Limitations of the Study

This study has several limitations. First, standard errors were calculated under the assumption that all observations were independent, which was not true in every case because some studies assessed subjects at repeated time points. When such data were available, we included all data points in the interest of using all available information. Our estimates of weight change with use of the weighted least squares method remain accurate (i.e., unbiased), but their standard errors may be too small. Ordinarily, one would take this dependency into account through the use of generalized least squares estimation

(26). Unfortunately, generalized least squares implementation requires knowledge of the covariance structure among the observations, and this information was not available. Therefore, the standard errors presented here and the significance levels based on them may, in some cases, be biased. To estimate the plausible degree of this bias, we assumed that all dependent observations had a correlation as high as 0.90 and conducted the fixed effects regression analyses through generalized least squares. The largest putative change in standard error for any drug occurred with chlorpromazine and was 59%. For no other drug did the increase in estimated standard error exceed 4%. Thus, this sensitivity analysis suggests that our standard errors are unlikely to have been underestimated to any substantial degree.

A second limitation concerns our inability to examine the extent to which weight change with antipsychotic drugs varied as a function of patients’ characteristics, such as age, sex, and initial body mass index. Unfortunately, the limited information presented in each study on the distributions of age, sex, and starting body mass index and the limited number of studies available for each drug precluded inclusion of terms for such patient characteristics in the metaregressions.

