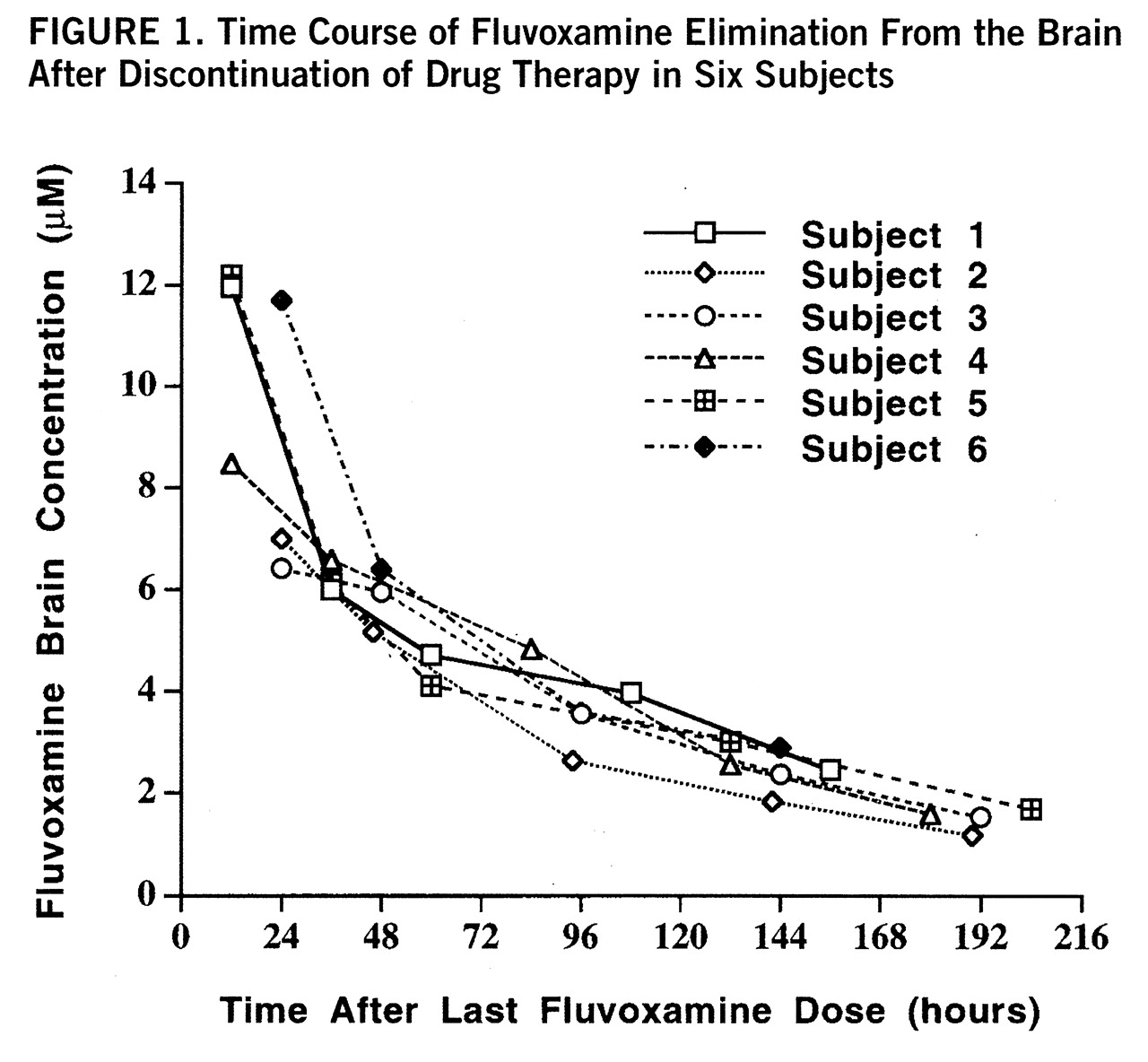

2 of 0.95 or better for each of the six subjects. The time course with fit of the model function is shown for one subject in

figure 2. Three model-dependent parameters were calculated for the subjects; the area under the curve was 911 µM·hours/liter (SD=120, N=6), the elimination half-life was 58 hours, and the exponential rate constant was 0.013 hour

–1 (SD=0.003, N=6). The results for each subject are shown in

table 1.

