RESULTS

Reported Incidence of Childhood Sexual Abuse

Forty-six (17%) of the 269 patients reported experiencing childhood sexual abuse before the age of 16 years; 40 (87%) of these 46 patients were women. Because of the preponderance of childhood sexual abuse among women, we elected to study only women; therefore, our study group comprised the 40 women who reported childhood sexual abuse compared with the 131 women who did not report childhood sexual abuse.

The mean ages of the women who did or did not report childhood sexual abuse were 39.1 (SD=13.5, range=19–74) and 44.1 (SD=15.0, range=18–77), respectively (t=1.9, df=169, p=0.06); the trend for a between-group difference in age led us to control for current age in all analyses. The women who did or did not report childhood sexual abuse did not differ significantly on other sociodemographic variables examined, including mean number of years of education, employment, marital status, and whether they were currently involved in an intimate relationship. Of the 40 women who experienced childhood sexual abuse, five (13%) had been abused by a parent only, 28 (70%) had been abused by someone other than a parent, and seven (18%) had been abused by both a parent and someone other than a parent.

Lifetime and Current Depression and Anxiety

Few clinical features distinguished patients with and without a history of childhood sexual abuse. However, patients who reported childhood sexual abuse had made more visits to their psychiatrist in the previous 2 years (mean=26.8, SD=39.0, versus mean=15.1, SD=26.9) (F=4.10, df=1, p=0.04). In addition, more patients who reported childhood sexual abuse admitted to moderate or severe levels of hopelessness at interview (37 [93%] versus 97 [74%]) (χ2=4.90, df=1, p=0.02). The groups were comparable in percentages of self-reported helplessness, sinfulness, guilt, pessimism, worthlessness, and impaired self-image. More patients who were exposed to childhood sexual abuse than patients who were not reported significant feelings of self-annoyance or self-anger (34 [85%] versus 81 [62%]) (χ2=6.04, df=1, p=0.01), and more reported that they could lose control of their anger (19 [48%] versus 34 [26%]) (χ2=5.17, df=1, p=0.02).

There was a difference between groups in severity of depression as measured by self-report Beck depression scores: the patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse had a mean score of 33.7 (SD=9.5), compared with 26.9 (SD=11.4) for those who had not (F=12.65, df=1, p=0.001). There were no significant differences on other depression measures: clinician-rated Hamilton depression scores were 23.8 and 22.0, respectively, for patients who had and had not been exposed to childhood sexual abuse. The consultants’ rating of depression severity yielded similar scores for the two groups (mean=2.25 and mean=2.22, respectively), as did current Global Assessment of Functioning Scale scores (mean=47.2 and mean=50.1, respectively).

No differences in lifetime history measures were observed: patients who reported childhood sexual abuse had had their first episode of major depression at 25.4 years compared with 32.0 years for those with no childhood sexual abuse; the reported number of lifetime episodes of depression were 4.0 and 3.2, respectively; and duration of the current depressive episode was 35.2 and 30.4 weeks, respectively. The two groups of patients had similar rates of nonmelancholic depression according to the criteria of DSM-III-R (22 [55%] and 75 [57%]) and DSM-IV (23 [58%] versus 79 [60%]).

Lifetime prevalence of all anxiety disorders was similar for both groups: 50% of the patients in each group were given a diagnosis of any lifetime anxiety disorder. Social phobia was the most prevalent anxiety disorder for both of the groups: it occurred in 13 (33%) of the patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse and 33 (25%) of those who had not.

Parental Environment

Significantly more patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse reported having an alcoholic father than did those who had not (17 [43%] versus 26 [20%]) (χ2=6.77, df=1, p=0.01). No other differences in psychiatric family history were evident.

