Social phobia is a prevalent psychiatric disorder. If it is left untreated, its course is frequently chronic and characterized by impairment in social and occupational functioning. Of the medications studied for the treatment of social phobia, phenelzine

(1) and serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as paroxetine

(2) have demonstrated efficacy in controlled trials. The best-studied psychotherapy treatment for social phobia, cognitive behavioral group therapy, has demonstrated efficacy compared to both psychotherapy and a pill placebo

(3). However, about one-third of the patients treated do not respond to medication or cognitive behavioral group therapy. Alternative treatments are needed.

Interpersonal psychotherapy is a 12–16-week method that is described in manual form and is based on the premise that psychiatric disorders occur and are maintained within an interpersonal context

(4). Interpersonal psychotherapy focuses on improving the patient’s current interpersonal functioning as a means toward symptomatic recovery. Its efficacy in treating depression was demonstrated in controlled clinical trials

(5). Markowitz

(6) modified interpersonal psychotherapy for dysthymic disorder, with positive preliminary results. This suggests that interpersonal psychotherapy may ameliorate a syndrome of early onset and chronic course. The success of interpersonal psychotherapy for the treatment of eating disorders

(7) indicates that this treatment also has utility for nonmood disorders.

Social phobia’s prominent interpersonal features give interpersonal psychotherapy intuitive appeal as a treatment. Lipsitz and Markowitz (unpublished report) modified the interpersonal psychotherapy manual

(4) for social phobia, incorporating content and techniques relevant to this disorder. We then undertook an open clinical trial, while hypothesizing that interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia would improve symptoms and that improvements would approximate those obtained in established treatments.

METHOD

Participants were patients seeking treatment for social phobia at the New York State Psychiatric Institute Anxiety Disorders Clinic. After screening, an experienced clinician diagnosed social phobia by using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV

(8). Patients with current major depression, substance use disorder, and a history of psychotic symptoms were excluded, as were those currently in psychotherapy or taking medication for social phobia.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants after the study procedures were described in detail. Participants received 14 weeks of sessions in interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia from the therapist, a clinical psychologist (J.D.L.), who was first trained in standard interpersonal psychotherapy for depression. To ensure adherence to interpersonal psychotherapy standards, an experienced interpersonal psychotherapy supervisor (S.C.) reviewed videotapes of sessions of interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia and provided weekly feedback to the therapist.

Interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia followed the three phases of standard interpersonal psychotherapy

(4). Conceptual and technical aspects of this modification are described in detail in the treatment manual. In the initial phase (sessions 1–3), social phobia symptoms are assessed and identified as part of a treatable disorder. A primary interpersonal problem area is identified and agreed on as a focus. Of the four interpersonal problem areas in standard interpersonal psychotherapy

(4), role transition—negotiating a life change by adapting to new demands and giving up an old, familiar role—emerged as the most salient for social phobia. In the middle phase (sessions 4–11), the primary interpersonal problem area is addressed. In the termination phase (sessions 12–14), termination is explicitly discussed, progress is reviewed, and gains are consolidated.

Assessments were conducted at weeks 0, 7, and 14, comprising ratings given by independent evaluators and self-ratings. As independent evaluators assessed patients on other social phobia protocols in our clinic, we attempted to keep them blind to patient treatment. Both patients and the therapist made weekly assessments of symptomatic severity and improvement.

Clinician scales included the Clinical Global Impression (CGI) severity and change ratings from the Social Phobic Disorders Scale (1). With this measure, a 7-point Likert scale rates symptom severity from 1 (asymptomatic) to 7 (very severe). Ratings of change from baseline range from 1 (markedly improved) to 7 (markedly worse). The 24-item Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale

(1) generates four subscale ratings measuring fear and avoidance for performance and interactive situations. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression

(9) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety

(10) assessed associated symptoms.

Self-ratings included the self-rated CGI, the Social Anxiety and Distress Scale

(11), for measuring distress in social situations, and the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale

(11), for assessing cognitive expectations associated with social phobia.

Outcome was analyzed by using repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) with pairwise comparisons for dimensional measures. Given the small group size in this exploratory study, p values were uncorrected for multiple comparisons. Intent-to-treat analyses were conducted for weeks 0, 7, and 14, with the last observation carried forward for noncompleters. The response criterion was preset as CGI change ratings from independent evaluators of 1 or 2 (very much or much improved, respectively).

RESULTS

Nine participants with social phobia entered the trial. Seven met the DSM-IV criteria for generalized subtype on the basis of a clinical interview. All subjects completed the treatment, although one did not complete the week-14 assessment by an independent evaluator. The age range was 25–49 years (mean=38, SD=8). Five patients were men. Three were African American, three were Caucasian, two were Hispanic, and one was Middle-Eastern. All were college graduates. Six were employed. Two were married, and three were divorced.

