Depression is one of the most frequently occurring psychiatric syndromes among older adults. The concept of depression includes a continuum of symptoms ranging from dysphoria, which may affect almost everyone from time to time, to a diagnosed depressive disorder (

1). Several factors are associated with depression in old age, including disabilities in daily living, lack of social support, institutionalization, and declining health (

2–

7). Advanced age also results in an increase in lifetime risk of exposure to stressful life events and personal losses (

8). Moreover, there is an increase in the occurrence of depression in age-related neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease, vascular dementia, and Parkinson's disease (

9).

Relatively little is known about the incidence of depression in older populations because most community studies have not had large enough samples to generate incidence data (

10). Among those who have tried, incidence rates have varied markedly across studies (

11). In a 1994 review (

12), Kanowski reported that the incidence of depression was approximately 2/1,000 per year in the total population of adults. A study from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area program that assessed depressive symptoms before the first onset of major depression in a community sample (

8) estimated that the incidence of major depression was 9/1,000 per year for individuals above 64 years of age.

There is some evidence that the development of major depression in old age is a process that can take many years. For example, Henderson and Jorm (

13) noted an elevation in depressive symptoms in individuals who were diagnosed more than 3 years later. However, they did not examine which specific symptoms were elevated among those who were later diagnosed as having major depression. In 1996, KivelÄ et al. (

6) observed that Finnish subjects who were diagnosed as depressed after a 5-year follow-up had exhibited elevated appetite disturbance, psychomotor disturbance, and dysphoria at baseline.

The present study sought to identify preclinical markers of major depression in very old (≥75 years) subjects, 3 years before they were clinically diagnosed. We examined potential early markers for major depression in terms of the signs and symptoms of this disorder, based on DSM-III-R criteria. We were interested in the role of both symptom presence and symptom severity in the incidence of major depression. A second focus was whether cognitive impairment is a preclinical marker of depression in the very old. Depressed individuals typically perform more poorly on cognitive tests than those who are nondepressed (

14–

16), but, to our knowledge, this issue has not been examined in subjects who are at risk for developing depression.

The study participants came from a population-based longitudinal investigation of very old adults residing in Stockholm. The study group is unique in that little is known about incidence of major depression among very old adults because most related studies have focused on younger groups of individuals (

8,

10). In addition, the study could generate novel longitudinal information, in terms of preclinical markers and the natural course of major depression in very old adults, because most related studies have been based on cross-sectional comparisons or have included only clinical samples (

2).

METHOD

Subjects

The original subjects were drawn from all the inhabitants 75 years old and older in the Kungsholmen parish of Stockholm who were included in a population survey on aging and dementia (N=2,368). A detailed description of the subjects and the methods used has been provided elsewhere (

17). Briefly, during the initial screening of the whole study group (phase 1), 1,810 subjects were given a questionnaire that included the Mini-Mental State (

18) to detect suspected cases of dementia. Approximately 3 months after this screening, 314 individuals with cognitive impairment, as determined by Mini-Mental State scores of 24 or lower, and a random sample of 354 comparison subjects with Mini-Mental State scores higher than 24 were examined (phase 2). An extensive medical, neurological, psychiatric, and cognitive protocol was used to examine these 668 individuals. At retest approximately 3 years later (mean=2.98 years) (phase 3), subjects from phase 2 were invited to participate in a follow-up assessment that used the same protocol used in phase 2. The Kungsholmen project has been approved by the ethics committee of the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants after details of the procedure had been fully explained.

The original baseline study group for the current study consisted of the 398 adults who did not receive a dementia diagnosis in phase 2. Because the goal of the study was to examine preclinical markers of depression in normal aging, we excluded subjects with baseline Mini-Mental State scores of 24 or lower (N=46); subjects with psychiatric illness (e.g., depression, schizophrenia) (N=20); those with a history of stroke (N=17); and those with Parkinson's disease (N=3). Forty-two subjects were eliminated because they were diagnosed as having dementia at follow-up. The diagnostic criteria and procedure used to reach the diagnosis of dementia have been described in detail elsewhere (

19). Of the remaining 270 participants, 193 were alive and available for study at follow-up (53 had died over the follow-up interval, and 24 had dropped out of the study). Because data were missing for eight subjects, the final study group at follow-up consisted of 185 subjects: 175 individuals who were not depressed and 10 individuals who were diagnosed with major depression. None of the eight subjects with missing data were diagnosed as having major depression. Thus, the annual incidence rate of major depression was calculated to be 17/1,000.