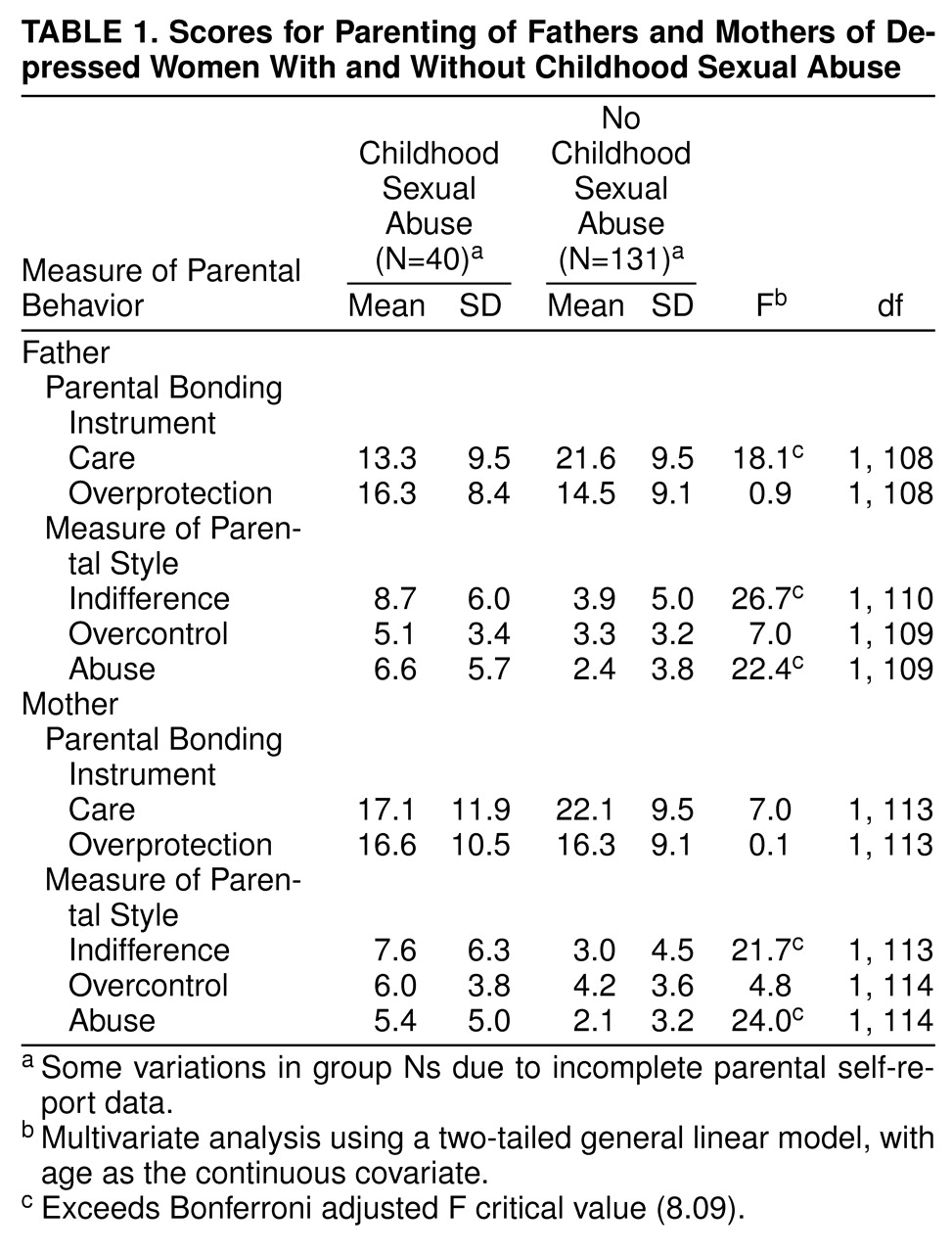

Table 1 presents the patients’ scores on the Parental Bonding Instrument and the Measure of Parental Style. Patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse had significantly lower care scores for fathers only on the Parental Bonding Instrument. These patients had significantly higher indifference and abuse scores for both parents on the Measure of Parental Style. There were no differences between the groups in Parental Bonding Instrument overprotection scores and Measure of Parental Style overcontrol scores for either parent.