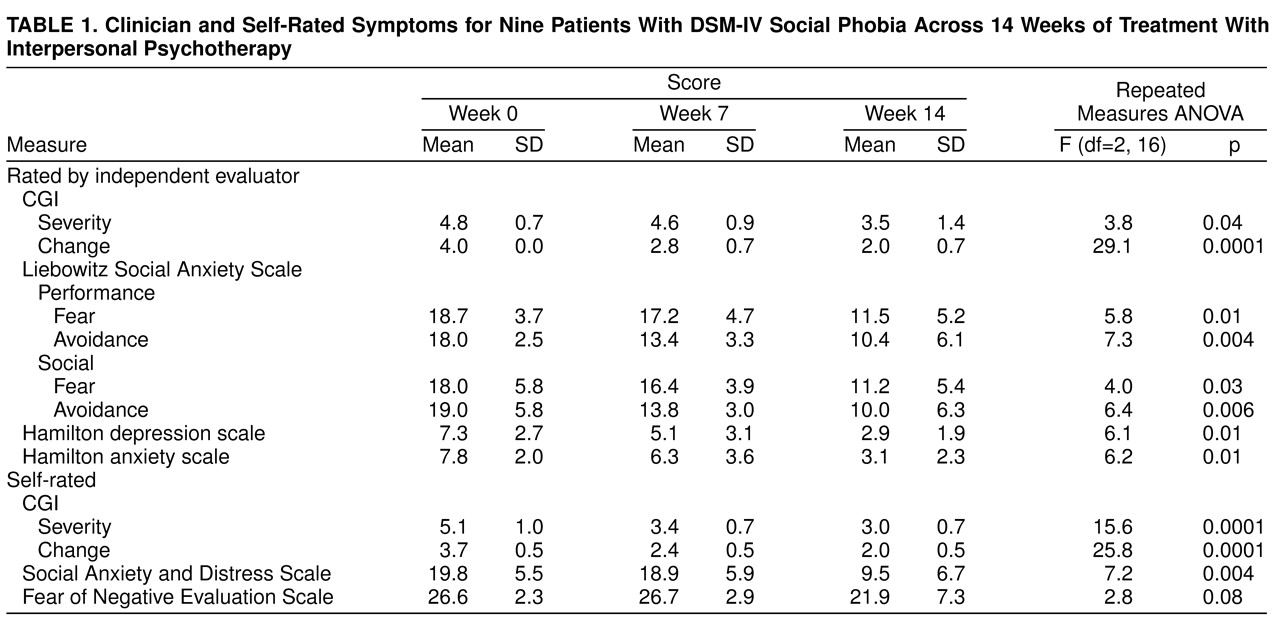

Table 1 shows independent evaluator and self-ratings at weeks 0, 7, and 14. Independent evaluator CGI severity ratings significantly improved by termination, when seven patients (78%) were rated as responders. Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale subscale ratings, which were assessed by an independent evaluator, showed significantly improved fear and avoidance in multiple domains. Hamilton depression and anxiety scale ratings significantly decreased, although baseline scores were low, and changes may lack clinical meaning.

Self-reported CGI severity ratings decreased significantly by termination, as did social distress ratings, as measured by the Social Anxiety and Distress Scale. The decrease in ratings for the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale was not significant. Therapist CGI severity ratings for weeks 0 (mean=4.4, SD=0.5), 7 (mean=3.4, SD=0.7), and 14 (mean=2.1, SD=0.6) also showed a significant decrease (F=31.7, df=2, 16, p<0.0001).

DISCUSSION

In this open trial, the first systematic study of interpersonal psychotherapy for an anxiety disorder, interpersonal psychotherapy appeared to be a promising treatment for social phobia. In post hoc comparisons, patterns and magnitudes of improvement approximated those of established treatments. Liebowitz and colleagues

(1) found that mean CGI ratings fell after 8 weeks of phenelzine treatment, from 4.8 to 3.3 (versus 4.8 to 3.5 for interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia) on clinician ratings and from 4.0 to 2.9 (versus 5.1 to 3.0 for interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia) by self-ratings. Patients in this study gave examples of qualitative life improvements, such as obtaining a new job, returning to school, and initiating dating, which suggested that changes were clinically meaningful. Although change ratings on the Fear of Negative Evaluation Scale did not reach significance in this small group, the magnitude of the change approximates that found with phenelzine treatment and cognitive behavioral group therapy.

Independent-evaluator-rated change was gradual and mostly occurred between weeks 7 and 14. Some patients initially confronted avoided social situations; this appeared to increase anxiety around mid-treatment, which patients sometimes experienced as setbacks. Thus, decreased avoidance preceded decreased fear on the Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale subscale ratings (

table 1). Interpersonal psychotherapy for the improvement of social phobia was slower than treatment with phenelzine

(1) but is comparable to the results obtained by means of cognitive behavioral group therapy

(3) and interpersonal psychotherapy for depression

(5). Hence, longer trials of interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia should be tested. Interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia was well tolerated, with no patient attrition.

This pilot study lacked a comparison group, and independent evaluators were not consistently blind to treatment status. Personal investment in interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia may have biased the therapist’s ratings. All patients were treated by a single therapist, and the small group size further limited the generalizability of the findings. Further study of interpersonal psychotherapy for social phobia in a larger clinical trial with a comparison group may address these limitations.