At baseline assessment, depression was diagnosed by using DSM-III-R criteria for major depression (i.e., criterion A of major depressive episode). At 3-year follow-up, the diagnosis of depression was determined by using DSM-IV criteria A, B, and E. Criterion C was excluded because of difficulties in judging that the symptoms caused clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning in this very elderly group. Similarly, criterion D was not used because of difficulties in judging the etiology of depression in this group. In addition, for the 10 subjects who were depressed at follow-up, information was gathered at follow-up concerning previous psychiatric disorders, contact with health care professionals for psychiatric symptoms, and antidepressant drug treatment.

Measures

Psychiatric signs and symptoms. Information regarding psychiatric symptoms was derived from a structured interview administered by physicians using the Comprehensive Psychopathological Rating Scale (

20). The physicians attended regular meetings in order to obtain accuracy in their ratings. Each question was rated on a scale ranging from 0 to 6. According to established criteria (

20), a score of 2 or higher is indicative of pathology. Reported symptoms in the present study are those stated in DSM-IV for major depressive episode.

To examine both presence and severity of depressive symptoms, two sets of variables were created. When analyzing the presence of a symptom, we changed a score of 1 or lower to 0 (i.e., absence of symptom), but because a score of 2 or higher indicated presence of a symptom, we changed it to 1. When focusing on the severity of symptoms, we used the original scale, which ranged from 0 to 6.

Background variables. In addition to age, sex, and number of years of education, information regarding the subject's levels of global cognitive functioning, functional ability, and somatic disorders was gathered.

Global cognitive level was indexed by using Mini-Mental State (

18) scores. The Swedish version of the test was administered according to standardized procedures, and the maximum total score was 30. In addition to computing the total score, we computed 11 individual item scores: orientation to time, orientation to place, immediate word recall, serial sevens, delayed word recall, naming, repetition, following commands, reading, writing, and design copy.

Functional ability was measured by using the Katz Index of Activities of Daily Living (

21). This measure inquires about the person's ability to perform such tasks as bathing, dressing, going to the toilet, transferring, continence, and feeding. The score ranges from 1 (independent) to 7 (dependent).

Finally, participants were asked about the presence of 11 somatic disorders: diabetes, high blood pressure, cardiac insufficiency, angina pectoris, arthritis/rheumatism, ischemic attacks, autoimmune disease, cataract, glaucoma, cancer, and chronic pain. A composite score for the 11 disorders was used in this study.