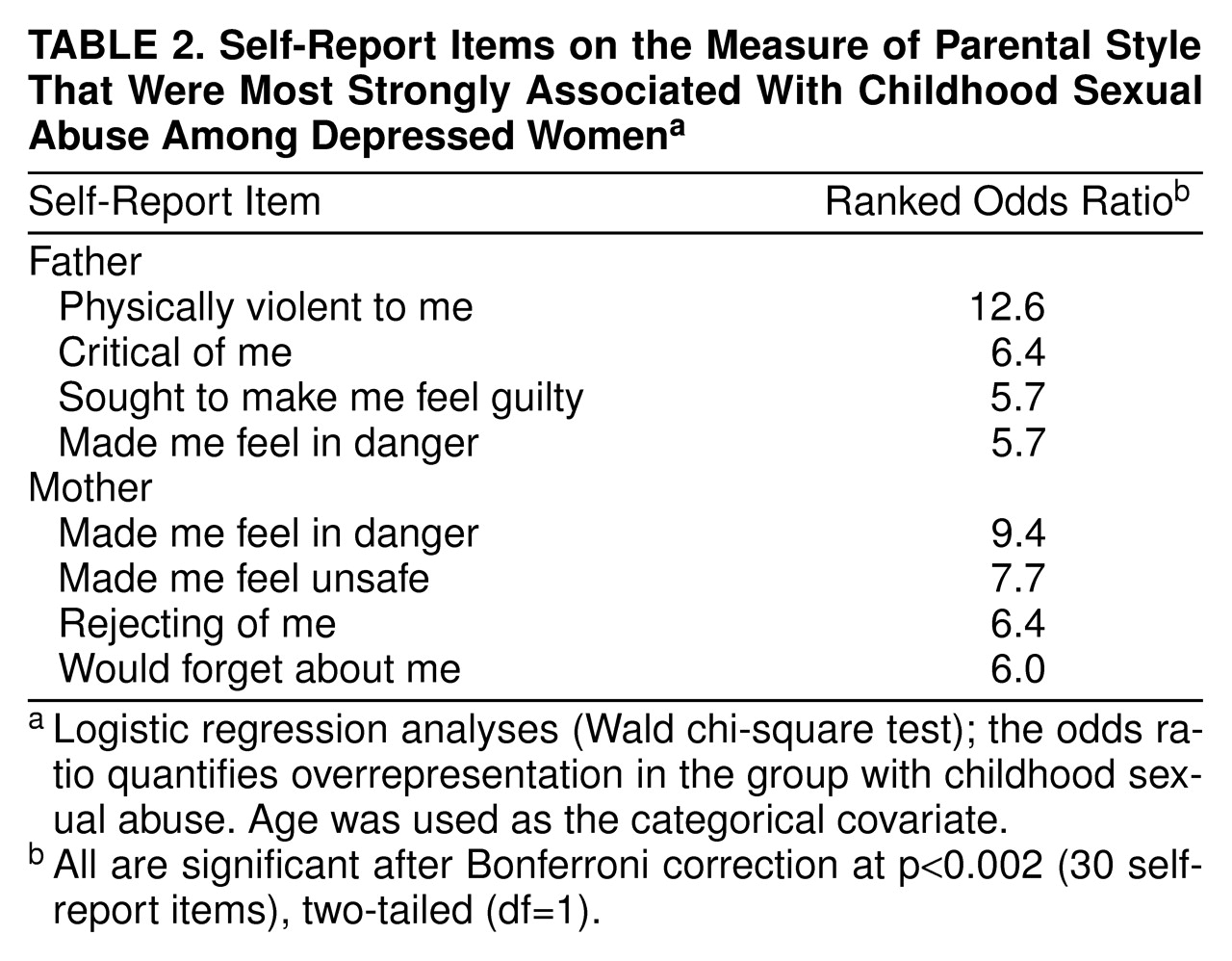

All Measure of Parental Style items were examined individually for group differences (patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse versus those who had not). Items with the four highest odds ratios (i.e., those items from the Measure of Parental Style most strongly associated with childhood sexual abuse) were ranked in descending order for fathers and mothers separately. Items of greatest distinction for fathers identified physical violence, criticism, making the child feel guilty, and making the child feel in danger. For mothers, distinctive items reflected lack of protection and maternal distance (

table 2).