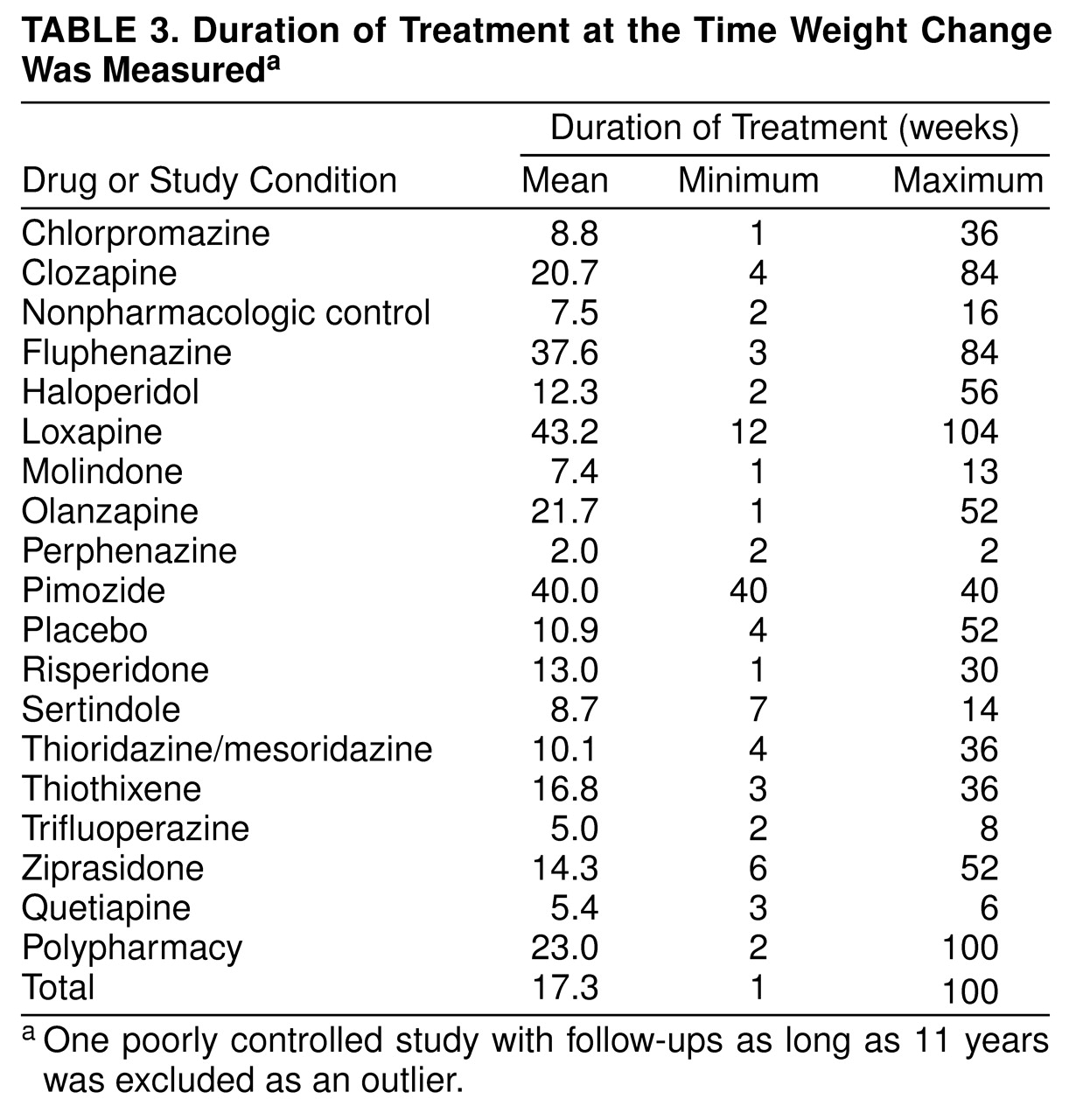

A third limitation is that for most drugs, insufficient information was available to provide precise estimates of weight change when patients were on the drug for extended periods of time, such as 6 months or more. Although we initially attempted to calculate such estimates, this frequently required extrapolations outside the observed range of data, and the resulting estimates were often extremely imprecise (i.e., had very large standard errors).

Strengths of the Study

To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive literature synthesis on antipsychotic-induced weight gain to date. Although it is plausible that some studies assessing the effect of antipsychotic medications on body weight were not discovered by our literature search, our procedures kept this to a minimum. We conducted a thorough search of the electronic literature and made efforts to access undetected literature through the “Invisible College” and formal contacts with pharmaceutical companies. Moreover, we conducted electronic searches of databases that also include unpublished literature, such as Dissertation Abstracts International and PsychINFO.