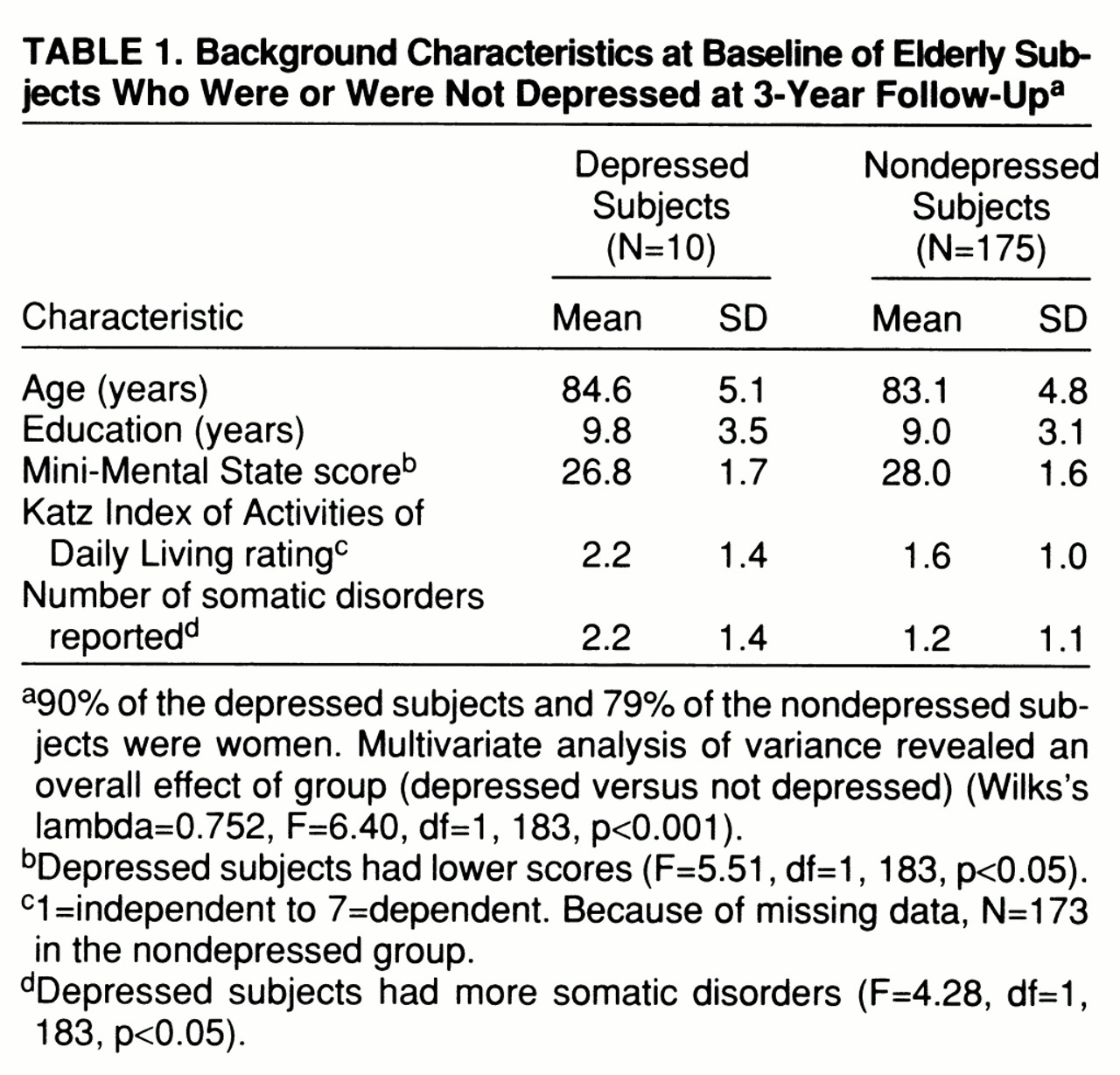

Demographic characteristics of the subjects are shown in

table 1. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) revealed an overall effect of group (depressed versus not depressed). Univariate analyses of variance showed that the groups did not differ in terms of age, number of years of education, sex distribution, or functional ability (p>0.10), although the subjects who were depressed at follow-up had lower Mini-Mental State scores and a higher number of somatic disorders than the nondepressed subjects at baseline (

table 1). The proportion of women is representative for this age group in Stockholm (

22).

RESULTS

The main data analysis consisted of two parts. First, we examined baseline differences between the subjects who were or were not depressed at follow-up in terms of presence and severity of depressive symptoms. Second, we examined differences in baseline cognitive functioning as a function of group (depressed versus not depressed).

As noted, the subjects who were depressed at follow-up differed from those who were not depressed at follow-up in terms of the occurrence of somatic disorders at baseline. Because somatic disorders may be associated with elevated depressive symptoms, we used this variable as a covariate in our analyses. However, the outcome remained unchanged with or without the covariate, and the results reported throughout are from the more straightforward analyses without the covariate.