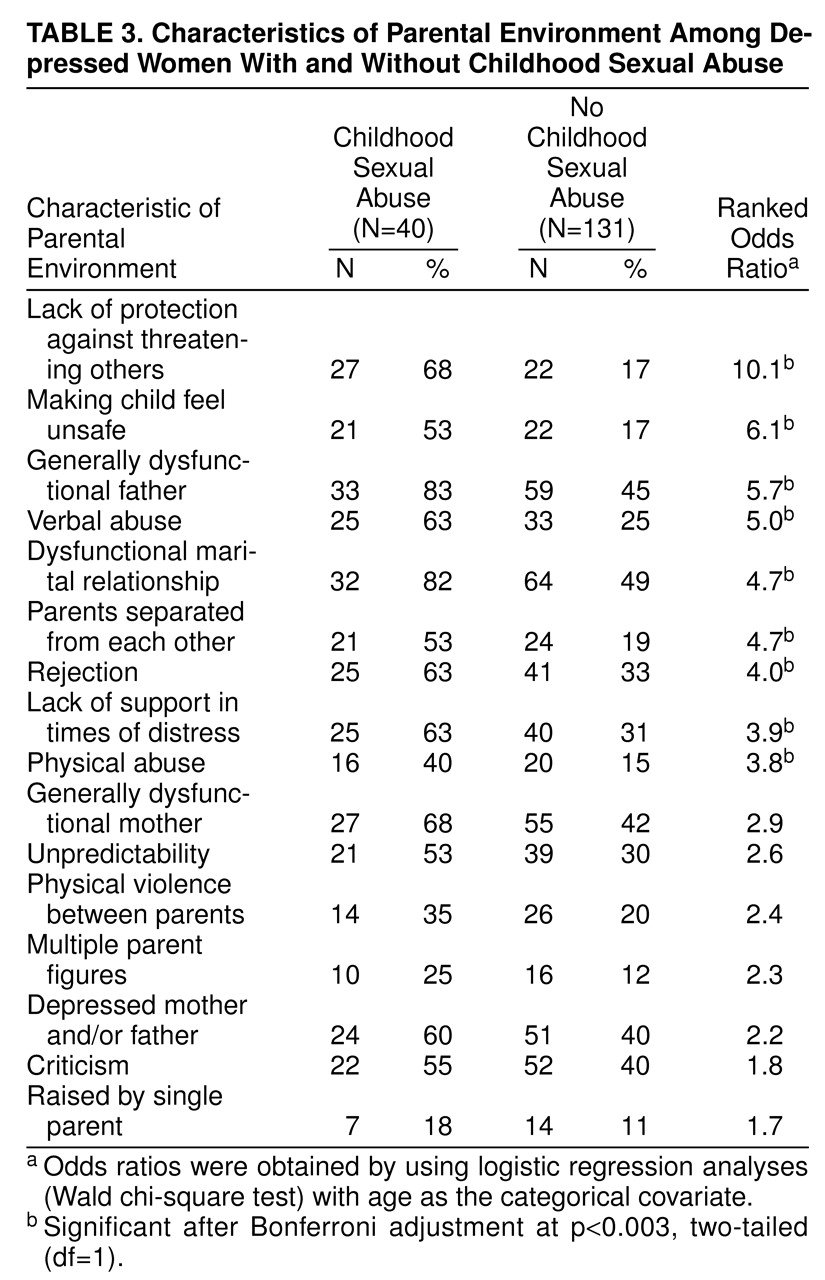

Table 3 lists the percentages of patients with and without exposure to childhood sexual abuse who reported certain parental environment characteristics during childhood. Lack of protection against threat posed by others was the most overrepresented experience affirmed by the childhood sexual abuse group. Other overrepresented characteristics were being made to feel unsafe, a dysfunctional father, verbal abuse, and exposure to an unstable relationship between parents. Hence, the general nature of the childhood environment (as measured by the Parental Bonding Instrument, the Measure of Parental Style, and interview-rated parental environment items) was able to distinguish patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse distinctly from those with no childhood sexual abuse.