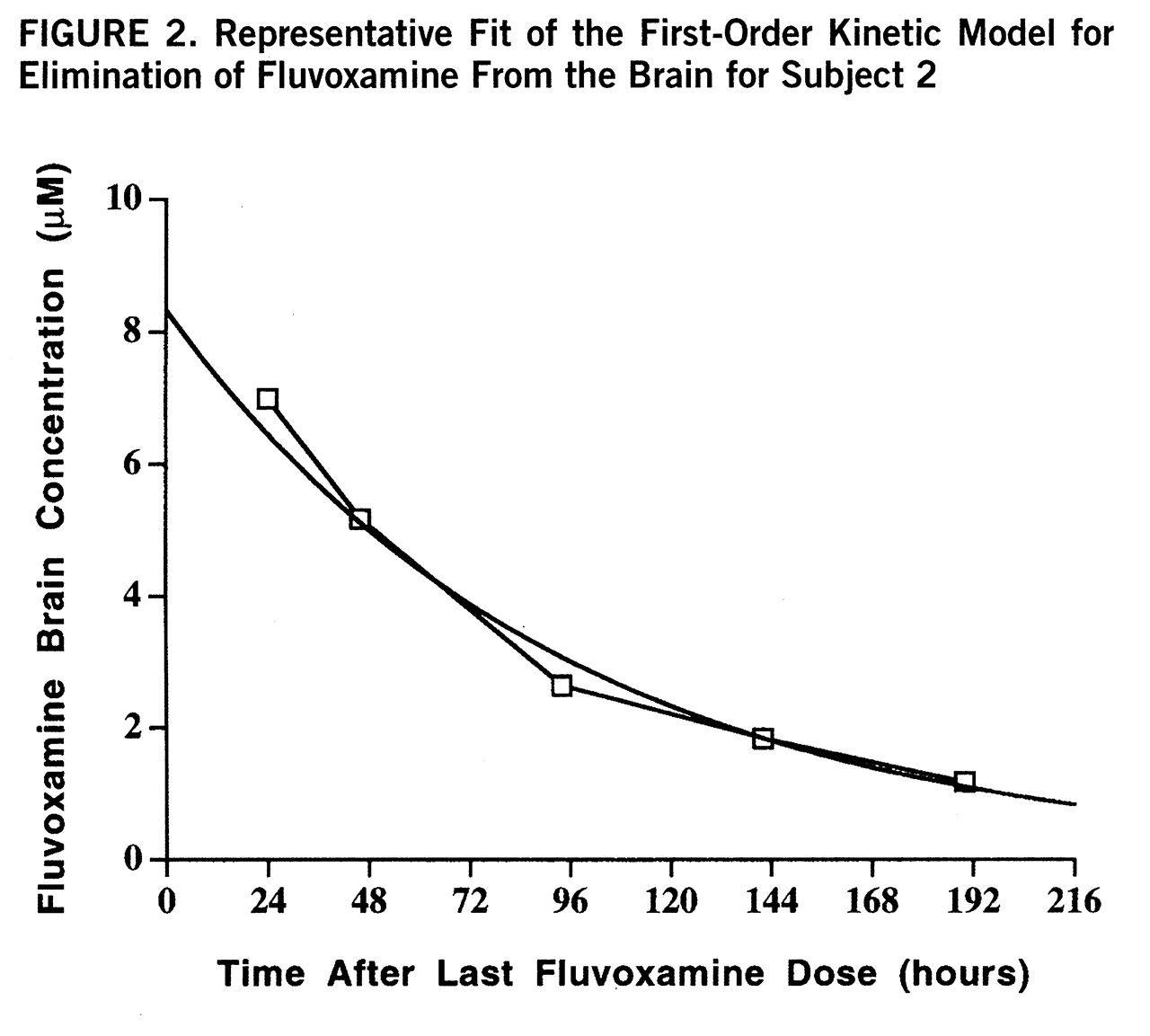

Plasma levels of fluvoxamine were also measured over the time course of the study and modeled by first-order kinetics with a minimum R

2 of 0.91. The individual time course of fluvoxamine elimination from plasma for each subject is shown in

figure 3. The plasma elimination half-life after drug discontinuation at steady state was 26 hours, with an exponential rate constant of 0.031 hour

–1 (SD=0.012, N=6). The steady-state plasma concentration was 0.50 µM. The brain elimination half-life was significantly longer than the plasma half-life as determined by independent t test (t=4.04, df=10, p<0.002). The mean ratio of each subject's brain half-life to plasma half-life was 2.4. These results are shown in

table 1.

We found no correlation between brain elimination half-life and daily dose of fluvoxamine (r=0.12, df=5, n.s.) or between plasma half-life and daily dose (r=–0.74, df=5, n.s.). Both brain and plasma elimination half-lives were uncorrelated with subjects' age (r=0.15, df=5, n.s., and r=0.43, df=5, n.s., respectively).