Depressive Symptoms

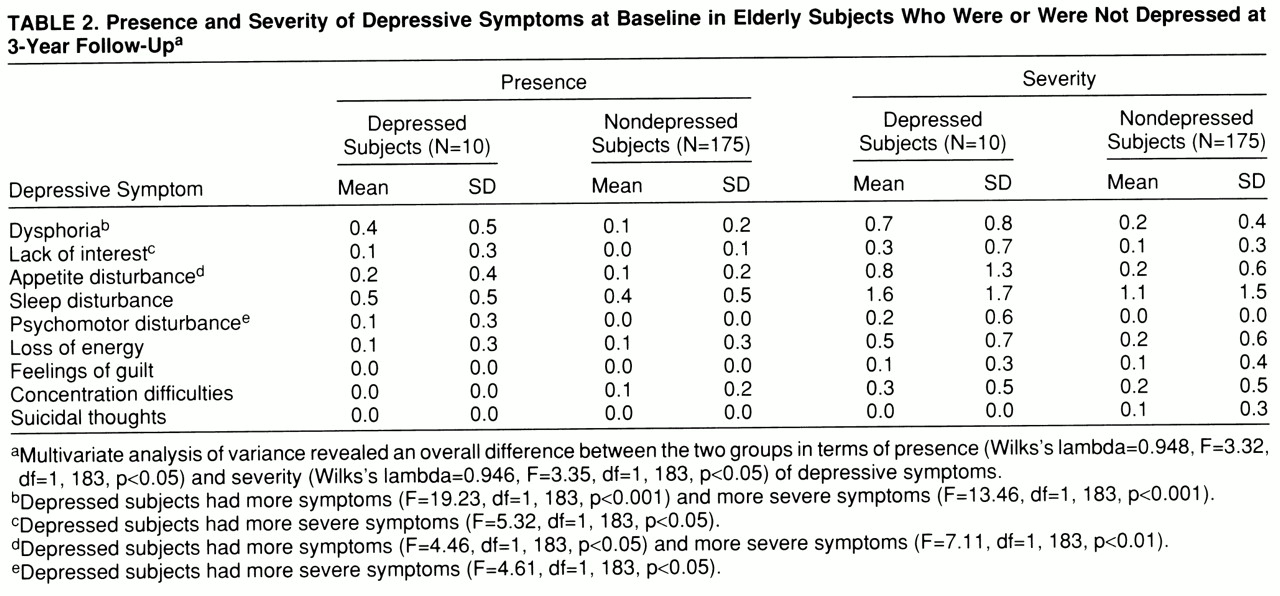

Table 2 displays the results for presence and severity of the depressive symptoms at baseline. There was an overall difference between the two groups in terms of presence of depressive symptoms at baseline. Specifically, the 10 subjects who were depressed at follow-up had more symptoms of dysphoria and appetite disturbance at baseline than did the subjects who were not depressed at follow-up.

The overall analyses of the severity of the depressive symptoms revealed that the subjects who were depressed at follow-up also had more severe symptoms at baseline (

table 2). Group differences in severity were observed for dysphoria, appetite disturbance, lack of interest, and psychomotor disturbance.