Self-Injurious and Drug Use Behaviors

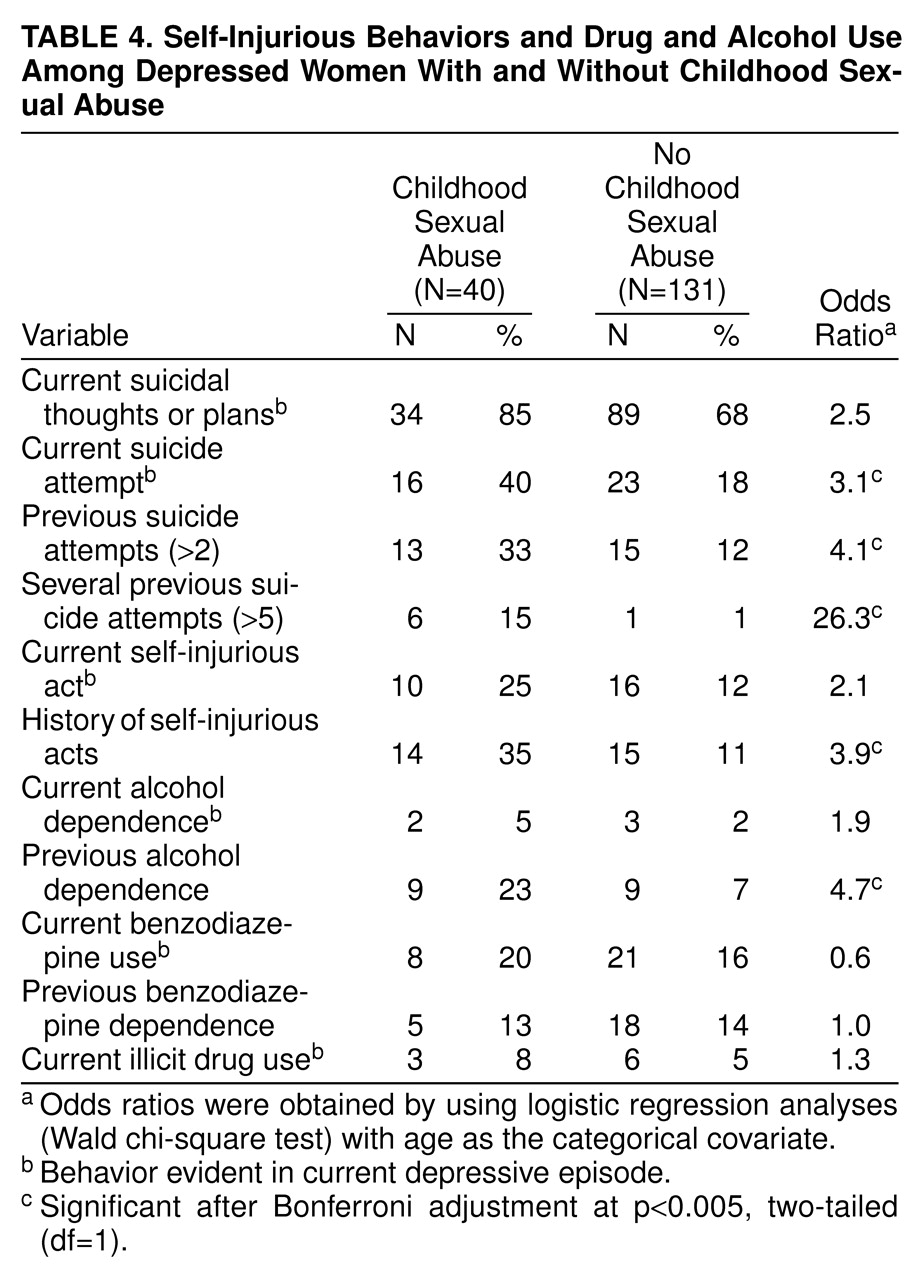

There were some notable differences in self-injurious behaviors between the two groups (

table 4). Significantly more patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse had made a suicide attempt during their current depression, and they had also made more previous suicide attempts. Significantly more patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse had a previous history of self-injury or self-mutilation, and more had been dependent on alcohol in the past. However, current alcohol dependence, past and present benzodiazepine use, and illicit drug use were similar across both groups. These results may have been affected by the fact that we excluded from the study patients with drug- or alcohol-induced depression.

Personality

More patients with exposure to childhood sexual abuse than patients with no exposure (26 [65%] versus 42 [32%]) were rated as having evidence of substantial personality disturbance before their current depressive episode (χ2=12.30, df=1, p=0.001). Similarly, patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse were significantly more likely to admit to a long-standing pattern of interpersonal sensitivity (27 [68%] versus 50 [38%]) (χ2=8.80, df=1, p=0.003).