Three of the six subjects experienced mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms, consisting mainly of sweating, dizziness, headaches, and nausea. Two subjects began experiencing withdrawal symptoms at 72 hours and one at 120 hours. At the time of symptom onset, the average brain fluvoxamine concentration was 3.8 µM (SD=0.5) and was at 35% (SD=5%) of estimated peak steady-state brain fluvoxamine. For these subjects, withdrawal symptoms had resolved by the completion of the study (240 hours) and were not of serious clinical concern. No subject required reintroduction of fluvoxamine.

DISCUSSION

The major finding of this study was that fluvoxamine is eliminated from the brain with a half-life of 58 hours, on average 2.4 times longer than each individual's corresponding plasma half-life. Our determination of a plasma half-life of 26 hours is somewhat longer than published values of 14–22 hours (

4–

6), which likely reflects the difference between single-dose and steady-state half-life measurements (

7,

8). This dissociation of brain and plasma half-lives provides empirical evidence for understanding the efficacy of the clinical practice of brief drug holidays to reduce fluvoxamine-associated sexual dysfunction and may provide new insight into the time course for onset of withdrawal symptoms. In addition, the brain half-life of fluvoxamine is not correlated with daily dose, consistent with findings both from this study and from earlier studies that indicate clearance from plasma is also independent of drug concentration (

6). In this study, brain and plasma half-lives were not correlated with age (range=27 to 66 years), which corroborates earlier findings that the pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine in blood appear to be independent of age (

8).

A distinctive side effect of delayed orgasm or anorgasmia has been associated with the SSRIs (

9,

10). From studies evaluating the tricyclic antidepressants, these side effects are believed to be at least partly centrally mediated through a serotonergic mechanism (

11). The only study of which we are aware that systematically examined the clinical utility of brief drug holidays to decrease sexual side effects (

12) did not evaluate fluvoxamine. Since fluvoxamine has a brain half-life of about 58 hours, it appears that this agent is an ideal candidate for brief drug holidays of less than 3 days to provide acute symptomatic relief from sexual dysfunction. In contrast, clinical evaluation of fluoxetine suggests that brief drug holidays do not reduce sexual dysfunction (

12). Fluoxetine may not be an appropriate candidate for brief drug holidays because its protracted time course of uptake into the brain (

13) probably corresponds to a much longer brain elimination half-life than that of fluvoxamine. To our knowledge, brain half-life measurements for other psychotropic drugs, including fluoxetine, have not been reported.

Several reports in the literature have identified an SSRI withdrawal syndrome consisting of a constellation of symptoms that includes insomnia, confusion, dizziness, headaches, and gastrointestinal upset (

14–

16). Symptom onset is characteristically rapid and time-limited. Our observations that three of six subjects experienced mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms approximately 3–5 days after drug discontinuation are in keeping with these reports of fluvoxamine withdrawal which indicate that symptom onset typically occurs 3–5 days after abrupt drug cessation. Onset of withdrawal symptoms occurs in the time frame of one to two half-lives of fluvoxamine brain elimination, which corresponds to a decrease in brain fluvoxamine concentration to below half of its steady-state concentration. In contrast, by the time of onset of withdrawal symptoms, plasma drug levels have fallen by approximately three to five half-lives. We would expect a more rapid onset if decreasing fluvoxamine plasma concentrations were the primary mediating factor.

Drug toxicity and side effect profile are of particular concern for the elderly population because of potential changes in drug metabolism with age. Data from this study indicate that there is not a significant effect of age on fluvoxamine elimination from the brain over an age range of 27–66 years. This suggests that fluvoxamine is an appropriate medication choice for older individuals. However, further study is needed to confirm whether these findings extend to higher age ranges.

The elimination curves of brain fluvoxamine were fitted with zero-, first-, and second-order model functions to determine the optimal order. The order of the kinetic model defines the functional relationship between the rate of change of drug concentration in the brain and the concentration of drug in the brain. The goodness of fit for the model functions was judged on the basis of the residuals of nonlinear least squares fitting. In this study, fluvoxamine brain elimination was optimally modeled by a first-order kinetic function for each subject (R2>0.95). The first-order model is derived from assuming a linear relationship between the rate of change of concentration of brain fluvoxamine and the concentration of fluvoxamine in the brain and is given by the equation

Cf(t)=Cfo exp(–0.693t/t1/2),

where Cf(t) is the concentration of fluvoxamine at a time t, Cfo is the steady-state concentration before cessation of drug therapy (t=0), and t1/2 is the biological half-life. Time is measured in hours, with the cessation of drug treatment as the starting point (t=0). The elimination rate constant, kelim, was obtained from the relation kelim=0.693/t1/2. The area under the curve was computed from the integral of the model from time zero to infinity: AUC=Cfo/kelim. The area under the curve is more accurately determined from the parameter estimation than from direct numerical integration of the washout data, because the former is less sensitive to noise and does not suffer from a truncation artifact.