Cognitive Functioning

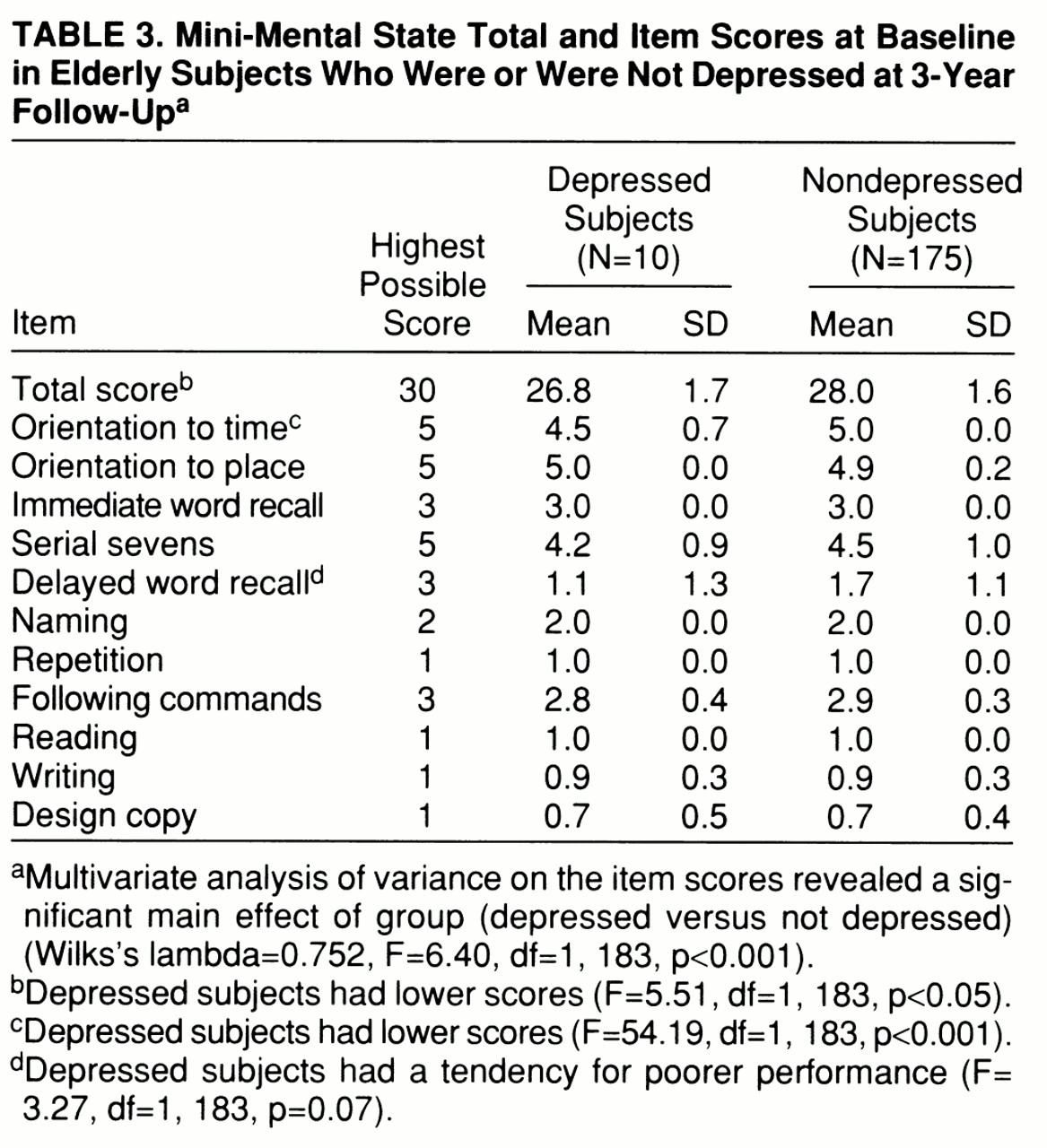

Cognitive performance of the subjects who were or were not depressed at follow-up is presented in

table 3. In the analysis of the background characteristics, the subjects who were depressed at follow-up had lower scores on the Mini-Mental State than those who were not depressed (

table 3). To determine the source of their poorer performance, we conducted a MANOVA on the item scores from the Mini-Mental State. Confirming the results obtained with the total score, there was a main effect of group (depressed versus not depressed) (

table 3). The subjects who were depressed at follow-up scored lower on orientation to time and had a tendency for poorer performance in delayed word recall.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the occurrence of baseline depressive symptoms and cognitive impairment in individuals who were or were not determined to be clinically depressed after a 3-year follow-up interval.

Our results revealed that the subjects who were depressed at follow-up differed preclinically from those who were not depressed at follow-up in terms of both presence and severity of symptoms. Specifically, dysphoria and appetite disturbance were more evident and severe among the depressed subjects, and they also experienced more severe lack of interest and psychomotor disturbance than their nondepressed counterparts. Therefore, to obtain an accurate portrayal of early harbingers of major depression in old age, it may be important to focus on both the presence and severity of depressive symptoms, something that previous studies have failed to do. However, because the absolute values for symptom presence and severity were relatively low at baseline for the subjects who later became depressed, the clinical significance of the elevated symptoms for individual subjects remains unclear.