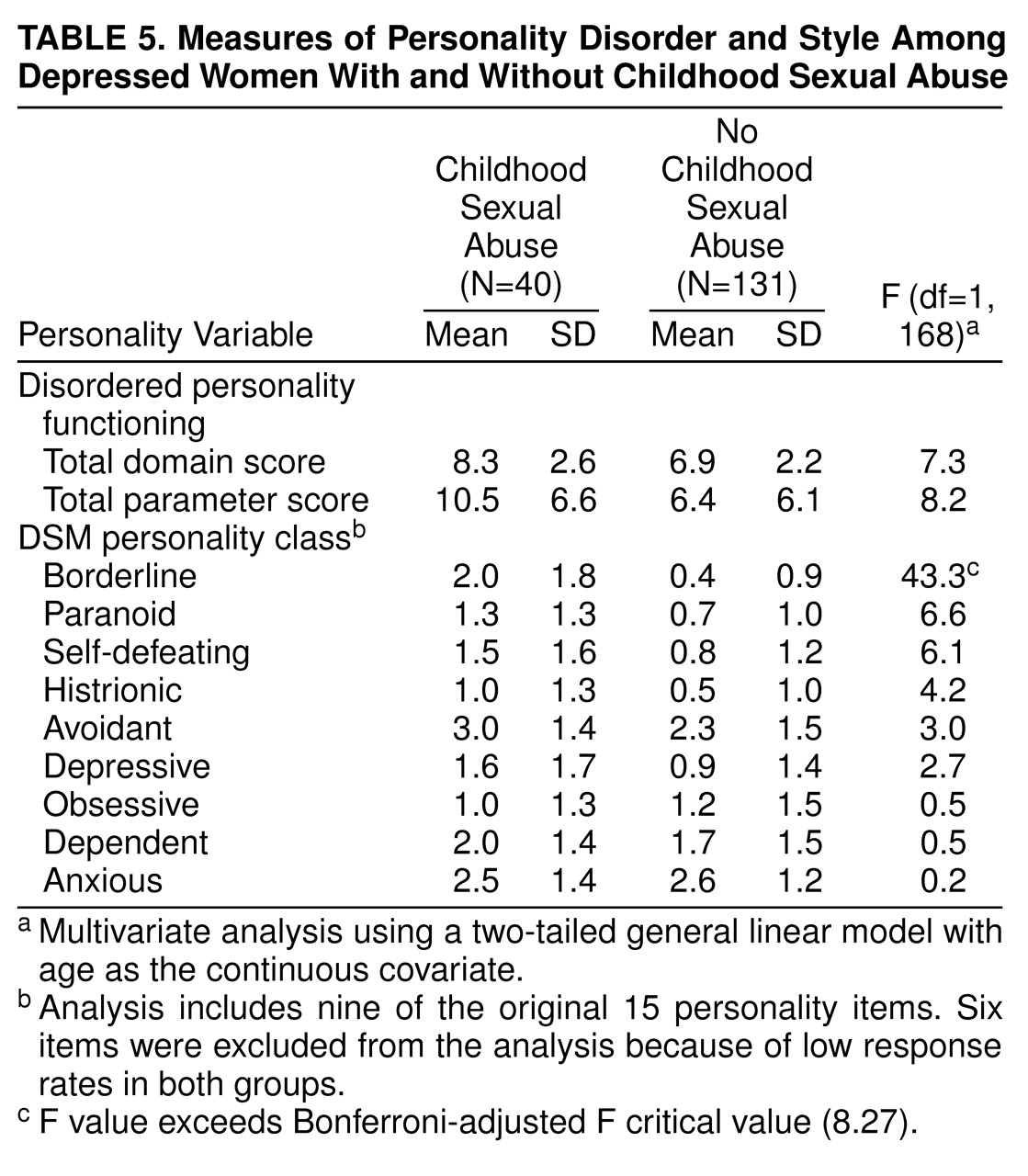

Table 5 examines the differences between the groups on a variety of measures of disordered personality function as well as styles underlying separate personality disorders. Nonsignificant trends were observed for higher domain and parameter dysfunction scores for the patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse. However, the only personality item score that was significantly higher for this group was the borderline descriptor.

Multivariate Analyses

Separate logistic regression analyses were used to identify any influence of the borderline personality style variable on the association between childhood sexual abuse and suicidal and self-injurious behaviors. Borderline scores, childhood sexual abuse status, and age (less than 35, 35–50, or more than 50 years) as a categorical covariate were entered into a logistic regression model with current suicide attempt as the dependent variable. The chi-square improvement statistics were 7.20 (df=1, p=0.01) for borderline; 1.37 (df=1, p=0.24) for childhood sexual abuse, and 0.37 (df=1, p=0.83) for age. These results indicate that higher scores on the borderline item were significantly associated with a greater likelihood of there having been a suicide attempt during the current episode. Being in the childhood sexual abuse group did not add further predictive value to the chance of making a current attempt. This analysis was repeated with several suicide attempts (more than five) as the dependent variable. Again the analysis indicated that the borderline descriptor was a dominant predictor of having made more than five previous attempts at suicide (χ2=7.43, df=1, p=0.006) and that the childhood sexual abuse variable (χ2=1.04, df=1, p=0.31) and age (χ2=2.82, df=1, p=0.24) did not add any predictive value beyond that of the borderline descriptor for the existing relationship between childhood sexual abuse and previous suicide attempts.