The goodness of fit of the first-order kinetic model to the washout data indicates that elimination of fluvoxamine from the brain was highly linear. The term “linear” is somewhat confusing, as the actual curve follows exponential decay, but the underlying model assumes a linear dependence between the rate of elimination of fluvoxamine from the brain and the concentration of fluvoxamine in the brain. In contrast, the elimination of fluvoxamine from plasma has been reported to be strongly nonlinear (

5,

6). This finding may have important implications for the distribution of fluvoxamine into the body tissues and implies that multicompartmental kinetics are required to explain the behavior of the drug.

Additional insight into the brain pharmacokinetics and disposition of fluvoxamine is gained through determining the area under the curve for brain concentration versus time. As discussed in our previous report (

3), the area under the curve used in classical pharmacokinetics, which derives from a single bolus injection of drug, is not available for fluvoxamine in the brain, since single doses at tolerable levels do not yield sufficient brain concentration for measurement at the current limits of

19F MRS technology. This study provides a way to estimate the area under the curve from the elimination of drug after cessation of therapy at brain steady state. Future work in this laboratory will involve using this estimate of the area under the curve with the development of new mathematical methods to estimate the volume of distribution and clearance of fluvoxamine from the brain.

There are some important limitations to a study of this type. The brain concentration of fluvoxamine as determined by

19F MRS can include contributions from its metabolites, which are known to be pharmacologically inactive (

17). This factor could lead to an overestimation of the parent compound concentration in brain. In addition, since the metabolites are presumably cleared from the brain with a different time course, this could introduce systematic error in the determination of brain elimination half-life. However, the residuals of the fits indicate accurate model estimation, suggesting that the metabolites are not present in sufficiently high concentrations to substantially effect brain half-life determination. Although, the pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine metabolites have not been systematically investigated, there are theoretical considerations to support the assumption that metabolites do not substantially contribute to brain measurements of fluvoxamine. The most abundant fluvoxamine metabolites (fluvoxamine acid, acetylated fluvoxamine acid, and fluvoxethanol) are highly polar and therefore unlikely to diffuse back into the brain after metabolism in the liver (

17). This implies that the metabolites are unlikely to be present in the brain at high-enough concentrations to substantially alter the determination of the half-life of the parent compound.

A second limitation may arise from the likelihood that brain fluvoxamine exists in both bound and free states. The bound pool of fluvoxamine, composed of drug associated with specific receptors and/or nonspecific proteins, would not be detectable by

19F MRS. The

19F MRS visible pool is primarily made up of the intra- and extracellular free pool of fluvoxamine. This could lead to an underestimate of the concentration of drug in the brain. Studies of fluorinated psychotropic compounds have demonstrated a range of

19F MRS visibility for these drugs. An autopsy study of fluoxetine indicated that a substantial fraction of the drug is not detectable by

19F MRS in the human brain (

18), in contrast to work showing good agreement between

19F MRS and gas chromatography quantification of dexfenfluramine in rhesus monkey brain (

19). Although it is not known where fluvoxamine falls on this continuum, its similarity in chemical structure to fluoxetine would suggest that there is a substantial bound fraction. In addition, if the bound pool becomes saturated at clinical doses, a more complex model would be needed to fit the washout data. Better time resolution in the first hours after drug discontinuation may help address this latter issue.

To summarize, the pharmacokinetics of brain fluvoxamine elimination following abrupt drug discontinuation can be characterized with the use of 19F MRS. This study indicates that fluvoxamine is eliminated from the brain at a slower rate than that of drug elimination from plasma. Measuring brain elimination half-life allows a better understanding of the clinical course of withdrawal symptom onset and provides a rationale for the use of drug holidays to alleviate targeted side effects such as sexual dysfunction. In addition, this study raises the possibility of determining pharmacokinetic parameters relating to drug disposition, such as brain volume of distribution, which have not been previously reported because of the difficulties of sampling drug concentrations in the brain. Further 19F MRS studies of fluorinated psychotropic compounds will expand upon these efforts toward a more meaningful pharmacokinetic framework in which to evaluate the clinical course of drug therapy than is currently available from traditional plasma pharmacokinetic studies.