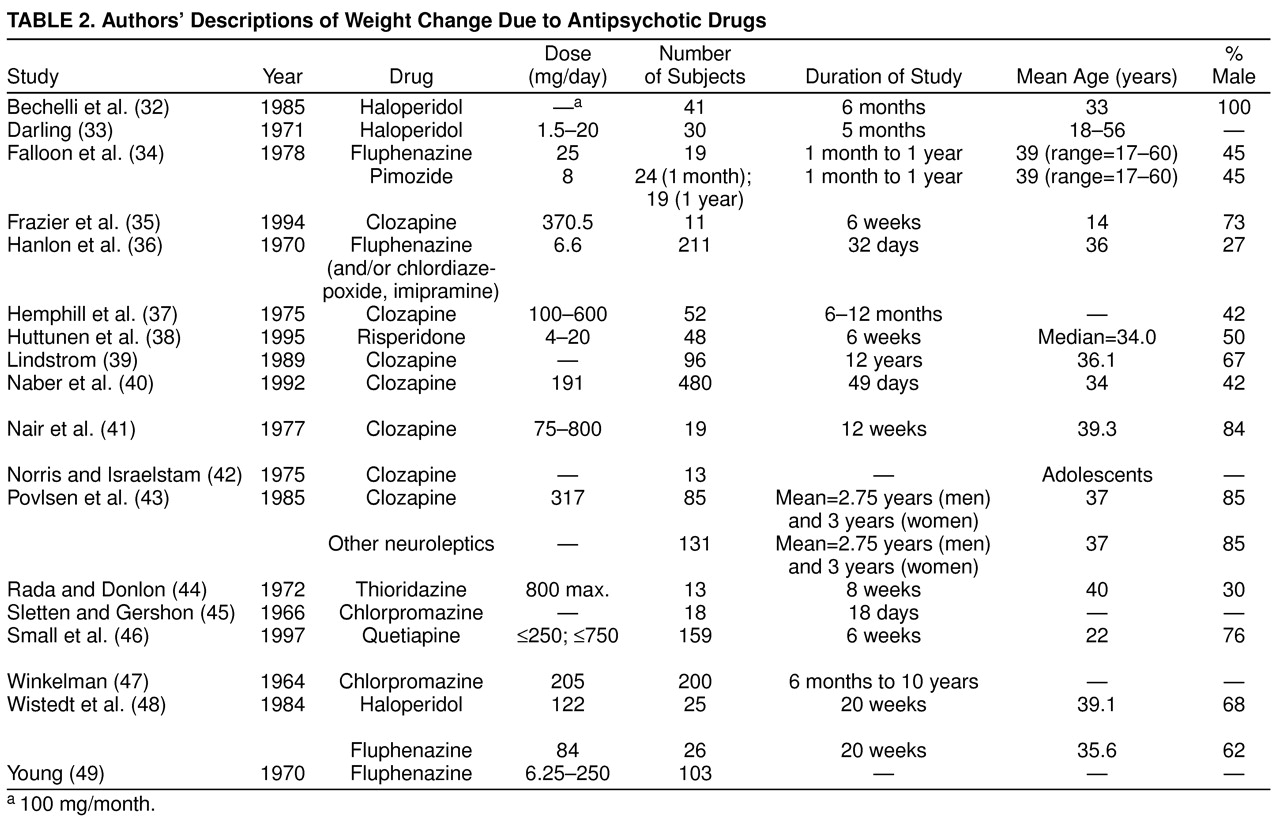

A common problem in meta-analysis is inadequate and incomplete reporting of key information in the primary articles. We attempted to minimize the impact of such incomplete reporting by contacting authors when feasible. Moreover, for studies that did not yield sufficient information to be included in the formal quantitative synthesis, we still attempted to extract whatever information was available in these reports and provide that in a structured verbal overview (

Table 2).

Our literature retrieval procedures also maximized the chances of obtaining relevant unpublished data. Publication bias is a commonly acknowledged problem in applied research. This problem confronts all literature reviewers, whether they conduct formal meta-analyses or not. We believe our efforts were quite strong in this regard and therefore should serve to minimize publication bias.

Clinical Implications

In the early days of chlorpromazine pharmacotherapy, Planansky and Heilizer

(61) reported that weight gain was associated with symptom improvement, and weight loss was associated with symptom deterioration. The subsequent availability of multiple antipsychotic medications has led to the observation that weight gain is a common side effect of antipsychotic treatment. There is some conjecture that the drugs which cause the most weight gain are the most effective. However, results are inconsistent and equivocal

(58,

62–

65), and further research is needed on this question.