A further analysis that used previous self-injury as the dependent variable yielded the same result. Borderline scores (χ2=26.37, df=1, p<0.001) rather than childhood sexual abuse status (χ2=0.26, df=1, p=0.69) were associated with the increased likelihood of a history of self-injury.

Thus, the borderline descriptor stood out as a significant mediating influence of self-harmful behaviors in that it appeared to account for the connection between childhood sexual abuse and self-harm. Because of its obvious significance, the borderline variable was examined against other rated parental characteristics. First, all parental environment predictors were correlated with borderline scores to assess whether any overlap existed. Modest but significant relationships were observed between borderline scores and paternal care (r=–0.34, p<0.01), maternal indifference (r=0.40, p<0.01), maternal abuse (r=0.30, p<0.01), paternal indifference (r=0.37, p<0.01), paternal care (r=–0.29, p<0.01), and childhood sexual abuse status (r=0.48, p<0.01). Although some overlap did exist, interpretations concerning the independent role or effect of each predictor variable could not be made because correlation coefficients were not high.

A linear regression analysis examined components of the parental environment (care scores on the Parental Bonding Instrument, indifference and abuse scores on the Measure of Parental Style, childhood sexual abuse status) associated with higher borderline scores. The regression model indicated that having a history of childhood sexual abuse was the only significant variable (t=4.66, df=7, 94, p<0.001) and that the other measures of parental environment were nonpredictive. This result indicates that childhood sexual abuse status contributed to higher borderline scores irrespective of other aberrant characteristics of the parental environment.

Similar analyses were conducted for current suicide attempt, previous attempts, and history of self-injury, with the aim of isolating any independent effects of childhood sexual abuse above and beyond other aberrant parental characteristics on these adult self-harm behaviors. For current suicide attempt, the only characteristic of the early environment that was a significant predictor was childhood sexual abuse status (χ2=4.12, df=1, p=0.04). For several previous suicide attempts, significant predictors were higher maternal indifference scores on the Measure of Parental Style (χ2=4.41, df=1, p=0.03) and having a history of childhood sexual abuse (χ2=4.44, df=1, p=0.03). For history of self-injury, childhood sexual abuse alone and independent of other characteristics had significant predictive value (χ2=4.39, df=1, p=0.03). Thus, for current suicide attempt and history of self-injury, childhood sexual abuse was the dominant predictive characteristic of the early environment, whereas for several previous suicide attempts, high maternal indifference scores and childhood sexual abuse were equally predictive characteristics.

DISCUSSION

Childhood sexual abuse has long been held to have a number of short-term and long-term consequences, including depression in adulthood. Having been sexually abused in childhood may increase the likelihood of depression or may influence the expression and severity of depression, either directly or indirectly, as a consequence of a more general aversive early environment. We studied a group of female patients with primary major depression, focusing on identifying nuances of the parental environment for those reporting childhood sexual abuse and then considering any role that childhood sexual abuse might bring to adult depression. Our study relied to a large degree on self-report data, a method that risks a range of retrospective biases, particularly in view of the fact that patients with a borderline personality style are recognized as tending to blame others. Thus, while we explore causal links, such noncausal possibilities must be conceded.

We found no sociodemographic differences between the patients who did or did not report childhood sexual abuse. Depressive features did not distinguish these two groups of patients, but patient-rated Beck depression scores were significantly higher for those who reported childhood sexual abuse. However, psychiatrist-rated estimates of the severity of depression did not differentiate the two groups. Nor was there any difference in the incidence of lifetime anxiety disorders. We found that patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse reported significantly more adverse childhood environment experiences and that multiple types of parental dysfunction were indicated. Patients who were exposed to childhood sexual abuse also differed in reporting higher self-injury and suicide attempt rates and in having more disordered personality functioning.

The latter differences, together with the fact that patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse reported more psychiatric visits and had higher self-report scores on hopelessness, self-disapproval, and the Beck inventory, may be consequences of childhood sexual abuse or may be explained by differences accounted for by overrepresentation of an identified personality disturbance (i.e., borderline style). Therefore, in this study group, childhood sexual abuse could not be clearly linked to greater severity of depressive symptoms per se but was significantly linked to antecedent environmental factors and long-standing patterns of dysfunctional behaviors.