Although we observed preclinical effects with regard to depressive symptoms of both an emotional (e.g., dysphoria) and motivational (e.g., lack of interest) nature, it is important to note that for several symptoms the depressed and nondepressed groups were indistinguishable. For example, the groups did not differ with regard to feelings of guilt or suicidal thoughts. This finding is consistent with other research reporting that depressed older outpatients showed less guilt feelings than their younger counterparts (

10,

23). Thus, symptoms such as guilt feelings and suicidal thoughts may occur later in the course of old-age depression.

Our results indicating a relatively long preclinical phase of major depression in old age are in agreement with other reports that have focused on young-old adults (

5,

6). Results demonstrating a long preclinical phase of major depression in older adults may be partly due to the fact that recognition of old-age depression is more difficult than recognition of depression in earlier life. Elderly individuals may report somatic complaints rather than depressed mood (

2). Because depression in old age is related to social, developmental, and biological factors, the heterogeneity in the causes of depressive symptoms also makes it difficult to recognize and understand the natural history of late-life depression (

2).

Our findings regarding the development of depression in old age stand in contrast to the relatively short clinical onset expected in younger adults. DSM-IV suggests that “symptoms of a Major Depressive Episode usually develop over days to weeks” (p. 325). In the current study, we found evidence that elevated symptoms were present up to 3 years before the diagnosis of depression was rendered. Thus, in older individuals, the course of depression may be more chronic than acute in nature. Although DSM-IV suggests that symptoms may persist “for months to years” (p. 325), the lengthy development of depression may be much more common among very old adults.

Having said that, we feel that an inherent problem in the majority of studies on preclinical indicators of disease (e.g., depression, dementia) should be acknowledged; namely, the uncertainty concerning the exact time of disease onset. Specifically, how can we assure that clinical depression was not present relatively soon after the initial assessment among the subjects determined to be depressed at follow-up? If this were the case, it would certainly call into question the view that old-age depression may have a relatively long preclinical period. None of the subjects who were depressed at follow-up had a history of previous depression or any other psychiatric disorder, none had been in contact with primary or special care for psychiatric treatment during the retest interval, and none was receiving antidepressant medication at follow-up assessment. In addition, as noted, these subjects had relatively few symptoms at baseline. Collectively, these observations suggest that the probability that we observed emergence and persistence of depression rather than a long preclinical phase is rather low.

We also examined potential differences in cognitive performance between the subjects who were or were not depressed at follow-up. The results indicate that subjects who were depressed performed more poorly on Mini-Mental State total score and on the orientation to time item. The source of the impairment in orientation to time may be related to apathy or lack of motivation to give a correct answer. Compared with the nondepressed subjects, those who were depressed at follow-up were more affected in terms of lack of interest, which may be a contributing factor for recalling less information about their everyday life. Responding correctly to these items may require more intrinsic motivation than items with more structured requirements (e.g., design copy). It is important to note that the present study examined individuals in a preclinical state of major depression. Even in studies using clinically depressed subjects, there have been difficulties in finding distinct patterns of cognitive deficits (

24–

26). Thus, given that we examined preclinical depression, it is not surprising that the cognitive impairments observed were relatively minor.

Although our study is informative regarding preclinical markers of depression, there is one limitation that must be acknowledged. The relatively small number of subjects who were depressed at follow-up (N=10) affects the power to detect reliable relationships. However, this small number is not unexpected given the relatively low rates of incidence for this disorder (

8). In the present study the incidence rate was 17/1,000, compared with incidence rates varying from 2/1,000 to 9/1,000 in other studies (

10,

12).

In summary, the results of our study indicate that there are preclinical markers for people who will become depressed after a 3-year interval. In particular, older adults who were depressed at follow-up reported at baseline a greater presence and severity of dysphoria and appetite disturbance, as well as more severe psychomotor disturbance and lack of interest than did individuals who remained nondepressed. In general, the results suggest that major depression has a more chronic nature in very old age. They also suggest that standard diagnostic instruments (i.e., DSM-III-R, DSM-IV) may have to take this into account when describing the course of major depression in old age.