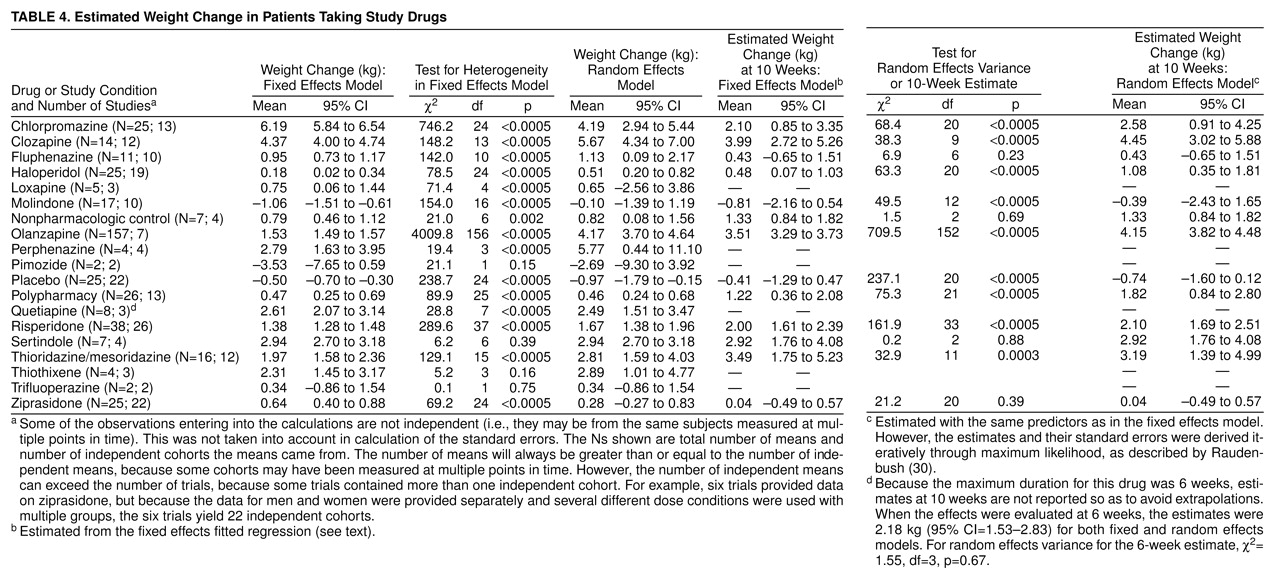

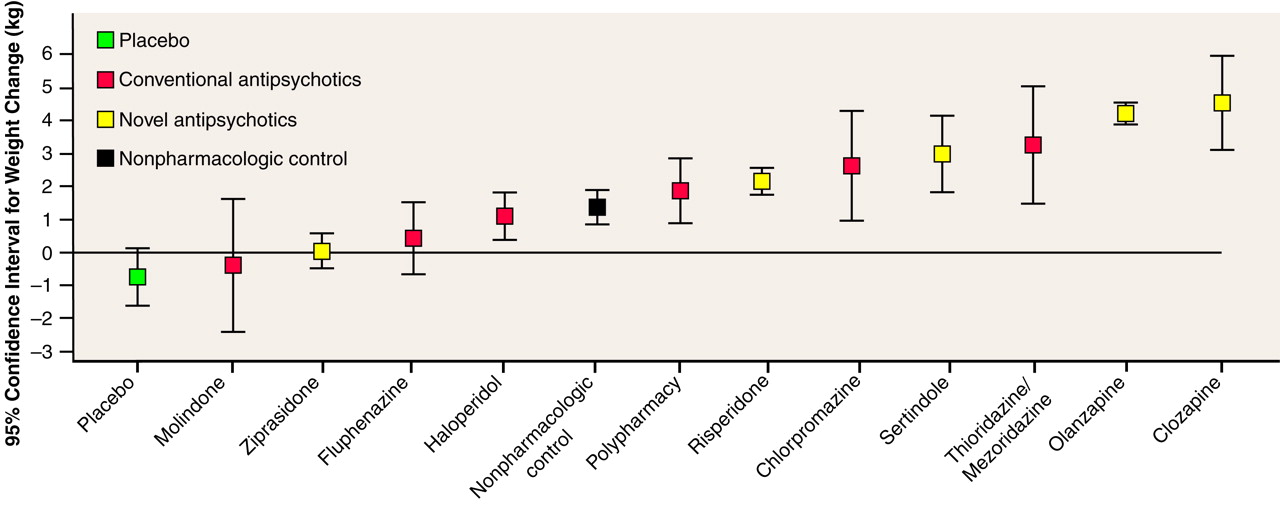

How clinically meaningful are these degrees of weight gain? Some compounds were estimated to produce close to a 5-kg weight gain at 10 weeks. Furthermore, the shorter-term controlled studies usually included data on all subjects, whereas long-term use was usually restricted to individuals showing a positive therapeutic response to the drug. If therapeutic response and weight gain are correlated (which may or may not be true), then this would imply that the 10-week weight gain may be higher than we have estimated. On the basis of the compounds for which longer-term data were available (chlorpromazine, clozapine, and olanzapine), it seems clear that although weight gain might reach a plateau after a certain period (e.g., for olanzapine, after 4–5 months), total weight gain will still be much larger after periods longer than 10 weeks. Thus, weight gains far in excess of 5 kg may be seen in patients on long-term therapy. However, even a weight gain of 5 kg will represent a weight gain of more than 5% of initial body weight for the majority of individuals. To place this in perspective, it is useful to consider that a number of authoritative bodies, such as the Institute of Medicine

(66), have suggested that weight losses of as little as 5% in obese individuals can result in clinically meaningful reductions in morbidity and risk of early mortality. It might be plausible, then, to expect that increases in body weight of as much as 5% would result in corresponding increases in morbidity and risk of early mortality.

Although the literature assessing the effects of weight gain on “hard” end points reveals a complex set of relations and modifiers, certain general conclusions can be drawn. For end points such as mortality

(67,

68), incidence of cancer

(69,

70), cardiovascular disease

(71,

72), and diabetes

(73), when factors such as smoking are accounted for, it appears that weight gains of 5% or greater during the adult lifespan are associated with important increases in risks. This is especially true for individuals who are overweight to begin with. Finally, although results are clearly preliminary, emerging data suggest that the drugs causing weight gain (i.e., clozapine and olanzapine) may, perhaps as a result, also be causing type II diabetes

(74–

77). Clearly, then, antipsychotics can induce medically meaningful degrees of weight gain.

Weight gain induced by antipsychotic drugs may also discourage patients from reliably taking their medication. This would, in turn, increase the likelihood of relapse. Although we are aware of no data that would allow precise quantification of the impact of weight gain on compliance with medication, we have observed that a number of patients complain of weight gain and occasionally report it as a reason for noncompliance. On the other hand, in studies conducted with olanzapine, Tollefson et al.

(78) and Beasley et al.

(60) found that for acute trials and studies lasting a year, drug discontinuation attributed to weight gain was quite rare. For example, in a 6-week study, Tollefson et al.