It has been argued extensively that anomalous childhood environments can play a causal antecedent role in the development of depressive disorders. Even though most of our patients with exposure to childhood sexual abuse had been abused by someone other than a parent, they also reported a more detrimental parental environment than did depressed patients with no history of childhood sexual abuse. Although no more likely to have a family history of mental illness, patients who had been exposed to childhood sexual abuse were more likely to have grown up with an alcoholic father, a finding that has been reported by others

(24). Alcohol dependence, being raised by an alcoholic parent, early life stressors, and chronic psychosocial turbulence, including dissatisfaction and self-destructiveness, have also been linked to characterological depressions

(25,

26).

Our patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse recalled a family environment characterized by low levels of parental care (particularly from fathers) as well as high levels of parental indifference and abuse. Similar themes, particularly that of low levels of care, have been reported in previous studies

(2,

5), some of which also used the Parental Bonding Instrument

(14,

27). Both of the latter studies, however, found an association between childhood sexual abuse and high levels of parental overprotection, whereas the present study found no evidence for higher Parental Bonding Instrument overprotection scores for either parent. In contrast, lack of protection against threat posed by others was the most commonly reported parental environment characteristic associated with childhood sexual abuse (

table 3), which is consistent with our finding that 70% of our patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse were abused by someone other than a parent. The items in table 3 identified the childhood sexual abuse environment typically as nonprotective and nonsupportive, with conflict, violence, and marital turbulence.

Key Measure of Parental Style items for fathers portrayed a paternal relationship characterized by more general abuse and threat; for mothers, dominant items suggested a relationship characterized by lack of protection, feeling in danger, and maternal disconnectedness. Therefore, these patients, in addition to reporting sexual abuse, also recalled more severe degrees of other parental dysfunction and provided evidence of greater parental marital problems.

Our multivariate analyses allowed us to speculate on the contribution and sequential associations of aberrant parental environment, adult self-injury, and personality dysfunction for the patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse. The question as to whether childhood sexual abuse may be pathogenic in any unique form or is pathogenic as part of a childhood environment with ubiquitous adversity has received attention in recent years.

For our study group, childhood sexual abuse appeared an equally predictive factor, along with high maternal indifference, of making multiple suicide attempts in adulthood, a finding highlighted in previous studies

(14,

27–29). However, childhood sexual abuse was identified as a single predictor of self-destructiveness in the form of past self-injury and a current suicide attempt. In relation to personality, we found that the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and adult behaviors of self-harm (history of self-injury, several past suicide attempts, and current suicide attempt) was determined more by the influence of higher borderline descriptor scores. Thus, borderline disorder might act as a mediating factor enabling a pattern of long-standing self-destructiveness.

Figueroa et al.

(30) argued that interpersonal sensitivity may act as a temperamental substrate with which sexual abuse experiences interact to effect a borderline diagnosis. For our study group, a pattern of long-standing interpersonal sensitivity was affirmed for significantly more patients with a history of childhood sexual abuse than patients with no childhood sexual abuse (68% versus 38%), a finding that provides further support for this view.

After identifying the apparently significant role of borderline personality, we aimed to track its possible evolution for our depressed group. When childhood sexual abuse was considered in conjunction with other negative aspects of the childhood environment, we found that childhood sexual abuse status was a better predictor of higher borderline personality style scores than other parental environment characteristics. Therefore, we speculate that childhood sexual abuse may well act to effect a borderline personality style as a dominant antecedent, not just as an equally negative component within a dysfunctional family style. Thus, although borderline characteristics appeared to engulf the association between childhood sexual abuse and self-harm, they could, in fact, be traced to a history of childhood sexual abuse. Even though such speculations risk circularity, we were able to disentangle some close associations for our study group, namely, that childhood sexual abuse contributed most strongly (and possibly independently) to higher borderline scores but not exclusively to some expressions of self-harm.

Even though childhood sexual abuse status had strong links to self-destructive behavior (alone or with a pattern of maternal indifference), and was a likely causative and dominant factor in the expression of borderline features, it was also closely associated with an otherwise adverse early environment. Thus, a history of childhood sexual abuse appears associated with a greater chance of exposure to earlier dysfunctional family factors, which, in turn, are associated with a greater risk of depression, disordered personality function, and other psychopathology.