(78) found that “none of 1,336 olanzapine-treated patients discontinued early because of weight gain.”

Given this background, it is important to consider methods for minimizing the impact of weight gain induced by antipsychotic drugs. One approach might be to implement weight control procedures with schizophrenic individuals who are taking antipsychotic medications. Several such efforts have been made in the past, including pharmacologic

(79,

80) and nonpharmacologic

(81–

85) approaches. In some cases, particularly with subjects in inpatient settings, results have been good. However, results with outpatients are less clear, and more research on this topic is needed. Some investigators have even begun to explore the potential of amantadine in pharmacologic treatment specifically for neuroleptic-induced weight gain

(86–

88), but this is not a generally accepted treatment at this time.

The use of pharmacologic treatments of obesity with this population may present challenges. With one exception

(89), all pharmacologic agents for the treatment of obesity that are currently available or likely to be released in the very near future achieve their effects by increasing noradrenergic, dopaminergic, and/or serotonergic activity

(90). In contrast, antipsychotic medications typically achieve much of their effect by decreasing dopaminergic and serotonergic activity. Therefore, the use of pharmacologic agents to treat obesity in individuals with schizophrenia may exacerbate their psychotic symptoms

(91–

95). Indeed, weight loss itself has even been reported to provoke psychotic symptoms in rare cases

(96). Therefore, any use of centrally acting pharmacologic agents to treat obesity in this population should be undertaken with the utmost caution and, in our opinion, be preceded by well-controlled clinical trials to establish efficacy and safety.

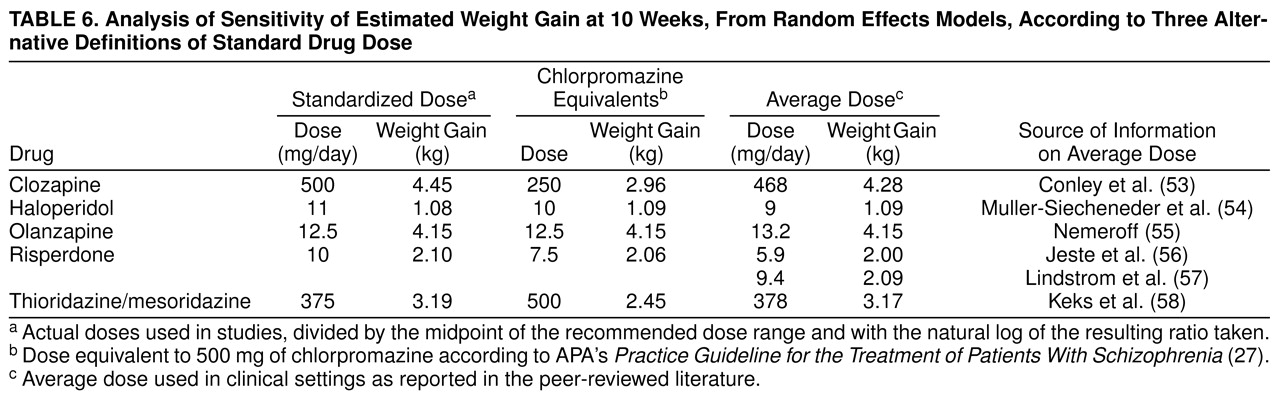

Finally, the selection of the right compound for the right patient might minimize the impact of weight gain with antipsychotic medications. There are schizophrenic individuals who are sufficiently thin that weight gain would likely be harmless and perhaps even beneficial

(8). In such cases, not all weight gain will necessarily represent fat. Studies also indicate that weight gain is highest in individuals with a low baseline body mass index

(60). Although these patients are rare, for such patients there would be little reason to avoid the use of drugs that produce greater degrees of weight gain. However, for patients with an average body mass index or higher or patients with a history of obesity, clinicians may wish to consider using compounds associated with less weight gain. The estimates provided in table 4 may help clinicians make such choices. The preceding notwithstanding, we wish to emphasize that weight gain should never be a sole reason for choosing one antipsychotic drug over another. Both therapeutic efficiency and other factors such as dose-related extrapyramidal syndromes should also be considered in drug selection. For many individuals the degree of risk imposed by the weight gain from a drug will not outweigh the degree of benefit achieved by alleviation of schizophrenic symptoms. In the end, clinical choices must be made on a case-by-case basis, with careful consideration of issues of weight, therapeutic efficacy, and other relevant factors.